Reinhard Hardegen. [Piccy]

He ranked No. 24 on the list of Germany’s Second World War U-boat aces but, in sheer chutzpah, few could compare with Reinhard Hardegen.

Hardegen died in Germany on June 9 at age 105, the last of a breed both reviled and respected for preying on all manner of Allied ships from beneath the waves—a cloak of invisibility that offered them large measures of both risk and reward.

In a service in which 784 of 1,156 unterseeboots ended up at the bottom of the ocean, and 28,000 of 40,900 crew were killed, Korvettenkapitän Hardegen was more than a survivor.

In just five patrols, he sunk 22 ships, accounting for 115,656 tons, and damaged four others. He was a showman who conducted war in view of Florida beachgoers, a naval officer who rejected Nazism as early as 1942, and a bold defender of his service who risked Adolph Hitler’s wrath by citing der führer’s strategic flaws to his face.

The bulk of Hardegen’s score came on two patrols during Operation Drumbeat, which targeted North American coastal shipping after the United States joined the war in December 1941.

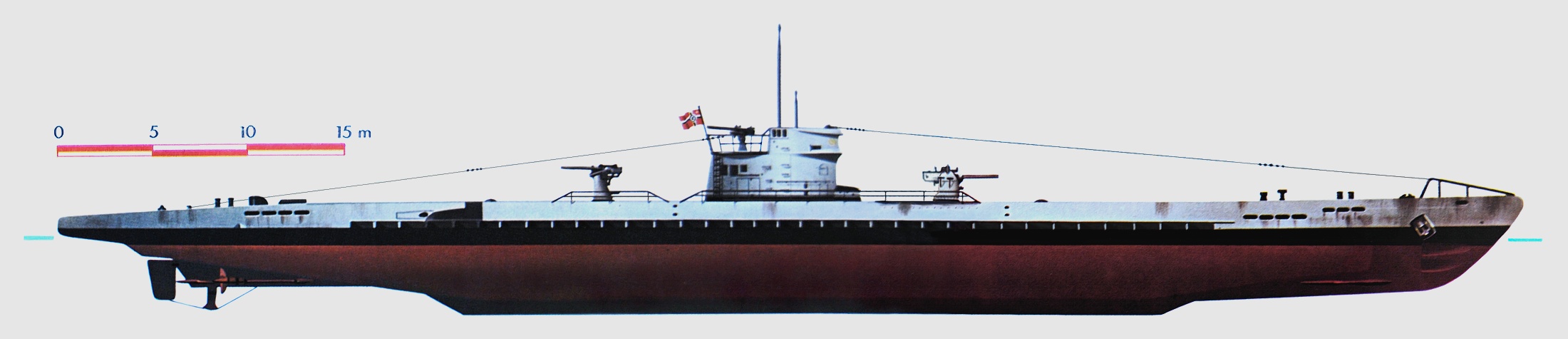

Commanding U-123, he effectively launched the mission off Nova Scotia on Jan. 12, 1942, three weeks after departing Lorient, France, and days ahead of schedule, by sinking the British freighter Cyclops at a cost of 98 merchant lives.

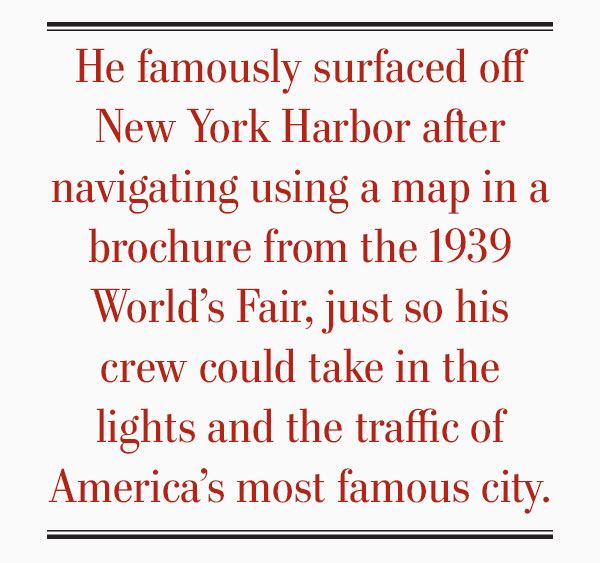

Nearly 400 Allied ships would go down during the campaign, 19 of them credited to Hardegen over two patrols. Then a kapitainleutnant—equivalent to navy lieutenant—he famously surfaced off New York Harbor after navigating there using a map in a brochure from the 1939 World’s Fair, just so his crew could take in the lights and the traffic of America’s most famous city.

