This portrait of an unidentified Canadian First World War soldier, dated 1917 and signed by photographer C. Osborne, sold at auction for $20. It can be hard for a young person to imagine a grandparent or great-grandparent as anything but old, if they knew them at all. Wartime portraits are often their only link to a past they could only imagine. [Sparks Auctions]

About 100,000 Canadians did battle at the Somme—four divisions’ worth, plus a regiment from the Dominion of Newfoundland. For many a KIA or wizened old war veteran, it was their last, if not only, fight of the First World War.

Over the course of the three months that Canadians fought there, between August and November 1916, some 24,000 were killed or wounded, along with 2,000 Newfoundlanders, many of whom fell on July 1, the battle’s first day.

Many of the survivors went on to fight at Vimy Ridge the following April. Some survived that epic victory to fight at the Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele), where Canadians had been gassed at the second battle two years previous. And some fought through the final Hundred Days campaign that ended the war.

Grandsons, great-grandsons, nephews and grandnephews were named after Canadians killed at the Somme.

Descendants have been driven by heightened interest and curiosity

Generations later, diaries, pictures and mementoes still turn up in dusty attics and dank basements in little towns and big cities alike; old stories—snippets, really—are still told and retold long after veterans of the war, much less the Somme, have passed. The survivors, like so many before and after them, didn’t talk much.

But with landmark anniversaries and movies such as 1917, based on tales director Sam Mendes’s grandfather told him, scores of descendants have been driven by heightened interest and curiosity to seek out and explore online resources such as the Library and Archives Canada personnel records database, where 1914-1918 service records are digitally stored.

“My grandfather was at the Somme, but he wouldn’t speak about it,” says Angus Stanfield, who spent childhood summers at the family farm in Craik, Sask., learning to play the bagpipes every day from morning till night.

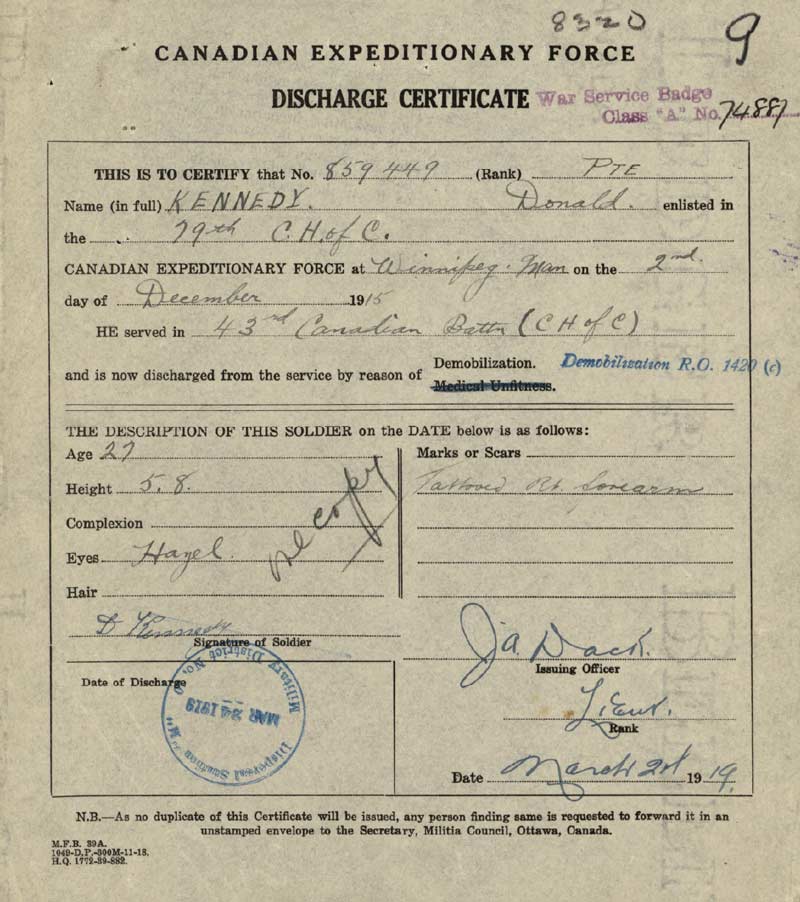

During The Great War, his grandfather was Private Donald Kennedy, a piper with Canada’s 43rd Battalion Cameron (Winnipeg) Highlanders. After surviving the Somme, he served at Vimy Ridge and Passchendaele.

Private Donald Kennedy’s discharge papers. He was a piper with Canada’s 43rd Battalion (Cameron Highlanders of Canada). [LAC]

Donald Kennedy was a quiet man. Their bond was the pipes. He had played his in battle through some of history’s most bloody affairs. Made of African blackwood, genuine ivory and mounted silver by renowned Scottish manufacturer Peter Henderson of Glasgow, they were part of a set donated to the Cameron Highlanders by former chief justice Alexander MacDonald of Winnipeg.

