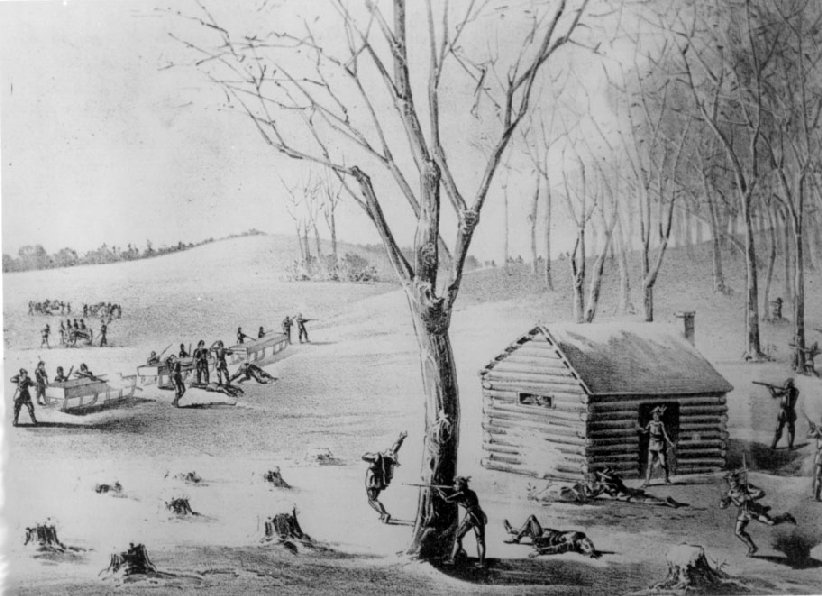

Members of the North West Mounted Police battle with Louis Riel’s Métis militia at Duck Lake, Sask. [The Canadian Pictorial & Illustrated War News/Wikimedia]

The buffalo were disappearing, the government had stinted on promised treaty payments and on food rations, leaving many Prairie First Nations on the brink of starvation. The Métis worried about recognition of their right to own land in the face of government land promises to the railways, an influx of settlers and government surveyors moving in to reshape long, narrow Métis river lots to conform to the township system’s square shapes.

Decisions that affected their fates were being made thousands of kilometres away, without First Nation or Métis input and by people who turned deaf ears to their concerns and pleas for help.

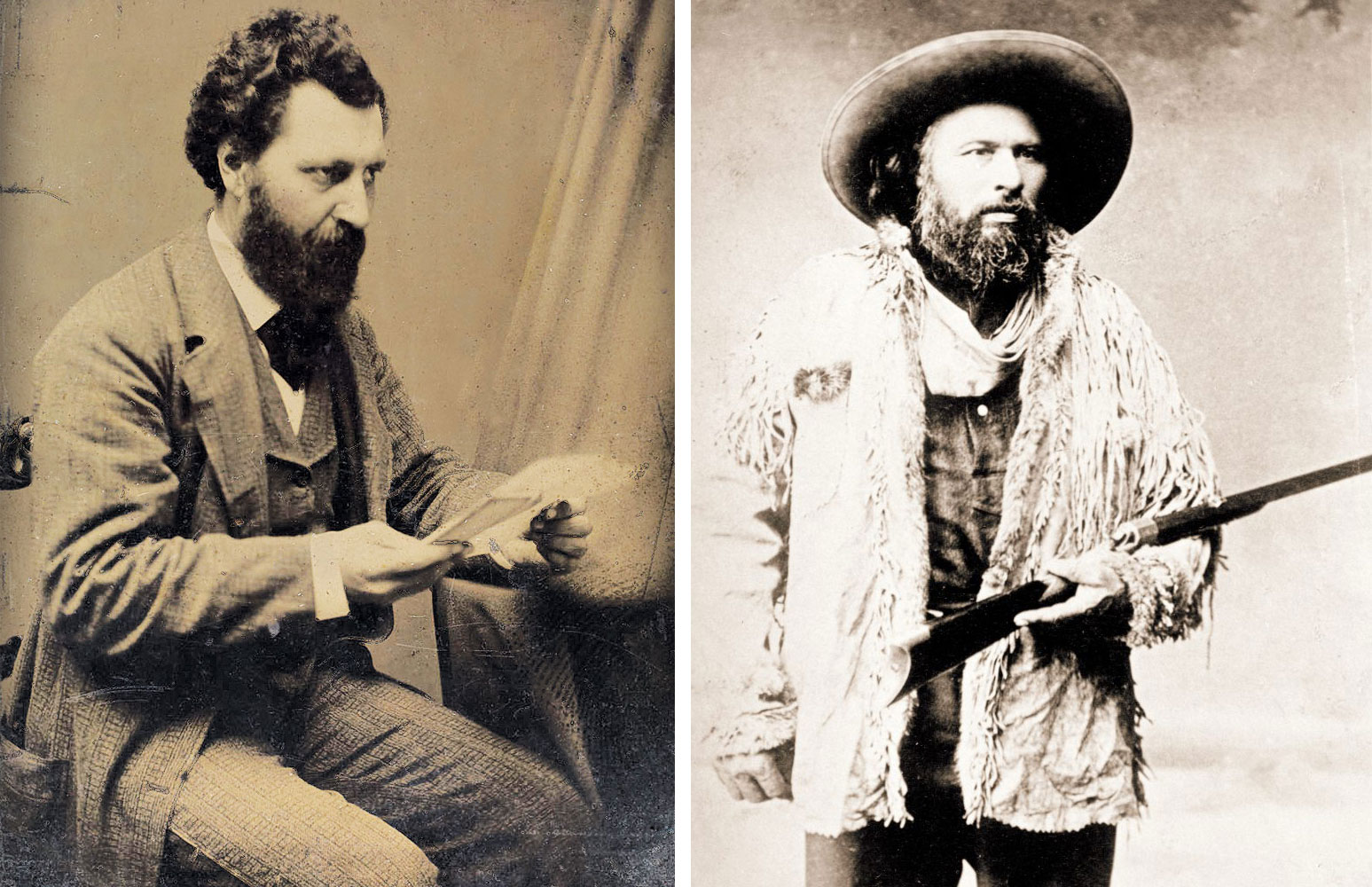

Louis Riel urged them to combine their voices, winning over the Métis near Batoche and the Plains Cree followers of Big Bear and Poundmaker. However, not all Métis settlements or First Nations joined him.

But there was enough support to pass a bill of rights on March 8, asserting Métis rights to possession of land, and 10 days later to form a provisional government at Batoche, with Riel as president and Gabriel Dumont as military commander.

Louis Riel (left) and Gabriel Dumont. [LAC/MIKAN 3195256; LAC/PA-178147]

On March 26, a force of about 100 North West Mounted Police and armed citizens commanded by Superintendent Leif Crozier came up the trail to Duck Lake. They were met by Dumont and his men. Words were exchanged; a scuffle broke out between a Mountie interpreter and a Cree emissary.

Shots were fired. In the following fight, five Métis, one First Nations warrior, nine civilians and three Mounties died before the Mounties retreated.

The resistance spread, leading to more violent clashes. But using the partially completed railway, the government sent 5,000 troops to put down the rebellion. The last shot was fired on June 3.

Riel was convicted of treason and hanged, along with several followers. Poundmaker and Big Bear were sent to prison for three years. An amnesty was declared for those involved in the resistance in 1886. Dumont returned to Canada seven years later and died in 1903.

Echoes still reverberate.

Advertisement