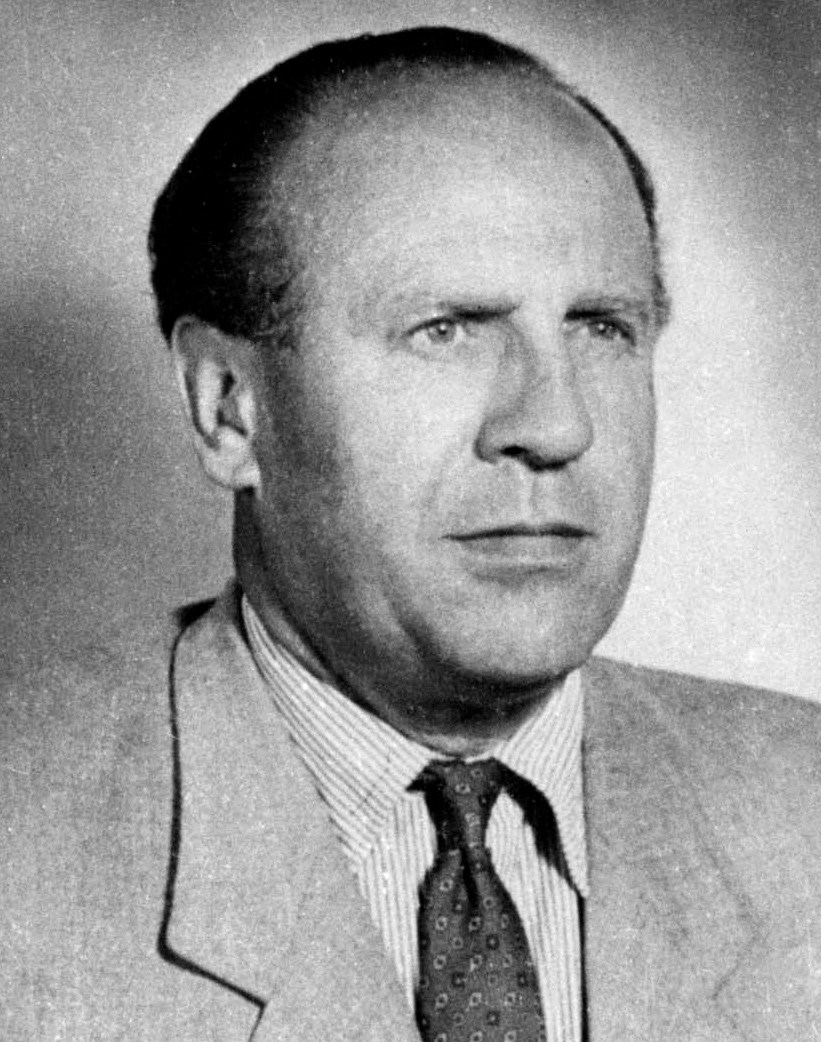

In order to save about 1,200 Jews from

certain death, German industrialist Oskar Schindler

feigned friendship with Nazi butcher Amon Göth.

Before becoming a wealthy industrialist, Oskar Schindler had served as a German military intelligence agent in his native Sudetenland (currently part of the Czech Republic). After the German invasion of Poland, he acquired ownership of a factory through a new law that forced Jewish entrepreneurs to sell their businesses. The factory produced enamelware, but as the war heated up, Schindler began producing munitions. Many of his employees were Jews living in the Krakow ghetto. At first they were paid—although at a lower rate than non-Jewish workers—but soon their salaries were garnisheed by the Waffen-SS.

In mid-1942, the Krakow ghetto was liquidated—its residents either executed, transferred to the newly constructed Plaszow Forced Labour Camp outside the city, or transported to death camps. Seeing innocent people packed into railroad freightcars and sent to certain death proved to be too much for this hard-drinking, womanizing and profiteering industrialist. He realized the persecution of the Jews was worsening. Now there was “plenty of public evidence of pure sadism, with people behaving like pigs,” Schindler later said, “I felt the Jews were being destroyed. I had to help them. There was no choice.”

It was February 1943 when Schindler met Plaszow’s new commander, Amon Göth. At the time, Schindler had about 900 factory workers. Most were Jews, marching four kilometres from the camp to their workplace. As Göth embarked on a reign of terror within the camp, Schindler acted to protect as many Jews as possible. He proposed building—at his cost—a barracks adjacent to the factory for his workers. By feigning friendly feelings for Göth, he managed to win the commander’s trust and agreement. Schindler’s barracks included kitchens, a laundry and showers. Conditions were humane and food adequate.

By the autumn of 1944, the Russians were closing on Krakow. Schindler gained permission to transfer his factory—and more importantly about 1,200 Jewish workers—to Sudetenland. A list of Jews from Plaszow was devised, large bribes were paid—particularly to Göth—and those selected were moved to the new factory. Ultimately Schindler’s entire fortune was spent saving these Jews from the clutches of the SS.

