Privates G. Antosh and D.G. Ripley of the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders enjoy a jar of pickles in 1945. [Captain Ken Bell/DND/LAC/PA-137465]

The Second World War put 750,000 Canadians into khaki uniforms. Men from all parts of the country suddenly found themselves living in barracks and learning how to be soldiers. The transition was not easy and everyone had to learn to march, shoot and fight. The tens of thousands who saw action had to adjust to violence and death. Here is a brief look at what our fighting men wore, ate and said:

[Captain Laurie A. Audrain/DND/LAC/PA-211474]

What they wore and carried

First, they put away their civvy clothes. Just as in 1914, there were too few uniforms for the first units readying to go overseas. Boots were in short supply and some units had only Great War uniforms on hand. But beginning in late 1939, soldiers began to wear a Canadian-produced, higher quality version of the British-designed battledress uniform. Soon all soldiers had it. The blouse, made of wool serge, was a waist-length garment with two breast pockets and a collar buttoned at the neck. The matching trousers had belt loops, buttons for braces and pockets to hold maps and a field dressing.

Equipped to sustain themselves for two days, Canadian soldiers land on Juno Beach in June 1944. [Lieutenant Ken Bell/DND/LAC/PA-132655]

Well-pressed, with rank, unit and formation badges on display, the uniform could be quite smart looking. Worn with the new field service cap at a jaunty angle, Canadian soldiers looked good. Senior officers in tailored battledress looked better still; some even opted for softer Barathea cloth.

Although the battledress was of good quality, it was hot in summer and not warm enough in cold weather. In action, the uniforms absorbed dirt and mud and became sodden in wet weather. They might be covered with a greatcoat or parka in winter, occasionally even with leather jerkins, sheepskin jackets or white ski pants and jacket.

In operations, new clothing might be issued by a Mobile Bath and Laundry Unit if an MBLU managed to get forward far enough to let soldiers—sweaty, dirty and sometimes infested with lice—get clean. Major Stewart Bull of the Essex Scottish Regiment recalled an MBLU getting to his unit in Normandy “and there, oh blessed ‘there,’ was an overhead shower…. We had lots of soap and we got a clean feeling. Some of us [got] some clean clothes—clean underwear and socks, and got them on…that was a bonus for the day.”

From 1943 on, men in the field wore a beret, khaki for most, black for armoured units and maroon for airborne. In action, soldiers wore a steel helmet with a chinstrap and camouflage net. The heavy, uncomfortable helmet provided no protection to the back of the neck (except from rain) and bounced while running.

Soldiers in training wore khaki or denim coveralls, which were also worn by armoured units and those working with vehicles and machinery. Summer dress ordinarily consisted of a khaki shirt and shorts. In winter in the field, Canadians dressed for warmth, many acquiring leather jerkins or sheepskin jackets.

Tin water containers with cork stoppers were issued by the Royal Canadian Navy. [CWM/19750011-043]

Every man had the 1937 Pattern Web Equipment, designed to be maintained with regular applications of Blanco cleaning compound. Attached to the belt or straps over the shoulders were a variety of pouches for ammunition, a small pack for necessities, a respirator case (often left behind as soldiers came to realize gas was unlikely to be employed against them), utility pouches for extra ammunition, a bayonet hanger and an entrenching tool carrier. Officers had a binoculars case, a compass case and a pistol holster. The soldiers’ large pack, designed to be carried on the back but usually left behind with the unit transport, held sleeping gear, blankets, the greatcoat and other equipment considered unnecessary in action.

In battle, soldiers adapted their equipment to what worked best. Each carried a heavy load of some 20 kilograms. A private had a Lee-Enfield No. 4 Mk I .303 rifle and one or two bandoliers holding 50 rounds each. He usually carried one or two 30-round magazines for his platoon’s three or four Bren light machine guns, at least two No. 36 or No. 69 hand grenades, and likely 2-pound bombs for the 2-inch mortar or 3-pound projectiles for the company anti-tank weapon. A water bottle hung on his web belt along with his bayonet; many also carried a knife. On the back was the absolutely indispensable spade or pick needed for digging in.

