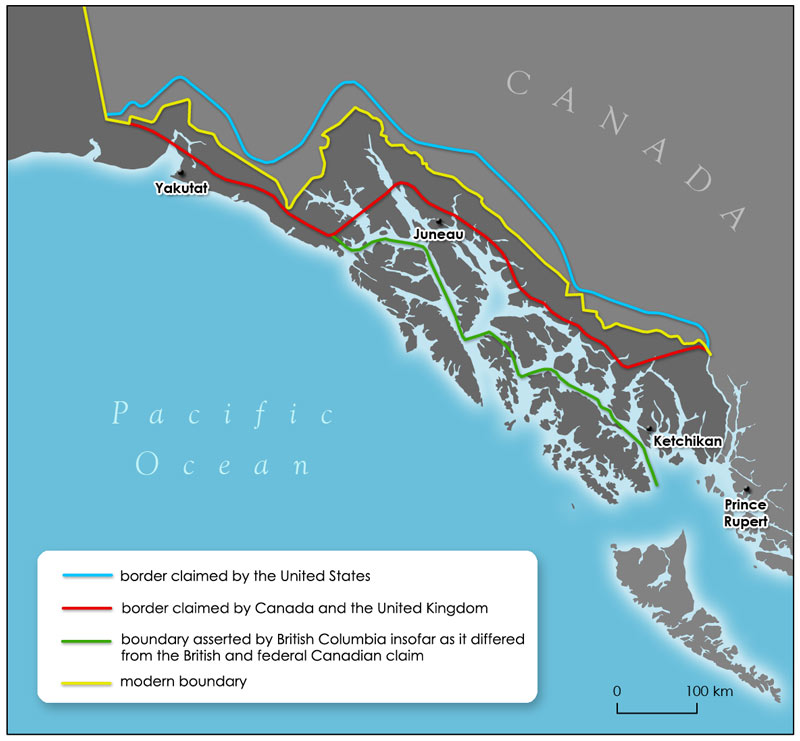

The international border between Yukon and Alaska in the early 1900s. [Wikimedia]

One of those disputes ended with Yukon being cut off from sea access by the Alaska Panhandle. It’s a border dispute that Canada lost more than a century ago that has ramifications reverberating to this day.

It began with an accord between Russia and Britain that was established before the northwest part of North America had been fully explored and mapped.

Both Russia and Britain had colonial interests in the territories today known as Alaska and British Columbia. The two countries signed a treaty in 1825 delineating the border between their territories.

The agreement said the border would travel north along Portland Canal to the 56th parallel north, and then follow the summits of the mountain range parallel to the coast to the 141st meridian west, not exceeding 10 marine leagues from the coast (about 16 kilometres).

Problem was, some assumptions made about the geography of the area later proved to be untrue, a factor of not much importance when the area was sparsely populated and of little commercial interest.

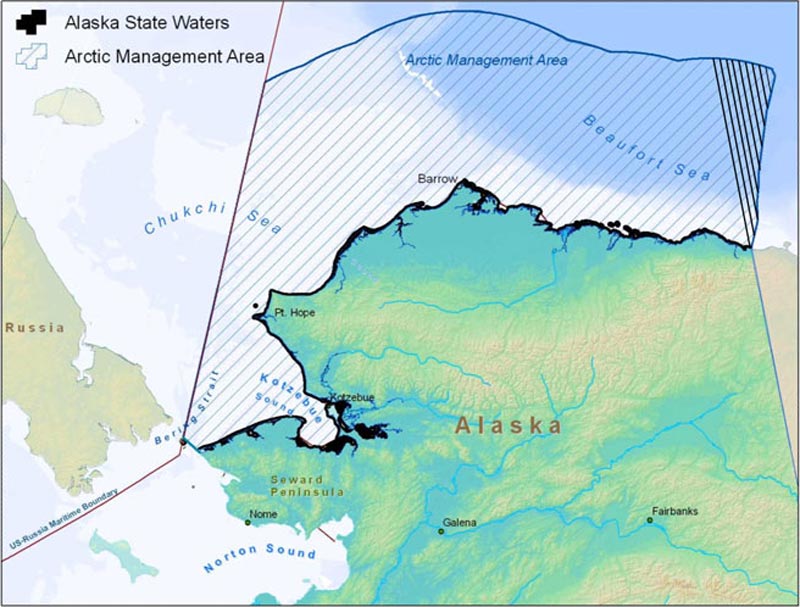

Alaska’s boundary disputes before the arbitration between the U.S. and the U.K. in 1903. [Wikimedia]

The two sides wrangled for several years until the Russian government, which wanted to improve relations with Britain, ordered the Russian trading company to settle the dispute. An agreement was hammered out in 1839 and it was subsequently modified and renewed many times.

