On a thankless mission to protect citizens and keep warring factions apart, ingenuity and improvisation were the Canadian way

Orphaned children stand outside the gate of the United Nations Protection Force compound in the enclave of Srebrenica in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Civilians in the Balkans faced years of genocide, siege and massacre. [Betastock/Alamy/2A3WB7K]

Tasked by the United Nations in 1991 with rewriting the rules of engagement governing its evolving peacekeeping operations, then-major-general Lewis MacKenzie did what he could within the confines of Chapter 6 of the UN Charter.

The chapter sets out onerous limitations on UN forces to bring about the peaceful resolution of disputes. They essentially prohibit peacekeepers from defending anyone but themselves. Chapter 7, on the other hand, authorizes the use of military force.

A few months later, the much-travelled MacKenzie was commanding the UN’s first peacekeeping mission to the Balkans, the UN Protection Force. They were based in the city of Sarajevo, smack in the middle of warring ethnic factions with little to no regard for human life. There was no peace to keep.

It was then that MacKenzie did what any good Canadian soldier would do in such a circumstance: he improvised, and came up with what he calls his Chapter 6.5 rules of engagement.

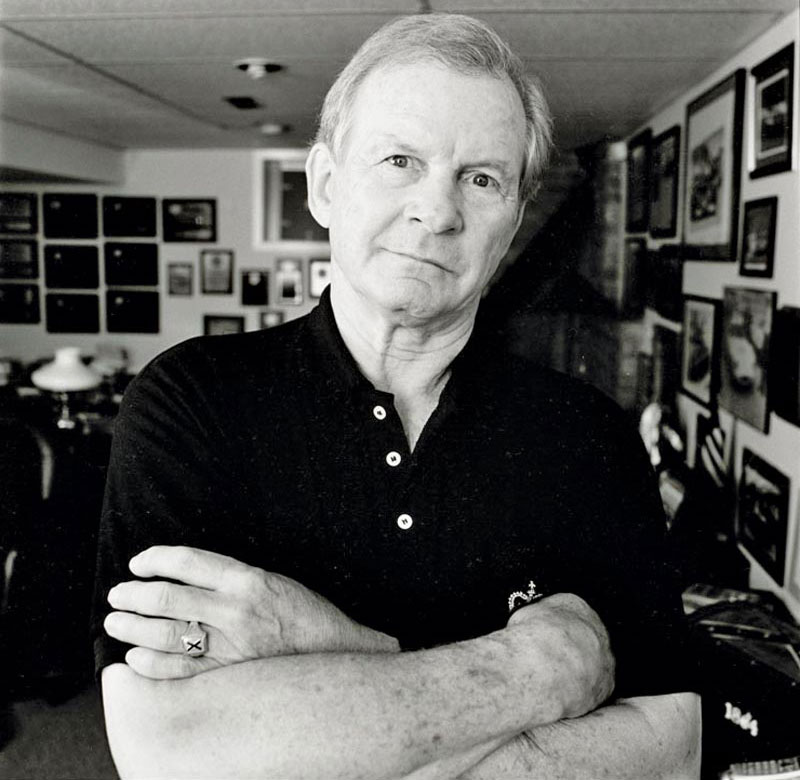

Retired major-general Lewis MacKenzie was for years the Canadian face of UN peacekeeping. [LAC/4913862]

In the newly declared republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Muslim Bosniaks, Orthodox Serbs and Catholic Croats were at war. Well-armed and backed by neighboring Serbia, the Bosnian Serbs had laid siege to Sarajevo. They targeted Muslims mainly but also killed Croats as well as their own with rocket, mortar and sniper attacks that went on for 44 months.

The Bosnians were setting up positions near vulnerable targets such as schools, hospitals and UN encampments and checkpoints. They would inevitably draw fire from the other side and UN forces would respond, doing their dirty work for them.

Residents of Sarajevo take cover from sniper fire behind an UNPROFOR armoured vehicle in 1993. [Danilo Krstanovic/Reuters/Alamy/2D1GJ50]

MacKenzie was having none of it. His repeated pleas to the Bosnian defence minister and other officials had been ignored.

