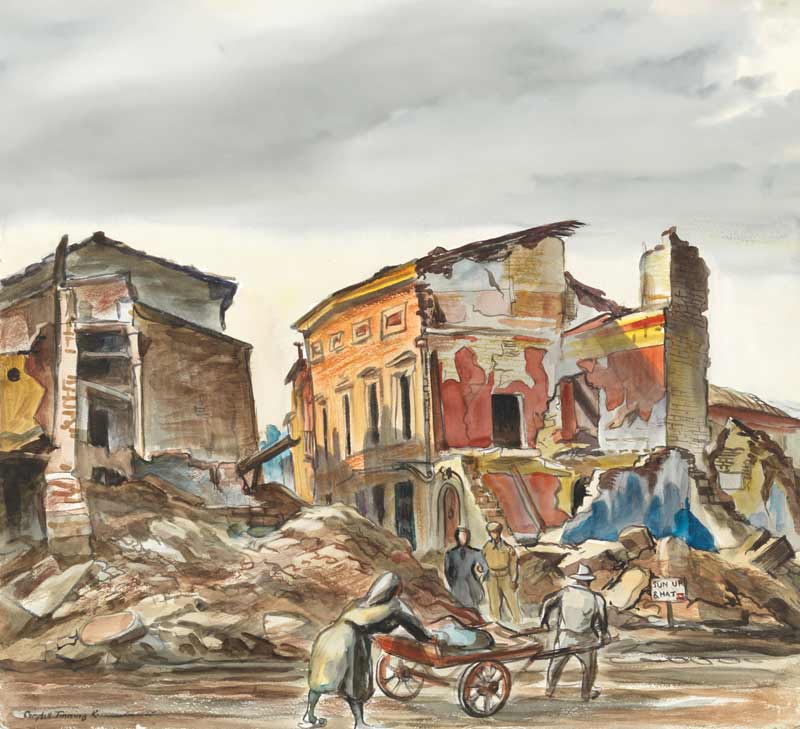

Captain George Campbell Tinning depicts Ravenna, Italy, in February 1945. [Captain George Campbell Tinning/CWM/19710261-5568]

On the night of Nov. 20-21, 1944, 33-year-old Canadian Captain Dennis Healy slipped into a rowboat alongside an Italian partisan leader. Healy’s mission was to support partisans operating behind German lines from a base situated on an island that was surrounded by a large swampy area to the north of Ravenna.

Heavy squalls immediately forced the party back to a beach outside Cervia—where I Canadian Corps was headquartered. Thwarted again the following night, it wasn’t until Nov. 25-26 that their small group rowed off to spend seven hours “tossing…on a lonely sea” before turning shoreward just north of Porto Corsini—the large port complex outside Ravenna.

Months earlier, partisans led by Captain Dennis Healy (right) liberated the town.[Courtesy Sean Healy]

Tensely the men looked unsuccessfully for a signal from a shore party that was to meet them. Finally, as Healey later wrote, they grounded the boat and waded ashore “with weapons cocked.” Out of the darkness came “the shrill cry of a nighthawk.” An oarsman replied in kind “and we were soon surrounded by a band of armed cut-throats who spirited our cargo away into the night and lifted our craft on to an awaiting ox-cart. No word was passed. A few minutes later, we were threading our way through the dunes towards the partisan camp…. A rear party worked until one hour before dawn covering the tracks we had left, then women and children…went down at first light to finish the job.” Healy’s mission, which would culminate in the partisans liberating Ravenna, had begun.

“Bulow knew exactly what was wanted” and, when the time came, would strike “with the utmost vigour and determination.”

Captain Healy hoists a Panzerfaust near Ravenna.[Courtesy Mark Zuehlke]

Dennis McNeice Healy was an unlikely guerrilla operative. Born in Bethune, Sask., he followed an academic path that led to heading up the French department at Edmonton’s University of Alberta. After the war started and he joined the army, Healy’s fluency in French, Italian, Spanish and basic capacity in German and Dutch had him attached to I Canadian Corps headquarters as an intelligence officer. Generally, he spent his time analyzing documents to assist Lieutenant-General Charles Foulkes in directing Canadian operations in Italy. There had been no training in conducting covert operations or working with resistance fighters.