The days Stanfield spent with his granddad are among his fondest memories. Accompanied by his grandfather, Stanfield won first-place ribbons at three Highland Games bagpiping competitions in the summer of 1958.

“He said that there are things that no man should do to another man.”

When his grandfather died in 1969, the proud and stubborn Scotsman left his bagpipes to Stanfield, who to this day brings teenagers and the elderly alike to tears playing them at events across Canada.

He thinks of his grandfather every time he picks them up.

“He said that there are things that no man should do to another man,” recalls Stanfield, who serves as founding chairman of Cockrell House for homeless veterans in Victoria. “He and his cronies left an awful lot of themselves over there. Life was tough living with demons.”

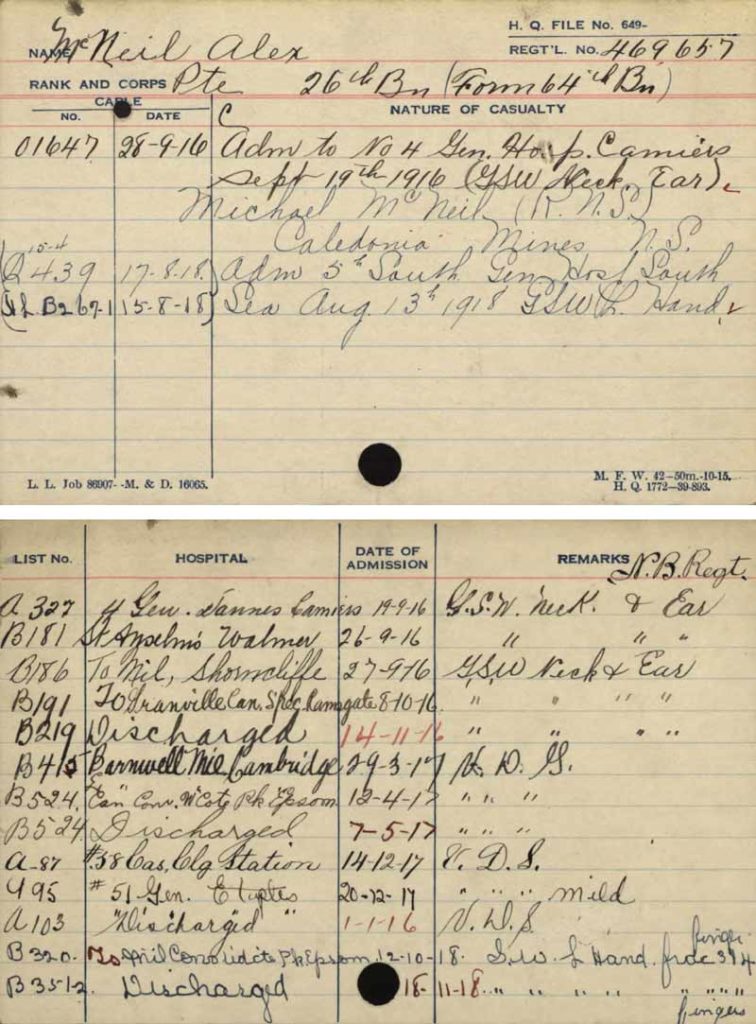

Shawn MacNeil’s grandfather Alex was serving with the 26th Battalion (New Brunswick) when he was shot at the Somme on Sept. 19, 1916.

Alex MacNeil’s right ear would always be slightly smaller than his left, and he had visible scars on his jaw, after he was shot at the Somme in September 1916. He lost his left ring finger to a bullet at Amiens in August 1918. [LAC]

“He never said much about his time in France. Quiet but very stern. Hard drinker. Loved boxing, and was very good. Between fighting the Germans and his friends, he spent a lot of time on field punishment.”

Private MacNeil’s right ear would forever be slightly smaller than his left, and he had visible scars on his jaw. He lost his left ring finger to a bullet at Amiens in August 1918.

“His death is an interesting story of his character, as well,” said his grandson. “He was downtown Glace Bay, going to cash his pension cheque. Two punks tried to rob him, but he beat them down. Unfortunately, one punched him in the chest and caused heart problems. It caught up to him later on and he passed at age 77.”

Dan Knight never knew his great uncle Francis, but the family lore surrounding him—he was one of 12 children—was enough to make him feel like he did. Frank Knight had earned a Military Medal at Mont Sorrel in June 1916, rescuing two wounded men under heavy fire.

A company sergeant-major with the 3rd Battalion (Toronto Regiment), he was killed at the Somme on Sept. 19, 1916. The battalion war diary suggests he and more than two dozen others were killed or wounded by friendly fire—a creeping barrage that came too close.