Then on Oct. 18, 1867, the Russian Empire sold its territory in Alaska to the United States. The Hudson’s Bay Company continued to operate under the terms of the agreement with the Russians, despite American misgivings.

When British Columbia joined Confederation in 1871, Canada requested a boundary survey, but the Americans rejected the proposal as too costly. Alaska was a long way away and had a small population. The United States offered to permanently lease a port to Canada, but the offer was refused.

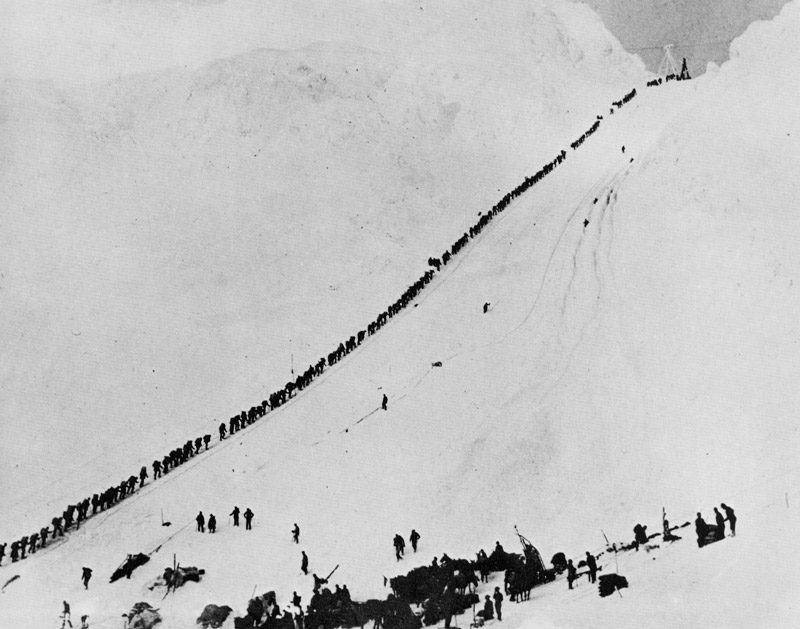

Things changed when gold was discovered in Yukon, attracting about 100,000 men hoping to strike it rich in the Klondike Gold Rush in 1897. Suddenly the U.S. was interested in setting an exact border.

Miners and prospectors ascend the Chilkoot Trail during the Klondike Gold Rush in 1897. [Eric A. Hegg/Wikimedia]

The U.S. was forced to accept a provisional boundary and negotiations began again. It was complicated by references to the 1825 agreement, which had been written in French, inviting disagreement over interpretations, and was based on the incorrect assumption that the mountains were continuous and parallel to the coast.

The disagreement went to arbitration in 1903. A decision was rendered on Oct. 20 and although Britain signed the award, Canada did not. Being in the minority, its objections were disregarded. It felt betrayed by Britain, which was at the time currying favour with the United States. The Yukon was left with no southern access to the sea.

The heart of the disagreement is over a living resource: Pacific salmon.

The land boundary issue was settled, but a dispute remains over the sea boundary.

Canada holds that the dividing line extends from the land straight out to sea. The U.S. argues the arbitration agreement covers only the land border and by maritime law the sea boundary extends 20 kilometres into Dixon Entrance, southwest of the point where the B.C.–Alaska border kisses the Pacific Ocean northeast of Haida Gwaii.

The heart of the disagreement is over a living resource: Pacific salmon, five species of which move through Dixon Entrance, maritime riches that sustain populations on both sides of the border.The Pacific Salmon Treaty and other agreements have attempted to ensure fair sharing of the resource, but tensions flare from time to time, most recently when an agreement was renewed in 2019, and most infamously in 1997 when Canadian fishermen set up a blockade, effectively making hostages of passengers on an Alaska state ferry trapped for days in Prince Rupert, B.C., wrote Diane Selkirk in a 2019 article for BBC Travel.

The annual salmon run sustains scores of canneries and dozens of fishing towns and Indigenous villages along the coast and up myriad rivers in British Columbia.

Violations and disagreements continue in this maritime border dispute, but Gatling guns are no longer employed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada maintains a hotline for Canadians to report U.S. contraventions and infringements of salmon fishery agreements.

Advertisement