Sitting in the coldest, most vulnerable spot on seven-man Halifax or Lancaster bombers, tail gunner Sergeant Ronald Moyes, the 18-year-old son of an immigrant farmer from Coquitlam, B.C., would pick them up at about 550 metres out.

Tracking the incoming enemy with his four .303-calibre machine guns on a single trigger, their ammunition belts running the length of the aircraft, Moyes would call out over the radio to the skipper up front, “fighter, corkscrew starboard” or “fighter, corkscrew port.”

Flight-Lieutenant Don Walkley, a cool-headed 21-year-old from Pincher Creek, Alta., would then crank the plane over and into a near-vertical spiraling dive.

“By that time, your eyebrows are up to here and you’re coming off the seat,” Moyes, now 97, told Legion Magazine in a recent interview. “And you’re trying to keep your eye on the lead fighter.

Moyes had 10,000 rounds to work with, or about two minutes and 10 seconds of firing time—much more than the average fighter pilot, but with a lot less punch.

And shooting in high G-forces—both positive and negative—out of the cramped turret of a corkscrewing aircraft, its Perspex removed for better visibility, was a challenge. Armed with cannons, the smaller, more nimble German planes would make a high-speed pass and, in seconds, they would be gone.

Moyes never got one, and one never got him during his 30 missions over wartime Europe—five- to seven-hour round trips to some of Germany’s prime objectives: the port and shipbuilding yards at Wilhelmshaven, the railyards and industrial plants at Chemnitz, and the very hearts and minds of all Germans as they hit the symbolic Nazi city of Nuremburg, site of the mass rallies that propelled Hitler to power, and to war. They even hit Hitler’s retreat at Berchtesgaden.

For the majority of those who survived the drop, it was just a matter of time before they were captured.

While Walkley’s evasive tactics proved successful against the Luftwaffe night fighters, avoiding flak from the German anti-aircraft shells exploding all around them was near-impossible on the four- to five-minute straight-and-level final approaches to their targets. Their aircraft was often hit too many times to count the holes.

“It sounded like somebody was throwing rocks at us,” said Moyes, describing a nighttime sky lit with criss-crossing searchlights and the momentary concern as shockwaves from the AA explosions buffeted their 17-tonne aircraft.

Seated at the tail and surrounded by hundreds of planes above and below, Moyes had a box-seat view as numbers of the great four-engine bombers—among the biggest in the Allied arsenal—tumbled downward in flames, their crew streaming from within in ones and twos or, more often, not.

At Nuremburg, Bomber Command lost 96 and 29 aircraft during two large raids in early 1945, their casualties totalling some 875 crew.

Like vultures to the feast, the fighters above would be waiting as the bombers cleared the flak and headed home. The German flyers would keep a sharp eye out for stragglers and pick them off as the lumbering bombers made their way out of the target area and headed for the coast.

It wasn’t until early 1944 that long-range fighter escorts were able to accompany bombers all the way to Germany and back, but they were typically provided to the American daylight raiders, not the British and Commonwealth night attackers.

For the bomber crews, the English Channel marked relative sanctuary, but there always remained uncertainty as they approached their base whether their landing gear was still functional. They would never know for certain until Walkley laid all three points of their plane down on terra firma.

After many a sleep, Moyes would awaken to empty cots in the enlisted barracks. They wouldn’t know for days whether their missing occupants had been shot down or diverted to another base, which was often the case for crippled aircraft.

It’s credibly estimated that between 22,700 and 25,000 people were killed, the vast majority of them civilians and refugees.

