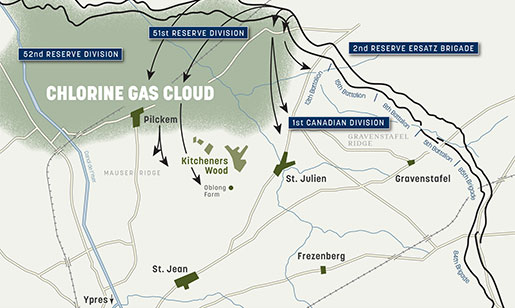

As darkness fell on the night of April 22, 1915, three German divisions, advancing behind clouds of poisonous chlorine gas, had torn a five-kilometre gap in the defences of the Ypres Salient. Two French divisions had been forced into a disorderly retreat, exposing the entire left flank of the Canadian Division.

![A painting by Gordon Wilson depicts the Canadian night attack on Kitcheners Wood. [WATERCOLOUR: GORDON WILSON]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/copp1.jpg)

The historian of the 48th Highlanders of Canada, who was in Ypres that night, described the scene as an “inferno more terrible than Dante’s.” It was, he wrote, “a nightmare, so awful it seems in memory a phantasy of terror and misery. Ypres was under the most terrific bombardment the shell-mauled sector had yet known. Above the old town the sky was a livid void, ablaze from the red glow that rose and fell and rose and fell incessantly. The road to the west was shocked with mad traffic, over-run with terror… It was the river of fear and while it flowed on, dying Ypres, behind, would shake to mighty concessions, would glow suddenly and stand with the fallen walls stained against her own blood-red shroud and the vault of flame over St. Julien.”

Along the Ypres-Poelcappelle road, Canadian soldiers, on their own initiative, tried to prevent a complete collapse, holding on to a series of isolated positions. At the apex of the salient, Montreal’s Black Watch prevented an immediate breakthrough while in St. Julien their commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Frederick Loomis, deployed reserve companies of the 14th and 15th battalions to defend the village.

Major-General Edwin Alderson, the divisional commander, and Brigadier Richard Turner needed to make some immediate, crucial decisions. However, they lacked accurate information about the battle or the enemy’s intentions. No one knew that the German 52nd Div. had been halted on Pilckem Ridge north of Ypres because the 51st Div., in the face of French and Canadian resistance, had failed to keep pace.

This may explain why Alderson agreed to a request from a French liaison officer who sought Canadian support for a counterattack by the 45th Algerian Div. which, he claimed, was preparing to retake the ridge. The idea of immediate counterattacks to regain lost ground before the enemy could consolidate was deeply embedded in military doctrine and it frequently trumped common sense. So despite evidence that the Algerian Div. was in fact incapable of attacking anyone, Alderson ordered Turner to “make a counterattack towards the wood,” continuing to the northwest to link up with the French. Turner, who was under pressure to reinforce the garrison at St. Julien and support the Black Watch, did not question his orders. He committed the 10th Bn., drawn from Brig. Arthur Currie’s 2nd Brigade, and his own 16th Bn. to an improvised midnight attack on Kitcheners Wood.

Kitcheners Wood was set on a slight rise northwest of St. Julien, overlooking the Canadian positions. At dawn a well-hidden enemy could direct observed artillery fire on much of the narrowed salient before launching a renewed attack. The German heavy artillery was in fact moved forward during the night to support a further advance “in the direction of Poperinghe,” well to the west of Ypres.

By chance the 10th Bn. was the first to arrive at the start line. Garnet Hughes, Turner’s brigade major, gave the orders to organize the battalion into lines with the companies 30 yards apart, creating four waves of attackers who were to advance shoulder to shoulder. Lieutenant-Colonel Russell Boyle raised no objection to this formation which had last been used in the War of 1812. He also rejected a suggestion from a more cautious officer that men be detached from the main advance in order to eliminate a suspected German position at Oblong Farm which could be used to direct enfilade fire at the battalion’s flank.

These tactical decisions were compounded when Hughes placed the 16th Bn. directly behind the 10th in the same formation with orders to follow them into Kitcheners Wood. Neither battalion was given specific objectives nor was there any suggestion of how the actions of the two battalions could be coordinated. No one appears to have asked the question of what would happen if the French failed to advance, a situation that would leave the Canadians in trouble. There was no attempt to contact the Algerians by brigade or divisional headquarters.

![Lieutenant-Colonel Frederick Loomis [PHOTO: LEGION MAGAZINE ARCHIVES]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/copp3.jpg)

No artillery support was available until a single 18-pounder gun, under repair in an ordnance workshop, was hitched up and moved forward. With only 60 rounds and no clear idea of where the enemy might be, the gunners fired on the northern edge of Kitcheners Wood.

