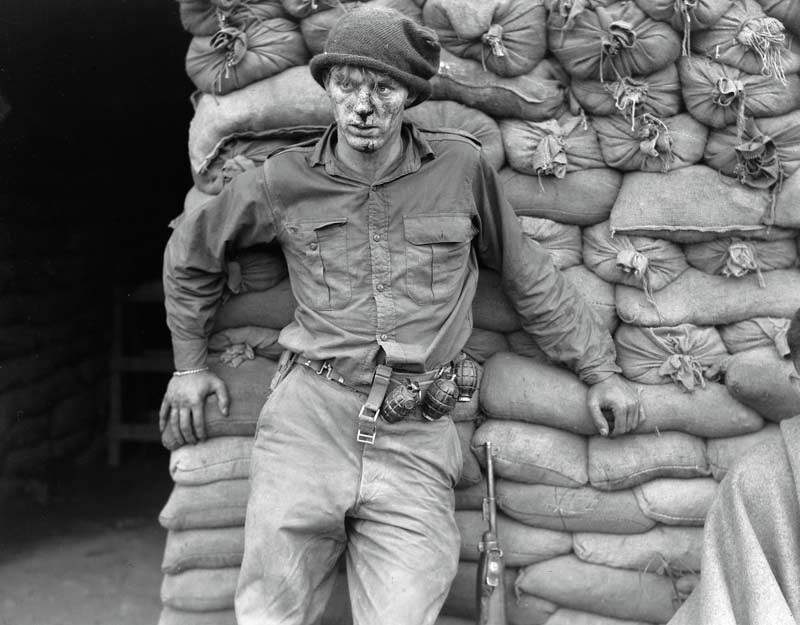

[Paul E. Tomelin/LAC/3397530]

Paul E. Tomelin’s photograph of a young Canadian private awaiting medical aid after battle stands among the Korean War’s most compelling images, and one of the best war photographs a Canadian has ever taken.

A sergeant in the Canadian Army Film and Photo Unit, Tomelin (above) was deployed to the Korean peninsula for one year in 1951-52. He managed to wrangle another six months in-country, during which he said he did some of his best work.

[LAC/3534217]

None was better than his June 22, 1952, photograph (left) of a bloodied and battered Private Heath Matthews of Charlie Company, 1st Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment, wounded by shrapnel and looking older than his 19 years.

Matthews, a signaller, was standing outside a medical tent awaiting his turn with the medical officer after a company-strength raid the night before on an enemy position near Hill 166, the dominant feature on the Chinese side of the Nabu-ri Valley. Canadian units suffered some 131 casualties in the area that May and June, including two killed and several wounded during the Charlie Company raid.

“I noticed a soldier leaning up against the [sandbags outside the] hilltop regimental aid post,” Tomelin recalled in an interview for a unit history three years before he died in 2016. “I wanted to get a photograph of him earlier, but I would have had to do it with a flash and I felt that wouldn’t reproduce the images as well as natural light, so I kept an eye on this soldier as he moved in the lineup.

“He was less injured than many of the others and he was getting close to the entrance. It was getting to be around four o’clock in the morning and daylight and he happened to be at the back entrance to the regimental aid post and I realized that if I didn’t get it now I wouldn’t get it.

“So, I raised my camera to take his photograph and he pushed himself away with disgust that he didn’t want his photograph taken. He was going to leave so I raised both my hands and I said, ‘Please just go back the way you were.’

Known as “The Face of War,” it became an icon in the annals of Canadian photojournalism.

“It took no persuasion, he dropped right back against the sandbags and asked, ‘Where do you want me to look?’ I just raised my arms and more or less pointed over my left shoulder the direction in which he was looking generally and got him looking over my shoulder and I raised the camera again, focused and took the photograph.”

Known as “The Face of War,” it became Tomelin’s signature picture and an icon in the annals of Canadian photojournalism.

