Artist John Trumbull depicts the death of American General Richard Montgomery during the 1775 invasion of Quebec. [John Trumbull/Yale University Art Gallery/Wikimedia]

In 1775-76, Canada very nearly became one of the American colonies. Its fate would hinge on a cold morning battle in a snowstorm at the gates of Quebec.

Sixteen years earlier, British forces had defeated the French on the Plains of Abraham and occupied the fortress of Quebec. France ceded Canada to Britain in the 1763 Treaty of Paris and consigned New France’s nearly 70,000 inhabitants to British, Protestant rule. Britain had obtained a French-speaking Catholic colony, the Province of Quebec (commonly referred to by contemporaries as Canada), without loyalty to the new regime or its king. The Canadiens feared for their way of life.

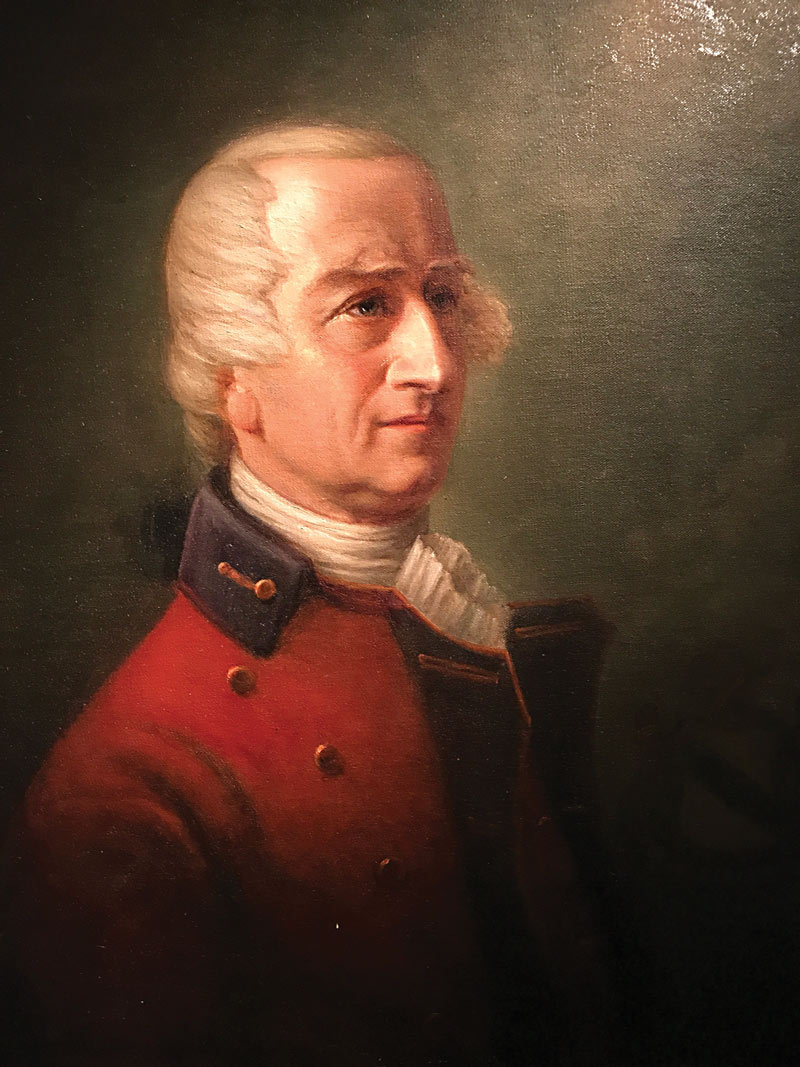

The Governor of Quebec, Major-General Guy Carleton, was worried about growing discontent in the American colonies. He was also unsure of the position the Canadiens would adopt in the event of an American revolt. The province had few defences, and Carleton needed the backing of the influential Catholic clergy and local aristocracy, the seigneurs, whom he felt capable of dissuading the Canadiens from joining an American insurrection.

Accordingly, Carleton was instrumental in the British Parliament’s passing of the Quebec Act, 1774, which guaranteed the rights of the Catholic Church, the rights of Catholics to hold office and the continuance of the French legal and land tenure systems in Quebec. The act also greatly extended the boundaries of the Province of Quebec, to encompass the Great Lakes region all the way west to the confluence of the Mississippi and Ohio rivers. The move essentially blocked the mainly coastal 13 American colonies from western expansion. The Quebec Act seemed a betrayal to the rebellious Americans. They saw Britain as the enemy and Canada as potentially easy prey.

Carleton was also keenly aware that there were American sympathizers among the 2,000 British colonists in the province, especially since many had moved north from the American colonies. This was especially true of the British merchant class who were unhappy because the Quebec Act threatened their commercial and political power.

