Atlantic Patrol was an early success for the National Film Board of Canada. [NFB]

The view looks out over the massive forward guns of a Royal Canadian Navy destroyer. “A never-ending stream of war supplies that Britain must have if victory is to be achieved, manned by men determined that the North Atlantic supply line not be broken,” booms the authoritative voice of Lorne Greene.

It’s the opening scene from a nine-minute film called Atlantic Patrol, released in April 1940 by the newly minted National Film Board of Canada. It was the first in a highly successful monthly series aimed at getting Canadians behind the war effort.

With war clouds looming in 1939, Prime Minister Mackenzie King wanted to unify Canadians; make them “feel Canadian.” He needed more than the CBC and the railways to bond citizens nationally.

Art Director Harry Mayerovitch (left) shows the department’s latest poster to Film Commissioner John Grierson in 1944. [Grierson_John_08/NFB]

He had brought in accomplished Scottish film producer John Grierson to come up with a plan for a Canadian national cinema, asking him to propose something for a new motion picture bureau from scratch. Grierson did that: he founded the National Film Board 80 years ago, in 1939.

It was wartime and Grierson was appointed general manager of the Wartime Information Board. It was a position requiring the talents of both a reporter of current events and a wartime propagandist.

Grierson thought a theatrical series could be used to instil patriotism and keep the Canadian public informed of their country’s participation in the war. He hatched the idea of a monthly film; a new series designed to provide Canadians with a uniquely Canadian view of themselves and to inspire and encourage them to be part of the war effort. The Canada Carries On series was born.

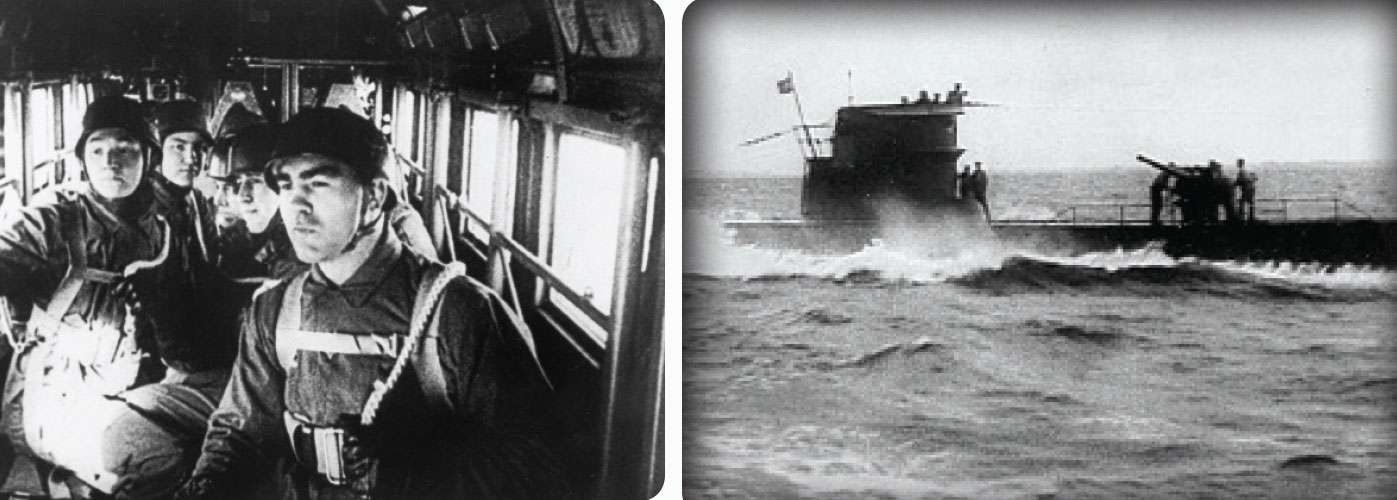

Action scenes in Churchill’s Island, one of the most popular films in the Canada Carries On series, were intended to appeal to a British audience. [NFB/15427_2; NFB/449339]

An authoritarian, Grierson laid down specific and strict criteria for the series. “Firstly, in any given year, six were to be made for Canadian audiences and six for foreign audiences,” says Albert Ohayon, NFB collections curator. “Secondly, there were to be six major themes: get Canadians to focus their collective energies; find purpose in their activities; understand the strategy of war in a Canadian context; respect women for their new wartime roles; unite in a collective purpose to crush tyranny and fascism; and finally, prepare to usher in a new postwar world.” Some of the films did not reference war at all—just feel-good Canadian culture like hockey, maple sugar and the Bluenose.

