Anna Stamers, Margaret Macdonald and Jessie Brown Jaggard (opposite, top to bottom) played critical roles during the First World War as nurses.[Imperial War Museums/Wikimedia; Canadian Nurses Association/LAC/e003525007; Imperial War Museums/Wikimedia]

Canadian Nursing Sister Anna Stamers of Saint John, N.B., bound for England aboard Metagama, pondered her fate across the ocean.

Having graduated from her local nursing school in 1913 before accumulating two years’ relevant work experience, the Maritimer appeared prepared for the challenge ahead that June 1915—at least on the surface.

The reality, as is so often the case with conflict—regardless of specific roles and duties—

seldom matched expectations.

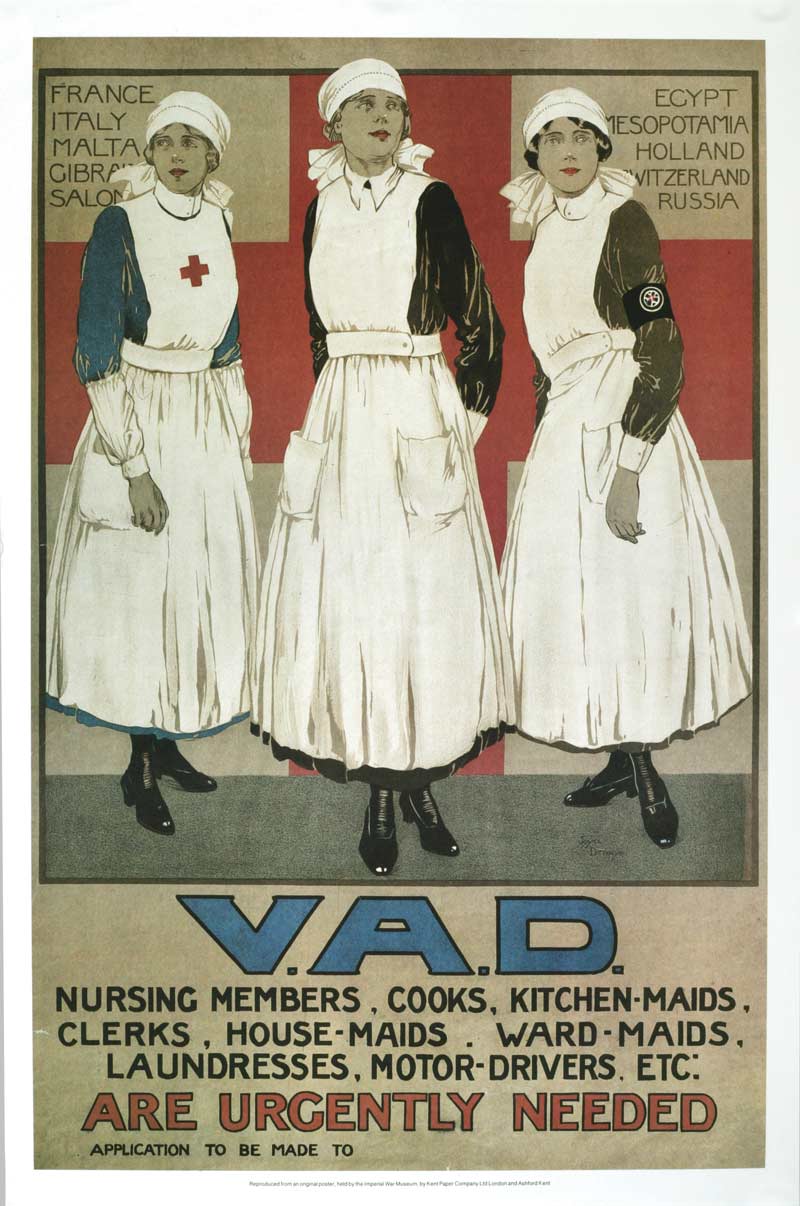

An in-demand role as this recruiting poster for the Voluntary Aid Detachments.[CWM/19920143-009]

Indeed, for Stamers and the 2,844 other nurses who served in the Canadian Army Medical Corps (CAMC) during the First World War, destiny brought many of the same horrors witnessed and experienced by soldiers on the front lines.

And like those soldiers, not every nurse would sail home.

Such realities, however, were not without precedent.

The ward of a Canadian Casualty Clearing Station in Valenciennes, France, in November 1918.[DND/LAC/3395899]

While organized military nursing boasted strong roots in the 1853-1856 Crimean War, women had acted as battlefield caregivers long before the groundbreaking work of Florence Nightingale and Mary Seacole.

