A girl clutches her doll as she waits with her luggage before leaving London for Canada in May 1940. [David Savill/Topical Press Agency/Getty Images/3355787]

Citizens of Saskatoon couldn’t contain their excitement when the British children arrived by rail in the late summer of 1940. The largest crowd since the Royal Visit of 1939 was at Union Station to greet the young newcomers. Huge crowds also greeted a party of British children at the Port of Montreal. In Toronto, they were cheered enthusiastically. Who were these children who drew such a warm welcome after arriving from wartorn Britain?

These were children evacuated to Canada by a British government-financed agency known as the Children’s Overseas Reception Board (CORB).

Even before Great Britain declared war on Germany in September 1939, fears of a German invasion were widespread. In fact, the British government had begun slowly planning for war with Nazi Germany soon after Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor in 1933. The fear of an invasion and occupation by the German army raised concern about the safety of British children. By 1935, a plan had been developed to evacuate youngsters from large cities to the countryside. Four years later, overseas evacuation entered the picture.

When Canada was pursuing an exclusionary immigration policy, driven largely by the Great Depression, concerned Canadians urged the federal government to admit large numbers of British children in the event of war. A few Canadians even lobbied Ottawa to grant entry to refugee children from the Continent, most of whom were Jews. Among these Canadians was Senator Cairine Wilson, who headed the Canadian National Committee on Refugees, which sought a liberalization of Canada’s immigration policy.

The committee petitioned Ottawa to have 100 youngsters brought from Britain, where they were then living, to Canada for adoption or guaranteed hospitality. Prime Minister Mackenzie King opposed the idea of Canada getting involved in such a scheme before it declared war on Germany, but he did agree to the admission of 100 children as an experiment.

The experiment was torpedoed, however, by Frederick C. Blair, director of the Immigration Branch of the Department of Mines and Resources. The perfect instrument of the government’s anti-immigration policy, Blair set out to thwart the committee’s aims by producing three pages of stringent regulations. As a result, only two children were admitted under the scheme.

After Britain declared war on Germany on Sept. 3, 1939, almost three million children were evacuated from large cities to rural areas as authorities predicted massive civilian casualties from the bombing of British cities. When this did not happen, many of these youngsters returned to their families. Others remained in the countryside.

Members of the third contingent of guest children arrive in Montreal from Britain on July 7, 1940. [Montreal Gazette/LAC/PA-142400]

After the initial lull in military action, known as the Phoney War (see page 20), ended in April 1940, overseas evacuation began in earnest. By then, the triumphant German war machine was sweeping through western Europe, toppling one government after another. In June, France fell and an attack across the English Channel was believed imminent. In that summer of rising hysteria, a new wave of internal evacuations from London and eastern England got underway. But some parents sought safety for their children farther afield, and in the summer of 1940, a stream of children sailed for North America.

Initially, the evacuations were done privately. Parents arranged for their children to stay with relatives or friends in Canada and the United States. But in some cases, entire schools made the overseas journey. Universities and churches as well as British companies with offices in Canada also set up evacuation programs. However, since many of these youngsters came from well-off families, there were complaints in the British Parliament and press that the affluent were looking out for their own while children from poor families were being overlooked.

Fortunately for the children of the less well-off, another option presented itself that summer. In response to a flood of offers from the Empire, an embarrassed British government announced plans in June to evacuate children to Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Canada. The scheme would be operated by CORB, which would pay the children’s transportation costs. In the summer of 1940, some of the children who arrived in Canada came under private auspices, but by far the largest number arrived courtesy of CORB.

The British government initially resisted sponsoring overseas evacuations, one of the strongest opponents being Prime Minister Winston Churchill. In fact, he and his wife Clementine detested the very idea of it. Churchill regarded it as defeatist and a waste of invaluable shipping.

When he was asked by an official if he might like to see the senior child of the first CORB party deliver a message to Canada’s prime minister, Churchill replied, “I certainly do not propose to send a message by the senior child to Mr. Mackenzie King, or by the junior child either. If I sent a message to anyone, it would be that I entirely deprecate any stampede from this country at the present time.”

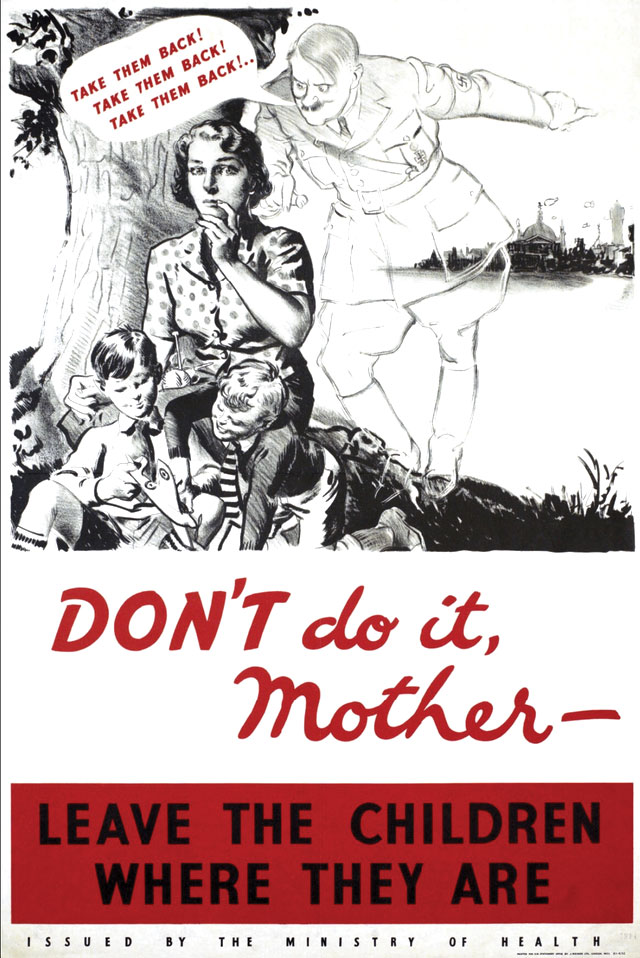

A Ministry of Health poster advises mothers to leave their children in rural areas while the Blitz on England’s cities continues. [IWM/PST3095]

