A daguerreotype of Captain James Fitzjames taken in 1845 and sold at Sotheby’s in September 2023. The remains of Fitzjames, who commanded HMS Erebus, have been identified by DNA and genealogical analyses.

[Sotheby’s/Wikimedia]

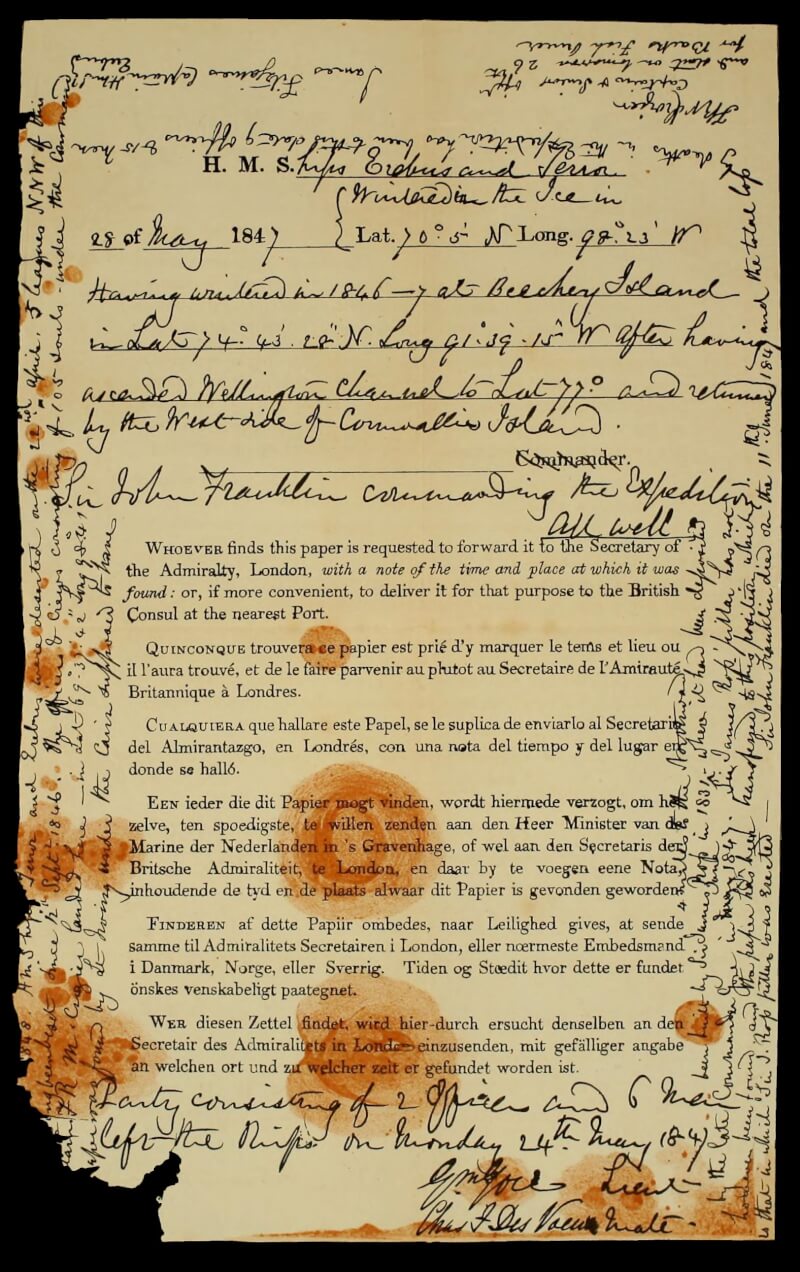

Scrawled in the margins of a preprinted Admiralty form, the so-called “Victory Point Note” bore two messages. The first, dated May 28, 1847, said the ships Erebus and Terror had wintered in ice, that Franklin was commanding, and all were “well.”

By April 25, 1848, however, the situation had deteriorated markedly.

“HM Ships Terror and Erebus were deserted on the 22nd April 5 leagues NNW of this having been beset since 12th Sept 1846,” it said. “Sir John Franklin died on the 11th of June 1847 and the total loss by deaths in the Expedition has been to this date 9 officers and 15 men.

