The No. 2 Construction Battalion band was created to help recruit Black volunteers at churches and rallies. [Lt.-Col. D.H. Sutherland Collection, River John, N.S.]

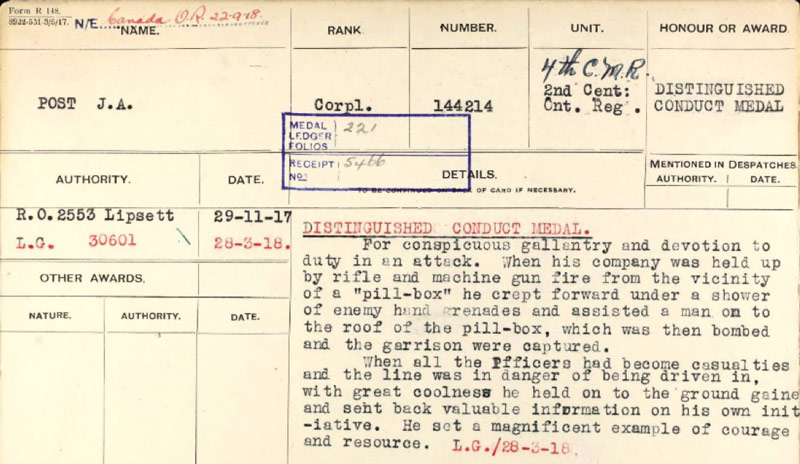

Post, a corporal in the 4th Battalion, Canadian Mounted Rifles, also happened to be one of about 700 Black men who served in non-segregated units of the Canadian Expeditionary Force between 1914 and 1918.

Black volunteers faced daunting obstacles on the road to First World War service.

“When his company was held up by rifle and machine gun fire from the vicinity of a ‘pill-box,’” said his citation, “he crept forward under a shower of enemy hand grenades and assisted a man on to the roof of the pill-box, which was then bombed and the garrison were captured.

“When all the officers had become casualties and the line was in danger of being driven in, with great coolness he held on to the ground gained and sent back valuable information on his own initiative. He set a magnificent example of courage and resource.”

When Canadians think of Black service in the First World War, they most often think of the country’s only segregated unit, No. 2 Construction Battalion.

Blacks faced daunting obstacles on the road to First World War service in the CEF. They were banned by many units before conscription became law in 1917, yet hundreds managed to join non-segregated units. About 160 joined infantry battalions, an undetermined number of whom would have seen action on the front lines in France and elsewhere.

Blacks served as officers and non-commissioned officers. They were killed and wounded in action. They earned medals and plaudits before returning home at war’s end to discrimination and persecution from their widely indifferent compatriots.

Post, who went on to become a sergeant, had three older brothers who all served in non-segregated units: Patrick was a driver with the 25th Battalion (Nova Scotia Rifles); Montague was a lance-corporal in the 1st Canadian Division who returned to action after he was wounded and gassed at the front; drummer Frank made it as far as England before a bad heart forced him back home.

The stories of James Post and many other Blacks who served in the Canadian military during wartime are finally being told thanks to historian Kathy Grant and Scott Moody, an Ontario middle-school principal and a veteran of wars in Afghanistan and the Balkans. He’s been a soldier, mainly a primary reservist, for 30 years.

The pair have researched the stories, collected photographs, engaged youth, spread the word and pooled resources and expertise to create the website Black Canadian Veterans Stories with the help of a 16-year-old army cadet, Hakim Foyn, who reviews content with an eye to language and presentation that is meaningful to youth.

The developing website, made with assistance from Veterans Affairs Canada, is already brimming with stories, pictures and history surrounding Black service in Canada’s military dating from before Confederation through present day. There are even videos.

Army cadet Hakim Foyn, pictured with Lieut. (N) Esrom Tesfamichael, is part of the team on the Black Canadian Veterans Stories website. [Sarah Onyango]

“…be sure and get the Canadian government to honour and recognize the contributions of its Black soldiers.”

The work has been particularly gratifying for Grant, whose Barbadian father was among about 400 Black volunteers who came to Canada from the West Indies to serve in the Canadian Forces during the Second World War.

An army signaller before he transferred to the air force and became a wireless air gunner, Owen Rowe was stationed in Edmonton and stayed on in Montreal after the war.

He beseeched his daughter before he died in 2005 to “be sure and get the Canadian government to honour and recognize the contributions of its Black soldiers.”

Just a month after his death, the Canadian War Museum unveiled a plaque honouring West Indians who fought for Canada in the Second World War.

Grant then turned her efforts to the broader subject of Black service and, boosted by her father’s own files along with those of friends and veterans’ descendants, she has been conducting research, promoting the cause, and lobbying Ottawa ever since.

She also drew on the 1980s work of the late Thamis Gale, who researched more than 1,300 Blacks who served during the Great War. Gale’s Jamaican-born father William was a veteran of the Pictou, N.S.-based No. 2 Construction Battalion.

Charlie Some joined No. 2 Construction Battalion after enlisting in 1917. His death, possibly at the hands of an allied soldier, remains shrouded in mystery. [Anthony Sherwood Productions/Black Canadian Veterans Stories]

She helped create a searchable database of Black soldiers in 2010 and has participated in numerous exhibitions, acknowledgements and other public education projects designed to “mitigate the gap between the experiences of Black soldiers and mainstream Canadian war stories.”

She has collaborated with the Canadian War Museum, VAC, Library and Archives Canada, Citizenship and Immigration Canada and the Defence Department. Her efforts earned her the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Medal in 2012.