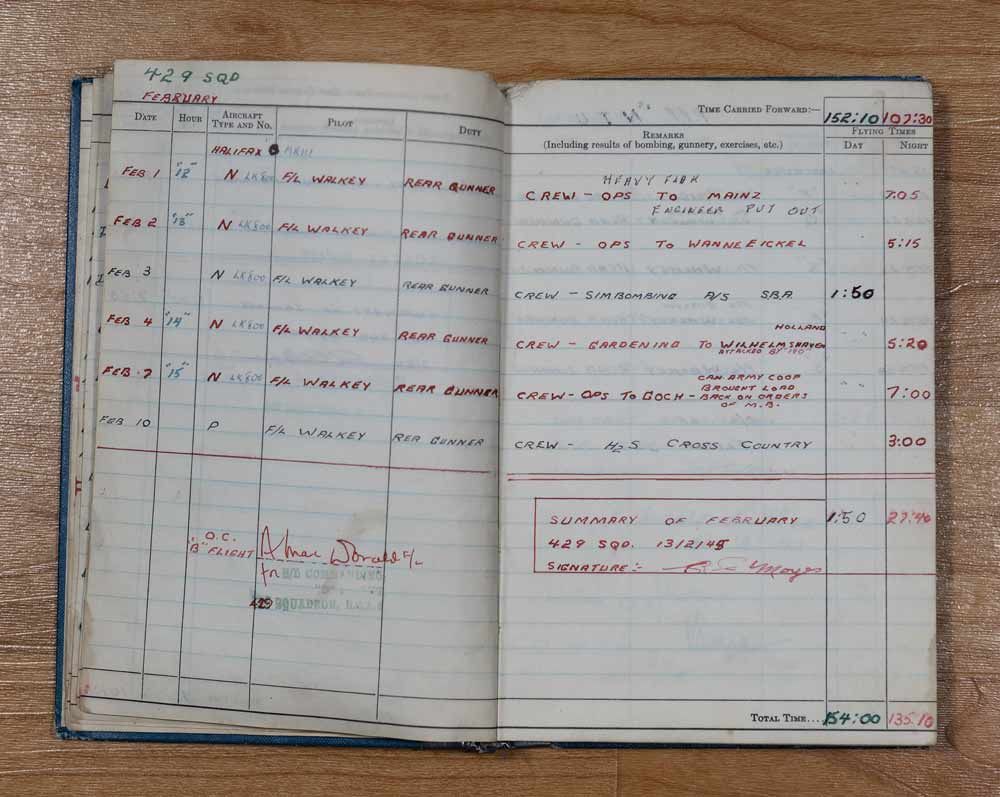

Moyes signed up at age 17 and headed overseas in May 1944. He joined 429 Squadron at Royal Air Force Station Leeming, just north of the English city of York. They were flying Halifax Mk III bombers on nighttime missions to the continent.

