Canadian troops encounter the remains of a Chinese soldier (opposite) on the perimeter of their position near the 38th parallel dividing the Koreas. The piece is entitled “Welcome Party.”[ed Zuber/CWM/19890328-004]

As a teen soldier fighting in the Korean War, Ted Zuber wanted to be a sniper. He also happened to be a painter and, therefore, something of an individual and a loner. The autonomy of sniper work attracted him. But the jobs were all filled.

The Chinese People’s Volunteer Army changed all that in November 1951, wiping out his battalion’s entire sniper unit with artillery strikes during the notorious fighting at Hill 355. And so, Zuber became a sniper.

Two months later, the Montreal native was peering through a rifle scope at an enemy position just a few hundred metres away in the snow-covered hills near the 38th parallel dividing the Koreas, when a pair of Chinese soldiers appeared.

Zuber fired twice, dropping both men, one after the other.

Shortly after, a third Chinese soldier cautiously rose from the trench waving a white flag. Zuber eased off on the trigger while two others appeared and fetched one of the casualties before returning to cover.

The flag man “must have been terrified because he’s been told to go out there and expose himself to that Canadian sniper and wave the flag hoping I will obey it,” Zuber told the Canadian War Museum a few months before he died in 2018.

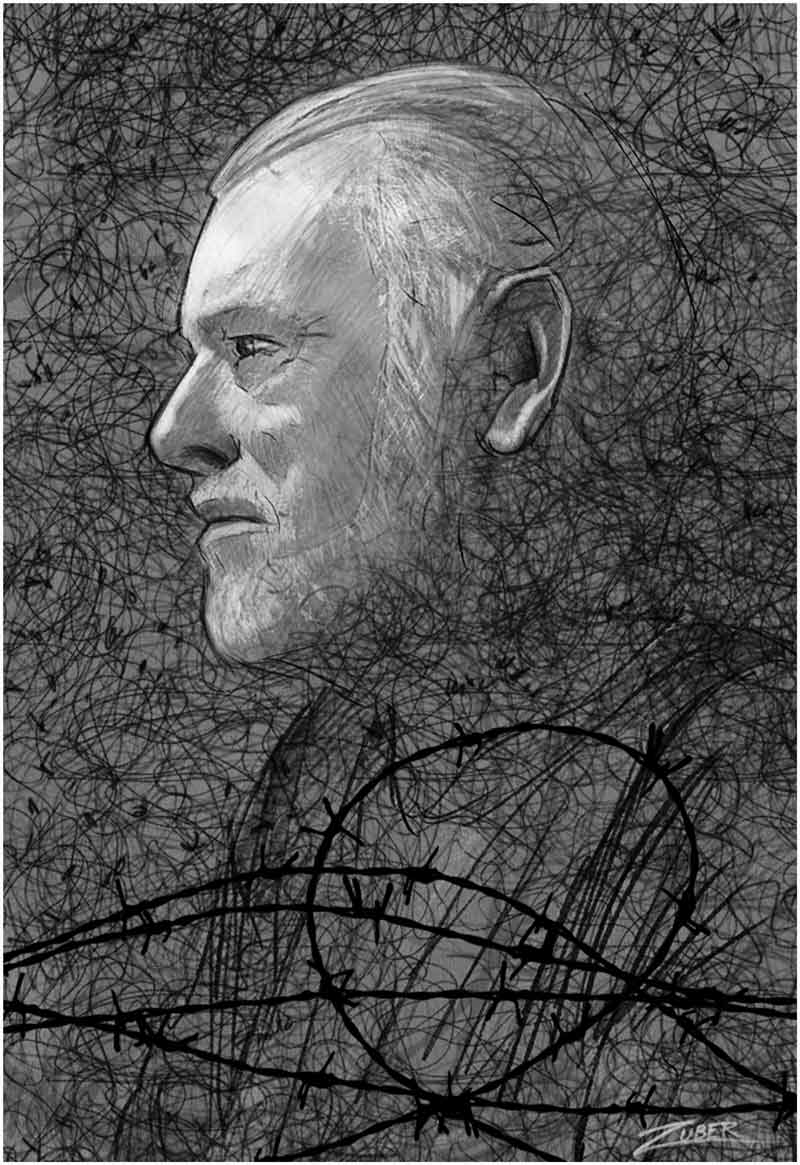

“The portrait is derived from an original song my father wrote about his exploits as a soldier in Korea,” said Ted’s son Tom. The song describes the daily chore of replacing barbed wire destroyed by Chinese artillery.[Courtesy Tom Zuber/Zuber family]

“I had a chance, for a few moments, to be an honourable—I’m going to cry—to be an honourable human being. And I never would have shot any of these people under a white flag, ever.”