“Our own artillery firing very short causing us more casualties,” said the diary. “CSM Knight wounded. About 50 casualties to date 30 of which have been from our own shell fire.”

Knight died later that day and now lies buried in the Warloy-Baillon Communal Cemetery Extension.

“My late father, William Francis Knight, was named after him,” said Dan Knight.

His brother was killed at Passchendaele on Nov. 8, 1917.

Jim Little of Turner Valley, Alta., never knew his grandfather, Charles Edward Little, who served with the 58th Battalion out of Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ont.

He was a sergeant-major fighting at Ancre Heights on Oct. 8, 1916, when his battalion was all but wiped out. C.E. Little survived and spent 13 months on or near the Western Front until heart problems forced the newly minted lieutenant out of officer training in England and home to Canada.

His brother—Jim’s great uncle—Sergeant William Little was killed at Passchendaele on Nov. 8, 1917, while serving with the 15th Battalion (48th Highlanders of Canada).

Jim published a biography of his grandfather, Searching For Connection—The C.E. Little Story, in November 2019.

“The grandfather I never knew, Lieut. C.E. Little, died 40 years after the Battle of the Somme, just before his future grandchildren began to make their appearance,” said Jim Little. “My dad always kept his father’s formal picture hanging in his home, although he rarely spoke of him. Another 60 years after my grandfather’s death, my dad also passed, a beloved grandfather and great grandfather.

“Now it’s my turn as a grandfather to take ‘the torch and hold it high,’ as John McCrae said. The research, writing and publication of [his biography] will help ensure his legacy lives on.”