In Canada alone, Jeanne Mance and the nursing sisters of St. Joseph de La Flèche had tended to wounded troops in 17th-century New France. Canadian nurses had also served in the 1885 North-West Resistance, as well as during the 1899-1902 Boer War.

When war was declared in 1914, an influx of more than 1,000 applications showed that Canadian nurses were again willing to answer the call.

Matron-in-Chief Margaret Macdonald (second from right) and nursing sister colleagues in wartime London.[DND/LAC/3382663]

Like their male counterparts, motivations to serve varied, although adventure, duty, status, career aspirations and financial security were the most common factors. Unlike their arms-bearing comrades—a high proportion of whom were immigrants—some 83 per cent of WW I Canadian nurses were born in the country.

The earliest months of the war had nevertheless seen applicants whittled down to only the most eligible, a task carried out by Matron-in-Chief Margaret Macdonald. Noted as the first woman in the British Empire to achieve the rank of major, Macdonald had initially selected just 100 nurses to join the CAMC.

Many more, not least the 27-year-old Stamers, followed when the desperate need for additional support became evident.

Among the requirements, those chosen were expected to be well-trained, experienced and display traits deemed appropriate for the dynamic, high-pressure environments they would soon encounter.

Almost always unmarried, the nurses’ average enlistment age was 29.9, making them slightly older than most soldiers in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF)—sometimes dubbed their “boys” when admitted as patients.

Canadian nursing sisters, as they were called despite the lack of religious affiliations, were commissioned as lieutenants with equal pay to men of the same rank. This, along with the women’s sharp blue uniforms, white aprons, CAMC buttons, and two stars on the shoulder straps, became the envy of their British peers. Their distinctive appearance, meanwhile, earned them the affectionate nickname, Bluebirds.

A capacity for tenderness would be necessary once the women established themselves at hospitals and casualty clearing stations, the latter a short distance from the front and often well within range of enemy artillery fire.

Yet perhaps above all else, the Bluebirds required resolve to deal with the lethal efficiency of industrialized warfare—as they would soon discover.

Katharine (Kate) Wilson of Chatsworth, Ont., came to understand flesh torn from the body, muscles ripped to shreds, limbs turned gangrenous, and bones splintered into countless pieces. As part of No. 3 Canadian Stationary Hospital situated in the Dardanelles theatre in 1915, there was an equally deadly killer to contend with.

“Here,” wrote the Canadian nursing sister, “practically every man admitted was critically ill with fevers that left them eventually worn to skeletons.”

While disease itself was hardly a surprise, the global nature of the Great War brought with it varying health-care challenges. On the Western Front after the Second Battle of Ypres, it was gas; on the Greek island of Lemnos in support of the ill-fated Gallipoli Campaign against the Ottomans, dysentery had run rampant.

On Sept. 25, 1915, the pestilence claimed 42-year-old Matron Jessie Brown Jaggard of Wolfville, N.S., a figure held in high regard by the nurses, and who left behind a grieving cousin in Prime Minister Robert Borden.

Gerald Moira depicts wartime action at the No. 2 Canadian Stationary Hospital in Doullens, France.[Gerald Moira/CWM/19710261-0427]

“Lying with the picture of her seventeen year old son smiling down at her,” Wilson recorded of the beloved matron’s death, “one night she closed her eyes for the last time and slept. In her service blue uniform…covered with a British flag…and carried by boys who knew and loved her, she was laid to rest. Forever she will remain in the hearts of those who were privileged to serve under her.”

With additional Canadian deaths anticipated, a makeshift cemetery was created. Beside these premature graves stood a sign reading: “For Sisters Only.”

Despite the daily reminder of a perceived fate while plagued by dust and flies, Wilson and her fellow nurses continued under increasingly difficult conditions.

Whether assisting medical or surgical procedures, performing therapeutic nursing techniques, maintaining wards, providing bedside care or carrying out administrative tasks, Bluebirds were typically the backbone of CAMC units.

They also found themselves on the front line of advances in medicine, be it dealing with infection or evolving perceptions around shell shock.

Moreover, when supplies became scarce and, particularly in the case of Lemnos, when temperatures could fluctuate dramatically, simple acts such as a few kind words or an encouraging smile were critical to patients’ morale.

Frequently, of course, compassion could do little to mend bodies shattered beyond healing. In these instances, nursing sisters might showcase their tenderness by joining chaplains in the final hours with dying soldiers.

Holding hands as their boys slipped away, the women could be mistaken for angels sent from above to guide lost souls to the next world.

But then it was on to the next bed, the next soul, as nurses—and all caregivers—found ways to cope with the intense emotional strain.