Snipers with the Régiment de la Chaudière wear British winter camouflage clothing in the Netherlands in January 1945. [Lieutenant Barney J. Gloster/DND/LAC/PA-137987]

Bren gunners had to lug the gun, weighing some 10 kilograms, and wireless operators carried the bulky radio with its telltale aerial sticking up high. Most non-commissioned officers had Sten submachine guns; officers had a Sten and a revolver. In Italy, Tommy guns (Thompson submachine guns) were used.

In the soldier’s small pack was a groundsheet, a few tins of food saved from ration packs, hard tack for emergencies, cigarettes and a lighter, an extra pair of socks, a sewing kit (called a ‘housewife’), extra eyeglasses, shoe polish, shoelaces, a shaving kit and a toothbrush, a condom or two in case unexpected opportunities arose, aluminum mess tins, a mug, a folding knife, spoon and fork, mail from home, a few photos, a deck of playing cards and a pay book.

Manufactured by the British T.G. Co. Ltd. in 1940, this marching compass (right) was issued to certain Canadian soldiers. [CWM/20050130-001]

That anyone could walk, let alone run, under this load was a testament to the soldiers’ fitness.

What they said and sang

Canadian soldiers had to master the army’s strange language. There were military abbreviations, such as RSM (Regimental Sergeant Major), CQMS (Company Quartermaster-Sergeant), CO (Commanding Officer), CSM (Company Sergeant Major) and Adj (Adjutant)—these were the officers and NCOs (non-commissioned officers) who controlled daily life.

There were slang terms like ‘Aldershit,’ used to describe the Aldershot training camp in England. Italians were ‘Eyties,’ Germans were ‘Jerries,’ and there was also a ‘Jerry can’ for carrying petrol or water (sometimes in the same uncleaned can). Soldiers hoped they might be ‘LOB’ when their unit had to attack. A man left out of battle was supposed to be part of the nucleus around which a decimated unit could be reconstituted. ‘Snafu’ was Situation Normal: All Fucked [or Fouled] Up, ‘recce’ was reconnaissance, ‘meathead’ was a provost or military policeman, ‘Zombie’ was a home-defence conscript, and ‘ring knocker’ was a Royal Military College graduate who used his contacts to get ahead.

Canadian comedians Johnny Wayne and Frank Shuster were among the entertainers who performed in stage shows for the troops. [Wikimedia]

The usual expletives were in constant use, so much so that in Sicily in August 1943, the padre of the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada actually tried to shame the troops into cleaning up their language by including one particularly shocking swear word in the title of his sermon to a compulsory church parade. A letter home noted that this resulted in “a few nervous titters” but no lasting effect: “Most of the men lace their talk with cuss words as naturally as they take air into their lungs, and perhaps inoffensively.”

On parade, soldiers marched to military music. Some units had smuggled instruments overseas when bands were forbidden, then unveiled them in England when it became safe to do so. Highland regiments had their pipers, of course, and at Dieppe and on D-Day some units were piped ashore. But mostly soldiers in barracks listened to Benny Goodman’s or Glenn Miller’s big bands on the radio or quietly wept when Vera Lynn sang “The White Cliffs of Dover” or fantasized to “Lili Marlene,” which was unique in being popular with both the Allies and the Germans. Sometimes the sense of being on a forgotten front produced ironic soldier-written lyrics like “We are the D-Day Dodgers in sunny Italy.”

There were also stage shows, produced by the army and featuring Canadian performers. Comedians Wayne and Shuster, for example, made their careers by performing in Canada, Britain and behind the front in Northwest Europe as part of “The Army Show,” a lavish musical and comedy revue that was extremely successful.

What they ate

The army fed the troops well, but there was no pretence of fine dining. Most Canadian soldiers, growing up in the Depression, had never experienced good food and army grub likely suited most just fine.

If rations could not be brought forward in the field by the company cooks, soldiers lived on the Composite Ration Pack, a crate with enough food for 14 men for 24 hours. Put together in Britain, ‘compo’ rations included hard biscuits, waxy margarine, tins of meat and vegetables, cheese, tea, jam and hard candies. One of the most sought-after cans was that of a sweet molasses-soaked pudding. There were also matches, seven cigarettes for each man, canned heat, and six sheets of toilet paper per soldier. The rations weren’t very good, one soldier recalled, “but we managed and we kept alive.”

