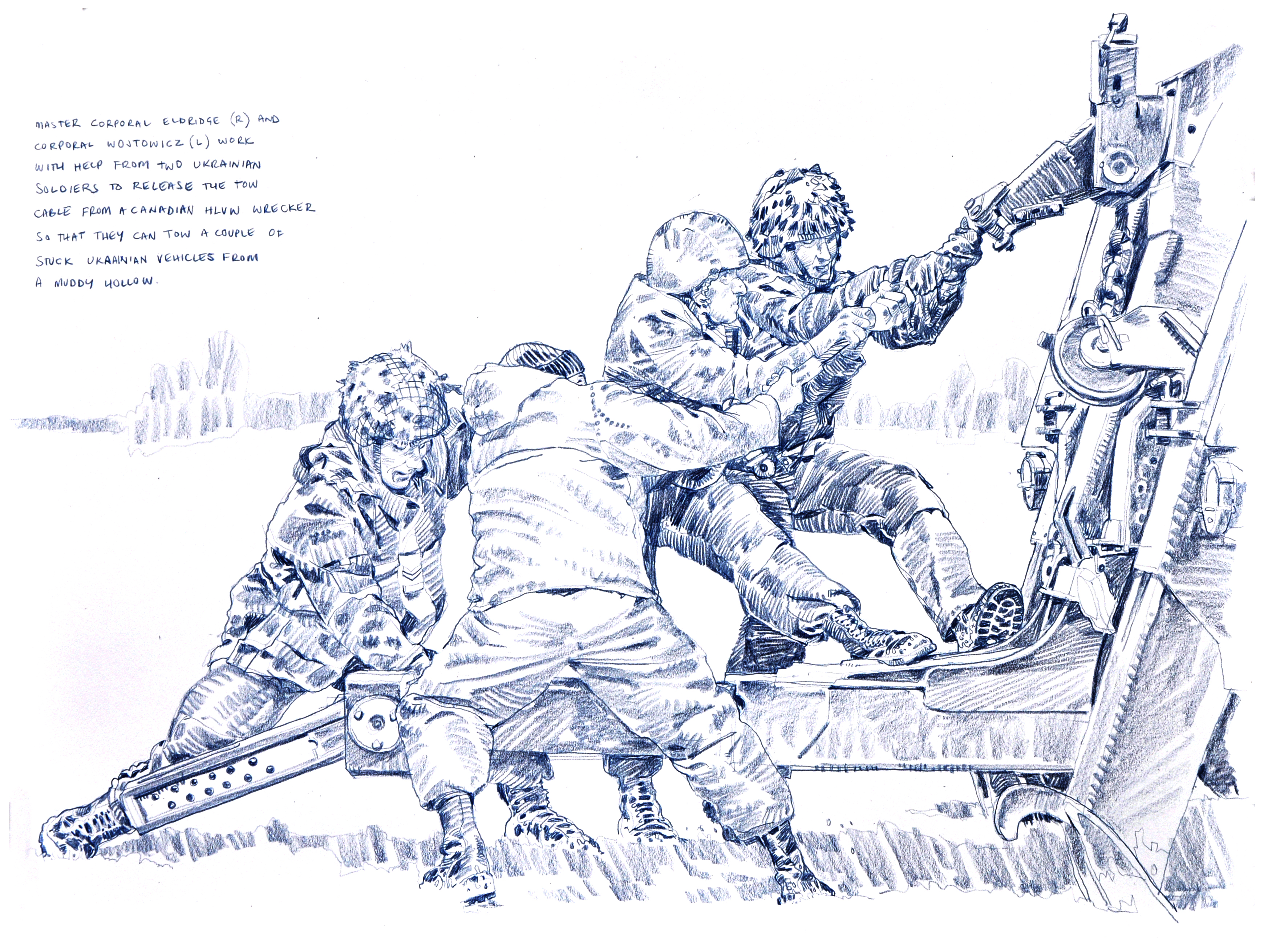

Two Canadian and two Ukrainian soldiers release the tow cable from a Canadian HLVW wrecker. [Wrecker, 2015 By Richard Johnson]