On Nov. 26, 1915, a freak storm struck Gallipoli. More than 200 troops drowned or froze to death in flash floods and a blizzard. Another 5,000 were evacuated from the peninsula for hypothermia and trench foot.

Writing after the latest inpouring of patients, Wilson noted that “many of the cases became gangrenous, and many feet had to be amputated.”

Only in January 1916, when the Allies withdrew from Gallipoli, did Wilson escape the flies, dust and death of Lemnos.

Death, though, would follow her.

As the CEF expanded between 1914-1916, so did the CAMC on the Western Front—including at Anna Stamers’ No. 1 Canadian General Hospital.

Many facilities had more than 1,000 beds and a staff at full strength of 30 medical officers, 70 nurses and 205 other ranks. During the war, the CAMC eventually grew to comprise 37 overseas medical units with a combined bed capacity of 14,000, counting specialist hospitals and wards.

In the meantime, Stamers settled into the steady flow of tending to sick and wounded during the supposedly quieter periods between great battles. Even in the absence of large-scale campaigns, there was no shortage of work in the wards, where Stamers and her comrades performed their daily duties while forming strong bonds.

In June 1916, she developed a severe ear infection and spent several weeks hospitalized. She returned from her convalescence at the end of the month.

July 1 was the first day of the Battle of the Somme, and Canadian caregivers across the front required all the assistance they could get.

Orders soon arrived at Étaples, where the hospital was situated, for six nurses to proceed to casualty clearing stations closer to the fighting. Fully understanding the dangers, the women departed, leaving the remaining staff stretched thin.

A nursing sister assists in the operating room at No. 10 Casualty Clearing Station in July 1916.[CWM/19920085-704]

Stamers almost certainly shared in her fellow nurses’ sense of foreboding as the wounded streamed in like a ceaseless torrent. By the end of July, No. 1 Canadian General Hospital had handled 4,363 admissions, of which 3,808 resulted from wounds and 555 from disease. Of those, however, just 51 soldiers died, standing testament to professionals such as Stamers and her colleagues.

Whenever possible, from the Somme to Vimy Ridge to Hill 70 to Passchendaele, it was the CAMC’s task to get bedridden soldiers back on their feet so they might fight once more. The glaring irony wasn’t lost on personnel that their life-saving interventions could facilitate the taking of further life.

Nevertheless, some patients would never return to the trenches, instead spending the rest of their shortened lives forever changed.

“Perhaps the head cases were the most harrowing,” wrote Kate Wilson of dealing with what she saw as the truly helpless cases. “A boy would come in with all his senses, and suddenly I would hear a scream, and would find that he had gone absolutely insane, often with all his bandages torn off, and his wound haemorrhaging, with particles of his brain oozing out of the open wound.”

Nor were the Bluebirds themselves immune from similar wounds.

Mustard gas, still lingering on its victims, could cause doctors and nurses to go temporarily blind. Infection and disease, as had happened to the late Matron Jaggard in Lemnos, spread to medical staff. Then there were the women close enough to the front to be in the firing line of enemy shells.

In March 1918, after about three years of static lines, the Germans launched a penetration into Allied territory. Imperilled facilities, together with their wounded—some of whom were unlikely to survive the move—attempted to withdraw on clogged roads.

By May, enemy air raids had begun disrupting the Allies’ transport and communication hubs, with bombs dropping perilously close to hospitals. Marked with large red crosses, CAMC units should have been safe. They weren’t.

Nursing sisters attend to a soldier wounded during the capture of Hill 70 in France in August 1917.[DND/LAC/PA-000364]

Stamers was not in Étaples when No. 1 Canadian General Hospital was attacked on May 19, 1918. She did not see the flames rise, hear the screams or smell the charred bodies as 66 Canadians, including three nurses, died.

Among those killed was nurse Katherine MacDonald of Brantford, Ont. Writing the day before the raid, she had assured her mother of being “far from harm.”

Additional air raids—war crimes—were carried out during the subsequent weeks. On May 30, No. 3 Canadian Stationary Hospital, by then having been relocated to Doullens, France, was targeted. Three more nursing sisters died alongside two surgeons, 16 orderlies and four patients.

Kate Wilson likewise escaped the casualty list. In 1917, she had returned home to Canada, where she married Captain (later Major) Robert Simmie and eventually had six children in Wiarton, Ont. Her experiences as a nurse were later published in her memoir, Lights Out!. She died in 1984, aged 95.