“And start on tomorrow 26th for Backs Fish River.”

That second—and last—message was signed by the expedition’s second-in-command, Captain Francis Crozier of HMS Terror, and the skipper of HMS Erebus, Captain James Fitzjames.

Franklin’s quest to find a northwest passage to China ended there, in the ice and cold of what would become Canada’s Arctic. None of the expedition’s 129 members is known to have survived. Fitzjames and 12 others died near Erebus Bay, 80 kilometres from their abandoned ships.

The final communications from the ill-fated Franklin expedition, scrawled in the margins of a preprinted Admiralty form, the last of them dated April 25, 1848, and signed by Fitzjames and the expedition’s second-in-command, Captain Francis Crozier of HMS Terror. The so-called “Victory Point Note” was included in a 1998 exhibition at the Canadian Museum of History.

[National Maritime Museum, London]

The long-lost wrecks of Erebus and Terror were discovered in 2014 and 2016.

Now, after years of study, researchers at Ontario’s University of Waterloo and Lakehead University in Thunder Bay, have isolated DNA from a single molar and traced it to living relatives of Captain Fitzjames.

Recovered with 451 bones from at least 13 Franklin sailors, Fitzjames is just the second to be positively identified by DNA testing and genealogical analyses, and is the highest ranking of any crewman identified so far. John Gregory, engineer aboard Erebus, was identified by DNA testing in 2021, while the remains of several others were readily made over the years via period documents and other on-site evidence.

Belgian marine artist François Etienne Musin painted HMS Erebus still on open water, surrounded by icebergs, as crew shuffle boats across the Arctic ice.

[François Etienne Musin/Royal Museums Greenwich]

“The identification of Fitzjames’ remains provides new insights about the expedition’s sad ending.”

“We worked with a good quality sample that allowed us to generate a Y-chromosome profile, and we were lucky enough to obtain a match,” Stephen Fratpietro of Lakehead’s Paleo-DNA lab told Waterloo’s university newsletter.

Fitzjames’ mandible bears multiple cut marks, evidence his body was cannibalized after he died.

“The identification of Fitzjames’ remains provides new insights about the expedition’s sad ending,” said Douglas Stenton, adjunct professor of anthropology at Waterloo. “This shows that he predeceased at least some of the other sailors who perished, and that neither rank nor status was the governing principle in the final desperate days of the expedition as they strove to save themselves.”

Long considered morally reprehensible, cannibalism among stranded disaster survivors is not uncommon, yet remains an uncomfortable subject of conversation. It was a life-saving measure in the fate of 16 survivors of the October 1972 crash of Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571, who resorted to cannibalism during 72 days of sub-zero cold, starvation and an avalanche in a remote region of the Andes.

“It demonstrates the level of desperation that the Franklin sailors must have felt to do something they would have considered abhorrent,” said Robert Park, a Waterloo anthropology professor.

The Franklin story and the mystery surrounding the expedition’s fate, have been the subjects of books, articles, documentaries, even a TV horror series, “The Terror,” which incorporates cannibalism as one of its themes.

Said Park: “Meticulous archeological research like this shows that the true story is just as interesting, and that there is still more to learn.”

In their paper published in The Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, the researchers said they found the DNA to identify Fitzjames thanks to one particularly dogged fan of the AMC television show.

Fabiënne Tetteroo, a naval historian, parlayed her interest in “The Terror,” in which Fitzjames is played by actor Tobias Menzies, into a full-blown research project.

“After reading the late William Battersby’s book James Fitzjames: The mystery man of the Franklin Expedition (2010) I became very fond of Fitzjames and wanted to learn more about him,” Tetterroo writes on her website dedicated to James Fitzjames.

“It seemed that after Battersby, nobody had continued his Fitzjames research, so I took it upon myself to find answers to my questions. Because information on Fitzjames is so scattered, I thought, wouldn’t it be wonderful if there was a website where you can find everything Fitz?”

The researchers thank Tetterroo for “generously sharing the results of her investigations of Fitzjames’ family history and for her efforts to identify possible candidates for our Franklin expedition DNA research.” It was, they note, “through her efforts that we were connected with the descendant donor.”

