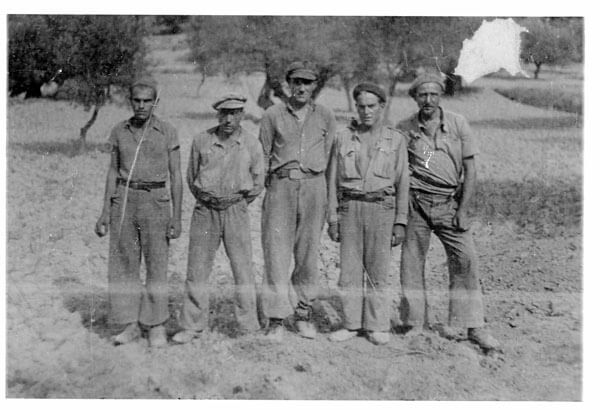

Members of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion in the Spanish Civil War (1936–39).

[Friends and Veterans of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion ]

The Canadian formation—part of the 15th International Brigade fighting fascism amid Spain’s civil war—was powerless to stop the carnage. On that unforgiving summer day in 1938, Higgins and his comrades could do little but stare as buildings, streets and people perished in the bombardment.

Finally, during an apparent window of respite, Higgins and his Spanish comrade José entered the town to see if any civilians could be saved.

The window, however, closed fast. As the duo assessed the damage, a lone Nationalist aircraft scored a direct hit on the local reservoir. A relentless wall of water followed in its wake, sweeping away everything in its path.

It was then that José spotted a young boy, no older than 12 years old, drowning in the torrent. Higgins immediately jumped in and dragged him out.

The child, though still breathing through a fit of coughs and splutters, was severely wounded. Neither Higgins nor José expected him to survive, yet the Canadian machine-gunner cradled him until the bombardment ceased.

“Soy Canadiense,” Higgins repeated in the little Spanish he knew, an attempt to reassure the boy as blood seeped through his shirt: “I am Canadian.”

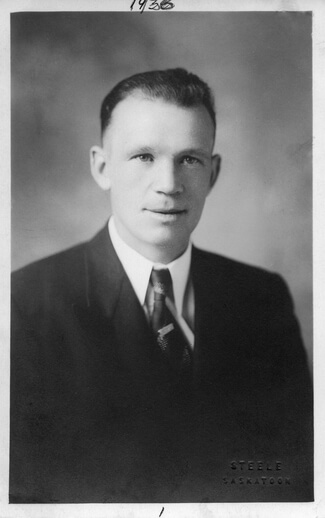

Jim Higgins survived the war and settled in Peterborough, Ont. [Canadians and the Spanish Civil War]

Prime Minister Juan Negrín had seemingly simple objectives: Smash through the enemy lines, push to the Mediterranean Sea and reunite the divided Republic zones with the fervent hope of garnering international attention.

Should western democracies take note, Negrín reasoned, perhaps Spain’s plight would be recognized as part of a much broader effort to confront fascism. Possibly, it could also buy time for a favourable peace agreement.

The prime minister’s optimism poorly concealed his hubris, not least because most European eyes were drawn to Hitler’s designs on Czechoslovakia. Additionally, several logistical questions, not least surrounding supply lines for a large-scale assault across a major river, had effectively gone unanswered.

Nevertheless, in the early hours of July 25, 1938—86 years ago—the newly-formed, 80,000-strong Army of the Ebro, including the Mac-Paps and other units of the International Brigades, launched its ill-fated offensive.

Already, the men had crossed the Ebro in small boats or over lightweight pontoon bridges, launching themselves into Nationalist territory along a vast front. Already, they had taken the enemy by surprise, seizing thousands of prisoners and several objectives—Corbera d’Ebre among them—en route to Gandesa. Already, with 800 square kilometres wrested from the fascists, all without adequate air, artillery or armour support (vehicle-supporting bridges came after the initial assault), Republican casualties were also high.

Things only got worse once the Mac-Paps arrived at the Gandesa stronghold. There, the entire offensive foundered as resistance stiffened.

Republican tanks, having since entered the battlefield, became excellent targets for the Germans’ Nationalist-aligned Condo Legion and their new 88mm artillery pieces. Enemy machine-gun fire, spitting death and destruction across a sun-scorched hellscape, left the Canadians scrambling for negligible shelter. Littering the nearby hills, meanwhile, were unburied corpses left bloated, rotting and animal-picked in the summer heat. The stench was appalling.

The Army of the Ebro went on the defensive from early August as the Nationalists launched repeated counterattacks. By the 15th, the Mac-Paps had taken up barren hilltop positions in the Serra de Pàndols. Unable to dig through the bone-dry earth atop Hill 609, the soldiers relied on sandbags filled with rocks and pebbles; they offered scant protection under enemy bombardments.

For 11 harrowing days, Canadian volunteers—along with the U.S. Lincoln Battalion and the Cuban 24th Battalion on the flanks—repelled wave after wave of Nationalist incursions at close quarters. Some of the Mac-Pap fighters crept around without shoes and slept without blankets. Almost all had no water.

The battered and bloodied Canadians, thrust into the fray a final time at Sierra de Cavalls, departed with only 35 fit and able men.

A short-lived period in reserve preceded news on Sept. 3, 1938—exactly one year before the outbreak of the Second World War—that fascist forces had achieved new gains through the Republican lines. The Mac-Paps were sent into battle the next day—specifically near the Serra de Cavalls—despite their depleted numbers no longer constituting an effective fighting unit.

But the end was in sight for all foreign volunteers. On Sept. 21, Prime Minister Negrín announced the withdrawal of the International Brigades, hoping that the fascists’ German and Italian allies would likewise leave Spain. He was wrong.

The battered and bloodied Canadians, thrust into the fray a final time at Sierra de Cavalls, departed with only 35 fit and able men. It wouldn’t be long until their Spanish comrades joined them; indeed, on Nov. 16, the last remnants of the Army of the Ebro retreated behind their namesake river.

The namesake battle, rather than a fight to ensure an ultimate Republican victory, was instead, in many respects, a struggle to stave off defeat.

It failed. What followed were further months of bloodshed and, after the Republicans were crushed, 36 years of authoritarian rule under dictator Francisco Franco. Only in 1975 was Spanish democracy restored.

Jim Higgins, who had cradled a half-drowned boy in Corbera d’Ebre, survived the Spanish Civil War. So, too, did the wounded child. In 1956, a then-adult Manuel Alvarez immigrated to Canada in search of the soldier who had saved his life. He found him in Peterborough, Ont., in 1978—reunited at last.

Advertisement