Members of the 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade (left) eat from mess tins aboard a landing craft en route to France on D-Day. [Lieutenant Ken Bell/DND/LAC/PA-190144]

On the other hand, a good company cook could feed his soldiers well. Cooks scrounged for food, supplementing issued rations. The CQMS had the food carried forward in ‘dixies’ (large iron cooking pots) that kept the contents hot. The men ordinarily received a diet heavy on bread, potatoes, beans and meat that aimed to provide at least 3,000 calories a day. Of course, wrote one gunner with more than a hint of bitterness about his service: “Our quartermasters had it rough with…the first grab at the rations.”

Soldiers always “ate when they could,” a sergeant in the Cameron Highlanders remembered. “If you had an opportunity to have a hot meal, you did…but to sit down and…have a leisurely meal, no, you never did. You could be having breakfast when all of a sudden hell would break loose and Jerry shells you, so that was the end of your breakfast.”

Individual soldiers also foraged, liberating what food (and other valuables) they could from civilian homes and farms. One officer wrote from Germany that he had seen a dispatch rider with a dozen chickens fastened to the back of his motorcycle and “two soldiers pushing & pulling a pig & another sharpening a knife on a grindstone. Don’t blame them a bit either.”

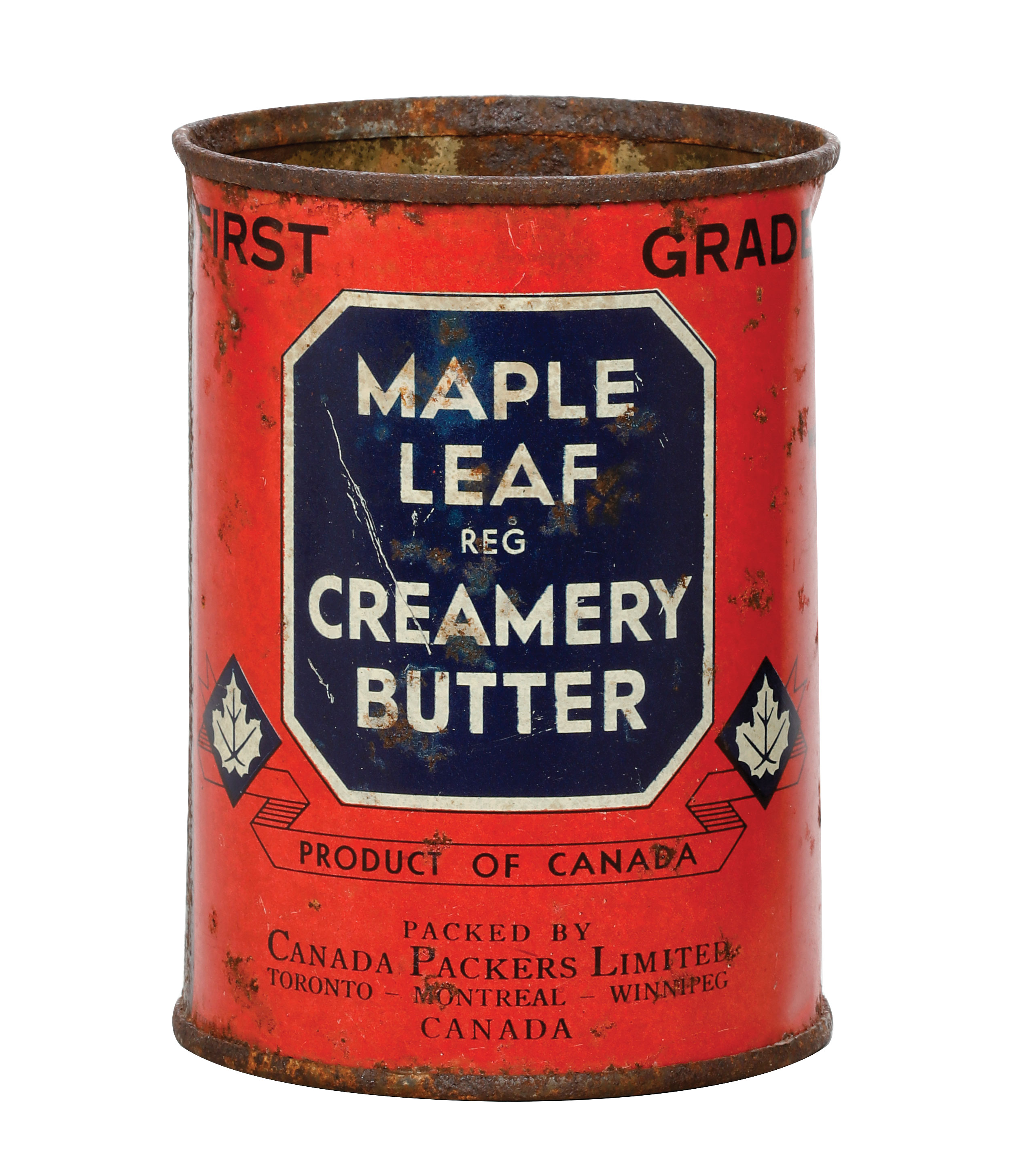

A Second World War-era tin of Maple Leaf butter. [CWM/19980036-001]

Officers could eat well out of action, although at the front they ate the same food their men received. The North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment’s Hal MacDonald wrote on July 22, 1944, that his “batman-gunner is frying meat patties—bully beef, onions, potatoes and crumbled hard tack. They look and smell very good.”

A unit’s officers’ mess, if well back from the front, had better food, the extras paid for by its members’ ‘extra messing’ funds, and there might even be the occasional mess dinner.

Parcels from home were prized. Private Geoff Turpin of the Royal Montreal Regiment wrote from Normandy that “Your parcel was most appreciated, as you can imagine. It was the composite one…, including chocolate from Cunninghams, chocolate bars…& life savers…. McBride (my hole mate) & I melt the chocolate & dip army biscuits in the result. Chocolate biscuits! It also makes good hot chocolate.”