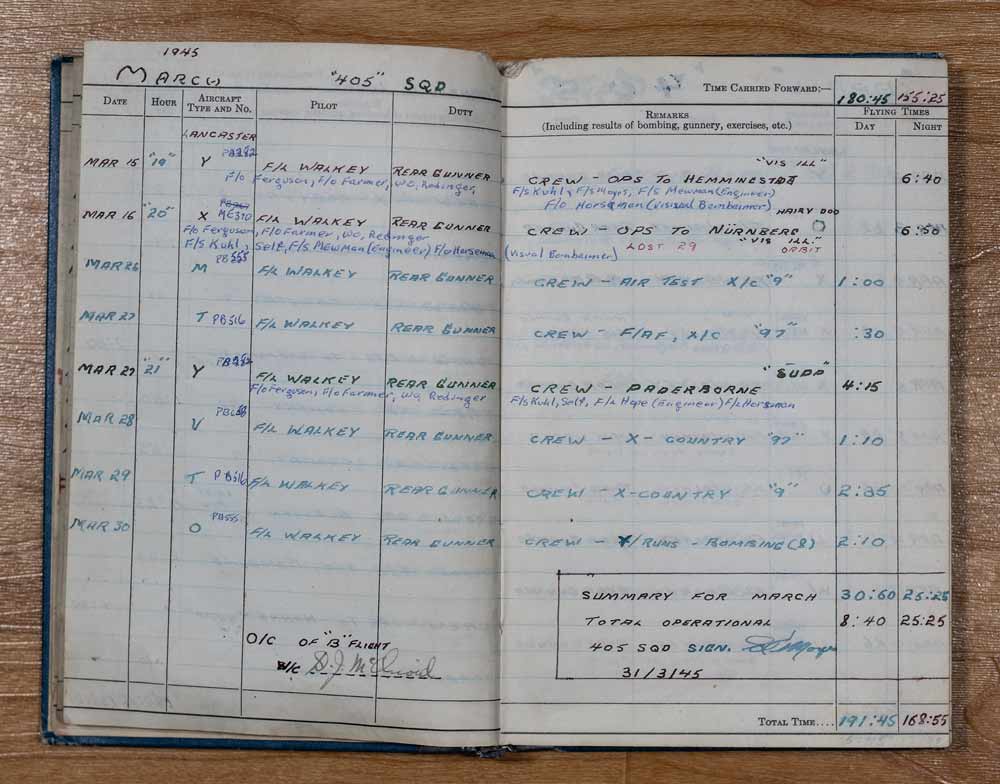

He and the rest of his crew would later transfer to 405 Pathfinder Squadron, where they had the unenviable job of venturing ahead of the attack formations and marking the targets.

The Americans were conducting daylight raids, convinced that with the aid of the sun and Norden bombsights, they could administer precision strikes on high-value targets and avoid excessive civilian casualties.

Air Chief Marshal Arthur (Bomber) Harris, architect of RAF Bomber Command’s nighttime campaign, which included Canadian and other Commonwealth crews, had no such qualms. He opted instead to prioritize his crews’ lives above all and essentially saturate their target areas with bombs.

Frustrated in their daylight efforts and losing planes and men at an alarming rate, the Americans would ultimately follow Harris’s lead and abandon any notion of precision strikes, particularly in the Pacific theatre, where they turned Japanese cities into mass infernos using napalm—a sticky, gasoline-based substance—for the first time, to devastating effect.

Between Feb. 13 and 15, 1945, 772 RAF bombers and 527 United States Army Air Force aircraft dropped more than 3,500 tonnes of high-explosive bombs and incendiary devices on the German city of Dresden, creating a firestorm. It’s credibly estimated that between 22,700 and 25,000 people were killed, the vast majority of them civilians and refugees—as well as some Allied PoWs.

For the bomber crews, it came down to a simple matter of getting the job done and getting out alive. Life expectancy for new recruits was two weeks.

Of every 100 airmen who graduated from an operational training unit, 61 would die before completing their requisite 30 missions, 12 would end up PoWs, three would be wounded and unable to fly again and only one would successfully escape.

According to the Bomber Command Museum of Canada, 55,573 of 120,000 Bomber Command crewmen were dead by war’s end, making for a 53 per cent survival rate. The Royal Canadian Air Force says some 10,600 of those killed in action were Canadian.

“Mynarski moved to the escape hatch and there, as a last gesture, turned towards the trapped gunner, stood to attention in his flaming clothing, and saluted before jumping.”

That involved thigh-high woolen stockings, a long wool turtleneck sweater, a battle dress uniform with a whistle attached in case they ditched, a once-piece electrically heated coverall, then an inch-thick padded “teddy-bear suit” followed by his flight suit, its pockets filled with escape rations. He then put on his leather flying boots, Mae West life jacket and parachute harness.

Most of the tail gunners were issued chest-pack parachutes, which they wouldn’t wear until they needed them. They were stored behind the turret where they could retrieve them if things went south. Moyes, at five-foot-six an ideal size for the tiny confines of a rear turret, preferred the same seat pack used by fighter pilots and, as an added bonus, it proved an ideal booster seat for the diminutive machine-gunner.

Finally, he donned his helmet, oxygen mask and gloves—three pairs of them, starting with a thin pair of chamois gloves, then electrically heated gloves and, finally, leather gauntlets.