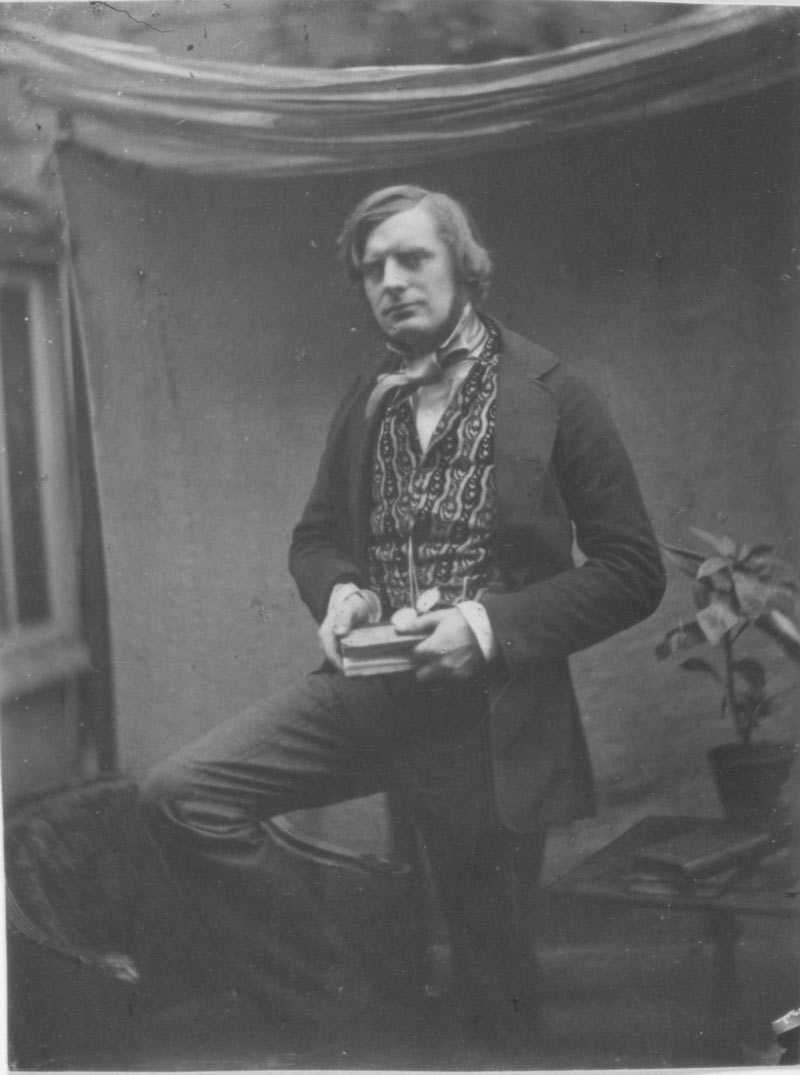

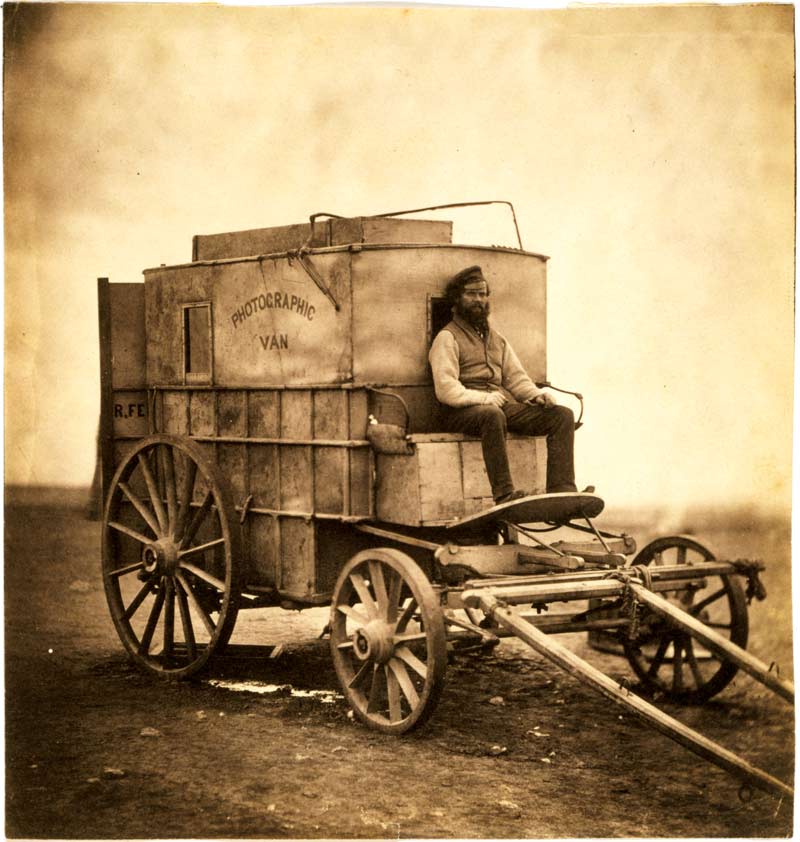

Roger Fenton[Roger Fenton/MetMuseum/2005.100.285]

Iconic Canadian war photographs are relatively few and far between, especially compared to the archive of American and British images chronicling conflicts as far back as the Mexican-American War of the 1840s, from which 12 daguerreotypes made by an American photographer, his name lost to history, survive.

Stored in a walnut case, the images depict U.S. army troops, a general and his staff, Lieutenant Abner Doubleday—he of Cooperstown baseball fame—along with military units and scenes around the Mexican town of Saltillo, then-occupied by U.S. forces. They are the earliest known photographs of war.

More famously, Briton Roger Fenton documented the Crimean War of the 1850s, during which he took his picture “Valley of the Shadow of Death,” a cannonball-strewn road near Sevastopol. There were actually two pictures, one with cannonballs on the road and one without—graphic evidence that photojournalistic standards were still in their infancy.

“Valley of the Shadow of Death”, replete with cannonballs, in Crimea[Victoria and Albert Museum/U.S. Library of Congress]

“Valley of the Shadow of Death”, replete with cannonballs, in Crimea [A World History of Photography/The Science Museum]