“I cannot describe the feeling with words, but it was unbelievably beautiful and great,” he later wrote. “I would have given away a kingdom for this moment if I had one. We were the first to be here, and for the first time in this war a German soldier looked upon the coast of the U.S.A.”

There were no mandatory blackouts along the eastern seaboard at that time. Hardegen and his fellow U-boat commanders spent weeks at sea targeting unprotected tankers and freighters silhouetted by the glow of city lights.

Years later, he told the Charlotte Observer he was “very surprised” at the lack of maritime defences—“no blackouts, no dimming, nothing.” He and others described America’s Atlantic coast as a “shooting gallery.”

From NYC, Hardegen sank ships all down the eastern seaboard. He torpedoed the tanker SS Gulfamerica off Jacksonville, Florida, on April 11, surfacing and positioning U-123 between the flaming hulk and the beach before executing a coup de grace with his deck gun. The ship drifted seaward and sank several days later.

“All the vacationers had seen an impressive special performance at [President Franklin D.] Roosevelt’s expense,” he wrote in his log. “A burning tanker, artillery fire, the silhouette of a U-boat—how often had that been seen in America?”

The move almost cost him, however. As roads to the beach jammed with rubberneckers, 19 Gulfamerica crew died and beachgoers scrambled into rowboats to rescue survivors, the skipper lingered—too long, it turned out.

Forces converged on U-123, including aircraft from nearby bases, along with the American destroyer Dahlgren. One plane dropped a flare directly over U-123. Hardegen crash-dived, hitting bottom at just 20 metres.

Dahlgren had them on sonar, closed in and dropped six depth charges.

The boat took “a terrible beating,” Hardegen logged. “The crew members fly about, and practically everything breaks down. Machinery hisses or roars everywhere.”

Trapped in shoal waters, his boat severely damaged, Hardegen was sure they were cooked. He ordered his crew to prepare to abandon ship and distributed the rotors from his enigma cipher machines among the officers to dispose of randomly. He ensured the documents, printed with water-soluble ink, were left to soak.

Scuttling charges were set and escape apparatus were handed out.

All for naught: Dahlgren’s skipper concluded he had not made a U-boat contact after all and abandoned the attack. An incredulous Hardegen waited, surfaced and limped to deeper water, where he took up on the seabed again to rest and repair.

U-123 showing the wounded badge emblem leaves the Port de L’Orient on June 8, 1941. [Bundesarchiv, Bild 101II-MW-4260-37 / Kramer / CC-BY-SA 3.0]

For seven tankers the hour has passed,

The Q-ship hull went down by the meter,

Two freighters, too, were sunk at last,

And all of them by the same Drumbeater!

In his 1990 book Operation Drumbeat, author Michael Gannon said the campaign’s impact on the supply chain “constituted a greater strategic setback for the Allied war effort than did the defeat at Pearl Harbor.”

“In terms of [U.S.] raw resources and materiel,” he added, it was “the costliest defeat of World War II.”

About 5,000 merchant mariners died in the U-boat offensive, which fell off later in 1942 as armed convoys and advanced technologies diminished their effectiveness.

Already a recipient of the Knight’s Cross, Hardegen was summoned by Hitler so he could present him with Oak Leaves personally. He was invited to dine with him, sitting at his right.

Hardegen told an interviewer in 1994 that he had been briefed by other Knight’s Cross recipients on what to expect. They said Hitler wanted to hear straight talk about how the war was going.

“I had a list of concerns I wanted to bring up, from morale, torpedoes, and how we were being used,” he recalled. “Many party officials and military officers greeted me, and then I met the führer. He was very jovial and kind, he started by asking me to join him for lunch after the award of the oaks.

“He told me he does not always seem to get an accurate view of what is happening on the fronts, and wanted my opinion of the U-boat war.

“I told him of all of my concerns, regarding defective torpedoes; wolf packs needed to be tripled in size to be effective, and how a lack of effective organizing was hurting morale.”

He said Hitler—who was notoriously dismissive of the kriegsmarine—agreed, and told him Germany was caught “completely unprepared” for the type of war it was fighting, that his generals were doing their best but were in unfamiliar territory.

“He shouldered the blame, saying he never wanted this war, and only wanted Germany to have her rightful land and freedom. I told him that was irrelevant now; since we are in the war, we must fight to win it.

“Some of his staff were not impressed.”

Other reports said he also told Hitler that German leadership was too focused on the eastern front at the expense of the west—and the Battle of the Atlantic. They said he was reprimanded for his candour.

“I believe we could have won if we would have focused solely on U-boat construction early on,” Hardegen told his interviewer in a sentiment echoed by numerous historians. “In 1939, I was appalled that we were going to war with such a small U-boat fleet.