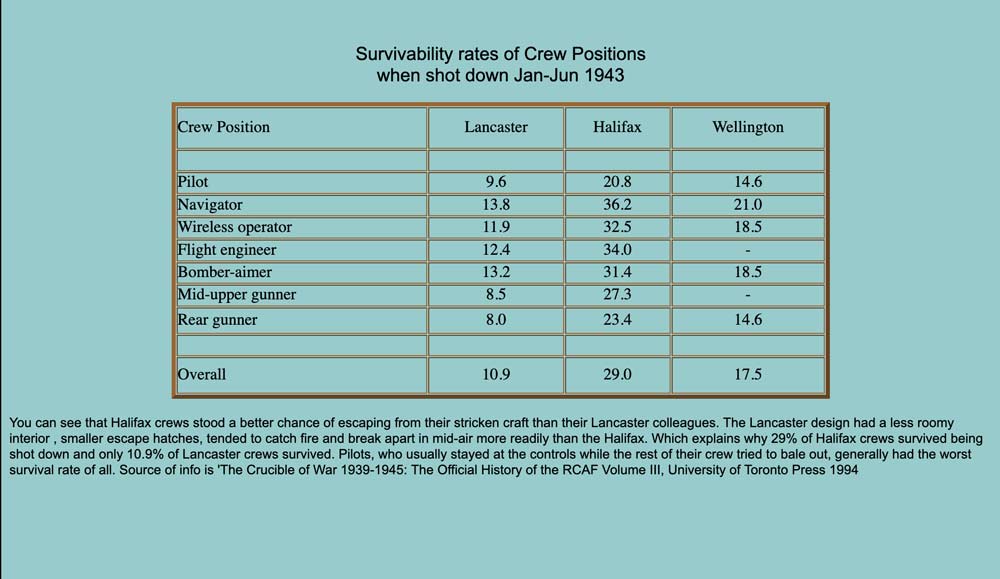

Cramped, even for Moyes, the rear turret was for many a death trap.

Beyond the fact the position was the most exposed on the aircraft, the turret doors were behind the gunner. The turret was therefore notoriously hard to get out of, requiring the gunner to rotate it 180 degrees before he could exit.

The hydraulics that enabled the rotation, however, could often be damaged and rendered inoperable in an emergency. Even when they did work, the tail gunner had to climb over the tail structure to reach the escape hatch.

All of which meant inordinately high mortality among tail gunners—of the 55,573 Bomber Command crew killed in the Second World War, some 22,000 were tail gunners, or almost 40 per cent of the KIAs in a crew of which they comprised 14 per cent.

The rest of the crew of Lancaster VR-A of 419 Squadron, RCAF, had bailed out on June 12, 1944, when Pilot Officer Andrew Charles Mynarski, a mid-upper gunner, earned a posthumous Victoria Cross trying to save his plane’s tail gunner, Sergeant Pat Brophy, as their aircraft went down over France.“As P/O Mynarski moved towards the escape hatch he saw that the rear gunner could not leave his turret, which was rendered immovable when the hydraulic gear was put out of action by the failure of the port engine,” his citation said.

“The Pilot Officer unhesitatingly moved back through the flames and tried to release the gunner, although his own clothing and parachute were on fire. All his efforts to move the turret and free his comrade were in vain, and eventually the gunner told him to try to save his own life. Reluctantly P/O Mynarski moved to the escape hatch and there, as a last gesture, turned towards the trapped gunner, stood to attention in his flaming clothing, and saluted before jumping.”

Incredibly, Brophy survived the crash after he was blown safely away from the plane by exploding ordnance when it hit the ground. Mynarski survived the jump, only to die from his burns the following day.

In fact, the burst took out the plane’s starboard outer engine.

