John McCrae [Wikimedia]

A veteran of the 1899-1902 Boer War, the Guelph, Ont., physician shipped out to South Africa with the imperialistic ideals of poet Rudyard Kipling in his head.

“I shall not pray for peace in our time,” he once wrote to his mother, Janet Simpson Eckford McCrae. “One campaign might cure me—but nothing else ever will.”

A year of overseas service with ‘D’ Battery, Canadian Field Artillery, did, in a sense, cure him. Largely gone were the romanticized beliefs that war was an adventure, replaced by the realities of life and death on South Africa’s unforgiving veldt.

But McCrae still believed in serving one’s country, a notion that compelled him to enlist again after the outbreak of the First World War in the summer of 1914.

Now a medical officer with 1st Artillery Brigade, Canadian Field Artillery, the experienced doctor soon found himself at the 1915 Second Battle of Ypres. There, the Germans attempted to eliminate the Allies’ Ypres salient by any and all means possible, including through the first widespread use of chlorine gas.

McCrae’s surgical station was situated about eight kilometres behind the front lines, itself nestled in the reverse slope of an embankment to protect against incoming shells. The dugout quickly became inundated with the wounded.

“Of one’s feelings all this night—of the asphyxiated French soldiers…I could write, but you can imagine,” he penned in a diary entry addressed to his mother.

Hauntingly mutilated patients, some without limbs and others seemingly drowning from the effects of gas, continued to pour into the station as the smell of blood and excrement only increased with each passing hour. McCrae’s eyes wept from the chlorine fumes, which clung to uniforms long after the cloud had passed.

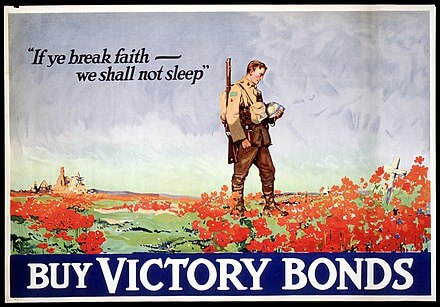

“If ye break faith – we shall not sleep” war poster created in 1918; from the Archives of Ontario poster collection. [Wikimedia]

Despite feeling inclined to discard the stanzas, McCrae’s friends convinced him to submit them for publication.

Such was the medical officer’s life for the next two weeks. By that stage, the Canadians, having held the line against all odds, had mostly been relieved at Ypres and cycled into reserve. However, on May 2, 1915, McCrae learned that his dear friend, Alexis Helmer, had been hit by a high explosive shell and killed. He was blown apart.

McCrae was devastated by the loss. On rare breaks, sitting outside his dugout and staring at a nearby makeshift cemetery, he began composing a 15-line poem.

The words, written as a plea from fallen comrades, immediately resonated.

Despite feeling inclined to discard the stanzas, McCrae’s friends convinced him to submit them for publication. The periodical named The Spectator rejected the verse, but the satirical magazine Punch accepted it.

McCrae’s “In Flanders Fields” was published on Dec. 8, 1915, becoming the most famous English-language poem of the war. It was eventually used in recruitment drives, Victory Bond appeals and election campaigns.

McCrae, already a published writer, found only minimal solace in his poem’s new-found popularity, instead focusing on saving lives for the next three years. He died of pneumonia and meningitis on Jan. 28, 1918, at just 45 years old.

Today, “In Flanders Fields” has become—and will almost certainly forever be—intertwined with Remembrance Day across Canada, the U.K., and beyond.

Advertisement