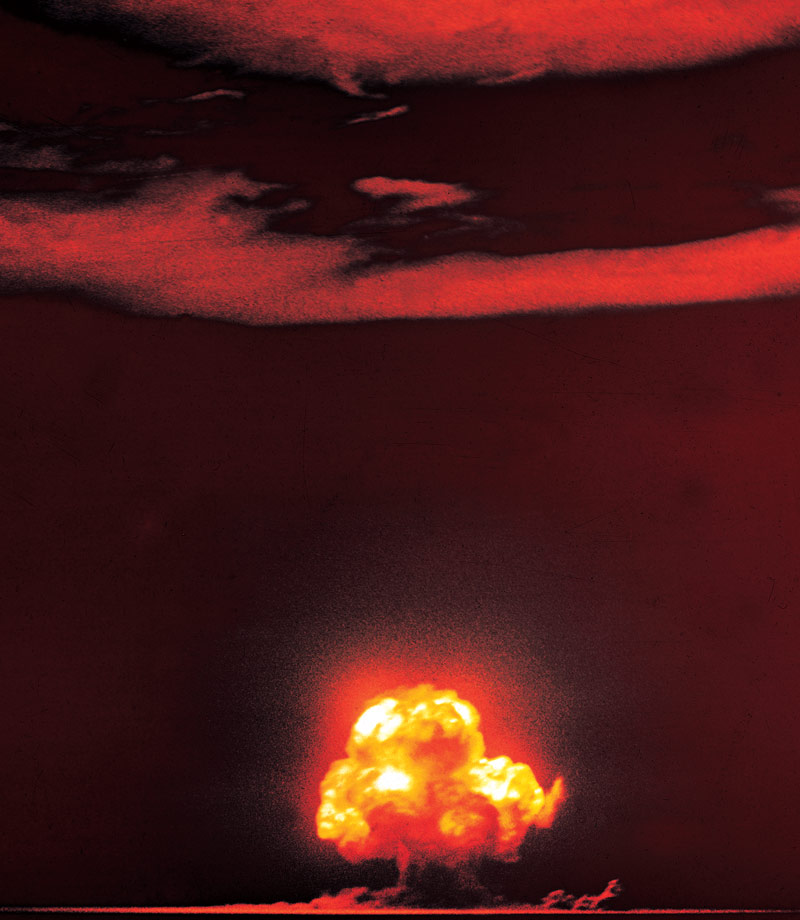

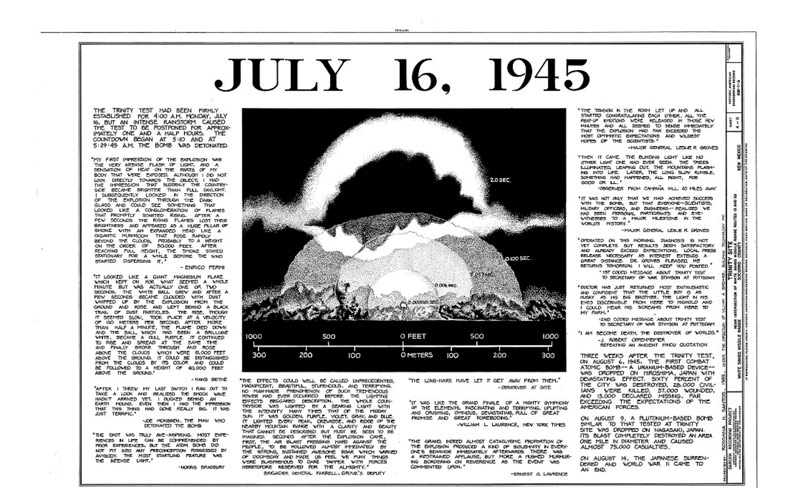

A photo of, and an engineering report on, the first test of the atomic bomb in New Mexico. [LIFE Photo Archive/Wikimedia; Albuquerque Historical Society]

In December 1942, a group of scientists led by Enrico Fermi demonstrated the first controlled nuclear chain reaction in an abandoned squash court at the University of Chicago. The race to build the first atomic bomb had begun.

One of the first items the Manhattan Project, as the initiative was known, needed was a supply of uranium. Much of it came from a mine on the shores of Great Bear Lake, N.W.T. The Eldorado mine, owned by Gilbert LaBine, had been closed at the outset of the Second World War. In 1942, LaBine received a phone call from C.D. Howe, minister of munitions and supply, who said: “I want you to reopen. Get together the most trustworthy people you can find. The Canadian Government will give you whatever money is required…. And for God’s sake don’t even tell your wife what you’re doing.”

By the end of 1943, Eldorado, now owned by the government, had produced the 60 tonnes of uranium oxide the Americans needed. The ore was mined by local Dene who were paid $3 a day to haul 45-kilogram sacks of radioactive ore out of the mine and put it on barges on the Mackenzie River.

Howe offered the Americans Alberta as a test site for the first atomic bomb, but they preferred New Mexico. Dozens of scientists and military personnel went to Los Alamos and worked feverishly for two and a half years.

Robert Oppenheimer, a left-leaning American physicist with no experience in administrating a large project, was to spearhead the initiative.

Oppenheimer proved to be the perfect candidate. At dawn on July 16, 1945, the first nuclear bomb was tested near Alamogordo, N.M. Scientists and military personnel watched as the now familiar mushroom cloud rose into the sky.

Years later, Oppenheimer looked back on that moment and noted: “We knew the world would not be the same.” He quoted from the Hindu text, Bagavad Gita, “Now I am become Death, the Destroyer of Worlds.”

The project’s scientists were joyful about the breakthroughs in physics, but ambivalent about the fact they were creating a weapon. “We had somehow thought it would not be dropped on people,” Oppenheimer said later.

But on Aug. 6, 1945, a bomb labelled “Little Boy” was unleashed on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Three days later, another bomb, this one called “Fat Man,” hit Nagasaki. The death toll from the two cities was estimated from 150,000-250,000.

When faced with the destruction and suffering of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Oppenheimer wondered if the living might not envy the dead.

The Japanese weren’t the only casualties of the atomic age. The Dene miners who had delivered the uranium, often coated in its dust, died of cancer at frightening rates. Their settlements on Great Bear Lake became known as the “Villages of Widows.”

Advertisement