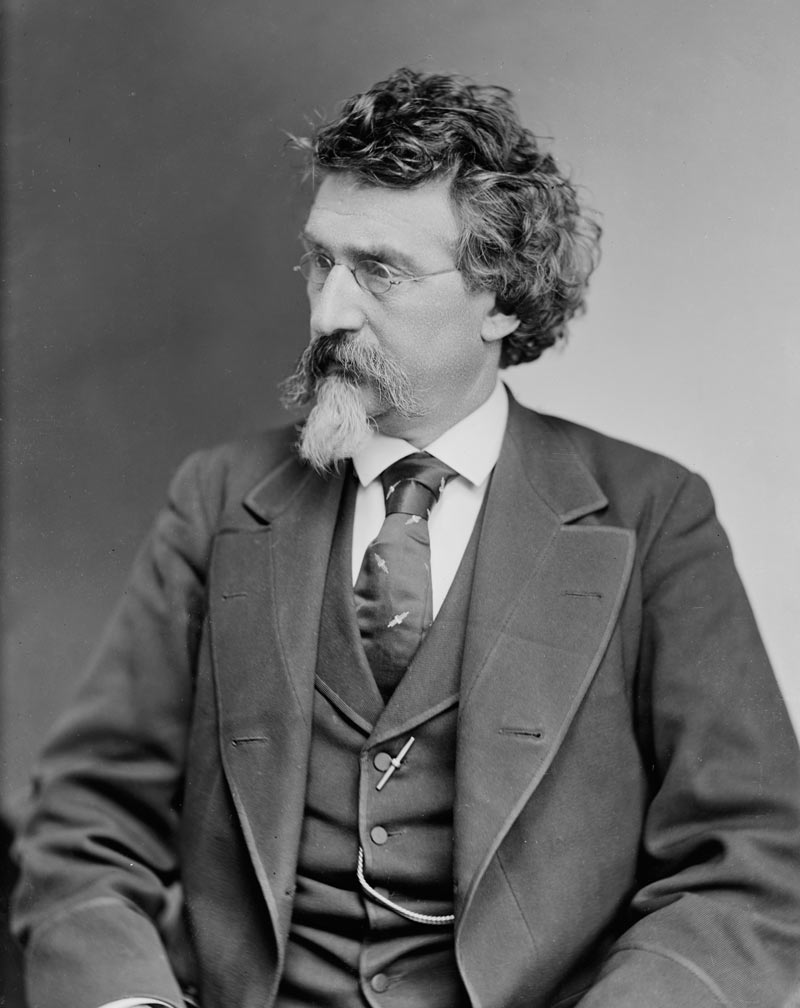

And perhaps most famously, New Yorker Mathew Brady blazed a trail in America with his photographs of U.S. Civil War battlefields littered with dead soldiers. In fact, many of the thousands of images credited to Brady were taken by assistants—he had more than 20, several of whom were not above arranging the dead for the sake of a good photograph.