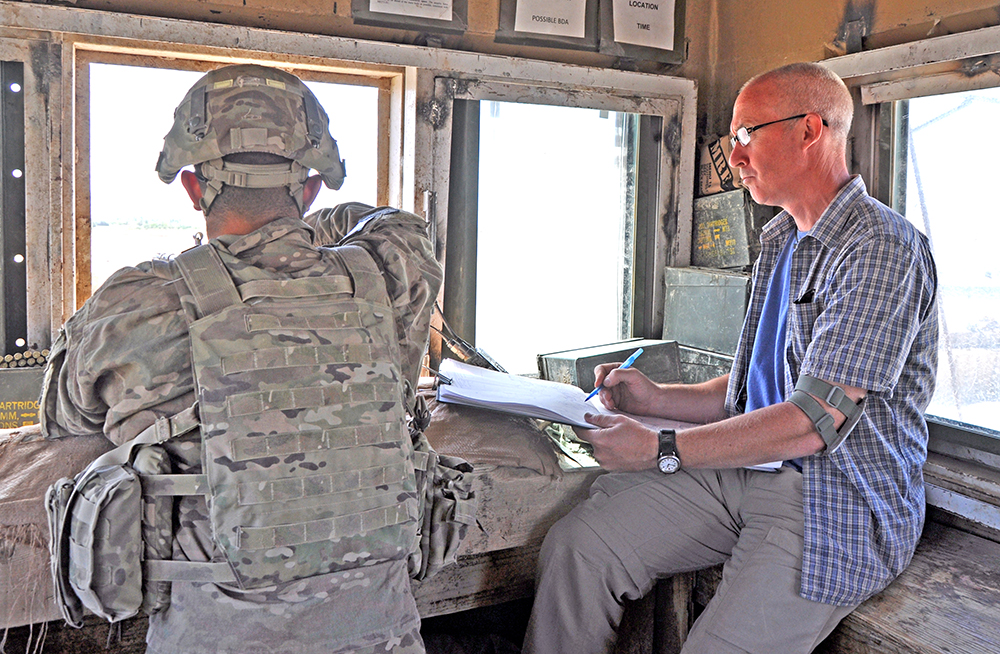

Born in Scotland and now living in Maryland, the man technically known as a news illustrator has taken the art of war back to its roots, drawing for the Detroit Free Press in Iraq, The National Post in Afghanistan, the United Nations in Africa and for the Washington Post, where he was graphics editor.

His work has toured the United States, it is in the permanent collections of Washington’s Smithsonian National Museum of American History and the National Museum of the Marine Corps in Virginia and now it is part of a military-themed art exhibition at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa.

