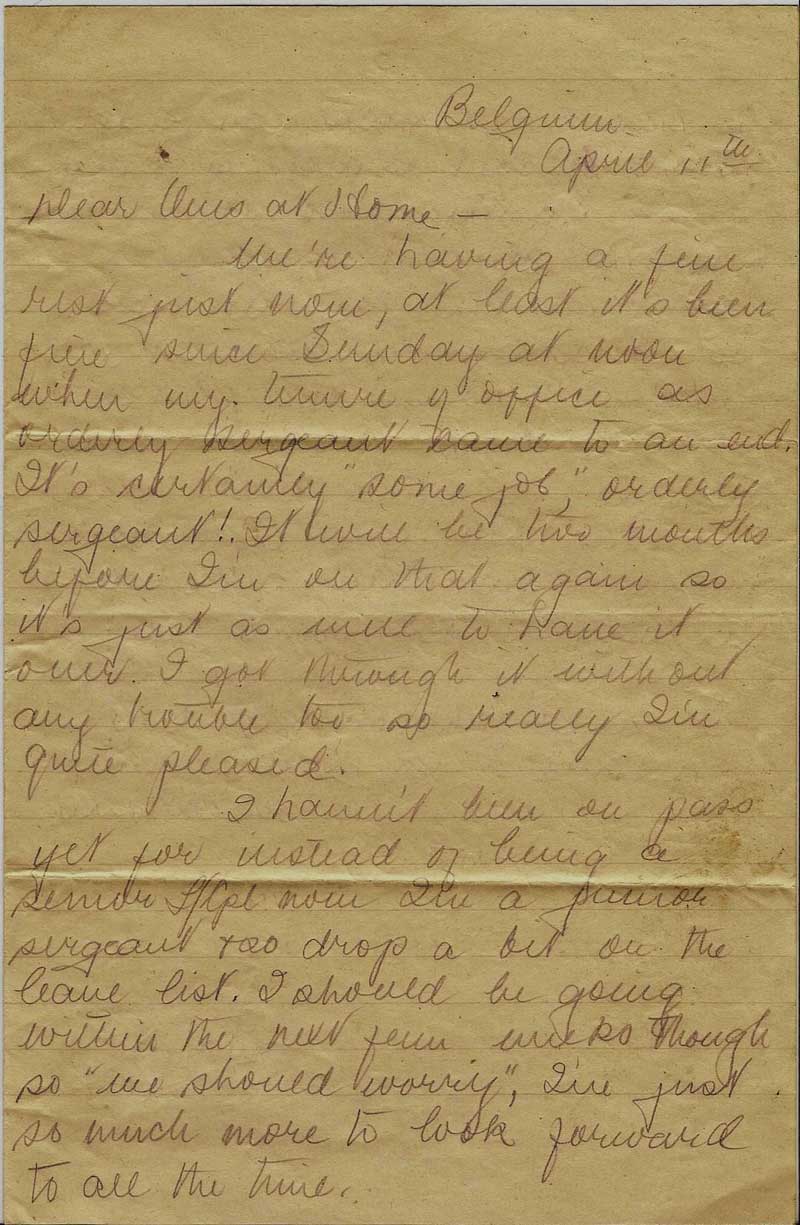

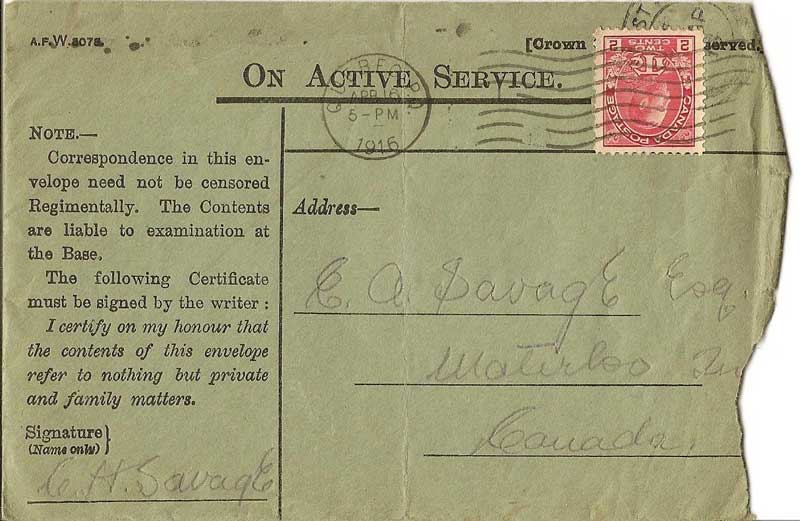

Charles Henry Savage, 1914. [www.canadianletters.ca]