Canada hasn’t been in as many wars as the U.S and Britain and, when it has, its photographers have often faced restrictions.

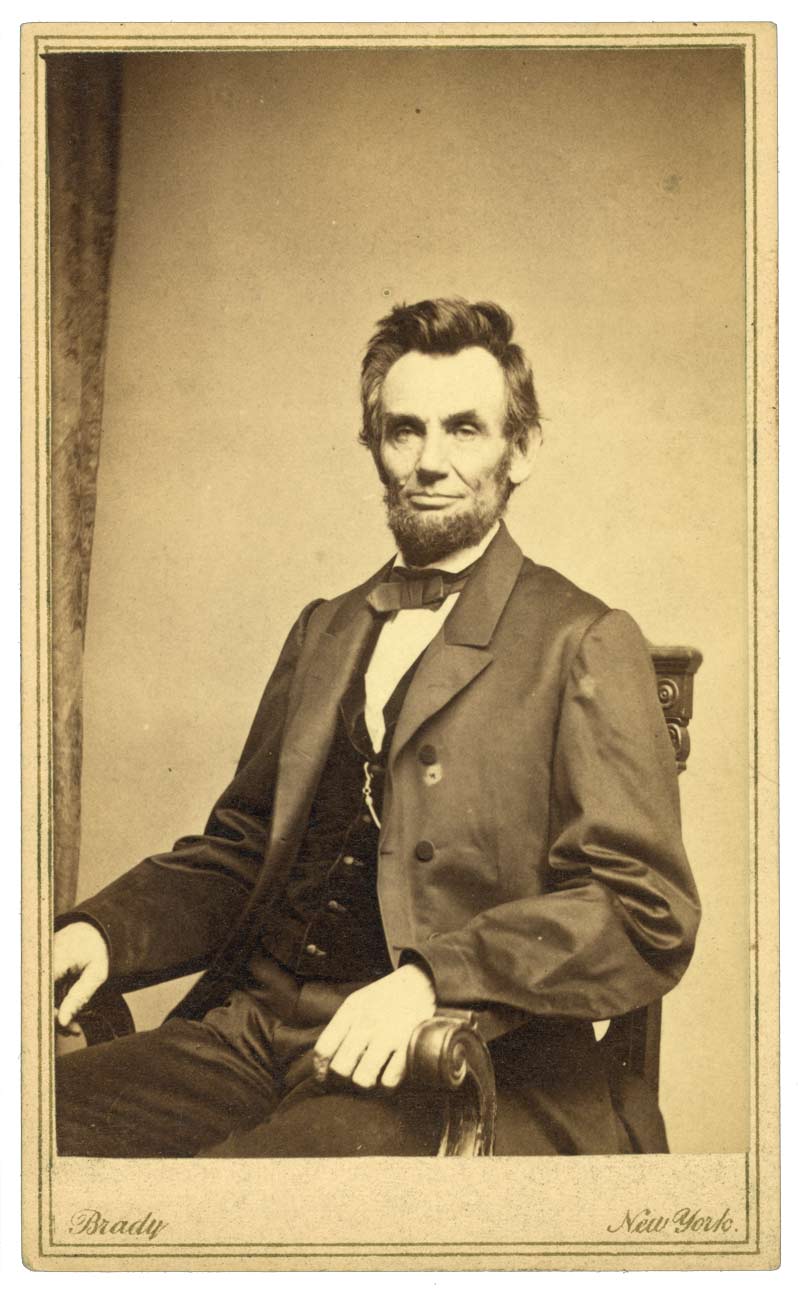

Brady’s serene portraits of a progressively aging Abraham Lincoln document the toll the four-year war took on the man many consider the country’s greatest president.