“When that didn’t happen after a day or two, then the next thing would be a threat that ‘if you don’t remove them, then I will have my people kill your people.’ In every case, in that situation, they moved,” said MacKenzie in an interview with Legion Magazine.

“Half of those people didn’t deserve to be called snipers. They were just thugs, drunks with guns.”

Finally, MacKenzie came up with the ultimate solution to the problem. Without informing his political masters back in Ottawa or New York, he authorized so-called “black ops”—nighttime patrols to root out these ill-placed positions.

The images of Sarajevo, which just eight years earlier had hosted a Winter Olympic Games, were unforgettable to a western television audience still rejoicing in the breakup of the Soviet empire. The city and its citizenry were collapsing before their very eyes. Snipers were picking off innocent civilians in the streets.

“Half of those people didn’t deserve to be called snipers,” said MacKenzie. “They were just thugs, drunks with guns.

A Bosnian Army sniper peers through his rifle scope in the besieged capital city of Sarajevo. [Mark Milstein/Alamy/D50102]

“Somebody would fire down on the Van Doos at the airport; our marksman would see the sniper, like an idiot with his gun out the window in a three-storey building or something, and he’d fire a round maybe a foot, two feet from his head.

“That would normally be enough to discourage him. But the odd one would continue sniping at our guys and then our marksman would take him out with one shot.”

Through the vicious conflicts, a new term entered the lexicon: ethnic cleansing.

Canadian peacekeepers have been deployed around the world since 1948. Some 175,000 of them have negotiated the delicate balance between policing warring parties and becoming combatants themselves, between the risks associated with respecting their restrictive rules of engagement and violating them; 130 have died.

Places like the Suez Canal, Cyprus, the Golan Heights and Haiti have become synonymous with Canadians in UN blue helmets. But for more than a generation, no place has been linked to Canadian peace operations more than the Balkans.

The ethnically based conflicts that followed the 1991 collapse of communism in Soviet Russia and across eastern Europe shocked the western world out of its post-Cold War triumph with graphic images of concentration camps, emaciated prisoners, violent death and wanton destruction. Through the vicious conflicts, a new term entered the lexicon: ethnic cleansing.

Canadian troops were there for all of it. From the unarmed observer mission that moved in after the first 10-day war in Slovenia in 1991 to the fighting force that joined the NATO-backed invasion of Kosovo in 1999, the Balkans proved a watershed in Canadian military history.

Over the last decade of the 20th century, a series of thankless and widely misunderstood UN and NATO deployments consigned the Canadians to purgatory in the eyes of their uninformed and indifferent citizenry back home. And that, the evidence suggests, was by design.

“There were orders that the remains [of soldiers killed in the Balkans] would only be brought to Montreal as opposed to Trenton, and only during the hours of darkness,” said MacKenzie. “It was a shutdown.

“The casualties were every two or three weeks. There were a lot of limbs lost in minefields. But, no, there was very, very, very little publicity to it. And that was a direct order—God knows from where, but I imagine PCO [Privy Council Office] was issuing instructions to that extent.”

Yet the Balkans ultimately transformed Canada’s soldiers from peacekeepers to peace-enforcers to peacemakers.

They emerged from the wilderness of the 1990s poised to reclaim the mantle of fearsome war-fighters they had earned through two world wars and Korea. The events of Sept. 11, 2001, would propel them down that path and transform them yet again, this time back to that role they once knew so well.

The Afghanistan mission cost them 158 lives, but elevated them in the eyes of Canadians, who rallied behind them in myriad ways, including elevated attendance figures at Remembrance Day ceremonies in Ottawa and elsewhere.

For Canadians now, peacekeeping has largely become a thing of the past. At their 1992 peak, 3,285 Canadian peacekeepers were deployed worldwide, the bulk of them to the Balkans. As of Dec. 31, 2020, just 39 (25 military; 14 police) were scattered across six UN missions. That’s five more than the previous August, when the number of uniformed Canadian personnel on peacekeeping duties was at the lowest since 1956.

The Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was formed after the First World War—one of many questionable cartographic rewrites by the Allied powers that left a legacy of ethnic and territorial tensions which, it came to pass, could only be kept in check by totalitarian regimes of one kind or another.

After the Second World War in Yugoslavia, it was war hero and president Josip Broz Tito who kept the factions in check, declaring that no one under his watch “questioned who is a Serb, who is a Croat, who is a Muslim; we were all one people.”

With his death in 1980, the foundations of the federation began to crack. Ultimately, they splintered and shattered.

Under the leadership of future war criminal Slobodan Milošević, the largest republic, Serbia, rallied Serbs throughout Yugoslavia behind centralized control. The national army soon devolved into a Serbian army as it tried unsuccessfully to maintain the status quo.

Slovenia and Croatia declared independence on June 25, 1991. The short-lived war in Slovenia followed; the Croatian War of Independence would continue until 1995, costing some two million people their homes and 200,000 their lives.

The other republics declared independence. Bosnia was most affected by the fighting. The UN intervened. NATO forces took action against Serbian forces in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia.

MacKenzie made sure they arrived with more firepower than they were authorized to pack.

By the time he landed in Sarajevo in April 1992, MacKenzie was a veteran of eight UN peacekeeping tours in several different mission areas: the Gaza Strip (1963 and 1964), Cyprus (1965, 1971 and 1978), Vietnam, Egypt and Central America, where he had just commanded the UN Observer Mission in 1990-1991.

The 860-member Canadian battle group arrived shortly after. Two-thirds were from the Royal 22nd Regiment (Van Doos) out of Germany. A company from the Royal Canadian Regiment in Petawawa, Ont., joined them. The UN force would total 14,000.

MacKenzie made sure they arrived with more firepower than they were authorized to pack—83 armoured personnel carriers instead of the 13 they were told to bring, along with mortars and wire-guided anti-tank missile systems equipped with night vision. MacKenzie had been told he could bring the missile launchers but not the missiles, and that the mortars could be illuminating-only, not high-explosive. The restrictions, said MacKenzie, were dictated by “stupidity.”

The city had been peaceful, but as soon as the first UN troops arrived, snipers started firing on demonstrators from the roof of the Holiday Inn. MacKenzie had 200 staff officers and a handful of Swedish conscripts at his command.

“You say to yourself, ‘Well, what can I get away with at my court martial?’”

Humanitarian activities seemed the logical choice, so the UN troops started evacuating local hospitals and escorting ambulances “until we discovered that a lot of the ambulances were filled up with ammunition.” One blew up.

UN and domestic officials were concerned that the force was stepping outside its mandate, but MacKenzie said the International Committee of the Red Cross and other humanitarian organizations were leaving Sarajevo in droves.

“Meanwhile, the UN had neither the ability to provide for nor supply our troops up front. They were told to go into hotels in the early days, and there was no money to pay the hotel bills, no money for food, etc.”

The Canadians brought what they needed. Where there were shortages, the various contingents traded among themselves.

MacKenzie became a master at pleading his case to the international media. With his headquarters under almost constant fire, he was ordered to move house to Belgrade—a humiliation, if ever there was one.

“With a name like ‘protection force,’ we had now abandoned the city. We knew what the locals thought of us.”

MacKenzie and his cohorts hatched a plan to “put salve on the wound” by opening the airport at Sarajevo and bringing in food and medicine for the civilian populace.

The Canadians ultimately delivered about 300 tonnes of much-needed relief, and the operation kept MacKenzie in the city until the Canadians were relieved. He said they were “the proudest days of my life, watching the Canadians operate.”

At one point, MacKenzie sought to punch some aid into a Serbian section of Sarajevo. In the process, the RCR reconnaissance platoon was taken hostage. Their drunken Bosnian captors threatened to shoot or burn them to death.

