The crew of Iroquois gathers in remembrance of the three personnel killed in action in Korea.

After being attacked by Korean shore batteries, HMCS Iroquois wound up with a shiny new ship’s bell unlike any other in the navy

The only Canadian ship to suffer deaths due to enemy action in the Korean War, HMCS Iroquois (DDE 217) joined the fight there on June 12, 1952, and was assigned patrol duty on the west coast.

“We were always in close proximity to the 38th parallel,” recalled Ron Kirk in a Memory Project interview. The crew had to be ready for action at all times.

“We would go on patrols three to six weeks at a time. At night we would anchor out and we had armed guards walking around the upper deck and a 40-millimetre Bofors gun armed. We had to sit by that gun for our four-hour watch and be ready in case there were any problems,” said Kenneth Snider.

In late September, the ship was assigned to fire on rail lines that threaded through tunnels ranging along the east coast.

“This line was a main supply line for the North Koreans,” said crewman Peter Fane. Trains, rail lines, tunnels and repair parties were targets. “As soon as the workmen saw our gun flashes they ran for cover into the tunnel for safety.” Slowing down repairs extended the time the railway was unable to move war supplies.

On Oct. 2, Iroquois was called in to support a U.S. destroyer that had come within range of shore batteries along a stretch of railway where a dozen ships had already suffered damage and casualties. After firing into the entrance of a tunnel, Iroquois turned to leave, presenting its broadside which was immediately targeted by shore batteries.

Two shells straddled the ship. The third hit the gun just below the bridge, killing or mortally wounding three crew and injuring 10 others.

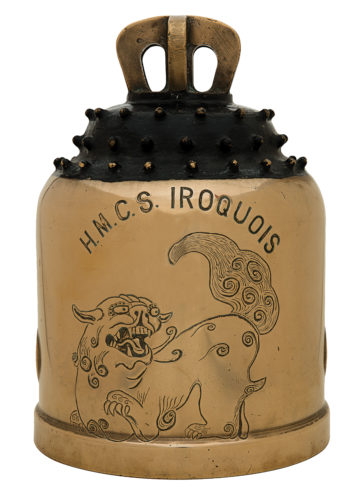

Iroquois’ unique bell was cast in Japan from brass shell casings to replace the one lost to enemy fire. [CWM/19700165-005]

Lieutenant-Commander John Quinn was killed instantly, along with Seaman Elburne Baikie, who had been loading a four-inch shell, which exploded and took the legs of Seaman W.M. (Wally) Burden, who died a few hours later.

The ship remained on station for 11 days after being hit, then sailed for a dry dock at the UN naval base in Sasebo, Japan. Among the repairs was a replacement for the ship’s bell, which was lost in the battle.

The silhouette of an Indigenous brave is featured on the ship’s badge of HMCS Iroquois, a Tribal-class destroyer. [CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum]

There was a shortage of metal in postwar Japan, so Iroquois supplied brass shell casings used in battle. The new bell was unlike any other in the navy. Having been cast in the year of the dragon, an image of the mythical monster was engraved on the outside of the bell, along with the name of the ship. The bell was shaped like a Japanese temple bell and not with the flaring rim of traditional ships’ bells. It also had an external striking apparatus instead of an internal clapper.

After repairs, the ship went back to work and it was not fired upon again in its final two tours to Korea, although the enemy had “ample reason and opportunity to do so,” said its captain, Commander W.M. Landymore, quoted in Canadian Naval Operations in Korean Waters.

Advertisement