“If, say, by 1940 we would have been able to field 1,000 boats instead of 26, we could have sunk every Allied ship, and overwhelmed any convoys.”

Instead, he said, Germany was overwhelmed by Allied production. “They could make more ships in a month than we could make in a year. They developed new measures to combat us, and we developed ours too late.”

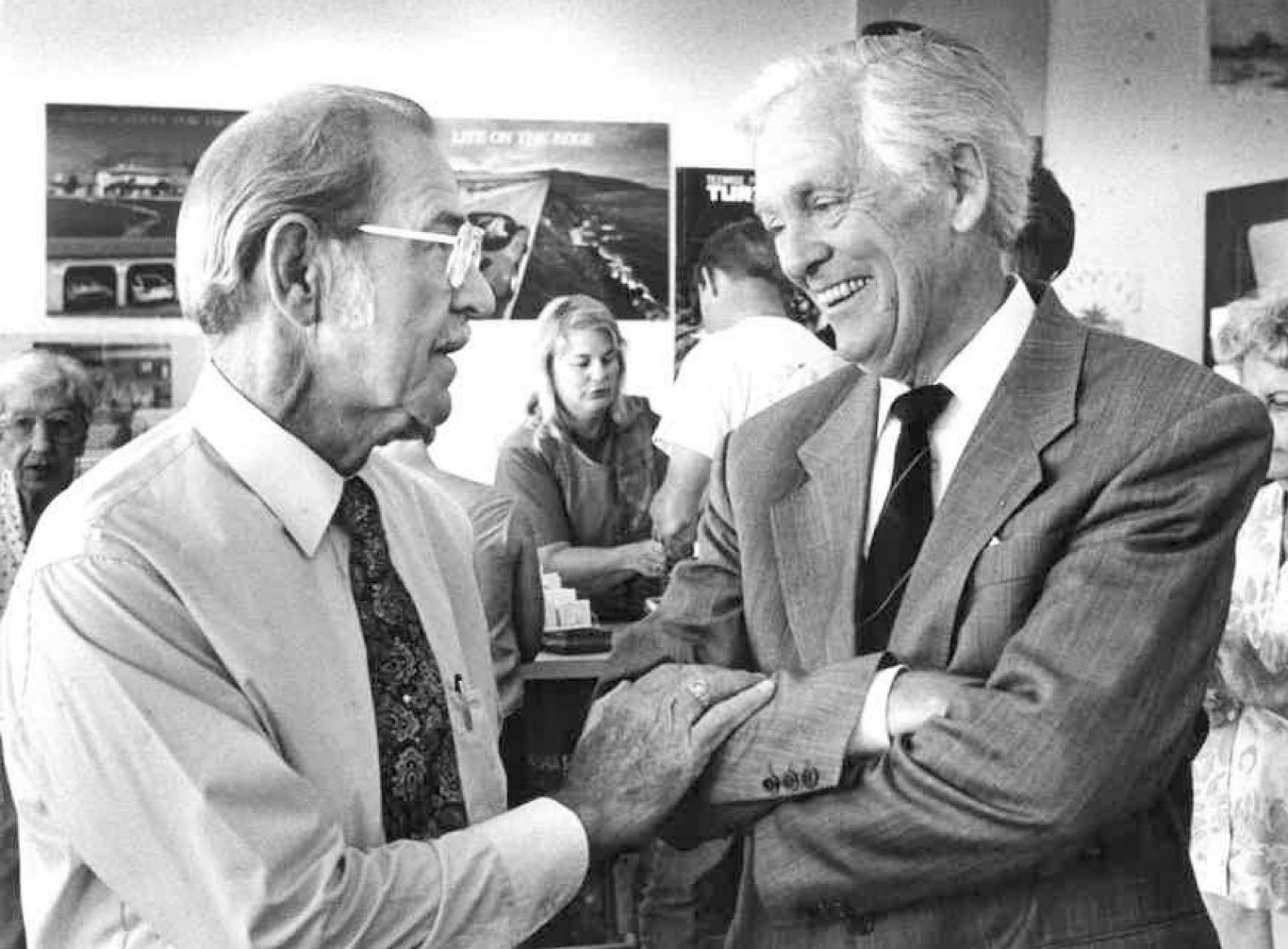

Author Lee Watson (left) talks with Hardegen at a book signing in 1990. Watson was aboard the Tanker SS Gulf America in 1942 when Hardegen sank the vessel off the coast of Jacksonville Beach as Captain of U-123. [Florida Times]

He went into the heating oil business—representing, among others, Texaco, whose ships he had sunk. He visited the United States many times, conversing with survivors and veterans regularly.

Advertisement