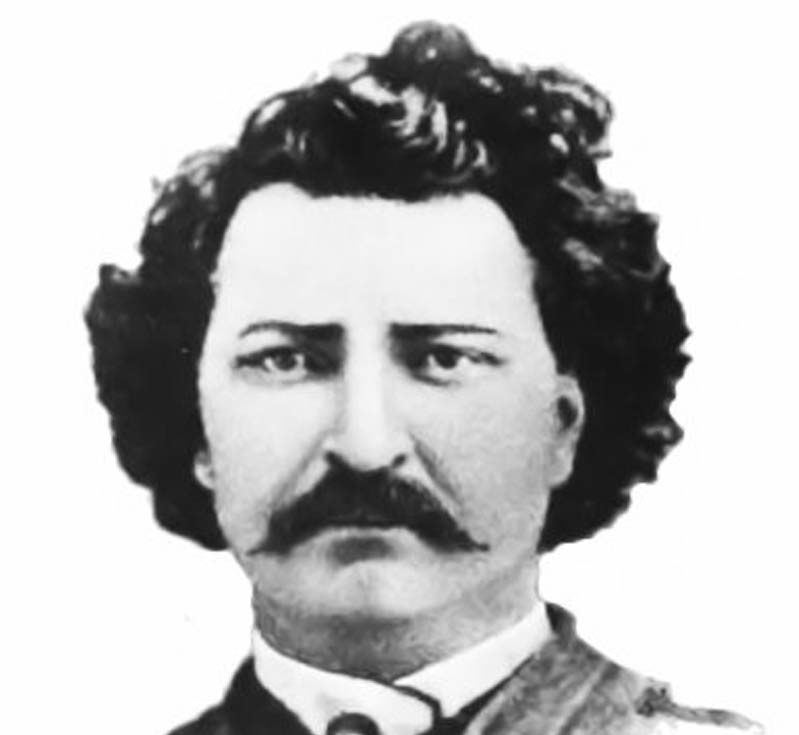

Louis Riel in 1873.[Wikipedia]

“I fear this poor child does not have a good head on his shoulders.”

This “poor child” was none other than Louis Riel, the Métis-born father of Manitoba and protector of Indigenous-French rights in the Prairies. Riel was instrumental in leading two Métis governments and bringing Manitoba into Confederation.

Once labelled a rebel without a cause, Riel’s caricature in Canadian textbooks has changed since the time of his execution in 1885. Today he’s known as a Métis martyr and symbol for French-Canadian nationalism.

“As a proud Métis, I am inspired by this great Canadian hero [Riel], this man of vision and consensus building,” said MP Dan Vandal of Manitoba in a video commemorating the 135th anniversary of Riel’s death, effectively known as Louis Riel Day, on Nov. 16, 2020. “This day is part of Canada’s heritage. It is part of my heritage.” (Manitoba celebrates Louis Riel Day on the third Monday of February.)

Riel was born on Oct. 22, 1844, in the Red River Settlement in St. Boniface, Man., a booming community made up of a cultural hodgepodge of European farmers, fur traders and Métis. Political activism ran in Riel’s family, with his father, Louis Riel Sr. playing businessman, political leader and de facto spokesman for more than 6,000 Métis.

Signs of Riel Sr.’s natural flair for leadership were evident in his son by age 13 when Riel was selected as a candidate for priesthood. Whisked away from his childhood home, he attended a Sulpician school in Montreal where he found himself at the top of the class.

Despite being extremely self-conscious of his Indigenous background, his knowledge of pemmican and tomahawks made him something of an “exotic treat” for teachers and students.

But Riel admitted in a letter back home that the news of his father’s death plunged him “into the depths of pain.” He wrote: “I was advised not to write immediately… so as… not to sadden you too much…. But I cannot contain myself any longer. We must cry, now and forever.”

An introvert and prone to moodiness, his father’s death would turn Riel’s temperament against the Catholic church—or more accurately, the church against his temperament. In 1866, after missing classes and getting in trouble, teachers recommended he leave school. He did so and attempted a career in law. His engagement to Marie-Julie Guernon was called off after her parents discovered his Métis roots and Riel returned to Red River.

“The Métis were resentful. They saw the future of the area being decided without them.”

Back in Red River, Riel discovered that his childhood home had become the eye of a sociopolitical storm.

In March 1869, Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory were being sold by the Hudson’s Bay Company. HBC agreed to sell it to the Dominion of Canada. William McDougall was named lieutenant-governor of the area and surveyors were sent to Red River.

But seeing so many outsiders worried the Métis—and rightfully so.

Many of the Métis were settlers without formal titles who feared that the government would sweep their land, along with their language and religion, away from them.