Our first trip in the trenches was a short one for instructional purposes…Although late in October, there had not been a great deal of rain and the front line and communication trenches were in almost perfect condition when compared with those we took over after the rains had begun.

Trenches in this sector were very difficult indeed. The water was so close to the surface that the “trench” really consisted of a built up fortification. To build up a trench of that sort you must have sand in bags, and to get sand into bags requires much labour with a shovel. We only called it sand because it went into sand bags. Actually it was the stickiest of clay in most places.

As the rains came on, these built-up trenches were constantly collapsing and having to be rebuilt. The communication trenches became in most places not only useless but positively dangerous. There were always tales going round of men being drowned in the mud and water of these trenches, although I never heard of an actual case. The Messines front in the winter of 1915-16 was literally a mud hole.

As we approached the line we saw for the first time in most of our lives the effects of shell fire. Not that the Ploegsteert country was badly shot up, far from that, for civilians carried on in some cases right up to the ends of the communication trenches. But there were houses that had been struck by shells, and abandoned chateaux that had been pretty well wrecked.

Charles Henry Savage. [www.canadianletters.ca]

[W]e were able to make our first trip late one afternoon. Probably the Germans had noticed the unusual movement of troops in the communication trenches for shortly after we arrived they put on a mild “straff.” We all stuck up our heads to see what was happening and then and there got our first lesson in trench-craft. Our hosts advised us to keep our heads down or we would get them “damned well blown off.” We did so in some embarrassment and were then told that the shelling was due to the unnecessary amount of commotion that we had made coming into the trenches. Having thus quickly and efficiently reduced us to the condition of humility most suitable for beginners who would learn, they then proceeded to teach us. Each man was detailed to work with some men or group of the other battalion and a similar arrangement was made for the NCOs.

The shelling during this trip was only very casual but later in the war harrying ration parties became a regular science.

As a lance-corporal, I was first of all sent out with a ration party. There was nothing particularly exciting about this, although some of my most harrowing experiences later in the war were with such parties. The rations were the responsibility of the Quartermaster. This officer remained at the battalion horse-lines during the day and at night brought the rations by horse transport to some place, as near the line as possible where they could be turned over to the various ration parties. The roads up to the line were well shelled on and off during the night and likely spots for ration dumps were given special attention by the German artillery. Neither transport nor ration parties had any desire to linger, and a ration dump was one place behind the line where everyone was perfectly willing to hurry.

The shelling during this trip was only very casual but later in the war harrying ration parties became a regular science. One very efficient procedure that the Germans developed was often followed when they had located a dump. If six guns were being used, two would be loaded with shrapnel, two with high explosive and two with gas; then all six would fire at the same time on the ration dump. This might be repeated five or six times during the night at irregular intervals, and could be most annoying.

A listening post detail generally consisted of six men and a corporal or lance-corporal. Two men were stationed either in a hole or at some protected spot in No Man’s Land beyond our wire, two more were on duty at the place inside the trenches nearest the listening post, and two more would be resting.

Duty started as soon as it became dusk and lasted until “stand to” just before dawn. Generally a sequence of two hours on post, two hours in the trench and two hours resting would be followed, but this depended largely on the weather: in the summer the same men might stay out four hours, while in the winter it was often necessary to change every hour.

I smacked every rat that mistook me for a bag of rations. I got some rest, but needless to say, no sleep.