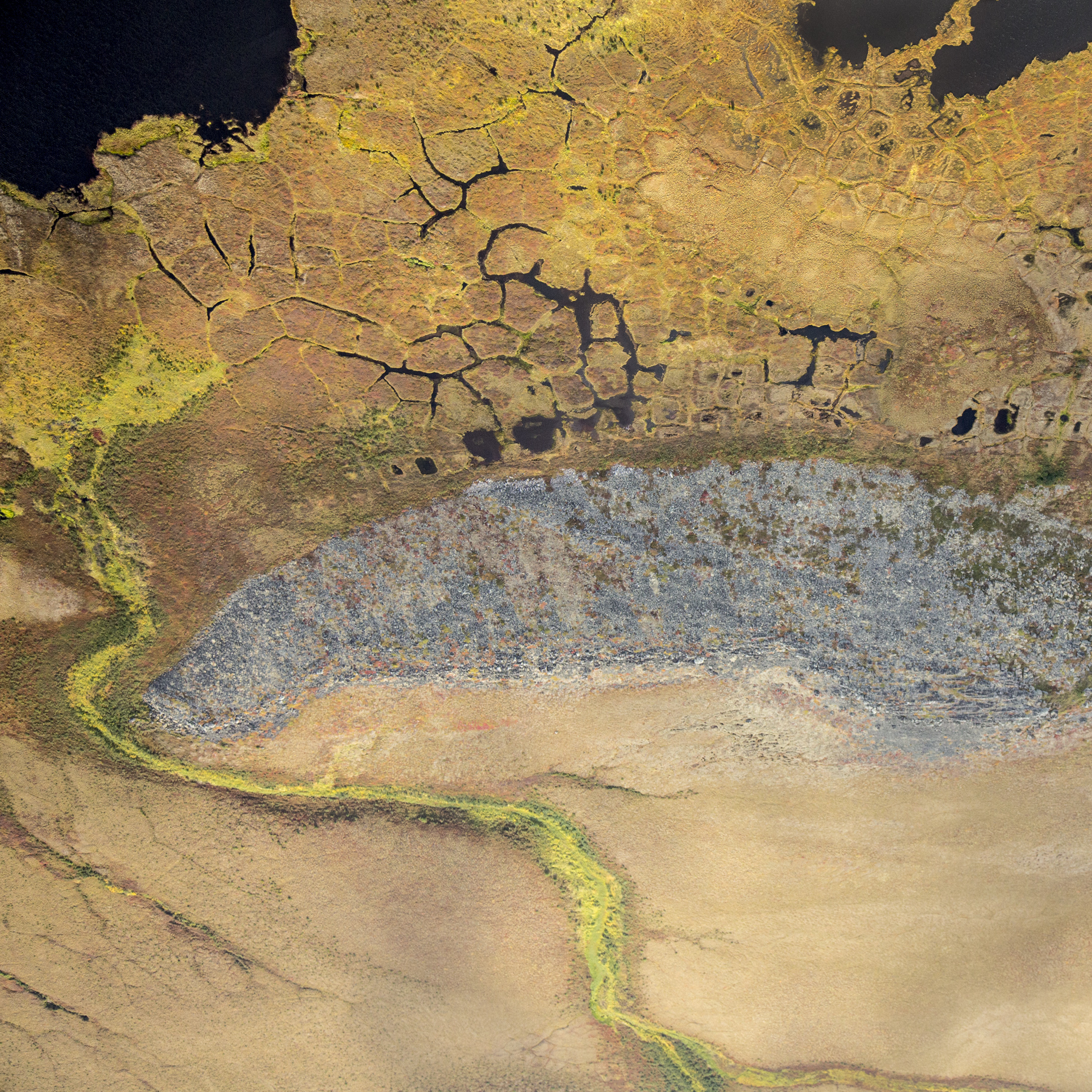

Ship’s Wake, # (1-16), 2016-2017 by Ivan Murphy. Oil on wood panel. [Ivan Murphy]

Their work is widely varied, from Mark Thompson’s enamel-on-glass images of Kuwaiti blast shelters and underground bunkers to Nancy Cole’s Night and Day, conceptual, minimalist hand-quilted textiles representing CF-18s on deployment.

Cryosol series #37 by Guy Lavigueur. Pigment print on archival paper. [Guy Lavigueur/Courtesy of Galerie La Castiglione, Montréal]

It is Johnson’s work, primarily featuring individual soldiers, that most reflects early documentary war art, hearkening to a time when drawings served as visual reportage and preceded the photograph in newspapers and magazines.

In their heyday, they were the images of record, distilled from the grand, colourful, idealized re-creations of Napoleon’s glorious victories, Nelson and Wolfe’s heroic deaths and Washington’s stalwart crossing of the Delaware River.

Johnson’s signature work reflects the daily life of the soldier on duty. Under the artists’ program, he joined Canadian troops on deployment in Ukraine in 2015.

