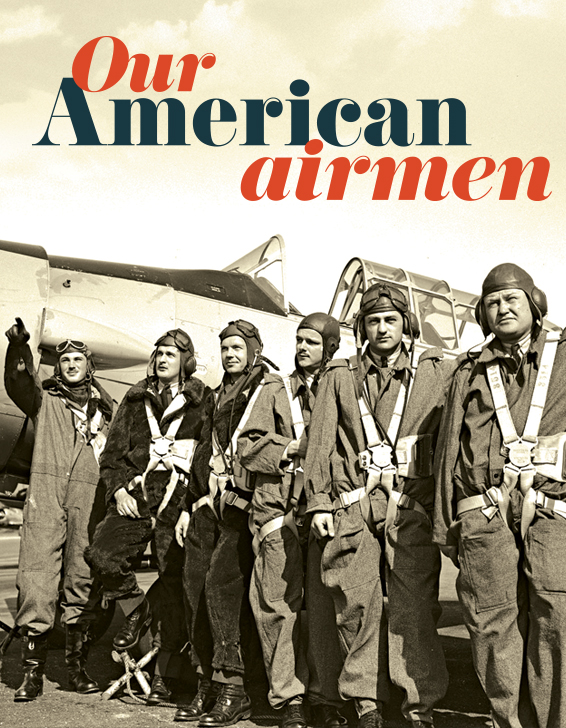

American airmen, all with the rank of leading aircraftman, stand together at RCAF Uplands, near Ottawa, in April 1941. They are identified as (from left) J.G. Magee, A.C. Young, C.F. Gallicher, C.G. Johnston, A.B. Cleaveland and O.N. Leatherman. [DND Archives/PL-2753]

As Canada rushed to find instructors and aircrew for the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, many Americans flocked north.

It was 1941 and Britain and the Allies were losing the war. German Panzers were sweeping across Russia and there seemed to be little to stop them. At home, the United States had not entered the war or even seriously rearmed. Some Americans took note that Canada, not the United States, was the arsenal for democracy. The British Eighth Army was transported on Canadian-made vehicles, and the same army fired Canadian 25-pounder shells from Canadian-made artillery. But the most significant contribution to the Allied victory was not munitions and equipment, it was the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP), which President Franklin Roosevelt acknowledged when he called Canada the “Aerodrome of Democracy.”

Across Canada at 107 schools and 184 support units, the BCATP trained aircrew for many different air forces, but the vast majority were from the British Commonwealth. One “band of brothers” joined the training even though their country was not yet at war. They were the American volunteers who came north to join the Royal Canadian Air Force.

I was eight years old when war was declared and not long after the declaration, my father rejoined his regiment, Britain’s King’s Royal Rifle Corps. He had served in the last months of the First World War and was in reality too old to be an infantry officer, a fact borne out by his being returned to hearth and home in Montreal in late 1940. While he was on duty, my mother, with me in tow, carried on. For myself and my chums, all Depression-era kids, time was spent poring over maps, studying German and British aircraft, and adhering to blackout rules. After all, my father was now an air-raid warden. We joined the Scouts or Cubs and badgered housewives to sacrifice some of their pots and pans and aluminum foil, neatly balled to “throw down Hitler’s throat” for the war effort.

Still the war seemed far away, until one morning our tranquillity was disturbed. The Queen Mary Hospital was turned into the No. 1 Wireless Air Gunnery School. Soon afterward, the first wave of recruits arrived, identified by white markers in their wedge hats, signifying that these were aircrew trainees.

It so happened that our apartment building backed onto the chain-link fence with the barbed wire top which denoted RCAF property. It did not take us kids long to carve out a section of the fence and enjoy the use of the newly built hockey rinks. We also felt it was incumbent for us to teach the Australians, New Zealanders and other less fortunates who lacked a history of snow what hockey was all about.

In fact, the wireless gunnery school had at least 10 nationalities who were training as Bomber Command aircrew. The Aussies in their unsuitable but quite unique winter-blue “passionate purple” uniforms and inimitable accents quickly became a legend as the “wild colonial boys,” a phrase from an Australian song by Banjo Paterson. One story, never refuted, told how the Down-Under crew stole a Montreal streetcar because they were angry at the lousy service.

There was, however, another slightly less rambunctious group, and these were the “Yanks” with their shoulder patch declaring “USA” underneath an eagle rampant. Initially, in contravention of American law, both the Royal Air Force (RAF) and RCAF recruited American instructor pilots and aircraft maintenance personnel to help with the BCATP. At the same time, Americans—some, but not all, with pilot qualifications—were coming to Canada to volunteer for the RCAF. There were a lot of them, at least 8,500, but more than 1,000 came from one state, enough to warrant the expression “Royal Texan Air Force.”