Canada hasn’t been in as many wars as the U.S. and Britain and, when it has, its photographers have often faced restrictions foreign to their counterparts.

Mathew Brady contracted out much of his U.S. Civil War work. [Brady-Handy Photograph Collection/U.S. Library of Congress]

The picture of Confederate dead at Fredericksburg, Va., is often credited to Brady, but was actually taken by Andrew J. Russell.[Mathew Brady/National Archives at College Park/U.S. National Archives/1135962]

Brady’s 1864 portrait of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln.[Andrew J. Russell/Mathew Brady/U.S. Library of Congress/2008680391]

Fenton’s wagon carried the photographer’s tools of the day.[Roger Fenton/U.S. Library of Congress/cph.3g09240]

The country’s foray into war photography began with the First World War, and it was handicapped from the outset.

Canadian operations fell under British command and British commanders were resistant to battlefield photography over concerns that images might provide the enemy with potentially valuable information. Soldiers were forbidden to take photographs, though some did.

Only three “official” photographers, all born in England and all in uniform, were authorized to photograph Canada’s role in the war: Captain Henry Edward Knobel, Captain William Ivor Castle and Lieutenant William Rider Rider—each an experienced photojournalist.

According to the Canadian War Museum, authorities in Ottawa recognized the value in a photographic record of the country’s war effort overseas. In January 1916, newspaper baron Max Aitken, later known as Lord Beaverbrook, received government authorization to establish the Canadian War Records Office. Its mandate: document the war through photographs, artwork and motion pictures.

Some 80 years before Photoshop, Australian Frank Hurley made masterpieces out of multiple images. “A Raid” combined 12 negatives and, printed in two parts, it measured 6.1 by 4.7 metres.[Australian War Memorial/P05785.001]

Some 80 years before Photoshop, Australian Frank Hurley made masterpieces out of multiple images. “A Raid” combined 12 negatives and, printed in two parts, it measured 6.1 by 4.7 metres.[Frank Hurley/State Library of New South Wales]

Photography at the time was still a rudimentary exercise involving bulky equipment, primitive technology, limited capabilities and formidable obstacles—not the least of which was getting large cameras, tripods, film plates and, often, highly toxic chemicals to the front and back.

An image from October 1917 shows Rider, his driver and an assistant making their way through a trench near Lens, France, carrying a tripod and two oversized boxes—a far cry from the 35mm cameras that would come to revolutionize the craft.

“A good many people believe that taking pictures at the front is ‘cushy,’” Rider wrote for Canada in Khaki, a short-lived magazine that chronicled the country’s role in the Great War. “I believed so myself—until I tried it, and became suddenly bereft of the illusion.”

Capturing the movement and complexity of battlefield action was all but impossible. As a result, many First World War photographs are static, staged or are composites assembled from multiple images.

Australian Frank Hurley, who famously photographed Ernest Shackleton’s doomed Antarctic expedition in 1914-16, was the acknowledged master of the composite photograph, creating stunning battlefield panoramas that could take up entire walls. His masterpiece, “A Raid,” was made up of 12 negatives and printed in two parts. First shown at Grafton Galleries in London in 1918, it measured 6.1 by 4.7 metres.

Size seemed to matter when it came to early war photographs. Billed as “the biggest photo of the First World War,” Castle’s stunning composite “The Taking of Vimy Ridge” was first exhibited with other Canadian war photographs in London in 1917. At 6.1 by 3.35 metres, however, it was not as big as Hurley’s. A phenomenon in its time regardless, the piece was printed in five sections and took five hours to frame. It depicts the scene on the first day of the iconic battle that is said to have marked the birth of the nation: April 9, 1917.

Composite, manipulated and staged photographs were at issue for much of the war, with Castle and British army Second Lieutenant Ernest Brooks accused of faking images.