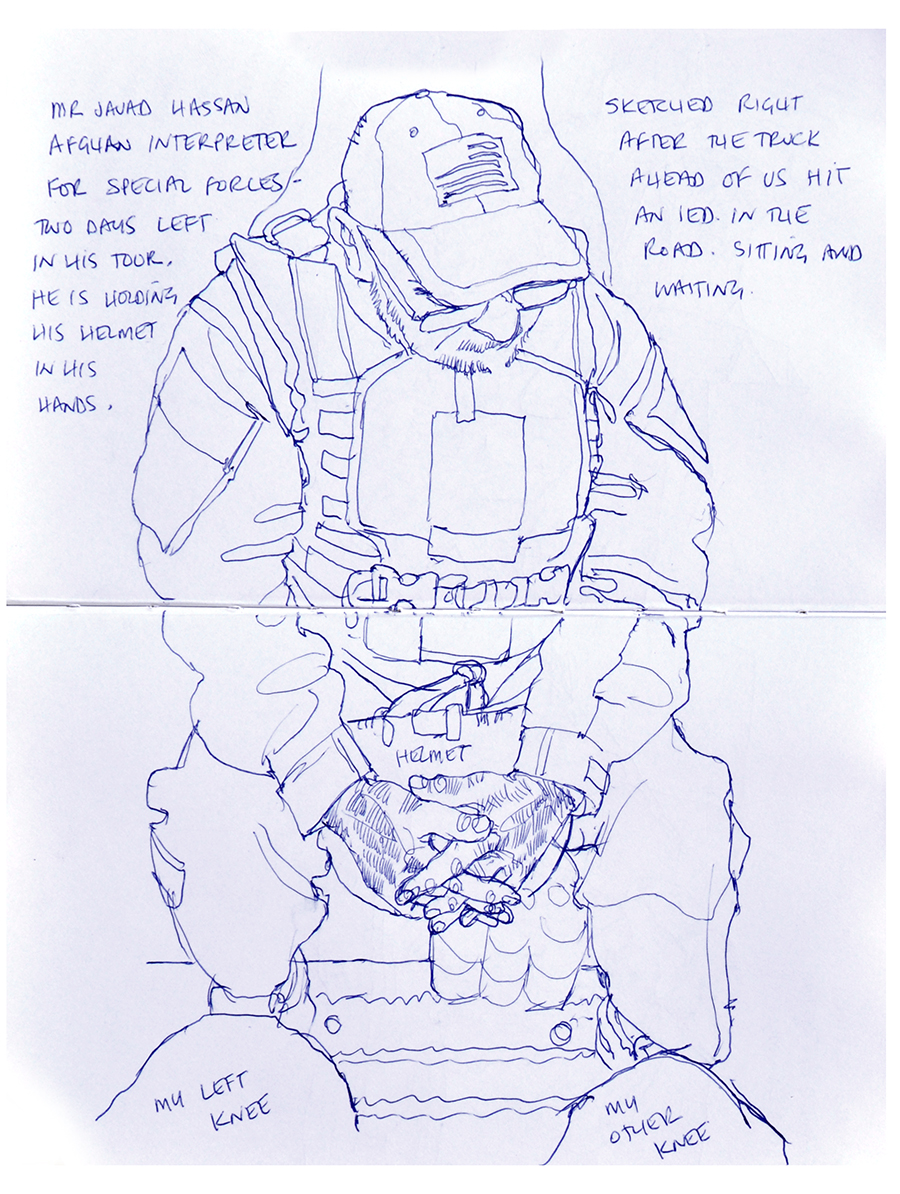

“If I have one guiding principle, it is that I draw what I see,” he says, echoing the advice of his mentor, Second World War artist Howard Brodie, who drew the siege around Bastogne, Belgium, and the landings at Guadalcanal in the southwest Pacific Ocean. “I don’t alter, and I don’t stage.”

Afghan interpreter Javad Hassan sketched immediately after the truck ahead was hit by an improvised explosive device. [Richard Johnson]

In one exhibition image, reminiscent of photographer Joe Rosenthal’s iconic “Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima,” Canadian and other troops haul the rigging from a tow truck as they prepare to free vehicles stuck in mud.

In another, Corporal Adam Tofflemire of 1st Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment, makes his way through long grass wielding a non-issue Kalashnikov rifle.

The drawings are highly detailed and painstakingly accurate. Johnson says there is a value to hand-drawn images of war that photographs cannot capture.

While Smithsonian curators reviewed his submissions, the artist was given the freedom to roam the institution’s archive of military art. He viewed sketches of First World War battles that looked as current as the day they were drawn—a distinct departure from photography, whose look and feel immediately dates it.