Her Facebook page, which caught Moody’s eye and inspired him to reach out to her several years ago, had more than 9,200 followers at this writing and is viewed a half-million times a year.

She says the subject of Black wartime service in Canada has been rife with error, misconception and misunderstanding—even the narrative surrounding No. 2 Construction Battalion.

Manned by Black soldiers from across Canada, the Caribbean and the United States, and commanded by mostly white officers, the battalion built and maintained the roads and railways that transported vital lumber to the front and operated and maintained vital water systems for the camps.

“These men conducted themselves with honour and professionalism in the face of prejudice, hate, and an unwillingness of other Canadians to serve shoulder to shoulder with them against a common enemy,” says a Defence Department release.

The No. 2 Construction Battalion worked with the Canadian Forestry Corps overseas. [Lt.-Col. D.H. Sutherland Collection, River John, N.S.]

“It just did not happen,” she said in an interview with Legion Magazine. “The records don’t reflect that. They weren’t at the front at all.”

Even now, federal databases and documents number those who served in the battalion at 686 when, in fact, Grant says the figure is around 800. The national archive is currently updating its records.

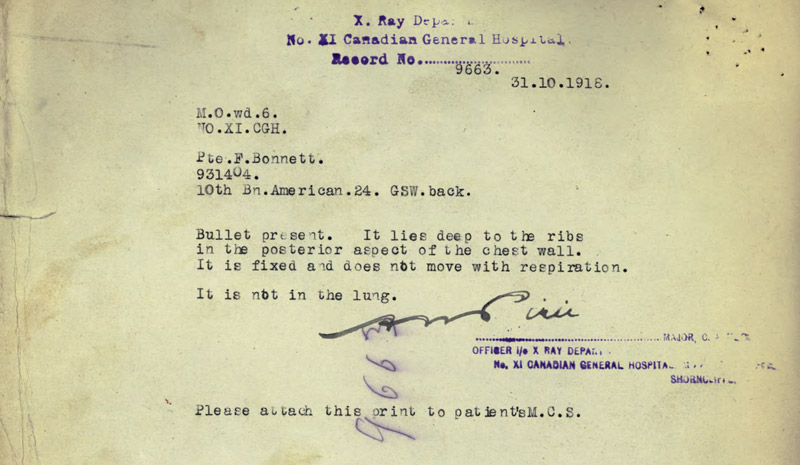

Some members of No. 2 did transfer out to combat units. One, Fred Bonnette—an American-born labourer living in Halifax when he enlisted—made it to the front with the 10th Battalion (Canadian) and was wounded on Sept. 3, 1918.

The bullet lodged between his ribs, the X-ray still in his service record. He recovered, redeployed, and boarded ship for Canada on Jan. 12, 1919.

Challenges, both inside and outside the Forces, continue to this day.

The Government of Canada plans to formally apologize for the way No. 2 soldiers were treated “before, during, and after their service to Canada during the First World War.”

“The members of the battalion, their families, their descendants and their community deserve recognition and acknowledgement from a grateful nation for the sacrifices they made to serve Canada, sacrifices which were not all on a battlefield,” said a DND statement.

Many restrictions on Black service were lifted by the Second World War. There were no segregated units, but Blacks were initially banned from air force and naval service. Challenges, both inside and outside the Forces, continue to this day.

Preserving and understanding history has been fundamental to Moody, who has been speaking to schools and groups during remembrance periods and otherwise for most of his 20-year career as an educator.

Ontario middle-school principal, veteran, historian and co-founder of Black Canadian Veteran Stories, Scott Moody. [Scott Moody]

“I was learning their stories through research, and finding them through research which was enabled, really, by Kathy. A lot of it led me to her Facebook page. It was incredible.”

Moody tapped into Grant’s work as he related the stories of Black, Indigenous, Asian and South Asian veterans of the Canadian military. He started to amass an archive of his own and encouraged students to do their own research on the subject.

Facebook, however, was out of bounds to the kids and Moody became convinced that a website packed with visuals and information would be the best way to reach them.

“Kathy is the go-to person for this information,” he said. “She is the expert, far and wide. She’s got a great network of people who help her, as well. But Kathy knows the families, she knows the truth, she’s done the research, she’s got the photos.”

He proposed to Grant that they team up and build a site where her research, and his, would be more widely available, especially to youth. They assembled a team of experts to help put it together and maintain it.

“There are a lot of inaccuracies out there,” he said. “There are a lot of myths and stories that have perpetuated themselves, some of them very insulting.

“When you look at World War I, particularly the valorous conduct of many Black Canadians who served in regular units and did amazing things, those stories often get overshadowed by 2 Construction Battalion. Sharing those stories is critical.”

Private James Munroe Franklin of Hamilton, Ont., was among the first Black North Americans killed in the First World War. He died near Regina Trench on Oct. 8, 1916. [IWM/Lives of the First World War/7541555]

“It’s celebrating excellence.”

Moody researched the funding process through Veterans Affairs’ commemorative program and the pair put a proposal together. They were awarded VAC monies for the website, which remains a work in progress—and likely always will be.

New information is surfacing all the time. Motivated in part by the country’s role in Afghanistan, Canadians have become more curious about Canada’s military past, the lives and deaths, and the very human stories of those who served from before Confederation through two world wars, Korea, peacekeeping and in Afghanistan.

“Canada has an incredible story here with regard to Black Canadians and their legacy of service,” said Moody. “And I think that’s a story that needed to be shared accurately and widely…so I hope the website is something that does that well.”

Advertisement