Lieutenant Francis Henry (Frank) Hemsley, a Prince Albert, Sask., farmer born in England, was killed in 1917 at the Battle of Hill 70.

[DND]

There were fragments of a gas mask and a helmet, a pair of badly damaged boots and, most important, several buttons clearly marked “16th Battalion, Canadian Scottish Regiment.”

The 16th fought a few kilometres away at Hill 70 in August 1917. The remains of multiple Canadians killed in the battle have been discovered at Vendin-le-Vieil and identified in recent years, including other members of the 16th.

Just four months after suffering 333 casualties at Vimy Ridge, the battalion took 257, 62 of them killed in action, in three days at Hill 70, a strategic feature where the Canadian Corps took on five divisions of the German 6th Army.

The attack near the Belgian border aimed to inflict casualties, render Germany’s hold on the nearby coal-mining town of Lens untenable and draw enemy resources away from the Ypres Salient, 60 kilometres to the north.

It was there, at Passchendaele in Flanders, where Canadian troops would strike the final blows in the salient’s third major battle in less than three years (there would be five by the time the war ended; the 16th fought the second).

A set of buttons embossed with the 16th Battalion, Canadian Scottish Regiment, was found with unidentified remains at a construction site in northern France in August 2012.

[DND]

Coming off his seminal victory at Vimy, Lieutenant-General Arthur Currie—who had led the 16th before he rose through the ranks to command the Canadian Corps—had currency with his British superiors.

He took stock of the situation at Lens and concluded that his artillery would have a hard time smashing the well-camouflaged German defences, leaving the infantry to face intolerable casualties.

So, Currie persuaded the British high commander, Field Marshal Douglas Haig, that he should take the high ground north of the town first and set up defensive positions along its slopes to cut down German counterattacks.

A methodical planner, many of whose methods were ahead of their time, Currie had his soldiers train extensively for the battle, rehearsing their individual roles on similar terrain, as they did before Vimy. Artillery strikes and trench raids followed, the latter on positions south of the town to mislead the enemy.

Canadian soldiers recharge at a soup kitchen near the front line during the Battle of Hill 70 in August 1917.

[LAC/PA001596]

The Germans had held Hill 70 since 1914. True to Currie’s expectations, the defenders were tenacious, dug-in and well concealed.

Canadian and British guns fired almost 800,000 shells in previous days, killing, wounding and wearing down the German defenders, cutting barbed wire, disabling artillery emplacements, hampering communications and collapsing trenches.

Royal Engineers launched a covering smokescreen just before the attackers began to move.

“Oil drums were sent careering over at zero hour with a sound like the roar of the shells from the seventeen-inch guns,” recorded the 16th Battalion history, published in 1932. “When they struck the enemy’s trenches they burst into a flood of fire.”

The Canadians fired and faced millions of machine-gun rounds during the fighting.

Choking chlorine gas had been first used against Allied soldiers at the Second Battle of Ypres in the spring of 1915. Now new forms of poison came via the blistering agent sulphur mustard—soon-to-be known notoriously as mustard gas, which caused chemical burns to the skin, lungs and eyes.

“When passing through the Canadian gun line in the Loos hollow, the members of the Battalion saw rows of men naked to the waist, writhing on the ground and gasping for breath,” said the battalion history. “They were the casualties of the first German mustard gas attack (on the Canadians), and had been caught when serving their guns the previous night in response to the S.O.S. calls of the infantry.”