For the British, the Yanks were welcome as aircrew for Bomber Command and as a vehicle to demonstrate to the American public, by every form of media possible, that while Britain would survive, for Germany to be defeated, America had to be in the war. To this end, the

British had launched what historian Nicholas Cull called the most “diverse, extensive…undercover campaign ever directed at a sovereign state by another.” Orchestrated by Canadian-born spymaster William Stephenson, the ultimate aim was to get the U.S. into the war. Who would be better to express that need than American volunteer aircrew, the Eagle Squadron?

One of the many successes was getting Hollywood to recognize the heroism of the Eagles. That led to the classic film Captain of the Clouds with James Cagney (“Airmen on set,” September/October 2017).

There is a scene in the movie when Air Marshal William (Billy) Bishop, playing himself, presents pilot’s wings to a 1941 RCAF graduating class. One of the men is from Texas. “One of our most loyal provinces,” quips Bishop.

So how many Texans did join the RCAF? Best estimates say it was more than 1,000. It was the largest number from any one state. Just behind was New York with about 1,000, followed by California. Many simply crossed the border, found the nearest enlistment centre and signed up. Most came via the Clayton Knight Committee.

Knight was a renowned aviation artist who flew with the British in the First World War, and he had well-placed chums. He joined forces with Bishop, backed by Homer Smith, a Canadian living in the U.S. and heir to a fortune made in the oil industry. Knight activated the Clayton Knight Committee in 1940 with its mission to bring Americans to Canada, particularly instructors for the now operational BCATP. Essentially, it worked as a secret and illegal recruitment company with the blessing of Roosevelt and under the benign eye of J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI. Money was no object, allowing the committee to set up recruiting offices in first-class hotels in every major city.

American airmen jumped at the chance.

Squadron Leader Lance Wade, commanding officer of No. 145 Squadron, in his Spitfire near San Severo, Italy, in November 1943. [Wikimedia]

Recruiting was one thing but there was also the rather annoying problem of the oath of allegiance to King George VI, which all Commonwealth citizens were obliged to take. Like many issues considered intractable, this one was easily solved. The American recruit would swear that he would “agree to obey all RCAF rules and discipline” for the duration of the war, a war many Americans were clamouring to join.

Then, there was the harsh reality of the era: the Spanish Civil War, the Italian invasion of Ethiopia, the Great Depression, the rise of Adolph Hitler, the failure of appeasement and the brutality of Nazi Germany. Americans were listening to Edward R. Murrow’s unforgettable voice reporting on the Blitz from London. All created an ethos of frustration, anger and a growing sense that Hitler had to be stopped.

If the immediate threat of invasion had passed, the only offensive weapon the British and the Allies had to take the war to Germany was Bomber Command. But it would take some time before the bomber offensive could do any real damage. Nevertheless, the key component was in place: the BCATP that would graduate thousands of aircrew, pilots, gunners, navigators, observers, bombardiers, flight engineers, wireless operators and ground crew to service the aircraft. This huge enterprise formed the context for the American volunteers.

“There was something of the First World War’s adventurism and romanticism in flying; an air of exciting improvisation of the whole experience,” claimed Brigadier-General Philip Caine of the United States Air Force. However, as with any collection of people, some of the motives to volunteer were less than noble: broken marriages, failed businesses, boredom, financial debt. Some were trying to escape poverty by riding the rails to find work. Some, like H.A. Clayton, were very well off. Clayton had his own aircraft, was a qualified chiropractor, a first-rate athlete and a licensed pilot.

And who could have believed it when the top RAF ace in the Mediterranean and North Africa theatres would be a muleskinner from the scrub-hill country of east Texas? Lance Wade was his name and he ended up a wing commander. He was a natural fighter pilot with 25 confirmed kills. Tragically, Wade was killed in a plane crash in 1944.

I met some of the Texans who were starting their training at No. 1 Wireless Gunnery School in Montreal. On occasion, my family would agree to provide a much-appreciated home-cooked meal to some cadet whom I would invite to our apartment. Of course, the opening question would be, “How do you like Canada?” It would be followed by, “Why did you want to join the RCAF?” The answer to the first was always diplomatic, “People are generous, but the weather is another story.” The second was more difficult. The flip answers were always, “I needed a job” or, “It sounded like a good idea” or, “I wanted to learn how to fly.”

But there was another factor. Honour, duty, protection of family and loyalty to country meant something. It was two sided. Norman Mailer, author of the Naked and the Dead, served in a Texas unit in the Second World War and noted the Texans’ ferocious behaviour.

Texans have a history of being ruthless in war. Witness the Indian Wars along the frontier, the war with Mexico, the Civil War and the Texas Revolution. On the other hand, history shows that Texans are quick to volunteer to resist tyranny and oppression in the name of honour and individual freedom.

No surprise then that the Texans would volunteer to “stop Hitler.” Their loyalty is best illustrated by Wade, who was awarded the Distinguished Service Order, Distinguished Flying Cross and Bar. When America finally entered the war, Wade was offered a chance to move to an American fighter squadron. But loyalty prevailed, “Thanks, and that is mighty fine,” he said, “but I would rather keep stringing along with the guys I have been with so long now.”

Advertisement