The 10th Bn., which was to demonstrate extraordinary courage that night, was composed of men recruited by the Calgary Rifles and the Winnipeg Light Infantry, two of Canada’s leading militia regiments. As with other units in the division, their non-commissioned officers (NCOs) and ranks were largely British-born, many with recent military experience. The Canadian-born officers, drawn largely from the two regiments, included several Boer War veterans. Boyle was one of them. Wounded in action, he returned to Alberta in command of a cavalry regiment before he became commanding officer of the 10th Bn. Tall and powerfully built, the 34-year-old tried to shape the battalion in his own image. On arrival in England he challenged anyone who complained about his methods and strict discipline to fight him man to man. No one took up the challenge.

The 16th Bn., known as the Canadian Scottish, was formed from four proud Highland regiments, each with its own regional and clan affiliation; the 50th from Victoria (Gordons), the 79th, Winnipeg (Camerons), the 91st, Hamilton (Argylls) and the 72nd, Vancouver (Seaforths). The Seaforths, who supplied half of the officers and other ranks, dominated and their commanding officer, Lt.-Col Robert Leckie, led the battalion.

![Brigadier Richard Turner, VC [ILLUSTRATION: SHARIF TARABAY]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/copp4.jpg)

Leckie was an obvious choice. A Royal Military College graduate who commanded a squadron of the Canadian Mounted Rifles in the Boer War and been Mentioned-in-Dispatches, Leckie had been singled out as one of the outstanding militia officers in western Canada. He was selected to command 3rd Bde. when Turner was promoted to take over 2nd Div. The regimental history suggests Leckie succeeded in shaping the battalion into more than a collection of rival companies, forging an agreement to wear a common khaki kilt and gradually earning the respect, if not the affection, of the officers and NCOs. The battalion was in reserve behind the Yser Canal when ordered to deploy. An extra emergency ration and two additional bandoliers of small arms ammunition was issued before the 16th moved out.

Leckie had no opportunity to influence the planning of the counterattack. On arrival at brigade headquarters he was told that his task was no longer “to check the German advance” but to “support closely the 10th Bn. and attack the enemy so as to clear the wood northwest of St. Julien.” Leckie was given an extra hour to brief his men when the attack was postponed to 11:30 p.m. They “formed up in the moonlight about 1,000 yards from the enemy… four lines, single rank.” Canon Frederick Scott, the irrepressible padre, appeared shaking hands and murmuring, “A great day for Canada boys! A great day…”

The advance began at 11:45. The 10th Bn. War Diary records that “the only sound was the quiet tramp of feet and “the knock of bayonet sheaths against thighs.” Then a hedge was expectantly encountered and the noise of breaking through brought a hail of bullets. After a “momentary pause” the lead companies raced forward clearing an enemy trench and pressing into the wood.

The 16th Bn. was close behind, but as it passed through the hedge flares illuminated the scene. “We then doubled and when flares went up lay down.” After charging the woods the enemy fled. “Many were bayoneted, others surrendered… men were cautioned about dealing harshly with prisoners.” The Canadians cleared the woods, advanced to the north edge and established a line a few hundred yards forward. More than half the officers and men of the 10th Bn. had fallen, including Boyle. Leckie, as senior officer, tried to co-ordinate the defence of the wood by reorganizing what was left of two battalions that had fragmented into small, often intermingled groups.

Leckie sent messages to Turner, requesting reinforcements and horses to remove the four guns abandoned by a British battery in the initial German advance. There was no response and as dawn approached it became evident that the French attack had been cancelled or failed. The enemy continued to hold Oblong Farm, the northwest corner of the wood and a strong position on the southwest edge. Leckie, after consultations with the surviving officers, ordered a withdrawal to the south side of the wood where they occupied and extended the original German trench, holding on for 24 hours until relieved.

Those who experienced the midnight charge and those who have examined it years later have struggled to make sense of an event that ended with 259 men killed, 406 wounded and 129 missing. The title of Daniel Dancocks’ book on the 10th Battalion, Gallant Canadians, evokes the theme of courage and determination. Andrew Iarocci, who has published the most detailed account of the Canadian actions at Second Ypres, believes that “an immediate counterattack, cloaked by darkness,” was the proper response to the situation whether the French attacked or not. The “principles of active defense,” he writes, “dictated that lost ground must be recaptured as soon as possible. Speed was essential to delay the enemy the opportunity to consolidate.” Iarocci insists that the attack, “although very costly… initially succeeded in driving the German forces from the woods, delaying further German offensive action west of St. Julien. He quotes Leckie’s comment “we gave them an ungodly scare, and checked their advance.” George Cassar’s book, Hell in Flanders Fields, argues that the surprise night attack was an “eminently feasible operation” ruined by “deplorable planning and execution.”

It would be difficult to defend the planning of the attack, but given the haste at which the operation was mounted, the lack of artillery support and the failure of the French army it is impossible for me to criticize the men who executed the attack. The reality is that the British and thus the Canadian Army was ill-prepared for the kind of siege warfare that had emerged on the Western Front. Neither an appropriate doctrine nor the weaponry and logistics were yet available.

Advertisement