Zuber was an artist—an illustrator—and, while he performed the surgical task of cold killer on the Korean peninsula, he did so with an artist’s sensibility. Some soldiers kept journals, wrote letters or fashioned trench art from the detritus of war. In the quiet moments, Zuber would sketch.

That artist’s sensibility would cost him later as he struggled with what we now know as post-traumatic stress disorder. He eventually resorted to his art to deal with his demons, digging out the old sketches and creating vivid illustrations of what he saw and experienced during the 1950-53 war.

The war museum has 182 prints, drawings and paintings by Zuber in its massive Beaverbrook Collection of war art, including 15 paintings and 20 drawings he did based on his time in Korea.

“I never would have shot any of these people under a white flag, ever.”

A U.S. navy Corsair breaks the morning stillness in Zuber’s “Land of the Morning Calm”[Ted Zuber/CWM/19890328-005]

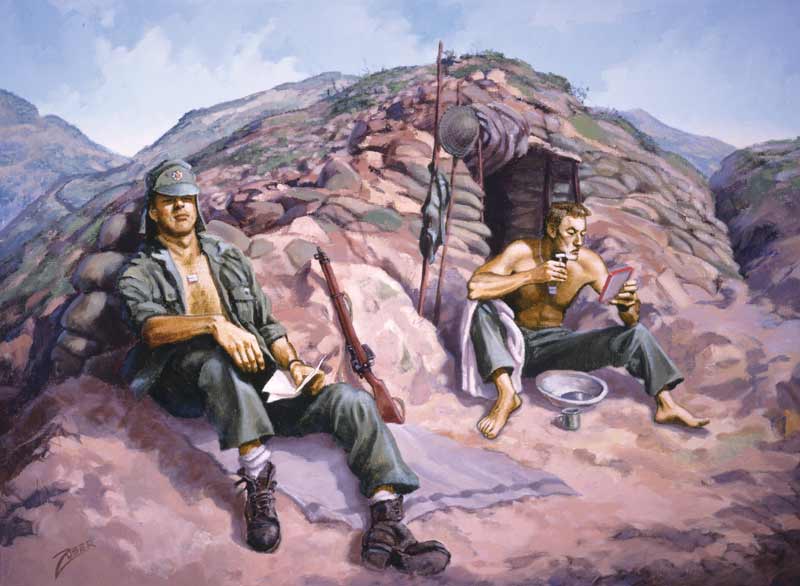

In “Reverse Slope”, Zuber depicts the daytime disposition typically adopted by Canadian troops along the Jamestown Line. They would withdraw from front-line trenches to rest before returning to the action at night. [Ted Zuber/CWM/19860158-003]

In “First Kill—The Hook,” Zuber shows a sniper and his scout at work in January 1953.[Ted Zuber/CWM/19890328-003]

A Tribal-class destroyer (top) does its work along the North Korean coast in the painting “Daybreak.”[Ted Zuber/CWM/19890328-013]

Soldiers of ‘B’ Company, The Royal Canadian Regiment, react to an artillery attack on Oct. 23, 1952, in “Incoming”. The 45-minute bombardment was among the heaviest Canadians endured in Korea. [Ted Zuber/CWM/19890328-008]

U.S. air force planes drop supplies at Kapyong, where 1,500 Canadian and Australian troops turned back 10,000-20,000 Chinese soldiers in April 1951. [Ted Zuber/CWM/19900084-001]

Zuber fired twice, dropping both men, one after the other.

An infantryman keeps watch in “Silent Night”.[Ted Zuber/CWM/19890328-009]

He eventually resorted to his art to deal with his demons.

“The Hunters” captures a sniper in the golden hour. “I wonder who those guys were that I killed,” Zuber said in 1999. “I just remind myself, ‘hey Ted, you know what the hell it was all about.’” [Ted Zuber/CWM/19890152-001]

In Zuber’s painting “The Bowling Alley” (right), a machine-gun crew peers out over the valley for which it was named, where UN forces defeated the opposition in early fighting.[Ted Zuber/CWM/19890328-002]

Advertisement