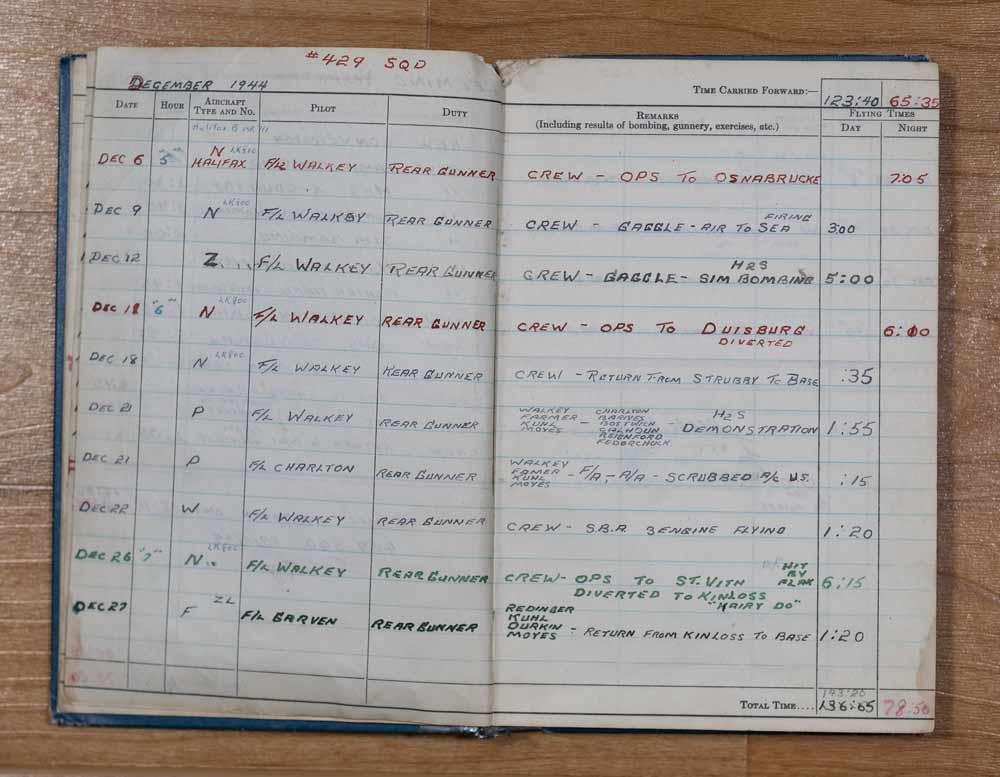

Moyes flew 18 of his 30 missions at age 18. His seventh, to take out transportation and communications infrastructure around the occupied Belgian village of St. Vith on Dec. 26, 1944, was among the hairiest for Moyes and his crewmates.

The Battle of the Bulge was peaking. The predominantly American forces had been under siege around Bastogne since Dec. 16, under-supplied and unsupported due to relentless fog and heavy snow. The weather finally broke on Christmas Day, allowing aircraft to resupply the cold and desperate troops.

As the bomber formation approached St. Vith, 45 kilometres northeast of Bastogne, they encountered heavy flak and their aircraft, AL-N (Tail No. LK800), was nearly shot down.

“HAIRY DO,” Moyes wrote in his logbook. “HIT BY FLAK.”

In fact, the burst took out the plane’s starboard outer engine. “On the way home, we found we still had two 500-pound bombs on our port wing, which we tried to drop over the English Channel, but they wouldn’t release,” he said.

They were behind the formation by this point and Leeming was fogged in. They were diverted to Kinloss, at the northern tip of Scotland.

“As Don brought the aircraft in, a great gust of wind from the starboard side caught our aircraft and just swung it away as our wheels touched down. Don said ‘hold on.’ We were headed for a string of parked aircraft plus buses full of crews.

“Remember, we still had two bombs under our port wing. All I can say is, lucky we had a new aircraft and Don pulled back on the stick and we just skimmed over those aircraft and buses.”

That, however, put them on a collision course with the control tower. Again, their pilot uttered the words, “hold on,” and “he put that aircraft on its wing tip. We made it!”

According to Bomber Command records, two of 282 heavy bombers were downed that day.

Then all hell broke loose.

Three days and one mission later, on Dec. 29, Moyes and his crew, along with three other aircraft, were ordered on a “gardening,” or mine-laying, operation in a Norwegian fjord leading into Oslo.

