Event co-ordinator John Jewitt, an Anishinaabe from Nipissing First Nation in northeastern Ontario, smudges Canadian Ranger Sergeant McLeod McKay during a ceremony at the National Aboriginal Veterans Monument in Ottawa on June 21, 2022.

[Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

The military was a lumbering organization, far from progressive and slow to change. Being anything other than white was perceived as a potential impediment to progress in the Canadian Forces—and worse.

Uniformed Indigenous Peoples were subjected to hazing, insults and other harassment from their fellow soldiers. Stevens just wanted a military career.

“I was ashamed of my own culture,” he said.

That, in spite of a Canadian military history that includes household names such as Shawnee Chief Tecumseh and his First Nations confederacy who fought alongside Canadian and British soldiers during the War of 1812; Francis Pegahmagabow of the Wasauksing First Nation, considered the most deadly sniper of the First World War; and decorated Second World and Korean wars veteran Tommy Prince of Brokenhead Ojibway Nation, who overcame repeated rejections by recruiters before becoming a paratrooper and decorated war hero.

Canadian military badges are rife with Indigenous iconography—arrowheads adorn the uniforms of 2 Canadian Mechanized Brigade Group of Petawawa, Ont.; 31 Canadian Brigade Group garrisoned in London, Ont.; and Canadian special forces.

The thunderbird, an Indigenous spirit creature resembling an eagle, is the emblem of the CAF military police. A common symbol among Pacific northwest First Nations, it’s regarded as an honourable bird and a good spirit dedicated to helping man.

Retired sergeant John Jewitt is a 30-year military veteran who served in Somalia and on two life-changing tours in Cyprus, where he first deployed at 18 years old. He’s also an Anishinaabe from Nipissing and he co-ordinated National Indigenous Peoples Day events in Ottawa.

In Indigenous culture, he said, the warriors were always the defenders and the protectors. They were the “important people” and, to this day, they are front-and-centre at traditional Indigenous events such as powwows.

But in the Canadian military, it used to be that Indigenous personnel would try to hide their heritage for fear they would be overlooked for promotions and other advancements if they didn’t. Jewitt says he overcame his own obstacles with help from a broad diversity of friends. Now, he says, times are changing.

“More people are wearing their Indigenous heritage with pride.”

That’s the case for Stevens, who’s now Indigenous adviser to the Chaplain General of the Canadian Armed Forces. He wears his braids long—“proudly”—and stands tall as he bears the military’s eagle staff at events like the June 21 ceremony honoring Indigenous veterans at the National Aboriginal Veterans Monument in Ottawa.

Stevens was also at a National Indigenous Peoples Day ceremony at Beechwood, site of the National Military Cemetery of the Canadian Armed Forces, where Indigenous spiritual symbols were officially recognized alongside the Christian cross, the Jewish Star of David, Islam’s Crescent Moon and seven other religious and spiritual symbols to adorn its headstones.

Stevens acknowledged society has come a long way and the general populace is more aware of what Indigenous Canadians have endured over the years, but he said he and other Indigenous Peoples are looking for more concrete action.

“It’s not perfect by any means,” he said. “But more conversations are taking place now, and that’s a good thing.”

CPO2 Patrick Stevens of Nipissing First Nation (left), Indigenous adviser to the Chaplain General of the Canadian Armed Forces, and RCMP Staff-Sergeant Jeff Paulette of Membertou First Nation in Quebec, stand at the National Aboriginal Veterans Monument in Ottawa bearing the eagle staffs of their respective services.

[Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

A Mohawk Warrior attends a ceremony at the National Aboriginal Veterans Monument in Ottawa on June 21, 2022.

[Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

Canadian Rangers in their distinctive red caps and hoodies take in the scene at the National Aboriginal Veterans Monument during National Indigenous Peoples Day in Ottawa.[Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

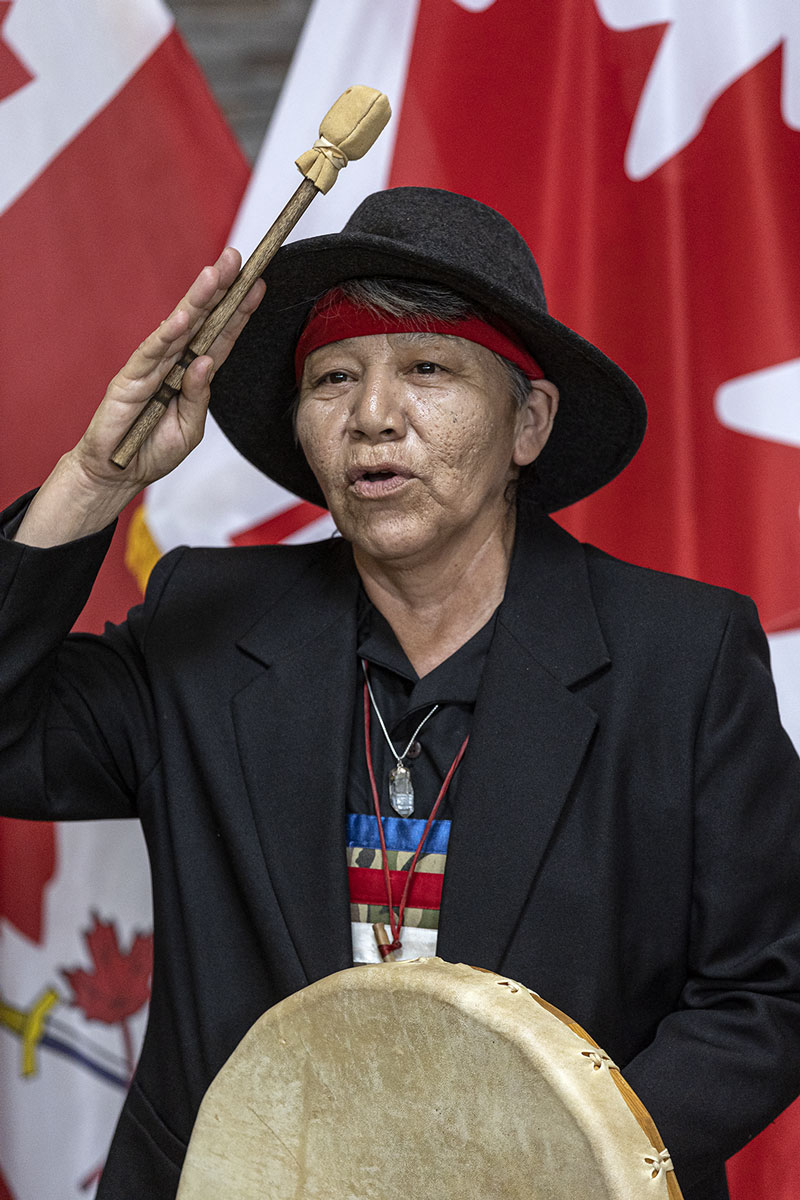

Indigenous drummers perform during National Indigenous Peoples Day in Ottawa. [Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

Participants and onlookers watch the ceremony marking National Indigenous Peoples Day at the National Aboriginal Veterans Monument in Ottawa on June 21, 2022. [Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

A Canadian Ranger ponders the National Aboriginal Veterans Monument during a ceremony in Ottawa on June 21, 2022.

[Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

CPO2 Patrick Stevens of Nipissing First Nation, Indigenous adviser to the Chaplain General of the Canadian Armed Forces, stands at the National Aboriginal Veterans Monument in Ottawa bearing the military’s eagle staff. [Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

RCMP Staff-Sergeant Jeff Paulette of Membertou First Nation in Quebec, stands at the National Aboriginal Veterans Monument in Ottawa bearing the national police service’s eagle staff. [Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

Gary Dore, an Indigenous peacekeeping veteran (left), along with Korean War vets Bill Black, Gordon Gallant and George Guertin, participate in the National Indigenous Peoples Day ceremony at the National Aboriginal Veterans Monument in Ottawa.

[Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

The Royal Canadian Legion’s grand president, retired admiral Larry Murray (left), and Executive Director Steven Clark placed a wreath at the National Aboriginal Veterans Monument on National Indigenous People’s Day in Ottawa. [Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

Métis veteran Robert Thibeau, a former paratrooper and retired infantry captain, places a wreath at the National Aboriginal Veterans Monument on behalf of the Aboriginal Veterans Autochtones. Thibeau is the group’s president and a founding member.

[Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

The National Aboriginal Veterans Monument is adorned with wreaths after the National Indigenous Peoples Day ceremony in Ottawa.

[Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

Many of the badges on the rain-soaked headstones at the National Military Cemetery of the Canadian Forces at Beechwood in Ottawa bear Indigenous iconography. Beechwood has adopted Indigenous spiritual symbols for military headstones.

[Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

The National Military Cemetery of the Canadian Forces at Beechwood in Ottawa bears Indigenous iconography.

[Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

2nd Mechanized Brigade out of Petawawa, Ont., and 31st Canadian Brigade Group garrisoned in London, Ont., are among many Canadian military units whose badges borrow from Indigenous culture. [Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

Sacred fire keeper Peter Decontie, an Algonquin from Kitigan Zibi, conducts a ceremony over the adoption of Indigenous symbols at the National Military Cemetery at Beechwood in Ottawa. [Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

Sacred fire keeper Peter Decontie smudges the Indigenous symbols adopted by the National Military Cemetery at Beechwood in Ottawa. [Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

CPO2 Patrick Stevens of Nipissing First Nation stands with the eagle staff of the CAF as Métis sisters Kailee (left) and Brianna Quesnel conduct a healing jingle dance over the newly adopted Indigenous spiritual symbols at the National Military Cemetery in Ottawa. Their uncle, who died last fall, was the first veteran to receive an Indigenous spiritual symbol on his tombstone.

[Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

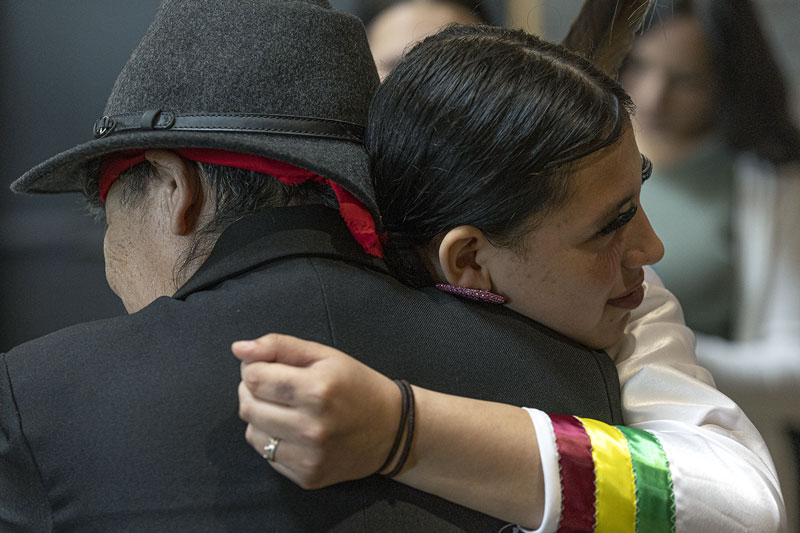

Métis sisters Kailee (left) and Brianna Quesnel hug after the healing jingle dance over the newly adopted Indigenous symbols at the National Military Cemetery in Ottawa. [Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

An eagle feather adorns a granite stone bearing two Indigenous spiritual symbols—the First Nations medicine wheel and the Métis infinity symbol, chosen after consultations between military and Indigenous representatives, bringing to 11 the number of spiritual symbols adorning headstones at the National Military Cemetery. An Inuit symbol has yet to be chosen as their approach to spirituality and grief is different than that of First Nations and Métis. [Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

Grandmother Alma Mann Scott of the Ojibwa Sagkeeng First Nation sings a bear song over the newly adopted Indigenous spiritual symbols at the National Military Cemetery. [Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

Grandmother Alma Mann Scott of the Ojibwa Sagkeeng First Nation salutes attendees during an Indigenous ceremony at the National Military Cemetery on June 21, 2022. [Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

Jingle dancer Kailee Quesnel hugs Grandmother Alma Mann Scott of the Ojibwa Sagkeeng First Nation after a ceremony at the National Military Cemetery on June 22, 2022. Scott, an Indigenous Elder, helped the family through difficult times after an uncle died last year.[Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

Children touch the granite stone bearing the Indigenous spiritual symbols adopted by the National Military Cemetery in Ottawa.

[Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

Advertisement