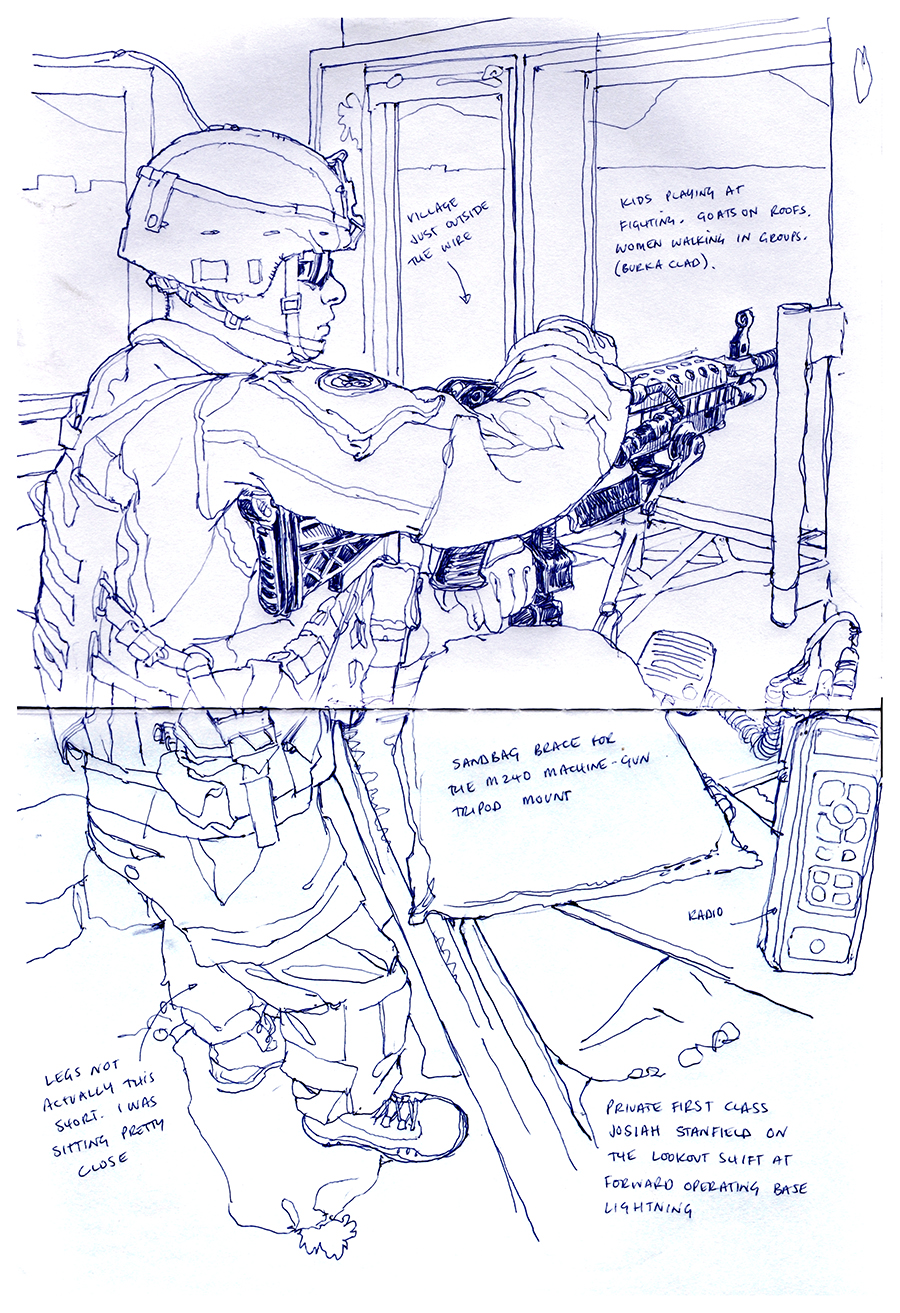

Richard Johnson (TOP) drawing 3rd Cavalry Reg. Private 1st Class Josia Stanfield in the lookout tower at FOB Lightning in 2014. (ABOVE) The actual sketch. [Richard Johnson]

The human element, absent of technology, also contributes to the war art experience, especially in an age when we are bombarded with electronic images of every genre via television and the Internet.

“There is something about viewing a subject through a human being as the lens that has a very human contact to it. There is something very visceral about it when it is viewed that way.”

The modern-day roots of Canadian war art lie in the museum’s 14,000-piece Beaverbrook Collection, comprising works from both world wars and subsequent conflicts.

Between 1916 and 1919, the Canadian War Memorials Fund established by newspaper baron Max Aitken, better known as Lord Beaverbrook, along with Lord Rothermere financed nearly 1,000 war-related works by more than 100 artists from Canada, Britain, Australia, Yugoslavia and Belgium.

Group of Seven artists A.Y. Jackson, Frederick Varley, Arthur Lismer and Frank Johnston were among those who created pieces under the program, which focussed exclusively on Canada’s role in the Great War. Postwar exhibitions in London and New York helped launch their careers.

Lieutenant Alfred Bastien’s painting, “Canadian Gunners in the Mud,” depicts a group of soldiers struggling to free their sunken gun from the sea of mud at the Battle of Passchendaele. The original is part of the Canadian War Museum’s 14,000 piece collection of war art. [Lieutenant Alfred Theodore Joseph Bastien/CWM/19710261-0175]

No program was initiated during the Korean War, though a handful of soldiers such as Ted Zuber recorded their front-line experiences upon returning home. From 1968 until it fell to budget cuts in 1995, the National Gallery of Canada administered the Canadian Armed Forces Civilian Artists Program, which dispatched artists to record Canadian operations in Europe, Vietnam and the Middle East.

The current version involves selected groups of artists from across Canada working in two-year rotations and deploying once with Canadian forces for about 10 days. They retain copyright, as well as their independence, and are not paid.

The exhibition is on at the Canadian War Museum until April 2.

Advertisement