The airmen were each given two Benzedrine tablets, stimulants known as “wakey-wakey” pills, to keep them alert.

Each plane was loaded with four 2,800-pound mines equipped with parachutes to ease their splashdown. The bombers flew in under a clear sky and near-full moon at less than 2,000 feet (609 metres) to avoid radar detection.

They made their way partway up the fjord, did a U-turn and dropped to 800 feet above the water. Moyes and the mid-upper gunner, Sergeant Alvin Kuhl, fired on a vehicle on a road below. They dropped their mines and headed home.

Two nights later, they did it again, only it was a little more complicated this time.

The mines, for one thing, were rigged to be dropped closer to shore. It was a clear, moonlit night, just like before, but they were in for a surprise.

They made their turn and dropped the mines as planned.

“Then all hell broke loose,” Moyes wrote in a self-published memoir, Coming Home…On a Wing and a Prayer. “Apparently, there were a couple of ships or barges loaded with guns, either 30mm or 40mm. They opened up on us.

“The sky was full of tracer rounds.”

Walkley immediately put the plane into a dive, with Moyes and Kuhl blazing away at 1,150 rounds per gun, per minute.

“We didn’t take our fingers off the triggers,” Moyes wrote. “My guns were white hot when Stu, the bomb aimer, called out: ‘Skipper, pull up, I can’t swim!’ Don pulled up and we were only 75 feet above the water. Only one round…hit us.”

Their long mission ended around sunrise on New Year’s Day 1945. They slept through the noontime turkey dinner and missed out, just happy to be alive.

Over the three years the pathfinders existed, 3,600 were killed in action.

Two months later, the crew decided to transfer to 405 Squadron of No. 8 (Pathfinder Force) Group after they had buzzed a soccer game that turned out to involve the RCAF headquarters team. The players had gotten the aircraft number and Walkley was called on the carpet as soon as they touched down.

“Our goose was cooked, as they say. We got dirt left and right so we all decided we’d better get off that squadron.”

The pathfinders were based at Gransden Lodge, just west of Cambridge.

Flying Lancasters, the pathfinder crews spread clouds of radar-confusing foil and marked the target with illuminating flares two to six minutes ahead of the main force. It was the mission’s most dangerous job for several reasons: the most obvious of which was the fact that because the lead pathfinders—or visual crews—came in first, there were only a handful of planes for the guns below to target and while the bombers came and went, they circled the area for much of the raid.

Other pathfinders, known as blind crews, were distributed through the formations to correct mistakes and keep the increasingly smoky targets visibly marked. In the most unenviable job of all, the master bomber would stay on station until the mission was done. All carried varying bomb loads.

Led by pathfinders, bombers came within five kilometres of targets 73 per cent of the time during the Ruhr campaign in 1943; by war’s end, they were at 95 per cent, said Will Iredale, author of The Pathfinders: The Elite RAF Force that Turned the Tide of WW II.

But it was not without cost. Over the three years the pathfinders existed, 3,600 were killed in action. The average survival was 12 missions, such a high attrition rate that 50 new crews had to be recruited per month for the duration.

New pathfinder crews were broken in slowly, starting out in support roles carrying the same bomb loads as the main force. They graduated to more demanding marking duties as their skills developed.

Moyes said his crew was young but, while they “engaged in a lot of horseplay on the ground, a total transformation took place when we climbed into an aircraft for an operation.” Walkley never had to pull rank, as “everyone had too much sense and self-discipline to require any such nonsense in the air.”

“We were no longer young men fooling around,” he said, “just men with serious business at hand, men who set about doing their various jobs with discipline so as to stay alive.”

As was the practice, Moyes and his crew flew several missions as a supporter crew after a training period with the pathfinders, heading into the target about the same time as the master bomber and deploying the foil known as “window.”

On March 11, 1945, they flew as a supporter on a daylight raid to Essen in the Ruhr Valley. The raiding force was made up of 1,085 aircraft.

