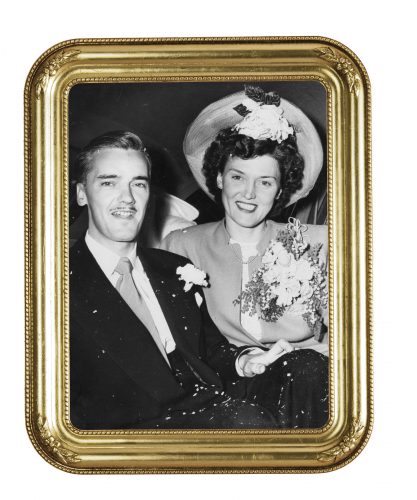

Helen Reeder was a Victory Bond volunteer when she met air force musician Harry Culley in Ottawa in 1942. [Courtesy of Joanne Culley]

My father, Harry Culley, never talked much about the war, I think because he felt he got off easy compared to many others. He seemed to be embarrassed that he wasn’t a heroic pilot flying missions over enemy skies, or a gunner at the front facing the Germans. He served as a musician, occupying, in his opinion, a lower rung in the military hierarchy.

Some of his fellow bandmates made self-deprecating comments about their status, such as Al Smith who said that he “fought Hitler with his French horn.”

During the Depression years, Harry cobbled together part-time jobs to make a living. By day he was a bookkeeper at a smoke shop on

Yonge Street in Toronto. By night he played saxophone and clarinet in downtown venues such as the Savarin Club and the Royal York Hotel.

When the war started, he happily traded in his precarious income for steady pay while serving his country. After passing the required musical theory and performance tests, he was accepted into the RCAF band on Aug. 22, 1942, and was sent to Ottawa for training at Rockcliffe.

While in Ottawa, the band played dances at the YMCA’s Red Triangle Club. Harry met my mother Helen Reeder, a volunteer hostess, at a Victory Bond fundraiser. While she served him ginger ale, they talked, and later began dating.

A young woman from the Prairies, Helen had grown up in a family of wheat farmers who experienced first-hand the severity of the Depression. Looking for a way out, she learned shorthand and typing by correspondence. When the war started, with the subsequent opening up of jobs for women, she passed the civil service exams and came to Ottawa to work at the Office of Munitions and Supply.

When Harry received word that the band would be going overseas, they became engaged.

Culley (at right) sits with his bandmates on a railway bridge in England. [Courtesy of Joanne Culley]

Letters

That much of my parents’ story I knew. But after their deaths, while clearing out a closet, I discovered an Eaton’s box filled with bundles of blue airmail letters tied with white satin ribbons. The 609 letters they had written to each other during the two-and-a-half years they were apart provided me with a fuller understanding of both their war experiences.

In August 1943, Harry travelled overseas with his bandmates on RMS Queen Mary, landing in Greenock, Scotland. From there they took the train south to Bournemouth on the English Channel, their home station and centre for Allied air forces, including about 12,000 Canadians. They became known as the RCAF Personnel Reception Centre Band No. 3, under conductor Flight Sergeant Stephen Vowden. Their mandate was to lift the spirits of soldiers and civilians alike through music.

The concert band was made up of about 30 musicians, and Harry also played alto and tenor saxophone in the smaller 12-piece dance band. They played in concerts, at dances, parties and parades, performing the popular songs of the day, including “Stardust,” “In the Mood,” “Stormy Weather” and “Moonlight Serenade.”

Helen mails a letter from Toronto to Harry overseas.[Courtesy of Joanne Culley]

A highlight for the dance band was accompanying Irving Berlin, who came to the Pavilion in Bournemouth in January 1944, when he sang some of his signature songs such as, “Oh! How I hate to get up in the morning.”

On Christmas Day in 1944, the dance band played at the Royal Bath Hotel in Bournemouth. Harry remarked that it was unusual to be playing jazzy versions of Christmas carols while looking out the window at a beach with tropical palm trees. This was just after famed band leader Glenn Miller went missing over the English Channel and they played several of his tunes in his memory.

The RCAF dance band performs. Harry (second from right) plays saxophone while Al Smith (back to camera) tinkles the ivories. [Courtesy of Joanne Culley]

Home front

After Harry left, Helen moved to Toronto to be closer to his parents and become familiar with the city as that’s where they’d be living once he returned. She found a position at the Toronto Transportation Commission, now known as the Toronto Transit Commission, performing a job that, at that time, would have been done by a man.

Nov. 14, 1943

Darling Harry, I’m on nights at the office this week which isn’t very much to look forward to…. I was on cash part of the time at my work last week and do you ever have to be on your toes! I lost 50¢ one day as I was short on the wicket. You see all the drivers come there to get tickets, and there’s such a rush all at once…. There are about fifty women drivers at the Motor Transport now.

Jan. 12, 1944

Next week I have to balance time sheets at work, so keep your fingers crossed for me eh? I’ve never done much clerical work before so find it rather hard. I’m not as nervous on the cash as I was though.

I was surprised to learn that my mother had the spunk to leave one job, move to a different city, and find another. While my two brothers and I were growing up, she stayed mainly at home, and didn’t go out to work until we were in high school.