In 1774-75, American agents spread anti-British propaganda among the Canadiens, arguing that through revolution they would be liberated from British rule. But they also reminded the Canadiens, threateningly, that the latter were “a small people, compared to those who with open arms invite you into fellowship.”

The American rebels, then, could also come as conquerors, not liberators.

Perhaps the best that the British and Americans could hope for was the neutrality of the Canadiens, who watched their former enemies slide toward fratricidal conflict.

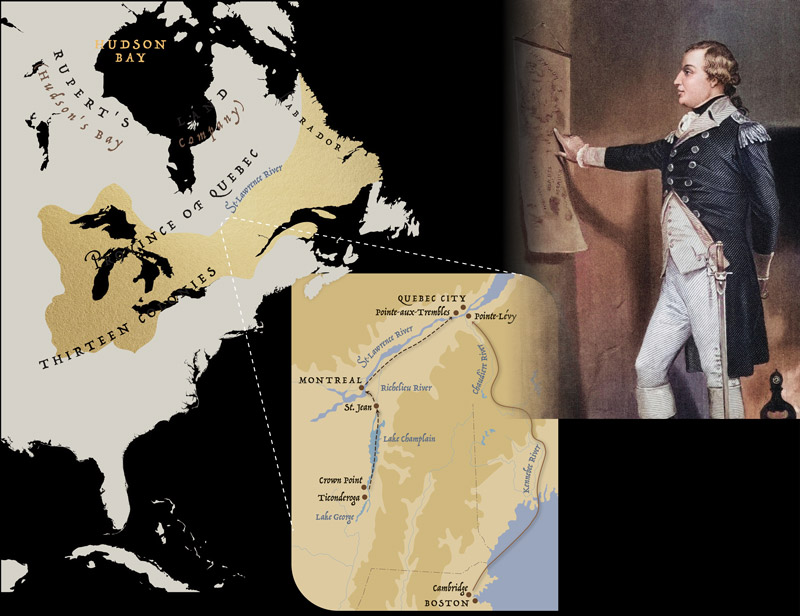

The American Revolution began in April 1775 with fighting at Concord and Lexington. Events moved quickly. In May, American forces seized British forts at Ticonderoga and Crown Point, traditional launching points for attacks into Canada.

The American Continental Congress decided to invade Canada to encourage revolt there and to prevent the British from using it as a base for attacks against the rebels in New York and Massachusetts. Congress ordered Major-General Philip Schuyler at Ticonderoga to seize the British fort at St. Jean, then Montreal.

Brigadier-General Richard Montgomery assumed command of the American attack in September 1775. [Historical image collection by Bildagentur-online/Alamy/2WBJ916]

Carleton commanded only 944 regular forces spread throughout Quebec, most garrisoning forts along the Richelieu River. What he desperately needed was the support of the militia made up of Canadiens and loyal British settlers. But French speakers proved hesitant, notwithstanding the clergy’s call to arms.

More positively, the experienced Lieutenant-Colonel Allan Maclean raised a new, very reliable regular unit, the Royal Highland Emigrants, consisting mainly of Scottish Highlander settlers recruited in Canada. Many were combat veterans and immediately available for the province’s defence.

On Aug. 30, a force of about 2,000 mainly inexperienced New Yorkers left Crown Point for St. Jean. They arrived five days later depleted by sickness, their commander Schuyler himself too ill to continue. Brigadier-General Richard Montgomery assumed command and laid siege to the fort.

Carleton staked almost everything on the defence of the fortification at St. Jean as Montreal’s walls were very weak and were unlikely to withstand a determined attack. The St. Jean fort was garrisoned by 512 regulars, 20 Highland Emigrants and 90 Canadien militia. Its commander, Major Charles Preston, held out as long as he could.

But, on Oct. 17, the British 20 kilometres to the north swiftly surrendered to a small American force. With its many supplies captured by the invaders, any hope of relieving St. Jean ended. Preston surrendered on Nov. 3 after a heroic resistance, and most of Carleton’s best troops were now prisoners.

American Colonel Benedict Arnold led a separate force to Quebec City, which was attacked on Dec. 31, 1775. [Niday Picture Library/Alamy/E9M50A]

The Quebec Act seemed a betrayal to the rebellious Americans. They saw Britain as the enemy and Canada as potentially easy prey.

Perhaps sensing the turning tide, some of the 900 Canadien militia in Montreal began to drift away, much to Carleton’s bitter disappointment. Meanwhile, other Canadiens joined the invaders. The population’s attitude was a result of perceived British weaknesses and the likelihood of their defeat. Carleton believed that “every Individual seemed to feel our present impotent Situation.” Why take up arms for the British and then incur a victor’s wrath? Most Canadiens instead stayed on the sidelines.