Escaping to western Germany at the war’s end, Schindler was supported by Jewish relief organizations until he received partial reimbursement for his financial loss. In 1963, Israel named him Righteous Among the Nations—an honour bestowed on non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust. Oskar Schindler died Oct. 9, 1974, in Hildesheim, Germany, and is buried in Jerusalem.

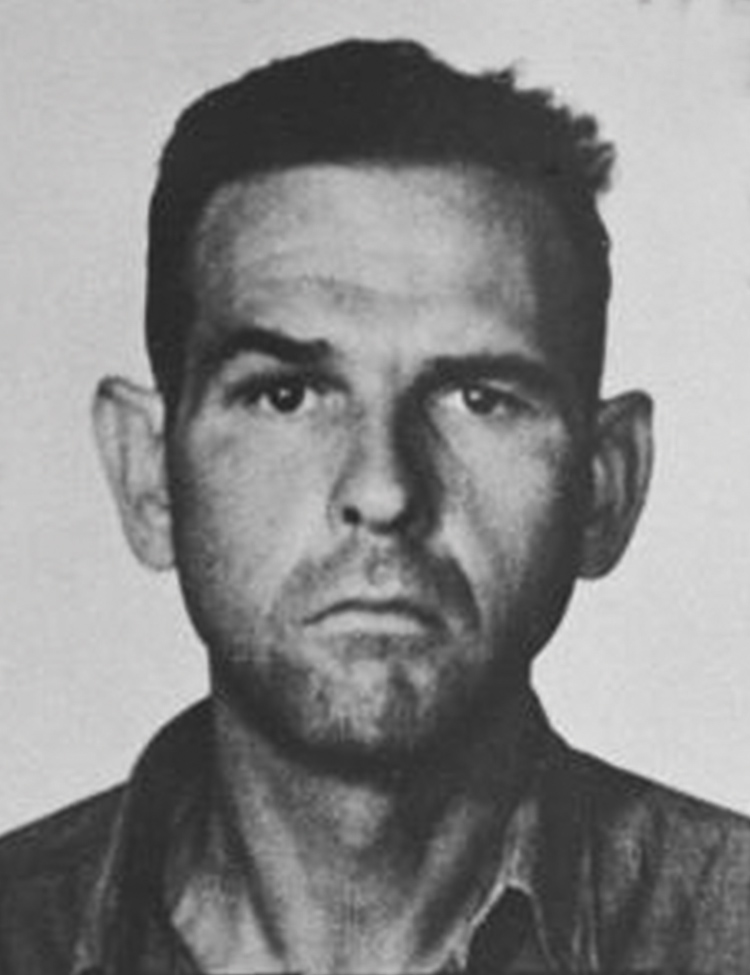

Before becoming the commandant of Plaszow Forced Labour Camp on Feb. 11, 1943, Amon Göth’s SS military career was spent entirely on implementing the Final Solution. In addition to running Plaszow, he oversaw the liquidation of the Krakow and Tarnow Jewish ghettoes. About 2,000 Krakow Jews were shot in place, roughly the same number imprisoned at Plaszow, and approximately 3,000 others shipped to Auschwitz for execution. Of Tarnow’s remaining 9,000 Jews, some 2,000 were transferred to Plaszow, 6,000 to Auschwitz, and the others murdered.

Everywhere, Göth confiscated gold, jewelry, money and other property. German regulations required such loot be turned over to the state, but Göth kept large amounts. Selling it on the black market supported his increasingly lavish lifestyle. Göth’s official Krakow residence was the scene of seemingly unending parties attended by SS officers and Göth’s cronies. Increasingly, he demanded that factory owners using Plaszow labourers pay bribes for their service.

Camp life was hellish and fraught with danger. Inmates were randomly flogged, often by Göth personally. At the slightest provocation—real or imagined—Göth shot prisoners dead, strangled others with his bare hands, or beat people to death. Hangings were used to intimidate. On numerous occasions his dogs, Ralph and Rolf, were goaded into savaging defenceless victims. “Never would I…believe that any human being would be capable of such horror, of such atrocities,” one inmate later testified.

In early 1944, Plaszow was re-designated a concentration camp. This change imposed some bureaucratic restraints on Göth, as executions and other severe punishments were supposed to be approved by Berlin. Göth, however, was able to circumvent the rules and the random killings continued. In the summer of 1944, with the Soviets closing on the camp, the corpses buried nearby were exhumed and burned to conceal the atrocities committed.

Göth’s excessive lifestyle led to an investi-gation by the SS police. He was arrested for large-scale fraud on Sept. 13, 1944, and imprisoned. Göth was extradited by the Americans

to Poland and tried for committing mass murder. He was sentenced to death on Sept. 5, 1946, and hanged at Plaszow eight days later. Göth died unrepentant, thrusting his arm up in a Nazi salute.

Oskar Schindler (second from the right) poses with a group of Jews he rescued during the Holocaust. The picture was taken in 1946, one year after the war ended.

Advertisement