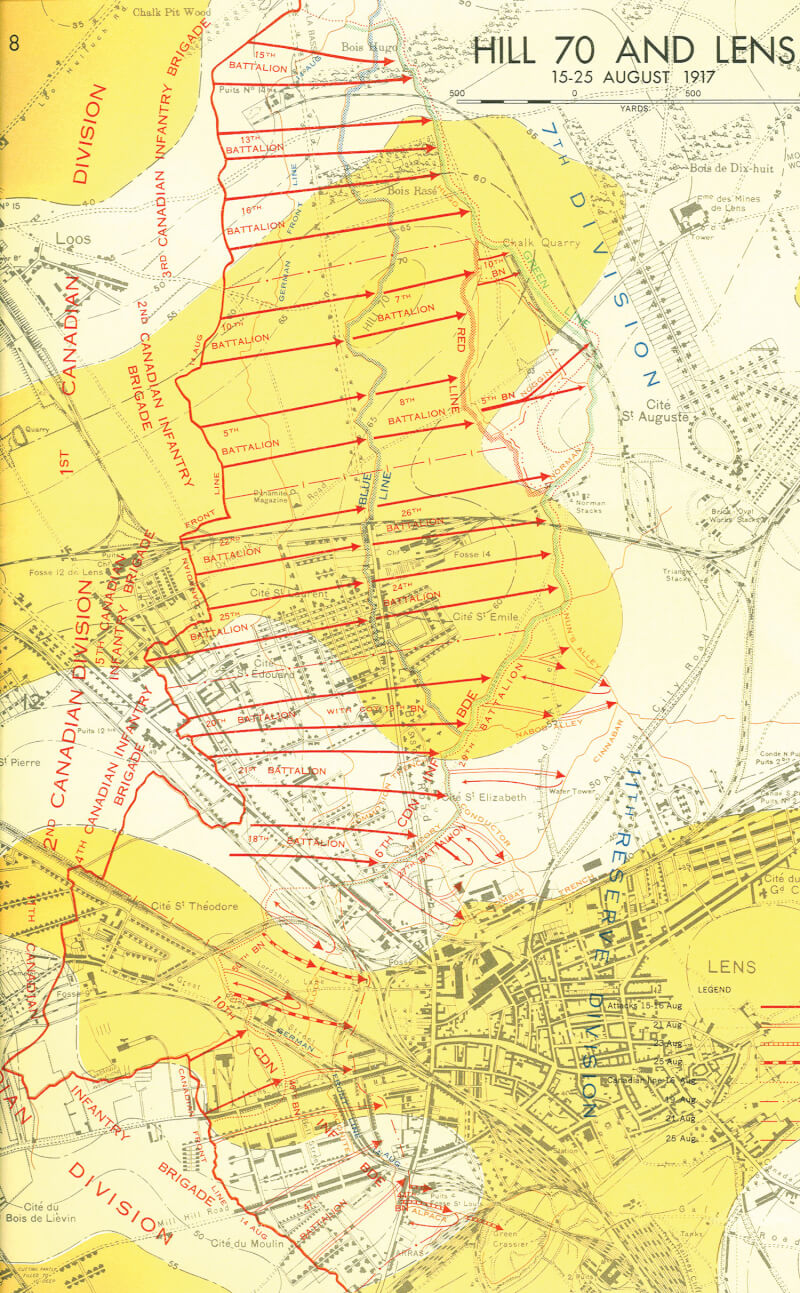

A battle map showing Hill 70 and Lens, to the south. The 16th Battalion is third from the top in the line of battle.

[DND]

The Canadians quickly seized most of their objectives on the slopes of Hill 70, but then endured 21 German counterattacks. The corps suffered 1,877 killed and more than 7,000 wounded or missing in action at Hill 70.

Though Lens would not fall, the Canadians would hold their high-ground positions for the rest of the war.

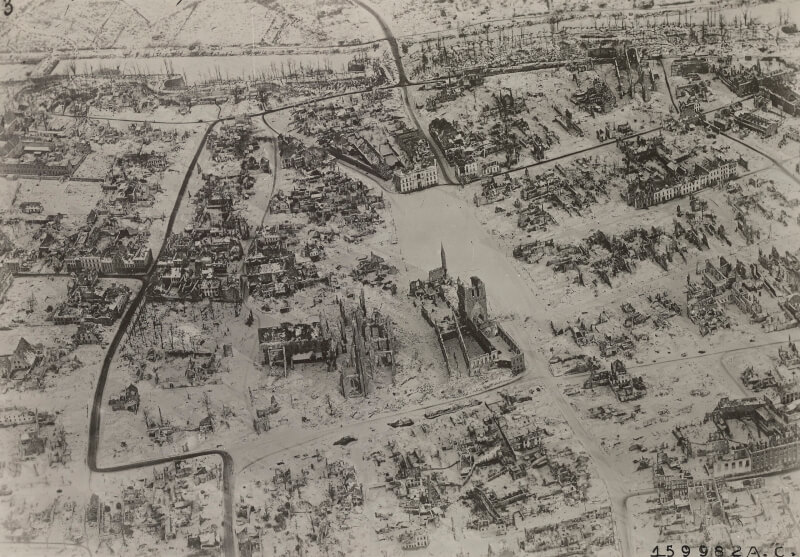

After three major battles, Ypres in the winter of 1917 was a total ruin. There would be two more battles in the Ypres Salient before the war was over.

[Wikimedia]

Soon after he was discovered, the Canadian military’s Casualty Identification Review Board went to work. With help from the Canadian War Museum and the Canadian Museum of History, its staff tapped historical, genealogical, anthropological, archeological and, with the co-operation of prospective family, DNA expertise and analysis.