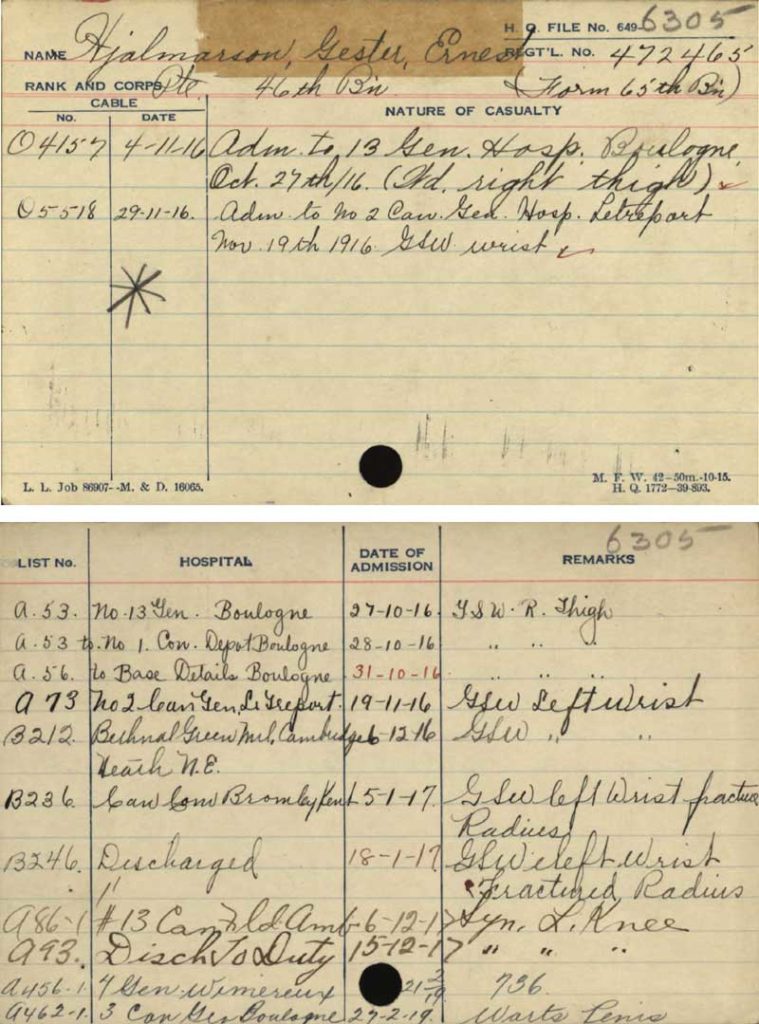

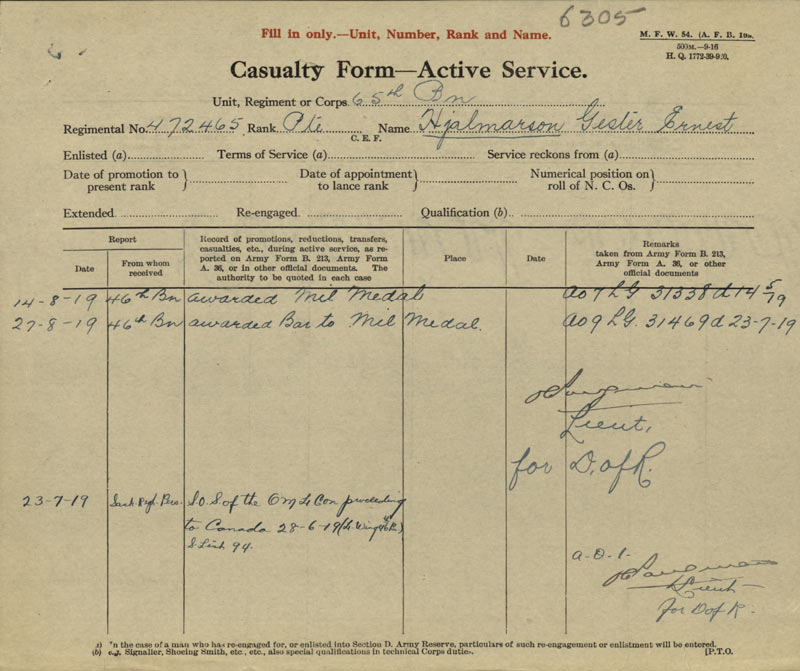

Eric Hjalmarson’s grandfather Gester served in both world wars, first enlisting with the 46th Battalion (South Saskatchewan) on Oct. 1, 1915, in Saskatoon.

He had the unenviable distinction of being wounded twice: shot through the right thigh two months after he landed in France, then shot through the right wrist eight days after he rejoined his unit on Nov. 11, 1916.

Gester Hjalmarson was shot through the right thigh two months after he landed in France, then shot through the right wrist on Nov. 11, 1916, eight days after he rejoined his unit at the Somme. [LAC]

Hjalmarson was promoted to corporal when he returned to action the following May, earning a Military Medal at Arras in October 1918 and a bar for actions at Cambrai. [LAC]

Eric Hjalmarson joined the army at age 50, the oldest graduate ever of the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry battle school. He finished in the Top 10 among 32 graduates.

Eugène Cornect was out mowing hay in Cape St. George, Nfld., in September 1914 when he saw a recruitment ship offshore. The 21-year-old became Soldier No. 429 of the Newfoundland Regiment’s First 500, a fighting francophone in the Blue Puttees.

“He wasn’t fighting for the British—well, in a way—but he was for Newfoundland,” his daughter Marina Cornect told CBC in 2016.

“He knew if he stayed immobile, he may be able to survive.”

Eugène had survived Gallipoli and dysentery by the time he arrived at Beaumont-Hamel as a scout. He was one of the first soldiers over the top on July 1, 1916.

He was hit by shrapnel in his ankle early on and spent the next 20 hours among the dead. “He just laid there and stayed there, because he knew if he stayed immobile, he may be able to survive.”

He began crawling back to safety at dawn the next day, meeting a wounded German in the mud along the way. They “just…stared at each other, he said, and [they] shook hands and then said goodbye.”

Eugène’s refrain over the years was “we were just fighting for the country, not against the man.”

He eventually lost the leg to his wounds; the stresses of battle lingered the rest of his days. His children described him as “a bit of a pest when he was drinking.”

He passed on opportunities to revisit the battlefield that changed his life. But Marina embarked on a pilgrimage to Beaumont-Hamel with her sister in 2006.

“I came home and for weeks after all I saw was white crosses and poppies.”

Michael Creagen of Halifax never met his Irish-Canadian grandfather, Henry, who was born in Belfast and signed up in Toronto on June 8, 1915. He spent the Somme in a prisoner of war camp, an ordeal that ultimately cost him his life.

Serving with the 4th Battalion, Canadian Mounted Rifles, he was captured after a five-hour bombardment and three underground mine blasts near Ypres on June 2, 1916.

“The trenches were tilled flat by the rain of steel and high losses,” said the battalion war diary. “Some 71 wounded made it back, 91 killed in total in addition to the final figure of 350 taken PoW (13 of whom subsequently died after being taken captive), meant there was little (albeit ferocious) resistance against the advancing Württemberg troops.

“The enemy had gained some 300 to 700 yards [275 to 640 metres] along a varied front, but subsequently failed to consolidate their gains.”

The 4th moved to the Somme in September. While his brothers in arms were taking Courcelette and Regina Trench, Henry (Harry) Creagen was working forced labour in a German coal mine. He escaped three times in two years, only to be caught each time.

“The third time they made him stand outside in the rain for 24 hours to teach him a lesson,” said his grandson, relating stories passed down by his dad. “He spent the next few months in hospital under the care of a German doctor. My grandpa didn’t like the Germans but he always spoke highly of the doctor who helped him.”

Creagen was plagued by cardiovascular issues until he died in 1928.

—-

Canada and the Brutal Battles of the Somme, the latest in the Canada’s Ultimate Story series, is on newsstands now. You can also order it for delivery to your home from the Canada’s Ultimate Story website.

Advertisement