Healy, however, was present when the Italian partisan leader was brought to corps headquarters early on Nov. 20. A couple of days earlier, Lieutenant Arrigo Boldrini—who went by the nom de guerre Major Bulow—had journeyed by rowboat past the German lines. Met by U.S. Office of Strategic Service (OSS) operatives, Bulow was escorted to British Eighth Army headquarters.

At first, the OSS had been unsure what to make of the “scrawny lieutenant in his late twenties, the son of Romagna peasants.” Their doubts were quickly swept aside when Bulow professionally used operational maps to brief the Eighth Army commander.

Bulow told him there were 900 partisans hidden in the swamps. They were designated by the Italian military serving with the Allies as the 28th Garibaldi Brigade. Bulow said his men were ready to liberate Ravenna from the Germans.

While some officers, like Bulow, had served in the Italian army and turned against the Germans when Italy surrendered to the Allies in September 1943, most partisans were local men and women with no formal training.

Bulow said that if the Allies worked closely with the partisans, the city of Ravenna could be spared heavy air, sea and land bombardment to oust the German occupiers. Ravenna’s numerous Renaissance cathedrals that housed one of the world’s finest collections of mosaic artwork, Bulow said, must be saved from destruction.

The Brits passed Bulow on to the Canadians. It was Foulkes’ forces who were closing on Ravenna and would either work with the partisans or not. Bulow advised the Canadian command that the partisans controlled the marshes and could fight the Germans from that stronghold. But they desperately needed arms, ammunition, clothing and food.

Deciding someone must work directly with Bulow, Healy was assigned the task. The partisans already had an OSS radio team in place, so Healy would use them to report the positions of German headquarters, strongpoints and any other information that would assist the Canadian advance on the city.

Foulkes, Bulow and Healy spent several hours planning, which Healy credited with developing “mutual trust and confidence” and ensuring “Bulow knew exactly what was wanted” so when the time came, they would strike “with the utmost vigour and determination.”

Italian partisan leader Lieutenant Arrigo Boldrini, nom de guerre Major Bulow, speaks with Italian Prime Minister Ivanoe Bonomi and Minister of War Alessandro Casati in March 1945. [Mondadori Portfolio/Getty/141558134]

Healy’s first impression of the partisan camp was that so many essential things were lacking, “I doubted whether we could be effective as a harrying force unless supplies could be sent in before we were ordered into action.”

There was little ammunition and the only lubricant for guns was Brilliantine, which worked poorly or not at all. There was no means of caring for sick or wounded and evacuating them was impossible.

“The men were half naked and it looked as though the cold and damp would greatly reduce our fighting strength unless warm clothing and blankets could be provided,” noted Healy.

He sent corps a shopping list, but foul weather made sea or air delivery impossible. Dribs and drabs were finally provided.

The camp situation on the island, Isola degli Spinaroni, meant it could only be approached by crossing flat, marshy ground that offered good fields of fire for the defence. But if the camp were to be discovered, the Germans could shell or mortar it while the partisans could offer no effective response.

Healy sought to create defensive shelter and firing positions by having the partisans dig slit trenches and other fortifications from which they could fight.

“The partisans,” he reported, “muttered darkly about ‘regular soldier nonsense’ but complied.”

Healy’s presence attracted a stream of reconnaissance reports from many sources.

“No task is more trying than that of attempting to obtain accurate military intelligence from untrained observers. It required the patience of an angel, an inexhaustible supply of cigarettes and a fund of good humour,” noted Healy.

As the Germans treated every adult male and most females as potential partisans subject to detention, Healy relied on “the aged and infirm” to gather intelligence and serve as runners between partisan strongholds.

Partisan observers were sent out, but they moved only at night and in areas each knew well. Observers generally hid in houses through the day, sending women and small boys to gather intelligence. The next night, the information would be carried back to camp.

“These missions were not without hazards,” said Healy, “several partisans failed to return.”

Sorting through the intelligence, Healy believed his findings were accurate and important, but also that if left to just their own devices and lacking an army intelligence officer working “at source,” everything would have “to be eyed with suspicion.” Healy’s presence enabled him to determine where reliable and unreliable intelligence originated.

As the intelligence picture Healy was providing to corps enabled the Canadians to shape a plan for seizing Ravenna, he and Bulow focused more on taking the fight to the Germans. The first action he participated in was a raid on an outpost outside Porto Corsini on the night of Nov. 29-30.