To make matters worse, Carleton learned that a force of Americans commanded by Colonel Benedict Arnold had reached Pointe-Lévy, on the St. Lawrence River opposite Quebec City, on Nov. 8. They had travelled some 500 kilometres by boat and on foot over the rugged and largely uninhabited wilderness of upper Massachusetts (now Maine) following the Kennebec and Chaudière rivers.

Historian George Stanley marvelled at the Americans’ epic “feat of endurance” and their abilities to navigate “over trackless swampy wastes, through rivers choked with ice and over dangerous rapids, the men suffering from cold, hunger and exposure.”

It had taken them seven weeks and of the 1,050 men from Massachusetts, Pennsylvania and Virginia who had begun the trek, only about 700 remained, the others having turned back, become lost or perished. They were exhausted and starving, their clothes in tatters, and some soldiers had survived by making soup from their leather shoes and belts; many suffered from debilitating dysentery.

Once in Canada, they purchased supplies from the Canadiens at exorbitant prices. On Nov. 13-14, Arnold’s force assembled 40 small craft and crossed the St. Lawrence. Their ranks too few to besiege Quebec City, after several days the invaders established a camp at Pointe-aux-Trembles, 32 kilo-metres to the west, and awaited Montgomery’s arrival from the southwest.

American Colonel Benedict Arnold led a separate force to Quebec City, which was attacked on Dec. 31, 1775. [Niday Picture Library/Alamy/E9M50T]

The Quebec Act seemed a betrayal to the rebellious Americans. They saw Britain as

the enemy and Canada as potentially easy prey.

Montreal was indefensible and surrendered on Nov. 13 without a struggle. Carleton, disguised in farmer’s clothing, escaped to Trois-Rivières in a boat piloted by Canadien oarsmen and, continuing his journey aboard a small vessel, arrived in Quebec City on Nov. 19.

Meanwhile, with the need to garrison Montreal and other points, coupled with the effects of sickness and expiring enlistments for many of his troops, Montgomery had only about 660 men left: 300 from the New York regiments, 200 hastily recruited Canadiens and 160 miscellaneous others. He had with him four 9- and 12-pounder cannons and six mortars, and winter clothes and provisions for Arnold’s men.

Montgomery finally joined Arnold in early December. Days later, they attempted to besiege Quebec City. But the Americans’ small guns and mortars had no effect, and the city’s cannons were of a greater calibre and range than those of their assailants.

Quebec City was key to the defence of Canada, but was almost without any regular troops. So, Carleton had to count on the militia, the Emigrants, crews from ships in harbour and untried citizen volunteers.

“I should flatter myself,” he wrote to the Earl of Dartmouth, “[that] we might hold out, till the Navigation opens next Spring, at least till a few Troops might come up the River.” But he despaired: “I think our Fate extremely doubtful.”

It was a grim assessment.

Still, safe behind the walls of the city, from where he never contemplated straying, Carleton had almost 1,800 men at his disposal including 70 regulars, 230 Highland Emigrants, 35 Royal Marines, 120 artificers, 543 Canadien militia, 330 British militia, about 395 seamen and miscellaneous other soldiers. The city of 8,000 was also well provisioned with food and firewood. And Carleton ejected all those British and Americans whom he considered disloyal.

The barely 1,000 Americans faced a daunting task. They were beset by cold, sickness (including deadly smallpox) and insufficient shelter. More than 100 muskets belonging to Arnold’s men were unusable and all troops were short on ammunition, powder and supplies. The 200 Canadiens among his ranks seemed half-hearted and some deserted.

Compounding Montgomery’s problems were the terms under which many of his men had been enrolled. Some would be free of any further service after Dec. 31 and indicated their intentions of leaving. Their departure would end the Americans’ hopes of seizing Canada’s capital. Montgomery had to assault the city as soon as possible.