The theme on women’s roles was notable and clearly ahead of its time. “Grierson was very insistent on that,” says Ohayon. “He said women are going to have a big role in this war and they must be acknowledged.” Titles included Proudly She Marches by Jane Marsh, who worked with Grierson.

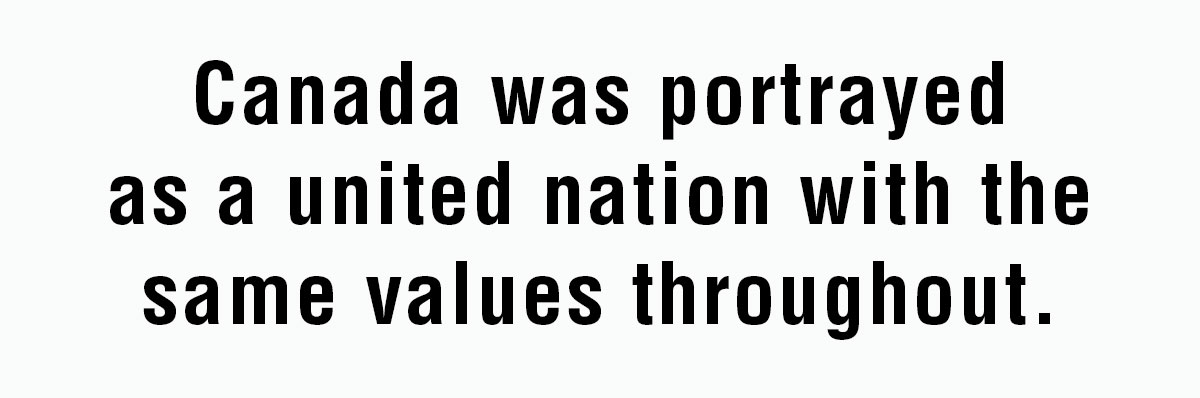

Narrator Lorne Greene would go on to a career in Hollywood. [CBC Still Photo Collection]