Helen poses with colleagues at the Department of Munitions and Supply in Ottawa. [Courtesy of Joanne Culley]

Bombings

Despite what Harry said in later years, the band did face danger, especially while they were in London making recordings for the BBC that were broadcast for Allied troops.

During the “Little Blitz” in January 1944 and then around the end of June 1944, there was a continual barrage of V-1 and V-2 rockets exploding. Harry said as long as you could hear them you were alright; it was when there was no noise that you had to worry.

There was constant anxiety about where the next blast would be. During one close call, Harry and a bandmate dove for cover under the grand piano. The roof of the building where they rehearsed in London was blown off in one such hit, and he wrote that they hoped the rain would hold off until they were finished for the day.

The band was constantly on the move, on tours around the Midlands, up to Scotland, to Wales, Liverpool and many villages in between. They performed at important functions, such as the “Red Letter Day” when they played for King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, at the fourth anniversary of the Beaver Club in London, and at the opening of the new RCAF burn wing at the Queen Victoria Hospital in East Grimstead. They entertained the war-worn citizens of bombed-out Coventry in a field just outside of town.

The musicians worked hard, rehearsing daily, continually practising new pieces, studying theory and taking exams. They enjoyed their somewhat unique status of moving through the echelons, from staying in Nissen huts and lodging in small hotels such as the Atherstone in Bournemouth to living in luxurious private quarters in Meyrick Park.

The RCAF band often rehearsed and performed in the open air. [Courtesy of Joanne Culley]

Musical bond

Helen wrote to Harry two or three times a week, while he wrote once a week. Talking about music brought them together. She’d often write about what she was listening to.

Feb. 5 and Feb. 17, 1944

Dearest Harry, There doesn’t seem to be much on the radio now. Last night I enjoyed it though—Waltz Time, a symphony, Fred Waring, etc. Mart Kenny is playing out at the Pier tonight, but you can’t surprise me at the last minute and say we’re going this time. It makes me so happy to know that after you’ve been around so much you can sit down, read my letters and remember the little things we’ve done…. The future must bring us together always just as you say.

No. 3 Personnel Reception Centre Band, RCAF, parades past a reviewing dais where Vincent Massey, Canada’s High Commissioner to the United Kingdom, takes the salute. [Courtesy of Joanne Culley]

May 21, 1944

Darling Helen, Four of us played a dance at the American Red Cross about 25 miles from here last night. It was a kind of an Allied affair as four fellows formed the other section of the band and several Americans sat in for a session. This morning we were in a parade with all the jazz (flat hat, white belt, lanyard). They have a beautiful big parade square here. Rochester and Jack Benny are on [the radio] now. It’s almost like a Sunday night at home. I said almost. I’ve just realized what a wonderful invention the radio is. It seems like ages since I heard them at home with you.

I noticed a blot on one of your letters that looks suspiciously like a tear drop, sweetheart. It made me feel all funny inside when I realized you had been crying. Please don’t think of yourself as being alone angel, because you’re not really. We all love you and all I think about is you. All my love forever.

I knew my father as a quiet man, who rarely talked about his feelings, so I was surprised to see such eloquent expressions of love sprinkled throughout his letters.

Often, Harry’s letters were delayed, or he didn’t have time to write, with all the travelling around, and Helen feared the worst—that he’d been wounded, or that he’d fallen in love with someone else.

April 20, 1944

My Only Darling Harry, Yes, I understand when you say you can’t write at times. What is all important to me is the fact that you don’t forget me and you miss me. I suppose there are moments honey when we’re both thinking of each other at the same time…. Sometimes I feel you are so close that I could reach out my hand and touch you. Distance doesn’t make much difference, when there’s a strong love between us. I’m sure I love you even more than I did when you went away darling. Good night sweet.

While I was growing up, my mother was quite modest, always wearing a dress, even around the house, and never shorts. So, imagine my surprise when I learned she’d sent him a pin-up photo of herself in a bathing suit as a way to keep his spirits up. He thanked her for it, and said it made the other guys envious.

Newlyweds Harry and Helen in Toronto on June 5, 1946. [Courtesy of Joanne Culley]

Aftermath

Toward the end of the war, Harry wrote of encounters with newly released prisoners of war and burn victims. Even when he did complain of being cold sleeping in the Nissen huts, or of not tasting an egg for six months, he amended it by saying that he knew he could be a thousand times worse off.

While referring to a soldier who had been wounded in battle, he wrote, “Canada will be forever indebted to men like him. It makes me feel ashamed when I hear of cases like that really how little I am doing for the war effort.”

On Dominion Day in July 1945, two months after the war in Europe ended, there was a massed-band concert at Lincoln’s Inn Fields in London. Three bands—about 140 musicians—joined together under Martin Boundy, the head music director of the RCAF. Photos of the concert were published in Canada’s Weekly for the Forces and later in books about the war. Writing of it to Helen, Harry seemed proud to have taken part and to have been acknowledged by the 3,000 audience members for the contribution of music throughout the war.

When Harry returned home on Feb. 21, 1946, his reunion with Helen was as joyful as they had expected, culminating in their wedding on June 5.

Seventy-five years after the war, the music of that era has become part of our culture, being reinvented with each generation. No matter how they viewed themselves at the time, I think my father and the other musicians made a valuable and lasting contribution. And my mother and her cohorts did their part by paving the way for future women in the workplace.

Advertisement