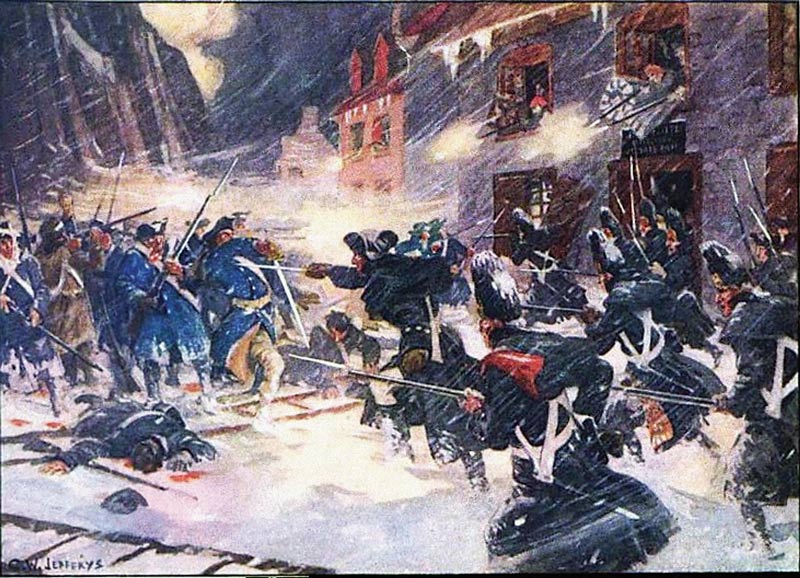

The attack was launched at 4 a.m. on Dec. 31. It was cold, windy and snowing heavily, obscuring the Americans’ advance. Montgomery organized a pincer movement along the base of Quebec’s cliffs and ramparts to seize the Lower Town prior to scaling the promontory to overcome the fortifications and attain the Upper Town. It was a very ambitious, desperate plan, as he surely knew.

One British officer rejoiced that it had been, “A glorious day for us, as compleat (sic) a little victory as ever was gained.”

Montgomery’s Canadiens launched a feint from the Plains of Abraham while he led 300 New Yorkers from the west along the river road below the commanding heights of Cap Diamant. Meanwhile, Arnold’s 600 troops swung down from the northwest along the cliffside in the Saint-Roch neighbourhood with its twisted streets and harbourside warehouses.

An artist depicts British and Canadien soldiers fighting back Americans at rue du Sault-au-Matelot, Quebec City, on Dec. 31, 1775. [Historic Collection/Alamy/KCT70B]

Disaster struck immediately. At the first road junction to the Lower Town, Montgomery’s force encountered a tall palisade barricade running from the cliffside to the water’s edge. Immediately behind it was a blockhouse manned by 30 Canadien militia and 17 British militiamen and seamen, the latter in charge of four small cannons dominating the approach.

The Americans made a hole in the palisade and some advanced toward the blockhouse, Montgomery in the lead. When the attackers were 45 metres away, the defenders unleashed concentrated grapeshot and musket fire, killing Montgomery, two officers and several other men. The Americans retreated; this part of the attack was over.

Arnold’s luck was little better. His men encountered their first barricade across the narrow rue du Sault-au-Matelot. It was defended by 30 militia and three cannons. After a stiff fight, the Americans captured the position, but Arnold was shot in the leg and evacuated. Captain Daniel Morgan assumed command and pressed on to the next barricade, which was unguarded.

While Morgan waited for the rest of his men to catch up, the British, Emigrant and Canadien forces had time to rally and properly defend the position with 200 men. The attackers were unable to scale the 3.6-metre wall with their ladders while under heavy fire and were caught in the narrow streets where they sustained heavy losses.

Canadien and British troops then sortied from the Porte du Palais, recaptured the first barricade, and caught the invaders in the rear. Fighting lasted for several hours but, realizing the hopelessness of their situation, the Americans surrendered at 10 a.m.

In total, some 400 were captured, including Morgan, and it’s likely another 100 were killed or wounded. British and Canadien casualties, on the other hand, amounted to five killed and 14 wounded. One British officer rejoiced that it had been, “A glorious day for us, as compleat (sic) a little victory as ever was gained.”

This was the American rebels’ first defeat of the Revolutionary War.

Carleton controversially elected not to sortie from Quebec and finish off his enemy, despite the British forces outnumbering the Americans 3:1.

Arnold, now in command, lost another 100 men who left after the expiration of their enlistments and had barely 700 men remaining, including the sick and his half-hearted Canadiens. He maintained light artillery fire into the town and awaited reinforcements from Montreal. They arrived steadily throughout the next several months. These new troops eventually totalled 2,500, but many weren’t in fighting condition and couldn’t mount a serious siege.

The American commander-in-chief, General George Washington, insisted that Canada be captured before the start of the navigation season. But it wasn’t to be.

On May 5, 1776, the first British warship appeared near Quebec City with reinforcements. “The news soon reached every pillow in town, people half-dressed ran down to…feast their eyes with the sight of a ship displaying the union flag,” said one British officer of the moment. The Americans retreated in near panic to Sorel, ready to ascend the Richelieu. Soon, 40 more British ships with 9,000 troops arrived in Quebec City.

Carleton’s strengthened forces advanced to Trois-Rivières. In June, the reinforced Americans renewed their offensive there, but stout British defences blunted the attack, and some 200 Americans were captured. There were still 5,000 Americans in Canada, but they continued to be ravaged by smallpox, suffered constant desertions, and the Canadiens had become far less friendly.

“Let us quit…and secure our own country before it is too late,” wrote Arnold from Montreal to General John Sullivan, the new American commander in Canada.

The invaders evacuated Sorel and Montreal, retraced their steps south along the Richelieu, and returned to their own territory. Canada had rejected the American Revolution.

Advertisement