Generally the post in No Man’s Land was connected with the men on duty in the trench by a wire or cord and messages were sent back and forth by a prearranged code. The signals our section generally used were: one pull from inside the trench meant “Are you all right?” and a single pull in reply meant “Yes;” two pulls from inside, “Someone is coming out to your post from our trench,” two pulls from outside, “Send up a flare,” which of course meant that they had heard some suspicious noise. Three or more pulls from outside was a call for help. Any other messages had to be taken out by the corporal, who, as a matter of act, spent a good deal of his time at the post or going back and forth between the trench and the post.

My first visit to a listening post may have been exciting to me, but it was quite apparently just part of the night’s work for my instructor. We pulled ourselves up over the parapet and he walked calmly off into the dark and towards the German trenches. How I admired his nonchalance, and how close I stuck to him! Just outside our wire we were challenged in a low voice and the corporal gave the password, which was, if I remember correctly, “mounted.” I was never quite sure whether this password was given in honour of our first trip into the line or because they thought that even such greenhorns as we would be able to remember that word. After we had been on the post, which was a hole in the ground, for a few minutes, the corporal knelt down in the hole and lit a cigarette, half of which he allowed me to smoke. Even such a novice as I recognized this as a wide departure from “standard practice.”

After we came in from the listening post I was told that I might turn in for a while if I could find a place. This was not easy as the trench was, of course, crowded. I finally decided to try the broken-down dugout where we had stored our rations earlier in the night. The night had already lasted about forty-eight hours and a few hours sleep would go very well. I had failed however to take into consideration two very important factors, namely, the cheese in our rations and the rats in the trenches. When I came, the rats left, but as soon as I lay down they appeared again and swarmed over me on their way to the cheese. I wrapped myself, head and all, in a thick blanket, leaving only my right arm out. Then taking an entrenching tool handle I smacked every rat that mistook me for a bag of rations. I got some rest, but needless to say, no sleep.

The next time Savage and his comrades saw a trench up close, it was all business.

My company was first stationed in support trenches in the vicinity of what was then known as Stink Farm, not at all an unusual name for an abandoned farm close to the line. Since I had had listening post instruction, I was sent up to the front trenches with my section to do a listening post for A Squadron.

Once you got used to the idea of being in No Man’s Land, a Listening Post was probably as safe, or safer, than any other place in or near the front line. Of course, there was the chance of being bombed by a German patrol or hit by a stray bullet, but the chances of being hit by a shell, rifle grenade, or trench mortar in the front line were much greater. As a matter of fact, No Man’s Land as such scarcely existed on the Canadian front; generally speaking we controlled it right up to the German wire. There were, however, certain circumstances that could complicate this work and we got a taste of them on this our first trial.

The battalion on our right had decided to pull off one of those trench raids that were becoming so popular late in 1915. Due to a bend in the trenches the part of the German line that they were to raid was immediately in front of our listening post.

For some reason or other the raid was not successful and was broken up at the German wire. For the next hour the members of the raiding party were crawling back to their own line across our front and through my listening post. Under such circumstances it was always an open question whether the noise one heard was being made by a friend trying to get back to our line or by a German patrol with offensive designs. Ordinarily two pulls on the signal wire would have been answered by a flare and a chance to see what was happening but under the circumstances a flare was out of the question and we had to rely on a low challenge.

The moment after challenging was always a ticklish one, for you never knew whether the answer would be the password or a bomb. Much the same sort of situation, only to a lesser extent, occurred whenever one of your own or a neighbouring battalion’s patrols was known to be out between the lines. Eventually listening posts were generally abandoned in our Brigade in favour of offensive or scouting patrols.

The day after the raid the Germans retaliated on us with shell fire and trench mortars, and as there were no deep dugouts it was quite impossible to get any sleep during the day. We had never seen a trench mortar before and when the first one came through the air like a clumsy coal-oil can and landed in the bay next to us, we were all curious to know what it was. We soon found out! I doubt if anything is more terrifying than the explosion of a large trench mortar shell. Later at Ypres we were to have plenty of practice in dodging both trench mortars and rifle grenades but they were comparatively rare.During the second night one of my section was killed while on post outside the trench. I was standing beside the signal wire in the trench when it gave a sudden jerk and then began to go back and forth rapidly. I got out to the post as quickly as I could and found that one of the men had been shot through the head and killed instantly.