But Turpin still needed some things from home: “Cigarettes are the problem at the moment, because we can only buy 60 English ones a week. Very cheap at 20 francs for 60. But I still love my Winchesters.”

Patriotic Canadian charities raised money to send cigarettes overseas, and family members could buy and mail 300 cigarettes for $1. Cigarettes functioned as hard currency in the Netherlands and in occupied Germany, where a carton could buy almost anything from jewelry to Leica cameras to sex.

Sergeant C. Orton of the Highland Light Infantry of Canada takes a swig of cider in France two weeks after D-Day. [Lieutenant Ken Bell/DND/LAC/PA-133113]

Sometimes, the army showed real initiative. In Arnhem, Netherlands, in the winter of 1944-45, when it seemed the war might never end, a smart staff officer on General Guy Simonds’ II Canadian Corps headquarters set up ‘The Blue Diamond,’ an army-run eating spot. “The bakery will turn out 2,000 rolls, 100 pies and 4,000 doughnuts daily,” the officer wrote, and “the butcher will mince enough meat for 2,000 hamburgers daily, 700 pounds of onions are being used weekly.” In fact, the hugely successful café served 6,000 burgers a day in its first month of operation.

Then there was water. The civilian water supply often had been destroyed and there was the rational fear of poisoned reservoirs. In the field, rivers and streams too often were full of dead humans and animals. Purification tablets made water foul-tasting. The only truly potable supply of water came from the Army Service Corps’ tanker trucks, although it invariably tasted of chlorine.

Sterilizing water with tablets was a two-step, 30-minute process. [CWM/19850419-022]

Soldiers received occasional issues of beer, but never enough, and they always searched for beer, wine and liquor, liberating bottles from enemy caches or from farms and homes. This they drank straight from the bottle, sharing it with their mates. A few delicate souls could not bring themselves to swig from the bottle, and at least one soldier remembered that he carefully tucked a heavy glass tumbler into his pack, wrapping it in his extra socks, so he could drink with some propriety.

At war’s end, Canada’s soldiers became civilians once more. Did they eat better than in the army? Most did. Did they swear less? Perhaps. Did they forget their time in the army? Some tried but few succeeded. The certainty is that wartime service marked everyone who survived.

Advertisement