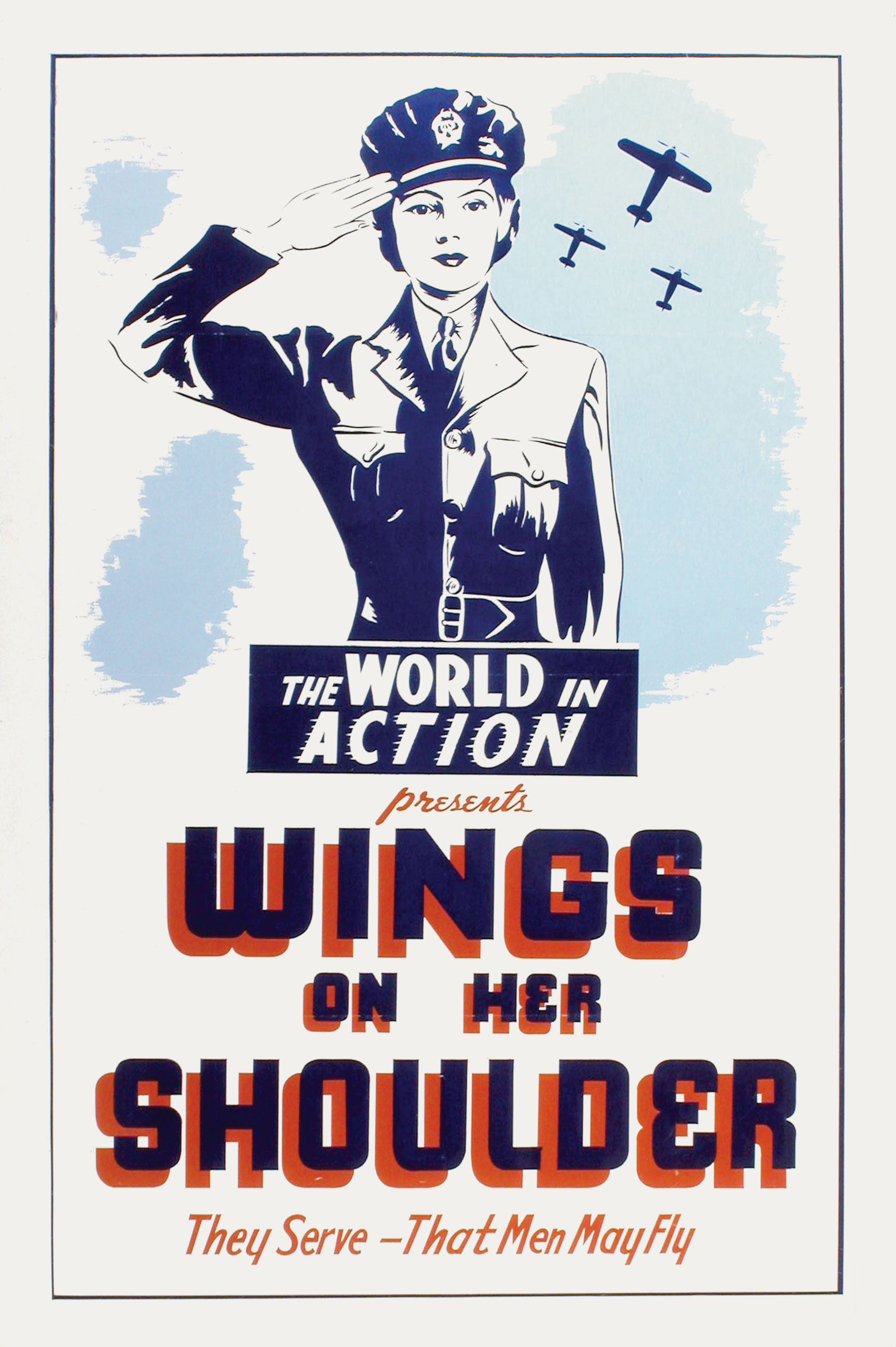

“Marsh was a great filmmaker,” says Ohayon. “She came to the NFB early and directed most of the films on women’s roles in the war.” Included are Wings on her Shoulder and Women are Warriors; and one right after the war called To the Ladies, a tribute.

Footage was obtained from a variety of sources including United States film libraries, Allied forces cameramen and even the enemy. Captured footage was obtained when the Allies intercepted enemy ships and confiscated Nazi propaganda films. Time was of the essence. “A whole outfit in Europe was there to handle and process the films and ship them overnight to Canada by plane,” says Ohayon. “It was a well-oiled machine.”

The series was produced in 35-millimetre prints specifically for cinemas. Each issue was shown in about 800 theatres throughout Canada over a six-month period. Distribution was handled by Columbia Pictures of Canada, and a deal with Famous Players Cinemas of Canada ensured Canadians from coast to coast could see the films.

The role women played in the Royal Canadian Air Force was portrayed in the film Wings on her Shoulder directed by Jane Marsh, one of the few female film directors at the time. [NFB/1121]

A French series was produced as well, under the title En avant Canada, and distributed in Quebec and New Brunswick by France Film Distribution in 60 theatres. Eight to 12 were produced each year—some being versions of the English titles while others were original material.

Those primarily of wider interest were distributed internationally: in Australia, the United Kingdom and the U.S. (by Telenews), in India (by Fox) and the West Indies (by Inter-continental). Among them was Warclouds in the Pacific, released just one week before the Pearl Harbor attack. Presciently, it warned a Japanese attack was imminent. Soon, every American wanted to see it to help understand the Far Eastern threat facing their country.

The most famous and popular film in the series was Churchill’s Island, made for British audiences. “Grierson and [director Stuart] Legg were British and they sometimes released British films as part of the series,” explains Ohayon. “In this case they wanted to give a boost to the British and show that Canada was there to support them.”

Released in Canada in June 1941, it was later launched in the U.S. to great acclaim: winning Canada’s first movie Oscar, and the first in the new category of Best Documentary Short Subject.

Indeed, the films were so successful on the world stage they spawned a new series that would complement them by covering the war with a broader scope. Grierson envisaged a series for domestic and international audiences that would present the global strategy of the war—but from a Canadian perspective. The new set was dubbed The World in Action. Legg was brought over from Canada Carries On to produce the new series and again the voice of Lorne Greene was indispensable.

