“The importance of prevention of disease on field service cannot be over-estimated. Neglect of sanitary measures inevitably results in great loss of life, and disease may assume such proportions as to paralyze the efficiency of a force.”

—the 1914 British Field Service Pocket Book

Wretched living conditions in a network of muddy, squalid trenches remains the most common collective image associated with the life of front-line soldiers during the Great War. One needn’t be an expert in microbiology to realize that such crowded, unsanitary conditions were a prime breeding ground for disease. Typhoid, cholera, diphtheria and dysentery, to name only a few, should have flourished in the crowded trenches, camps, hospitals and depots of the First World War, sapping the army’s manpower and ability to fight.

Yet, that didn’t happen to Canada and its Allies. Despite the high casualty rates, the First World War represented a marked departure from previous conflicts when it came to fatality statistics: disease, once the prime cause of death among soldiers during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, had lost its place as the biggest single killer of soldiers.

This was no accident or anomaly. For the Canadian Expeditionary Force, it was the result of the sanitary sections and mobile laboratories combined with command’s willingness, at all levels, to take well-being seriously.

A 2020 study estimated that the deaths of 450 Canadian First World War soldiers overseas could be attributed

to influenza—only 0.1 per cent of the CEF contingent.

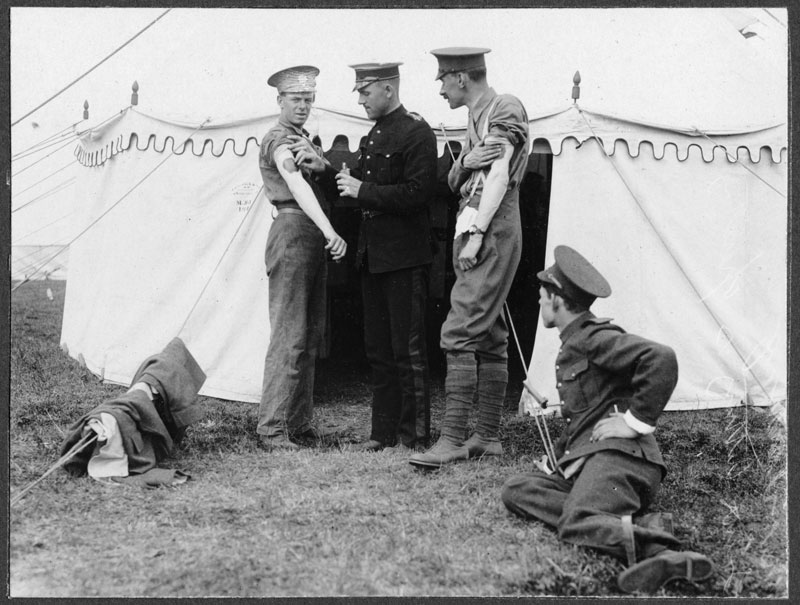

Mobilized as part of the Canadian Army Medical Corps (CAMC), sanitary sections and mobile laboratories acted as public health units in uniform. Their role, in a nutshell, was to identify, monitor, prevent and control the spread of disease in the areas of operation. Following the British example and, no doubt, aware of the threat posed by disease, Canada mobilized 10 sanitary sections and five mobile laboratories for its overseas force of 424,000 during the entire conflict. To put that commitment in perspective, if the Canadian government had made the same public health effort for the country’s population during the recent COVID-19 pandemic, the nation would have been serviced by 894 new specially mobilized federal public health units and 448 travelling laboratories. Had this public health expertise and guidance not been available from the start of the conflict, the health impact could have been considerably worse.

The armies of the time had good reason, based on generations of painful experience, to take disease prevention seriously. During the U.S. Civil War, for instance, about two-thirds of the 620,000 recorded deaths were because of disease.

The 1899-1902 Boer War, meanwhile, was also referred to at the time as the “typhoid campaign,” and with good reason: 84 per cent of imperial soldiers were, at some point, diagnosed with an infectious disease. Indeed, based on a 1911 study by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, disease accounted for 64 per cent of imperial military fatalities during the conflict. As the war progressed, that percentage worsened, increasing to 74 per cent in 1900-1901 and peaking at 78.8 per cent in 1901-1902. The study’s author, R.J.S. Simpson, summarized the seriousness of the forces’ failure to fight disease with the morbidly cheeky assertion that, moving forward, they must find a way to “teach the man that it is his duty to preserve himself from disease in order that he may have a better chance of being shot.”

Even worse than the plight of imperial and Canadian soldiers in South Africa was that of U.S. troops during the 1898-1899 Spanish-American War. Disease caused 88 per cent of American service deaths, many of which took place in the training camps at home, well before the soldiers even met the enemy.

By 1914, Western armies and their medical doctors could no longer claim ignorance when it came to the cause of diseases such as typhoid or scarlet fever. No longer a matter of speculation or insinuation, the scientific discoveries of the latter 19th century confirmed the microbiological origins of a growing number of diseases and, by extension, their environmental sources and means of transmission. For example, in the 1880s, German scientist Robert Koch proved the connection between micro-organisms and diseases such as cholera and tuberculosis. At the same time, doctors generally agreed on the principles and practices of investigation and reporting disease.

In British militaries, the concept of uniformed public health units servicing the army began in the early 1900s. In 1908, the first dedicated army public health unit, 1st London (City of London) Sanitary Company, was formed. It expanded into a network of subordinate sanitary sections during the war. Canada, as part of the imperial command structure, mirrored the British system, albeit without a central company, as its divisions were mobilized and sent to Europe.