“The Métis were resentful. They saw the future of the area being decided without them,” wrote the Métis Nation of Ontario in an essay titled “Who Is Louis Riel?”

Not going down without a fight, the Métis community founded the Métis National Committee to protect their status in Red River, placing Riel at its head. In the fall of 1869, Riel and the committee blocked the surveyors and McDougall himself from entering the settlement.

On Nov. 2, 1869, the same day that McDougall confronted a Métis-built roadblock, the committee stormed Upper Fort Gary and seized the site from the HBC to formally establish their own government, despite only having the support of the local French-Catholic population.

“This act was significant for two reasons,” according to the Métis Nation of Ontario essay. “One—it was the first act of resistance to the transfer of the settlement to Canada and two, it established Louis Riel as a champion of the Métis and Métis rights.”

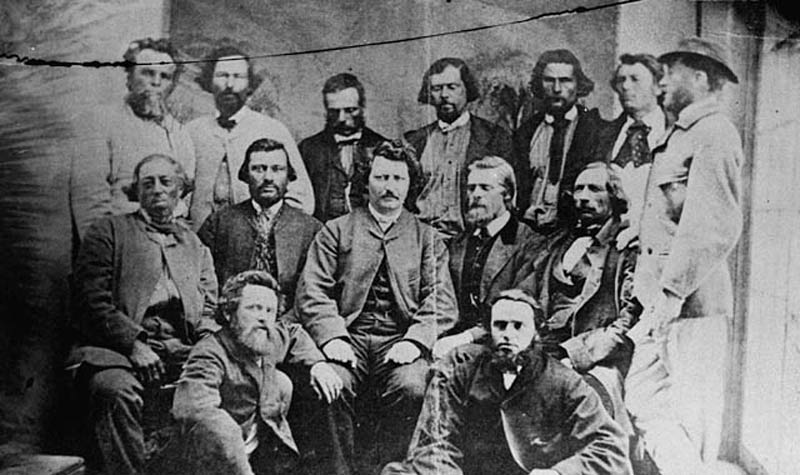

About a month later, the committee evolved into a provisional government, replacing the Council of Assiniboia, with Riel as its leader.

The Métis spotted a Canadian force gathering. Without hesitation, they fell into action, imprisoning them at Upper Fort Garry.

Riel’s provisional government subsequently rejected Canadian authority over Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory, while McDougall refused to negotiate a settlement with the provisional government.

In response, local leaders including Riel proposed a convention in the hopes of uniting with Canada. By Jan. 26, 1870, delegates had drafted a “List of Rights” to ensure the protection of the region’s peoples, particularly its most vulnerable. Riel’s group soon declared itself the Provisional Government of Assiniboia.

It then sent three delegates to Ottawa to discuss the possibility of Assiniboia—or Red River and its surrounding areas—joining Confederation. The governmental bodies would finally reach a consensus by way of the Manitoba Act, merging the ideologies of Parliament with the Assiniboia Provisional Government’s “List of Rights” to create Manitoba. With this, the province was given bilingual status along with 566,000 hectares to allocate to the descendants of Métis residents.

The Métis provisional government.[Wikipedia]

Scott was executed on March 4, 1870. Riel went from “freedom fighter” to “murderer” in the eyes of many. And when a $5,000 award was offered for his arrest, Riel went into hiding. He subsequently suffered a mental collapse and was briefly hospitalized in Beauport, Que.

Upon being discharged, Riel fled to the U.S., spending time in the Midwest and eventually marrying a Métis woman, Marguerite Monet Bellehumeur, in 1882. But Riel’s hope of staying on Montana’s Sun River was short-lived. After the Canadian government began to wane on its promise to respect Métis-owned land in Saskatchewan in the mid-1880s, he was compelled to return to Canada to renew his fight for Métis rights.

“The dream he had cherished for so long was coming true: his people needed him,” wrote the MNO.

Riel returned to support the Batoche Métis, and assisted in creating a 10-point “Revolutionary Bill of Rights,” declaring the freedoms the local Métis had over their own farms. Upon seizing a parish church in Batoche, Riel would once again find himself the head of a provisional government.

Demanding that Fort Carlton be given to the Métis, a two-month battle ensued, and while the Métis put up a strong fight, the Canadian militia eventually overcame them.

Riel was charged with treason and after a fiery trial he was found guilty. On Nov. 16, 1885, Riel was executed in Regina; he would spend his final hours writing a letter to his mother.

Louis Riel statue at the Manitoba Legislative Building grounds in Winnipeg. [Wikipedia]

“Activist. Leader. Nation-building,” said MP Carolyn Bennett in the anniversary video. “Louis Riel helped to shape the country we now know as Canada. And his voice continues to inspire the Métis Nation and all Canadians.”

Advertisement