Grierson would need a distributor in the critical American market. So in early 1942, he went to Hollywood and met with Charlie Chaplin and Mary Pickford of United Artists (UA). He threw in Churchill’s Island. Having won the Oscar, Grierson saw it as a great way to introduce his new series to an American audience. Convinced, UA agreed to distribute the first 12 issues throughout Canada, the U.S. and Great Britain.

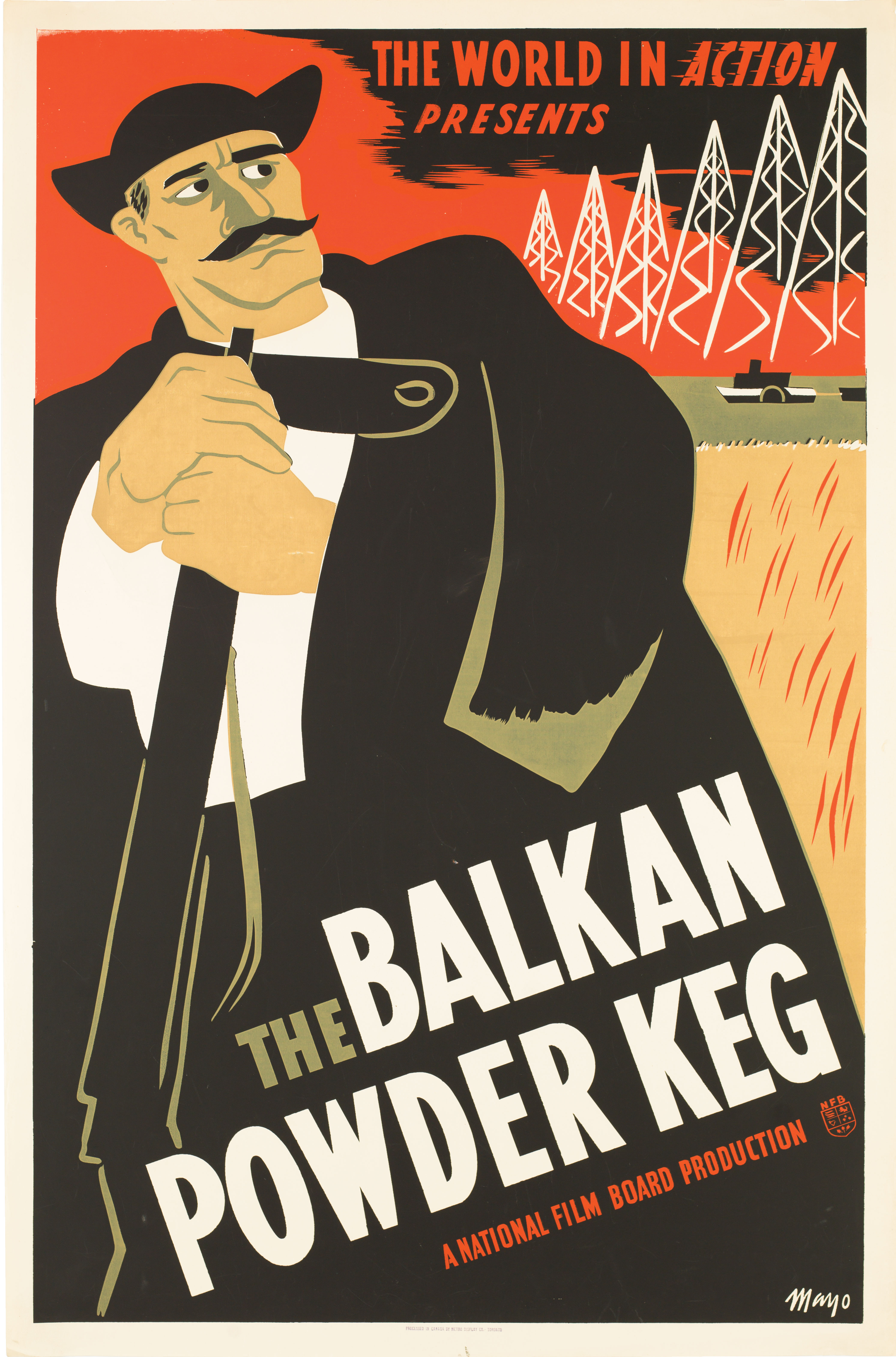

The film The Balkan Powder Keg was pulled from circulation after Winston Churchill complained about its portrayal of British foreign policy. [CWM/19920056-003]

It was not an easy birth. The very first issue, Inside Fighting Russia (a.k.a. Our Russian Ally), a look at the Soviet Union’s fight against the Nazis, ran into a roadblock. UA refused to distribute it in the U.S.—they considered it communist propaganda. Although the U.S. and the Soviets were fighting a common enemy, America’s mistrust of communism was enduring.