The boy who was with him didn’t say anything and I didn’t pay any particular attention to him. I went in and got one of the other men to help me bring K—- in, but when we lifted him out of the hole there was so much blood flowing that my helper became violently sick and had to go back to the trench. This was the first casualty that he had seen. Eventually we started in with the body. The path through the wire to a listening post was narrow and deliberately crooked, and to carry a heavy man with full equipment and a dragging great coat along it in the dark was almost impossible. It must have taken us a good half hour to get him to the parapet of the trench.

As we approached there was some unnecessarily loud talk in the trench. I crawled up on the parapet and sticking my head over told whoever it was to keep his mouth shut. That was a great mistake, for the talker happened to be the only senior officer in the Regiment without a sense of humour. He told me to come into the trench, and when I waited until a flare which was up had gone out, he gave me a terrific bawling out. He never forgave me for what he considered a piece of insubordination.

When I took another man out for listening post, we found that the man who had been there with K—- was out of his head. He was only a boy, about fifteen years old, and apparently was quite unfit for this sort of thing. After we got him into the trench he became quite violent and I was lying beside him trying to quiet him when he suddenly stopped breathing.I didn’t know what had happened, but after about half a minute I gave him a slap on the side of the head and said “Breathe!” Each time I did this he would breathe and if I didn’t do it he wouldn’t breathe. The medical sergeant didn’t know what to do, but we got hold of a third year medical student who was temporarily camouflaged as a sniper, and he did the trick. He looked over the Medical Sergeant’s supplies and said “I’ll give him a hell of a shot of this, probably it’ll kill him.” But it didn’t. K—- was the first man killed in my company and the second in the Regiment. I have seen hundreds of men killed and dead bodies lying so thick in places that it was almost impossible not to step on them, but this single casualty is the one that stands out most clearly in my memory after twenty years.

After a few days away taking anti-gas training, Savage returns to the trenches, which have changed much.

The line to which I returned from the gas school had gone from bad to decidedly worse. Not only were the communication trenches impassible, but in many places the front line was nearly as bad. Practically all communication had to be across the open; parts of the front line were always collapsing, and of course casualties mounted.

It was impossible to keep our feet dry, and the combination of wet and cold often brought on a condition known as “trench feet.” Apparently there were only two remedies, or preventatives, for this: dry socks and boots, which was practically impossible, or whale oil. This whale oil was supposed to be rubbed on the feet once every twenty-four hours, two or three men at a time being allowed to take off their shoes for this purpose. Ordinarily no one was allowed to have his shoes off at any time in the front line or in the close supports, so it was no unusual thing to go ten or twelve days without having one’s shoes off. Eventually it was made a crime to have “trench feet” and quite a serious punishment was imposed on those who allowed their feet to get into that condition. This I am sure had far more effect than the whale oil, which in spite of all orders was used almost exclusively as a fuel.

Except for cooked meat, which was sent up to us, unwrapped, in sand bags, we did all our own cooking when in the front line during the winter of 1915-16. Of course, a fire without smoke was highly desirable and a wick floating in a tin of whale oil provided this. The hot food was good for the circulation, so the whale oil indirectly fulfilled its intended mission.

In the line we used to eat whenever there was time, and we had anything left to eat. Each man carried a cigarette tin of bacon grease, begged from the cook in billets, and everything that could be was cooked or re-heated in bacon fat. Bread, or hard-tack fried in bacon fat, with a mess tin of scalding tea to go with it, was delicious at any time and particularly so after two or three hours on listening post. The friend who had such a feed waiting for you when you came off post was a friend indeed. Another favourite dish was oatmeal cooked with condensed milk and water. Tea was the regular drink but parcels from home often provided us with Oxo and occasionally coffee. Parcels were always shared out with the section and were one of the brightest spots in our lives. Decorations should have been handed out to the steady parcel senders.

This front was really very quiet and when we came out of the line shortly before Christmas we had had surprisingly few casualties. Both Germans and Canadians were so busy fighting the common enemy mud, that they had very little time to devote to each other.

Charles Savage’s complete memoir can be read here.

Advertisement