Bosnian authorities refused to intervene until MacKenzie produced a videotape proving that the Canadians were not delivering weapons and ammunition to the Serbs, and threatened to get it aired on BBC “within the hour.” The stalemate was broken; the militia backed off.

The alternative would have been a bloody rescue operation in a volatile neighbourhood surrounded by high-rise buildings. The prospect didn’t faze the Van Doos, however. When MacKenzie returned to headquarters with news that the situation had been resolved, he found the French-Canadian quick-reaction force armed-up and rarin’ for a fight.

“They had everything they needed. All they needed from me was the word ‘go,’” he said. “Here was a bunch of francophones who couldn’t move fast enough to attempt the very dangerous rescue of 50-plus anglophones from the RCR. That was a moment to remember.”

Instead of two sides, there could be more than a dozen—all fighting each other,

It was just after this that MacKenzie received a telegram from National Defence Headquarters in Ottawa directing that all maple syrup consumed on Canadian bases and operations should be sourced from Quebec farmers only.

“A whole bunch of my guys were going to be killed and here was the minister [Marcel Masse] and the only thing on his mind is where the maple syrup is coming from.”

The Balkans marked the first time UN peacekeepers were confronted by factional warfare in such a big way. Instead of two sides, there could be more than a dozen—all fighting each other and, more often than not, targeting UN forces too.

Canadian peacekeepers served in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia and Montenegro, and Macedonia. But the powers in Ottawa went to great lengths to suppress the nature of their work.

The vast majority of Canadians believed their soldiers were boy scouts doing the work of beat cops. Meanwhile, one father received his dead son’s personal effects by mail in a plain brown envelope.

In Croatia in 1993, the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry fought Croatian forces in the Medak Pocket. It was to that point the heaviest combat Canadian forces had faced since the Korean War, yet the troops were ordered not to speak of it. It would be years before Canadians learned the true extent of the fighting. Peacekeeping would never be the same.

Canadian medics evacuate wounded during a UN mission in Croatia. The 1993 deployment was marked by combat in the Medak Pocket, a Serbian enclave where Canadian troops came under heavy fire from Croat forces. [DND/LAC/4113927]

“The fact is, all of those missions that involve factions are unsolvable unless it’s done, I don’t know, by political decision-making, perhaps,” said MacKenzie. “But all you can do, if you’re going to commit a force, is protect people.”

In too many cases, under-manned and/or ill-equipped UN forces have failed, refused or been prevented from doing so.

With the increasingly complex nature of conflict, there has been growing reluctance among traditional contributors to continue committing resources. As a result, peacekeeping has become a money-maker for developing countries.

In Canada’s peacekeeping heyday, nations contributing forces received about US$15 a day per soldier in compensation. Canada simply deducted the funds from its UN contributions. Now the compensation figure exceeds $1,300.

“They’re fed; accommodations are provided; they are looked after for the time they are away in the host country,” says MacKenzie.

As of August 2020, the leading contributor to UN peacekeeping operations was Bangladesh, followed by Ethiopia and Rwanda. Leading peacekeeping states typically collect some $13 million a year in compensation.

Early last year, member states owed the UN nearly $2 billion in peacekeeping funding, and more than a third of that arrears was by the United States. UN secretary-general Antonio Guterres called it a “troubling financial situation.”

In the Balkans, UN operations gave way to NATO forces and a more aggressive strategy, culminating in the 1999 invasion of the former Serbian republic of Kosovo. During a pivotal debate over the move in the House of Commons, members from two different parties got the transition backwards.

“I really almost threw something through my big screen,” said MacKenzie. “I couldn’t believe it. That’s how much knowledge there was in government as to what the hell was going on and what we were doing.”

After he returned from the Balkans in October 1992, MacKenzie was appointed commander of army forces based in Ontario. Members of the Croatian community in Canada and factions in Bosnia verbally attacked him for perceived injustices. After criticizing the UN’s inability to command, control and support its peacekeeping forces, the 35-year veteran and the face of Canadian peacekeeping retired from the military in March 1993.

Advertisement