After this rocky start, the new series appeared in theatres about once a month to a considerable number of viewers: an estimated 6,000 American and 1,000 British cinemas. In Canada, 23 copies in English were released to theatres and two more in French. Like its sister series, these would circulate for about six months throughout the country.

But controversy still dogged the new series. January 1945’s The Balkan Powder Keg was pulled after just three showings in Canada following complaints from Winston Churchill, who was not amused by what he saw as criticism of British foreign policy in the Balkans. The film was watered down and finally re-released as Spotlight on the Balkans in December 1945 after the war was over.

Because it was wartime, censorship was important, of course. All the films were screened by the Wartime Information Board, which included members of the military.

“Obviously anything that dealt with military secrets was not allowed,” says Ohayon. “There was censorship in regards to heavy casualties such as in the Dieppe Raid. Some films dealt with the raid but it was glossed over rapidly.” Nor was the problem of refugees dealt with, he says. “The government was very much opposed to refugees and wanted to avoid an influx of Jewish refugees so any time atrocities were portrayed it was glossed over too, and Jews were not mentioned by name.”

Canada was portrayed as a united nation with the same values throughout. There is no mention of the French-English differences of opinion toward the war. “Everything shows Canada united working for a common purpose,” he says. “The other thing to remember is that the propaganda in these films is less negative than what the Axis powers were producing. Grierson wanted to avoid denigrating the enemy and painting them as devils.”

Grierson felt that the Nazi propaganda was vicious and negative. He reckoned value was not in putting down the other side; it was all about working together to come up with a better world. “That’s why those original six themes included ‘prepare to usher in a new postwar world,’” says Ohayon. “That was really important; they wanted to make sure to show what was going to happen afterwards.”

Skilled workers were behind the scenes at the National Film Board, including editors. Camera operators and artists worked together to create special effects. [NFB/21690; NFB/11559]

In fact, the films were often sanitized. For example, one shows the Royal Canadian Navy sailing confiscated Japanese fishing boats while patrolling Canada’s western shores. Another puts a positive spin on the forced relocation of Japanese Canadians: “These are not internment camps,” it states.

Production costs were not exorbitant, considering the series’ public impact. The average Canada Carries On film budget had grown to around $15,000 by 1943—about $217,500 in today’s dollars. For the 1944-45 fiscal year, the Wartime Information Board allocated just over $1 million to the NFB—about $16 million today—for producing 44 films of both series and their French counterparts.

Once the films of both series had completed their cinema runs, they continued in the non-theatrical market, playing as part of NFB programs in schools, factories, church halls and service clubs. Copies were made on the more portable 16-millimetre film stock and travelling projectionists, trained by the NFB, ran the films in as many small towns and rural areas as possible from coast to coast. The projectionists, who numbered about 250 by war’s end, supplied their own projectors and, in some cases, portable generators.

Unlike Canada Carries On, which continued production well after the war ended, The World in Action wrapped up in 1945. UA stopped distributing the films in the American market, leaving the NFB little choice but to end production. Some 30 titles were produced in all, over a three-year period. One of the last films in the series, Now the Peace (released in May 1945), focused on the creation of the United Nations and its role in helping shape the postwar world.

The final wartime instalment of Canada Carries On was Headline Hunters, an account of the journalists and broadcasters reporting on the war from Europe and the Pacific. But peace didn’t end the popular series: Canada Carries On continued after the war with a fresh outlook. Topics shifted to Canadian contributions in science, welfare, industry, crafts, music and art. After 199 issues, the series bowed out in 1959. Television had taken over and the voice of Lorne Greene was booming across the ranges of Ben Cartwright’s Ponderosa Ranch in Bonanza.

Advertisement