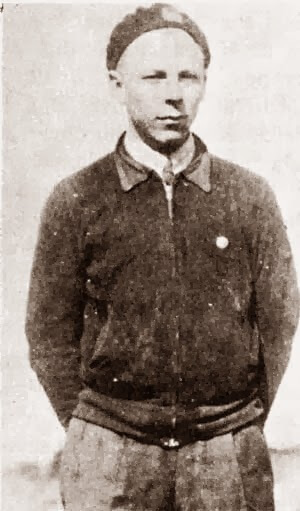

Jules Paivio, the last Canadian veteran of the Spanish Civil War, was granted honourary citizenship by Spain in 2012. [Theberetproject]

Jules Paivio, a 20-year-old Finnish Canadian of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion (the Mac-Paps), watched on as his Italian captors, aligned with the enemy’s Nationalist forces, prepared a firing squad. Together with other prisoners, the 15th International Brigade volunteer pondered his fate.

His birthday was at the end of the month—on April 30, 1938—but he couldn’t imagine living to see it. Such was the brutality of the Spanish Civil War.

A little more than a year had passed since insisting to his father that he would serve the Republican cause. The encounter outside their Ontario home had been etched into his memory, ultimately aided by the poem that the elder Paivio composed. Through stanzas expressing pride, despair and sorrow, his father wrote:

A hard, firm handshake yet

You disappear into the wintry darkness,

I slowly into the cabin stagger

Such contradictory emotions seethe through me

Now depressing me, then again such elation

Pride in a son, who does not fear,

Who wants to fight for right.

That feeling strengthens, inspires me

A son’s loss, a life so young.

Perhaps forever

That presses down on me, in gloom.

Originally from a small Finnish community that would develop into Thunder Bay, Ont., Paivio had long been idealistic. In the early 1930s, he joined Canada’s Young Communist League as a unit secretary and anti-fascist.

When Nationalist rebels attempted to overthrow the democratically elected Spanish Republican government in 1936, Paivio was horrified by the bloodshed depicted across the news reels. He subsequently joined scores of international volunteers, eventually numbering 40,000, despite western non-intervention.

In response, the Canadian government passed the Foreign Enlistment Act on April 10, 1937, barring the country’s would-be volunteers from being recruited. It was a month too late for Paivio, who had already crossed into Spain over the Pyrenees, and did little to prevent those likewise prepared to take the risk.

Approximately 76 per cent of Canadian volunteers, many of whom initially joined the U.S. Abraham Lincoln or George Washington battalions, belonged to either the Communist Party of Canada (CPC) or—like Paivio—the Young Communist League. Meanwhile, almost 80 per cent were immigrants, with a significant number boasting Finnish roots, including more than 100 from northern Ontario.

Canadian volunteers of the Mackenzie–Papineau Battalion in the Spanish Civil War. [Theberetproject]

During an unsuccessful assault on a site called Mosquito Ridge, Paivio found himself trapped in a ravine under intense Nationalist machine-gun fire.

With minimal training—some of which included the ever-inefficient and increasingly obsolete Canadian Ross rifle—Paivio was rushed to the front for the defence of Madrid. Fighting with the Lincolns of the 15th International Brigade, the Finnish Canadian helped counter Nationalist advances.

Paivio next participated in the Battle of Brunete, a Republican offensive to alleviate fascist pressure on the capital and Spanish territories to the north.

“That’s where I really learned about what a war is like,” Paivio once recorded. “The fascist troops, they came out…and had peasants and the townspeople ahead of them…[The Nationalists] were firing at us, and so [Republican-aligned forces] finally had to fire…I can always remember going out of there and marching through with these dead bodies of the civilians…this is war.”

During an unsuccessful assault on a site called Mosquito Ridge, Paivio found himself trapped in a ravine under intense Nationalist machine-gun fire.

“I don’t know how I survived,” he said.

Both the Abraham Lincoln and George Washington battalions sustained horrendous casualties amid the battle, and so, to account for the depleted ranks, the two units merged, and the latter formation was promptly disbanded.

But Paivio’s time with the Lincolns was also drawing to a close. Marching to the rear, the U.S.-Canadian battalion came under attack from Nationalist bombers. “I was holding onto the grass,” he recalled of seeking scant cover.

Paivio joined the newly formed Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion thereafter, its name deriving from the leaders of Canada’s 1837 rebellions. The young volunteer was soon commissioned as an officer and training instructor.

Nevertheless, the respite behind the front was brief as, from March 1938, fascist rebels under General Francisco Franco broke through Republican lines, which virtually collapsed. The period became known as The Retreats, and Paivio, made adjutant of the machine gun company, was swept up with them.

His own personal withdrawal was, however, stopped cold in early April after he was captured. Now, staring down the barrels of a firing squad, the young Mac-Pap, joined by fellow prisoners, awaited his imminent demise.

It was then that a motorcade pulled up near the farmhouse. Stepping out of a limousine, an Italian officer decided to put a halt to the summary execution.

“We were saved,” said Paivio.

But his ordeal was far from over. The Finnish Canadian spent the rest of the war in a fascist concentration camp, finding strength in the fortitude of other internees as he endured disease and brutality until his release a year later.

Though not the last Canadian volunteer of the Spanish Civil War…Paivio was the last combatant.

Franco’s Nationalists ultimately prevailed in the Spanish Civil War. The fascist general reigned in the country as dictator until his death in 1975.

Paivio returned to Canada on May 6, 1939, and, in defiance of the federal government’s mistrust of some 1,600 Mac-Pap volunteers, served as a map-reading instructor during the Second World War. He eventually became an architect and university professor, as well as a veterans’ rights activist.

Jules Paivio died on Sept. 4, 2013—11 years ago—aged 96. Though not the last Canadian volunteer of the Spanish Civil War—a distinction held by 105-year-old William Krehm when he died in 2019—Paivio was the last combatant.

Remarking on his legacy, the Canadian War Museum’s historian Michael Petrou, author of Renegades: Canadians in the Spanish Civil War, said: “Fundamentally, Jules symbolizes a larger group of Canadians who recognized the dangers of fascism before most of the world was ready to do so. For all the complexity and messiness of the Spanish Civil War, he and many others possessed the moral clarity and physical bravery to meet that threat.”

Advertisement