Indeed, Castle’s photograph “Over the Top,” initially believed to have been taken at the front in October 1916, was proven to have been a composite of rehearsals and shell bursts at a trench-mortar school near Saint Pol, France.

Ethics in photojournalism have been debated since its inception and, just as they were a hot-button issue with the onset of the digital and Photoshop revolution and related image manipulation in the 1990s onward, attempts to outmanoeuvre the limitations of early technology threatened to compromise not only photojournalists of the day, but the craft as a whole.

In 1916, Britain introduced a policy known as “Propaganda of the Facts.” It banned staged or fake images, warning they undermined Allied credibility. Hurley’s composites also came under fire, though their use was limited, not banned outright.

In the Second World War, the Canadian military ensured it would be one step ahead of the popular press by mustering its own photographic corps in the form of the Canadian Army Film and Photo Unit, the Royal Canadian Air Force Press Liaison Section and the Royal Canadian Navy Photographic Section.

“A pictorial record should accompany the compilation of the War Diary,” said the director of naval information, Lieutenant (N) John Farrow. “Men die, ships sink, towns and ports change their contours, and without the aid of the camera their images are left to the uncertain vehicle of memory or to be forgotten in the dry passages of dusty files.”

“Men die, ships sink, towns and ports change their contours, and without the aid of the camera their images are left to the uncertain vehicle of memory.”

His guiding principle: “At all times Headquarters could, at will, issue to the Press photographs of events or of persons that might be considered of topical interest.”

William Ivor Castle also used composites to overcome the shortcomings of First World War-era equipment. [Wikimedia]

Below is an early rendition of his magnum opus, “The Taking of Vimy Ridge,” a 6.1-by-3.35-metre composite printed in five sections. [William Ivor Castle/LAC/3628659]

Could. At will. Of topical interest.

It would all be in the hands of the military. Freedom of the press took a back seat to what would become known as operational security or, in plain speak, message control.

There would be no independent Canadian photojournalists in the Second World War.

There was, however, Donald Grant—a lieutenant in the film and photo unit who became the only photographer ever to record a soldier in the act of earning a Victoria Cross.

He did so in France, photographing Major David Currie of the South Alberta Regiment accepting the surrender of German troops at St. Lambert-sur-Dive on Aug. 19, 1944.

There was no Canadian photographer with the troops at Dieppe. The only photographic record of the event is German.

Gilbert Alexander Milne’s photograph of troops landing at Bernières-sur-Mer, France, on June 6, 1944, has become the iconic image of Canadians on D-Day.

It lacks the drama of famed combat photographer Robert Capa’s textured, action-packed images of Americans at Omaha Beach, but Milne’s photographs form a well-executed, technically sound record of one of the most important days in Canadian military history.