“We were at the target in the opening minutes and on our return, aircraft were still going to the target as we reached the English Channel,” he wrote.

More raids into Germany followed—to Hemmingstat, their first as a visual pathfinder; Nuremburg, where the flak was so heavy that “aircraft seemed to be going down left and right…with parts of planes flying around;” and Nordenhausen, where heavy cloud forced them down to 8,500 feet (2,590 metres) and they had to circle the target five times before dropping their bomb load.

The pathfinder crews were the elite of the bomber force. Their training was continuous and more intense than ordinary bomber squadrons. Crews regularly waved their opportunity to go home after 30 missions, routinely massing 40-80, some even exceeding 100.

“A lot had been in trouble at their original squadrons for being a little wild,” said Moyes. “Maybe that’s what got them through all this.”

On April 25, 1945, Moyes and his crew flew pathfinder with a 300-plane daylight raid on the SS barracks at Berchtesgaden in southeastern Germany near the Austrian border.

The target, housing the elite and fanatical Shutzstaffel, was part of Hitler’s mountain resort complex. The bombers were tasked with clearing the way for U.S. General George Patton’s Third Army.

Finally, a call came in over the radio. The master bomber was lost.

It was a near-cloudless morning as the pathfinder crews set out from their base in Cambridgeshire, Moyes’s visual crew heading in with the master bomber followed by seven blind crews distributed through the formation to keep the target marked.

They arrived at the objective about 10 a.m.

“Approaching Berchtesgaden, we could see the resort complex partway up the side of the cone-shaped mountain, on the north side,” he wrote. “On top of the mountain is the ‘Eagle’s Nest’ which was Hitler’s tea room.”

There was no sign of the master bomber or the main force when they arrived, so they circled the target three times. Lucky for them, there was no flak. Finally, a call came in over the radio. The master bomber was lost.

“We had never heard of such a thing,” Moyes said.

The leader told them to go ahead and drop their markers. The main force arrived from the south soon after. Moyes and his crew hung around to watch the fireworks as 300 aircraft descended on the target, including eight planes from 617 (Dambusters) Squadron loaded with 12,000-pound bombs. The smoke was so thick, Moyes’s crew decided to make for home.

“Back at the base, the first thing they told us was that Hitler had left Berchtesgaden around midnight for Berlin.”

Moyes, who re-enlisted after the war and served 28 more years in the air force, took his family and toured the site while stationed in Germany in 1963. “I met the head waiter of the hotel who was there during the raid. We had a nice talk.”

As the war drew to a close in early May 1945, Moyes and his crew flew low-level relief missions into the Netherlands, dropping food to the Dutch in Rotterdam on Operation Manna.

“At a height of 350 feet, we could see the people waving; they were starving.”

On VE-Day—May 8, 1945—the crew, minus Moyes and Kuhl, flew into Lubec, Germany, to pick up Allied prisoners of war and take them back to England.

That night they partied.

Moyes and some of his crew volunteered for service against Japan.

No. 405 was one of six RCAF squadrons picked to head to the Pacific theatre after the war in Europe ended. They flew back to Canada in June 1945 and joined several other Lancaster squadrons at Greenwood, N.S., to prepare.

Moyes and some of his crew volunteered for service against Japan, but before anything came of it, the Americans dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The war was over.

An armourer in his second life with the RCAF, Moyes married Margaret Winters of Belleville, Ont., in 1948. They had a son and daughter and were together for 72 years before she died in 2020. He left the air force in 1974, then joined the RCMP forensic laboratory, where he worked as a civilian firearms technician for 15 years.

“A great bunch of guys,” the bomber crew would keep in touch and hold periodic reunions over the years. Now Moyes is the last surviving member, and he still keeps in touch with their children and grandchildren.

“We were very close; we got along so well together,” he told Legion Magazine, adding he would do it all over again, if he could. “There were scary moments sometimes but I was young. I joined up looking for excitement. And I got it.”

Advertisement