The intention was to inflict casualties and goad the Germans into bringing reinforcements out of Ravenna. Bulow’s plan for taking the city explicitly entailed harassing the Germans at the port to the point that the badly overextended enemy would opt to withdraw from Ravenna and reinforce the garrison at the more strategically significant transport hub. The enemy did as expected.

In small boats, a force of 150 partisans traversed a “maze of canals…and finally landed at a point where we could hear the Germans singing in their billets some 500 yards away,” reported Healy.

Crawling to within 150 metres, the partisans gunned down the sentries and for a minute it seemed the Germans could be overrun. Then three machine guns opened fire from the left flank. Bulow directed fire their way and two of the guns were silenced. The third gun crew, however, continued firing sporadically, but with what Healy thought was little conviction. With the Germans having withdrawn to prepared positions, the attack foundered, and Bulow ordered a retreat.

“No task is more trying than that of attempting to obtain accurate military intelligence from untrained observers. It required the patience of an angel.”

Canadian recce troopers speak with Italian partisans in January 1945.[Captain Alex M. Stirton/DND/LAC/PA-173569]

On the Canadian front, meanwhile, the time was ripe to launch assaults from the south and west toward Ravenna. With Canadian and attached British troops closing in, the Canadian command signalled Healy on Dec. 3: “Believe all enemy will leave Ravenna tonight and tomorrow. Unleash the partisans. All here full of praise for work you and partisans are doing.”

Bulow and Healy had already gone into action the day before with a flurry of ambushes, roadblocks and attacks on prepared positions. Two German garrisons in Porto Corsini were wiped out—eliminating forces tasked with demolishing harbour facilities. Other outposts were so harried that the Germans in them fled in small groups into the marshes to escape westward. Most of these groups were hunted down and eliminated by the partisans who knew the swamps intimately.

“We dominated the area in which we had been ordered to operate,” said Healy, “and so infuriated the enemy that he saw fit to do us the honour of a counterattack with tanks, [self-propelled guns], infantry and mortars at a time when he could ill afford any punitive expedition.”

By the time of the Dec. 4 counterattack, Healy estimated the partisans had killed 75 to 125 Germans, wounded 30 to 50, and had 25 prisoners waiting to hand over to the Canadians.

The armour-supported German response should have cut the partisans to pieces. Withdrawing to prepared defensive positions offered some protection. But they had no weapons with which to fight armour. Improvising, they planted previously retrieved German mines that blew up an enemy half-track and killed 20 of its occupants while wounding two other men.

Still, ammunition was running out and every partisan was up front fighting. Healy realized that when the battle started, there was no way to hold any partisans back in reserve. The partisans, he reported, fight “with dead earnest…until they drop in their tracks of weariness and fatigue.”

Tanks of the 5th Canadian Armoured Brigade move through Ravenna, Italy, in January 1945. [LAC/PA-173533]

By this time, the partisans had been fighting for six days and nights without pause and hardly any food.

Unable to overrun the resistence members, the Germans retreated to the northwest, away from Ravenna. The way was now open for the partisans to enter the city. Bulow had anticipated this moment and issued instructions to the populace to begin marking where mines had been laid, to post sentries on the minefields, and to clear felled trees and other debris from the main thoroughfares. Partisans inside Ravenna began policing the town and rounding up German sympathizers and Italian fascists.

By the time Canadian and British troops entered the city late on Dec. 4, they found it quiet and under partisan control. A staff officer at corps headquarters, unsure what was happening, signalled Healy: “Our troops report that Ravenna is free. Can you confirm it?”

Healy duly replied that he and Bulow had brought most of the Garibaldi Brigade into the city where Foulkes had ordered it concentrated for rest and relief.

Healy’s days with the partisans were ending. He considered it “a privilege to associate with the partisans of Ravenna who are brave and determined…They fought hard and well. Their contribution is difficult to assess…but two things are sure: Their assistance increased the number of enemy casualties and diverted the enemy’s attention at a time chosen by [Foulkes].”

The partisan actions were credited afterward as having saved Ravenna from Allied bombardment. For his part in its liberation, Healy was declared an Honorary Freeman of Ravenna on Feb. 11, 1945. He was also made a Member of the Order of the British Empire for having “showed great personal bravery” and serving “as an inspiration to the partisans.”

After the war, Healy returned to university teaching. He died on Nov. 11, 1984, in Victoria. On June 21, 2021, a plaque honouring Healy, mounted on a restored partisan building on the island that served as the partisan base, was unveiled by Ravenna’s historical organization.

Advertisement