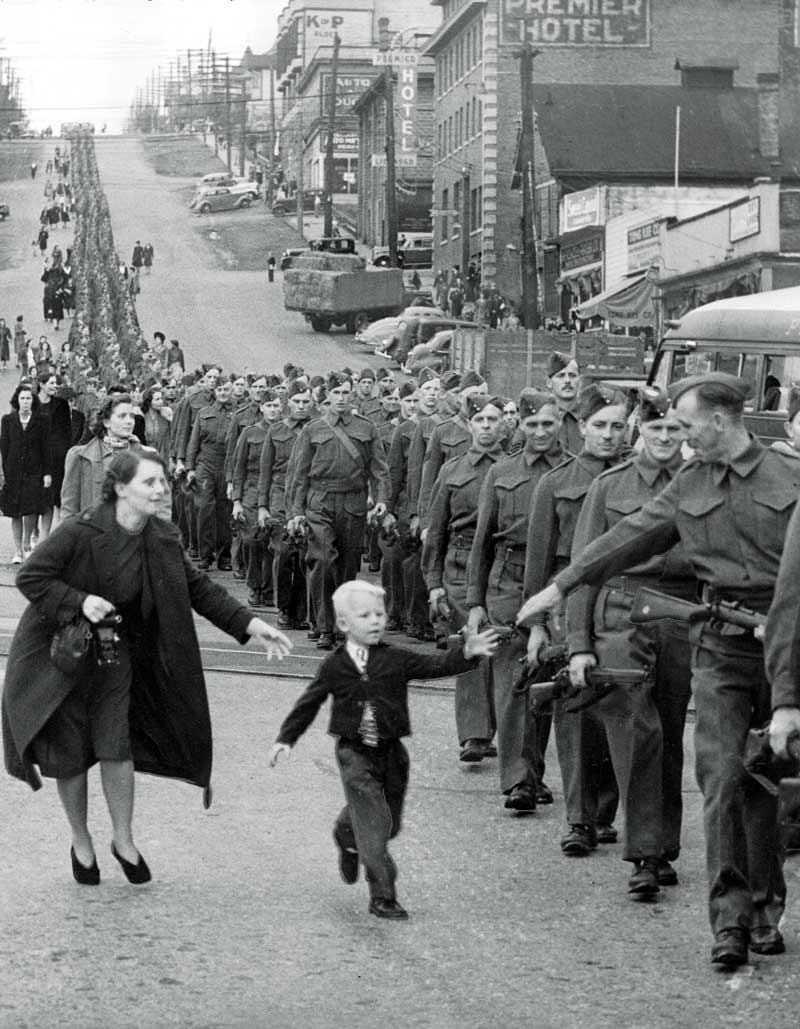

Perhaps Canada’s most iconic Second World War photograph wasn’t taken on the battlefield, or even overseas, but at home on 8th Street in New Westminster, B.C.

The photographer was Claude P. Dettloff of The Province newspaper, and his picture was of five-year-old Warren (Whitey) Bernard breaking from his mother’s grasp to reach for the outstretched hand of his father, Private Jack Bernard, a rifleman marching off to war with The British Columbia Regiment (Duke of Connaught’s Own).

It was Oct. 1, 1940. Germany had conquered Europe and was at Britain’s doorstep. In 1944, Bernard landed at Juno Beach and fought all the way to Germany. He survived the war, but his marriage didn’t. The photograph, entitled “Wait for Me, Daddy,” would be one of the last of the Bernard family together.

The image was published all over the world. Warren would go on to appear in victory bond drives, a blond boy in blazer and short pants appealing to the masses to “buy bonds; bring my daddy home.”

The photograph hung in every B.C. school for the war’s duration. It was depicted in a statue, reproduced on a coin and emblazoned on a stamp. But the Canadian war produced no “Flag Raising on Iwo Jima” picture for the country to immortalize.

Lieutenant Donald I. Grant[Frank L. Dubervill/LAC/3524310]

The Donald Grant shot of Major David Currie accepting the surrender of German troops in 1944 France is believed to be the only photograph of a Victoria Cross action.[Donald I. Grant/DND/LAC/PA-111565]

Gilbert Alexander Milne’s D-Day picture of Canadian troops hitting the beach in France is an icon in Canada’s Second World War archive[Gilbert Alexander Miline/LAC/3408540]

Claude Dettloff’s “Wait for Me, Daddy.” is an icon in Canada’s Second World War archive[Claude Dettlof/City of Vancouver Archives]

Canada’s most iconic Second World War photograph wasn’t taken on the battlefield, but at home in New Westminster, B.C.

“The censorship of the war and the fact, as fellow soldiers they did not take pictures of dead Canadians and were sparing about showing the wounded…means their version of the war was sanitized,” historian Dan Conlin said while promoting his 2015 book, War Through the Lens: The Canadian Army Film and Photo Unit 1941-1945. “However, they captured many grim things about war—starving and frightened civilians, scared and wounded prisoners and war’s terrible destruction.”

The film and photo unit was disbanded after shooting 60,000 still photos and 6,000 newsreel stories. Much of its original, uncensored film was lost in a fire at the National Film Board in 1967.

Tomelin’s Korean War photograph stands with the best produced by the likes of American David Douglas Duncan, the war’s pre-eminent photojournalist.

In the succeeding decades, Canadians such as Larry Towell, Lana Šlezić, Finbarr O’Reilly, Louie Palu and others have distinguished themselves as war photographers, elevating the art and the craft of photography in the most trying of circumstances.

Advertisement