An unbroken Y-chromosome DNA match was made from a living descendant of Fitzjames’ great-grandfather James Gambier. That donor, Nigel Gambier, is second cousin five times removed to Fitzjames.

The wreck of Fitzjames’ ship Erebus was discovered on the seabed in Queen Maud Gulf by Parks Canada marine archeologist Ryan Harris.

[Parks Canada]

Raised by a pastor and his wife, Fitzjames’ true family ties—for years, the subject of wild speculation—were unconfirmed until Battersby unlocked the mystery in 2010.

Fitzjames had been tapped by John Barrow, second secretary to the Admiralty and a long-time supporter, as potential leader of a polar expedition, but was instead named captain of Erebus under Franklin.

Raised by a pastor and his wife, Fitzjames’ true family ties—for years, the subject of wild speculation—were unconfirmed until Battersby unlocked the mystery in 2010. His mother has never been identified. He was the illegitimate son of James Gambier, whose family was prominent in the Royal Navy. Among others, Gambier’s cousin was an admiral and his father a vice admiral.

Fitzjames joined the senior service as a volunteer at age 12, initially serving under yet another Gambier aboard HMS Pyramus, a frigate. He eventually graduated to midshipman on HMS St Vincent, flagship of the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean fleet.

By 20, he had served on multiple ships and made lieutenant.

Loaded with charm and charisma, he has been described as handsome, personable and skilled in winning the confidence of superiors, despite the stigma surrounding his origins. He was also highly intelligent and well educated.

He distinguished himself during the ill-conceived Euphrates Expedition, a precursor to the creation of the Suez Canal. Before that voyage even sailed, Fitzjames dove into the River Mersey fully clothed to rescue a drowning man. He was awarded a silver cup and the Freedom of the City of Liverpool for his courage.

The expedition, however, was plagued by rugged conditions, politics, disease, storms and loss of life. It was eventually halted by the British government after one of its two steamers sank and the other lost its engine.

Fitzjames volunteered to take the ship’s packet of India Office mail 1,900 kilometres across what is now Iraq and Syria to the Mediterranean coast and from there to London.

After many adventures—he was nearly kidnapped and trapped in a besieged town—Fitzjames arrived in London, where he would reunite with surviving expedition members as they straggled back.

In 1984, anthropologist Owen Beattie exhumed one of the Franklin bodies buried on Beechey Island and found a pristinely preserved member of the expedition named John Torrington. According to letters from the crew, the 20-year-old died Jan. 1, 1846, and was buried in five feet of permafrost.

[Brian Spenceley]

Fitzjames is believed to have died in May or June 1848, alongside Gregory and at least 11 others south of Victory Point.

He later served with distinction as a gunnery officer on HMS Ganges in the Egyptian-Ottoman War between 1839 and 1840, then as gunnery lieutenant on HMS Cornwallis, flagship to the force fighting the First Opium War of 1839-42. It was during this stint that he led the decisive assault on the walls of Zhenjiang.

Thanks to backing from Barrow at the Admiralty, Fitzjames was awarded an accelerated promotion to commander and the brig-sloop Clio. He joined the ship in Bombay and cruised the Persian Gulf performing diplomatic duties before returning to Portsmouth in October 1844.

Barrow was a prime mover of the Franklin expedition. He pushed for Fitzjames to be appointed to lead it and another friend, Edward Charlewood, to be second in command. But Barrow couldn’t persuade the Admiralty board of their merits. Fitzjames lost out due to his relative youth. Still, he was awarded Erebus.

Crozier assumed command after Franklin died; Fitzjames became his second.

The ships sailed from Greenhithe, England, on May 19, 1845. They were last seen by Europeans in late July, when two whalers sighted them in northern Baffin Bay.

Fitzjames is believed to have died in May or June 1848, alongside Gregory and at least 11 others south of Victory Point. A ship’s boat and human remains were discovered in 1861 by Inuit, who provided the first reports of cannibalism.

The site was rediscovered by Anne Keenleyside, a Canadian bioarcheologist, in 1993. Known as Site NgLj-2, the remains of those found there now surround a memorial cairn, marked with a commemorative plaque.

Advertisement