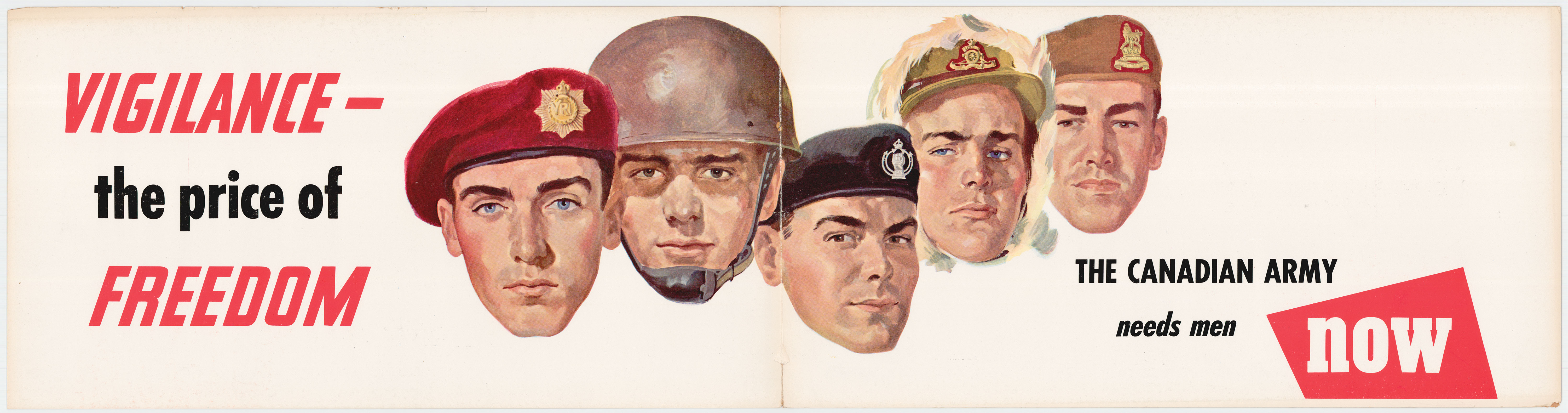

Recruitment posters tapped into subconscious emotions to raise support for the war effort, appealing to idealistic values and playing on fear. [CWM/19750317-021; 19920196-054; 20010129-0610; 19920196-149]

Canada was unprepared for the Second World War. It had only a score of aircraft and a handful of destroyers. Its army was small and lacked modern equipment. And coming out of the Depression, with the sacrifices of the First World War still vivid, Canadians were less than unanimous in their support.

But how to rally people to the cause in the pre-television era? Posters were the answer. They were relatively cheap, could be quickly and widely distributed and, once fixed to a wall, tended to stay there a long time. In skilful hands, their words appealed to reason, and their images tapped immediately into people’s subconscious emotions. They were the ideal propaganda tool for the time.

In the year ending in March 1942 alone, the Bureau of Public Information distributed more than 1.2 million posters. The Wartime Information Board, which succeeded the bureau in 1942, produced about 700 different propaganda posters, flooding the country with millions of copies.

Poster images festooned bulletin boards in post offices and grocery stores, hoardings at building sites, sides of buses and streetcars and were displayed in schools and government offices. They even appeared on matchbook covers.

Early in the war, their job was to raise morale and entice volunteers into uniform. Posters helped build public support by tapping into shared feelings of patriotism and values of national identity and morality. They exploited men’s sense of duty and attraction to adventure. Volunteers were cast as modern-day knights on wheeled or winged steeds.

As the war went on, cold reality set in and the messages changed, introducing the fear of failure and consequent threat to civilians. As casualty lists lengthened, recruitment posters mined the shared feeling for vengeance, to fight until the job is done.

They used strong words, bright colours and bold designs to catch people’s attention and convey complex messages about national unity, individual responsibility, shared duty and the virtue of the collective cause. [CWM/19910001-879; 19930002-004]

As more and more troops were needed, recruitment posters aimed at freeing up men for combat by encouraging women to join the services for support work, or pick up tools for war-related jobs on the home front. They also enticed First World War veterans into the Veterans Guard of Canada.

There is no doubt the poster campaign helped rally Canada’s 11 million people to the war effort. By war’s end, $12 billion had been raised in Victory Bond campaigns and a billion kilograms of foodstuffs sent to beleaguered Britain. More than a million men and women served in the army, navy, air force and merchant marine. A million and a quarter more worked in war-related industry, building the fourth largest air force and fifth largest navy fleet in the world.

Pen and ink proved as mighty—and necessary—as the sword.

Posters recruited women to free up men for combat, and thousands served as clerks, mechanics, messengers and drivers. More than 21,000 women volunteered for the army, 7,100 joined the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service and more than 17,000 were recruited for the Women’s Division of the Royal Canadian Air Force. Female pilots shuttled aircraft around behind the lines, enabling 900 male pilots to join fighter and bomber crews. [CWM/19960059-002]

Advertisement