By February 2024, they confirmed the remains as those of Lieutenant Francis Henry (Frank) Hemsley, a Prince Albert, Sask., farmer and one of seven children born to Alexander and Ellen Hemsley of Ealing, a district in West London, England. The investigators announced their conclusions on March 14.

Hemsley had served as a trooper in the Boer War with the 35th Squadron, 11th Battalion, Imperial Yeomanry, in 1900-1901.

He immigrated to Canada with wife Adina and their two children in 1911, where he joined the 52nd Prince Albert Volunteers militia regiment before enlisting with the Canadian Expeditionary Force in Winnipeg in February 1916. He was 35 years.

Hemsley qualified and briefly served as a Lewis gun instructor before he was transferred to the gutted 16th just after Vimy in April 1917. He joined the unit in France in May.

Attacking to the skirls of bagpipes, the Canadians achieved their objectives early on the first day of battle at Hill 70 but, as the battalion history notes, “for the attacking troops the aftermath, the punishment, had still to come.”

By early afternoon, the enemy had pinpointed the Canadian positions on the crest of the hill. “He began to subject them to a steady bombardment, which he kept up with few breaks until the early morning of the next day, the 16th,” it said.

“Throughout the day of the 16th and the night 16th/17th, the enemy shelled continuously…. The Battalion casualties for the actual assault were light, but the after-shelling exacted its toll.”

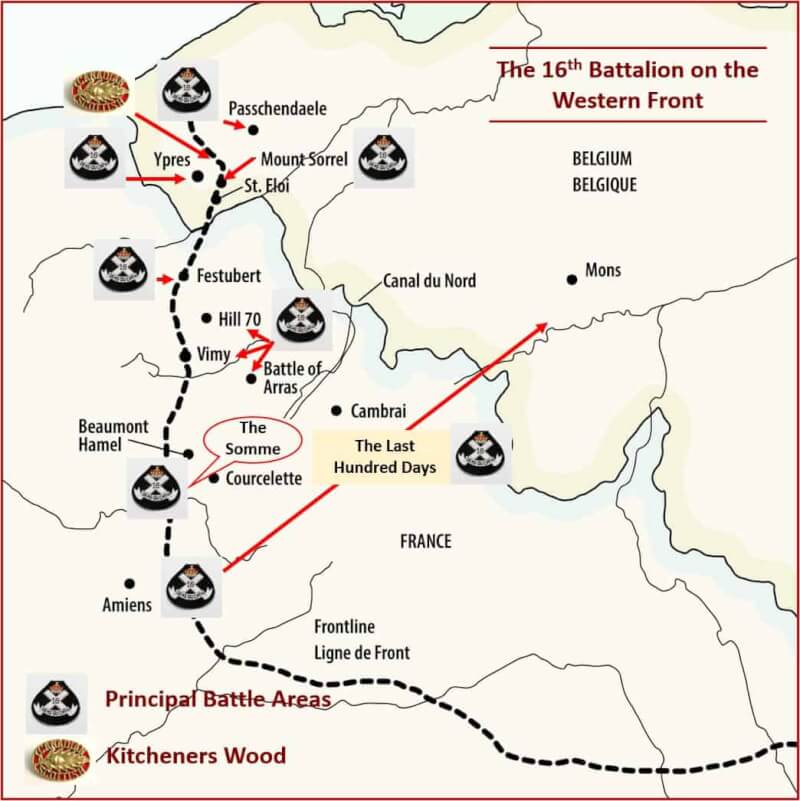

The 16th was active throughout the Western Front during the course of the First World War.

[cscotrmuseum]

“The relief of the Battalion which was taking place that night was greatly hampered,” said the history. “It was four a.m., the 17th, before it was completed, and the Commanding Officer and Battalion Headquarters, a group of tired looking, mud-stained men, headed by the pipe major, were able to return to [the battalion HQ at] Mazingarbe.

“The pipe major played ceaselessly the whole way,” it continued. “When finally the little group reached the village bounds, the strains of the bagpipes attracted the attention of the company men who had reached billets some time before.

“They looked around and, discovering it was the Colonel returning from the field of victory, rushed out into the street, many of them without boots or puttees and some without kilts. They greeted the party with cheer upon cheer and, in a band, escorted the procession to Battalion Headquarters.”

As is the practice, Hemsley’s name will remain on the Canadian National Vimy Memorial alongside those of 11,284 other Canadian soldiers killed in France during the First World War with no known grave.

The Casualty Identification Program has identified the remains of 36 Canadians since its inception in 2007. In 2019, it officially took on the additional responsibility of identifying the graves of Canadian service members buried as unknowns. It has since identified 12.

It is currently conducting 42 investigations involving remains and 39 involving graves.

Advertisement