As with all public health units, the precise tasking of sanitary sections and mobile laboratories depended on their location and circumstances. Units such as the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 10th Canadian Sanitary Sections were deployed in the field with their respective divisions—or in the case of the 10th, their field force in Siberia. Other sanitary sections were employed in camps, depots and hospitals staffed by the Canadian army in Great Britain.

Overall, the primary responsibilities of a sanitary section included inspection of unit lines and accommodations for identification and elimination of sources of disease. Especially in front-line areas, sanitary sections were tasked with inspection, filtration and distribution of water supply. On the other end (literally and figuratively), was ensuring the safe disposal of sewage and refuse.

In both trenches and in the supporting camps and billets, sanitary sections made certain that sleeping quarters, bars, canteens and storage areas were properly sterilized and ventilated. Plus, those units assigned to camps and hospitals would routinely disinfect clothing, blankets, medical tools and hospital bedding. Regardless of their specific tasks, Canadian sanitary sections were also responsible for reporting any public health concerns.

The local Conditions were described as dire, with “deposits of fecal matter lying everywhere,” and where “the walls of the houses are literally black with flies.”

Mobile laboratories, meanwhile, were focused on analyzing the origin of disease outbreaks such as typhoid, diphtheria, trench fever, tuberculosis and influenza. As such, they would examine pus, blood and other morbid products and would perform autopsies. And as part of their routine, mobile laboratories would test water supplies. With the introduction of chlorine gas as a weapon of war, mobile laboratories were unexpectedly also thrust into investigating the chemical contents of the gas used on Canadians.

Finally, as all Canadian army formations were required to routinely detail members of their units to sanitary duties, the sanitary sections and mobile laboratories also served in an advisory and educational capacity to personnel tasked with sanitary work. By 1917-1918, the Canadian Expeditionary Force’s network of sanitary sections had already designed their own centralized training course syllabus and catalogue of sanitary applications and appliance designs.

Disease, once the prime cause of death among soldiers during the late 19th and early 20th CENTURIES, had lost its place as the biggest single killer of soldiers.

Whatever a typical day or week was like for a sanitary section or mobile laboratory depended on the circumstances of where they happened to be at any one time. Here are just a few examples, drawn from unit war diaries and other archival sources, of the work.

No. 2 Canadian Sanitary Section was mobilized at Montreal’s McGill University in 1915 under the command of Thomas Albert Starkey, a professor of hygiene and one of many skilled academics turned CAMC officer. No. 2 was deployed to the area of Kemmel-

La Clytte in Belgium in October 1915, where, as was often the case, it first focused on providing safe water to the division. The situation was, in the words of Starkey, “acute.”

Shortages of drinking water prompted the men of the division to draw their water, unfiltered, from a brook that originated from behind the German lines. Working with the divisional engineers, Starkey’s section constructed an improvised filtration apparatus at a local lake where the water was chlorinated and from which a system of pipes brought the water forward to designated collection points.

In April 1916, meanwhile, while on a routine water inspection, Lieutenant-Colonel George Nasmith, the commanding officer of No. 5 Canadian Mobile Laboratory, and his technicians witnessed the close gas attack on the Canadians at Ypres, which resembled “a long cloud of dense yellowish-greenish smoke rising and drifting in our direction.”

“The gases reached us within half an hour,” reported Nasmith, “and we had diagnosed it as largely chlorine but with probably some bromine present.”

The unit immediately focused on confirming the exact composition of the gas used. Apart from their own observations, this involved interviewing and examining the wounded, as well as conducting lab tests. The results would inform what personal protection could be designed and used.

Then, toward the end of the war, No. 3 Canadian Sanitary Section, mobilized in Toronto, was following its assigned division during the Hundred Days Offensive. In mid-October 1918, as it set up camp in Douai, France, the local conditions were described in the unit’s war diaries as dire, with “latrines overflowing,” “deposits of fecal matter lying everywhere,” and where “all premises contain heaps of decaying organic matter” and “the walls of the houses are literally black with flies.”

The unit spent October 19-20 constructing fly-proof public latrines and urinals and examining and labelling 16 wells in the area. The following week, its focus shifted to helping local war refugees, approximately 1,000 of whom were concentrated at the city barracks. The unit’s commander, Major Harold Orr, reassigned part of his unit to the camp.

“Large numbers of these persons have been brought in in a very weak condition,” reported No. 3’s war diary. “They have been impoverished on the German diet, and influenza had developed among them. It is probable that many more cases of influenza will develop in the next few days.

“These people are very difficult to handle, one member of a family will not permit himself to be removed to a hospital unless the whole family are taken. The children and some of the adults do not bother using latrines but defecate on the ground in exposed places. They throw their food refuse on the ground, they have no idea about cleanliness, they are very much depressed mentally.”

As detailed in the war diary of No. 3, the spread of influenza posed an additional threat to the operations of Allied armies during the final offensive. Yet, the sheer fact that the push continued despite the disease’s presence could also be seen as a testament to the ability of sanitation units in containing and mitigating the challenge, which would have been impossible 20 years earlier.

So, while there was ample evidence of influenza’s devastating impact on civilians in Europe and North America, its effect on the Canadian Expeditionary Force, though by no means negligible, was never severe enough to compromise operational capability in the waning months of the war. A 2020 study by Robert Engen of the Canadian Forces College estimated that the deaths of 260-450 Canadian First World War soldiers overseas could be attributed to influenza—less than 0.1 per cent of the CEF contingent. Though certainly on guard against the disease, the records of the sanitary sections and mobile laboratories nonetheless took on a business-as-usual approach at the time, suggesting that policies and procedures were in place, up to date and capable of handling the challenge.

This quiet confidence, even in the face of a pandemic, is reflected in Nasmith’s memoir: “There must be some basic reason for this freedom from contagious diseases, for we know that such freedom does not come by accident.”

Advertisement