The crisis of 1940 altered the Canadian government’s attitude toward refugees, who had been decidedly unwelcome during the Great Depression. Thomas Crerar, the minister responsible for immigration, proposed that Canada admit at least 10,000 children between the ages of five and 15, according to historian Geoffrey Bilson. The minister of finance worried about the costs, but the cabinet accepted Crerar’s proposal at the end of May. Blair, not surprisingly, was not keen on letting British children into Canada, but he was prepared to follow orders.

When CORB opened its doors in June 1940, it was inundated with applications. More than 250,000 children were registered before the application period closed after only two weeks.

While private overseas evacuations continued, the government agency proceeded to process its applications, employing a system already set up for massive internal evacuation of London and other vulnerable counties.

To be eligible for overseas evacuation by CORB, children had to come from areas likely to be attacked, be in good health, and have a satisfactory school record. At least 90 per cent had to be enrolled in state-run schools and 40 per cent in total had to come from Scotland and Wales.

Most of the children who were eventually selected were Protestant because most of the families offering to provide homes for them were Protestant. Jewish organizations offered to find homes for Jewish children, but the Canadian Immigration Branch discouraged the evacuation of Jewish children. For its part, learning from the abuse and hardship suffered by relocated children of the British Home Children migration scheme that started in 1869, the Canadian government also insisted that no child would be sent to a family on relief or to one where children had to work for their keep.

About 7,500 British children, known officially as British Guest Children, were evacuated to Canada between 1939 and 1941. Of these, 1,532 arrived under the British government scheme. After debarking at a Canadian port, they were received by immigration officials, who then arranged for their transportation under supervision to provincial clearing centres, where provincial authorities took charge.

Five of the six guest children rescued from a lifeboat with 40 other survivors pose with members of the warship that picked them up after the sinking of SS City of Benares on Sept. 17, 1940. The lifeboat was spotted after being adrift for eight days by the crew of a Sunderland flying boat. Food was dropped to them by parachute and the ship was directed to their location. [Associated Press/400913062]

Tragedy struck on Sept. 17, 1940, when SS City of Benares, carrying 90 CORB children, was sunk by the German submarine U-48 in the North Atlantic Ocean after naval escorts had left the convoy, believing it was in safe waters. Only 13 of the children were rescued, after being found huddled in lifeboats and suffering from hypothermia.

When the U-boat crew returned to base in France, they wept after learning that the City of Benares had been transporting children. The captain of HMS Hurricane, which steamed 480 kilometres to the rescue and picked up most of the ship’s survivors, was also deeply affected.

When Lieutenant-Commander Hugh Crofton Simms received the Mayday call and realized that there were women and children on board the City of Benares, he ordered Hurricane to proceed as fast as possible to the site of the sinking. He reached the estimated position at 2:20 the following afternoon, his vessel whipped by gale-force winds and mountainous waves.

When he arrived, he found the scattered remains of all the lifeboats, nearly every one of which held dead children. According to his son, Simms dedicated the rest of his life “to the destruction of the Hun.”

Fred Steels was 11 at the time. He and the other CORB youngsters were already bedded down below deck when the torpedo hit. Most of them were travelling without their parents. Against all odds, Steels survived the sinking. He recalled decades later that the water had rushed in and that a bunk had crashed down on top of him. “When I got out of the cabin there was a huge hole in the deck, and a dirty great seaman grabbed me and another boy and threw us into a lifeboat,” he said.

In the wake of this attack, the British government suspended and then terminated the CORB evacuation plan. The agency sent no children to Canada and the other dominions in 1941. Death at home in Britain among family was deemed preferable to death at sea. Moreover, by the spring of 1941, the demand for overseas evacuation of children had ended as the threat of a German invasion of Britain was fading. Obtaining warships for convoy duty was also proving difficult.

Most of the British Guest Children adjusted well in Canada where, even in wartime, life was comparatively luxurious and where there were no air raids or blackouts and food was abundant. In fact, many eventually returned to Canada as immigrants.

One of those was W.A.B. Douglas, who had a long naval and public-service career, becoming official historian of the Department of National Defence before retiring from the federal government. The son of a widowed mother, he sailed in July 1940 from Liverpool to New York, then took the train to Toronto. He joined the family of a well-off businessman and his wife, a friend of his mother.

His mother missed him terribly, but in 1943, she was able to arrange for him to return home on HMS Pursuer as a “guest of the British Admiralty.” Douglas did so on the understanding that if the war were still raging when he reached the age for military service, he would join the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve.

As it happened, the war ended before he reached military age. His mother married a Canadian army chaplain in 1945 and sailed to Canada as a war bride in 1946. Consequently, after leaving school in 1947, Douglas set off to join his parents in Canada, sailing as a “military dependent”—the only male military dependent among hundreds of war brides. On his return to Canada, he could once again enjoy the pleasures and amenities he had enjoyed as a British Guest Child.

Advertisement