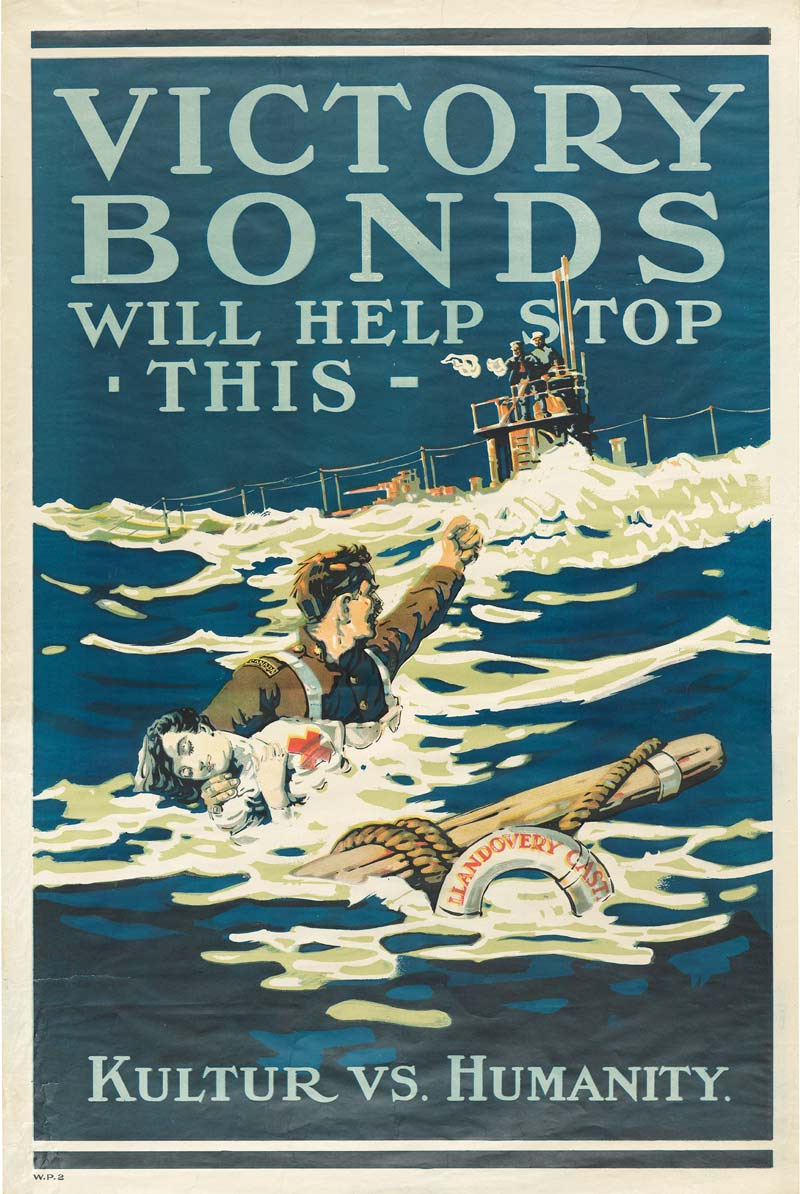

Nearly a year later, 14 Canadian nurses drowned after a U-boat attack on hospital ship Llandovery Castle—an incident used to inspire continued support for the war.[CWM/19850475-014]

Stamers had been absent from the onslaught for a very different reason: she had been transferred to the Canadian hospital ship, Llandovery Castle.

On June 27, 1918, the now 30-year-old nurse was bound for England on a journey not dramatically dissimilar to the one she had taken three years earlier. That changed, however, when a German torpedo struck the red cross-emblazoned vessel.

Llandovery Castle sank beneath the waves within 10 minutes with the loss of 234 souls, many of whom were murdered by U-86 when the submarine began ramming lifeboats and gunning down survivors to cover up the crime.

The 14 nurses aboard all perished when the suction from the descending ship drew them down with it. This, tragically, was Stamers’ fate, along with any written accounts she had kept at the time.

But her story, and the story of some 60 nurses killed or who died of wounds during the Great War, remained alive with the women who did sail home.

Some had or would write of their exploits for future generations. Others, like countless male comrades, chose to bury their experiences. Yet more stayed on in the immediate aftermath of the conflict to contend with the influenza pandemic sweeping across the planet. Many, however, would struggle to stay in the profession due to few nursing jobs back in Canada.

Regardless of how individual Bluebirds interacted with their veteran status, their collective service and sacrifice was immortalized in August 1926 when the Nurses’ Memorial was unveiled in Parliament.

Today, the marble sculpture, depicting in part nursing sisters tending to a wounded soldier, reminds onlookers that war can seep into every facet of society, from those at the front to the ones left to pick up the pieces.

Advertisement