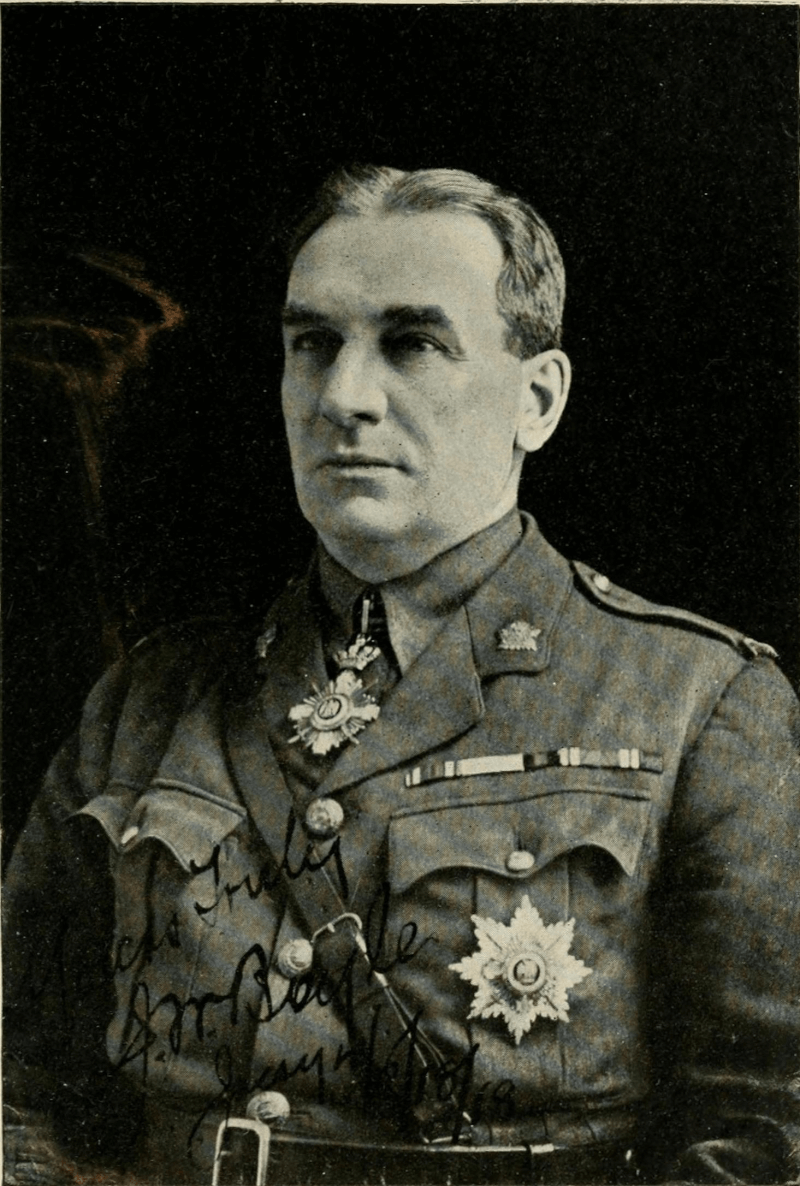

Klondike Joe Boyle used some of his gold fortune to assemble Boyle’s Mounted Machine Gun Detachment, later to become the Yukon Motor Machine Gun Battery.

[Wikimedia]

By times sailor, prizefighter, sourdough, spy and royal confidant, the son of Irish immigrants was among the first to employ large-scale mining techniques in the gold fields of Canada’s Yukon Territory.

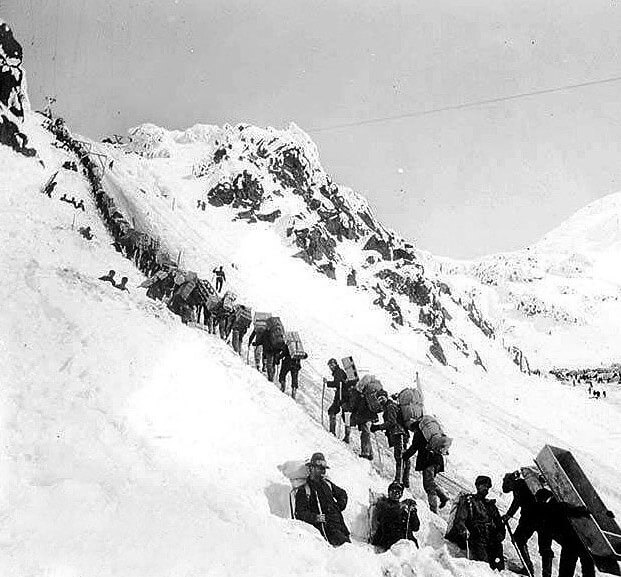

No friends to the environment, Boyle and others swept in on the heels of the Klondike Gold Rush, replacing prospectors’ sluices and pans with enormous electric-powered dredges, taking millions of ounces of gold from the creeks and waterways while wreaking devastation on the virgin landscape.

But the enterprise made him a rich man and, after he was rejected as a 46-year-old war volunteer in 1914, he used some of that wealth to buy weapons, outfit a platoon of Yukon miners, and form what was originally dubbed Boyle’s Mounted Machine Gun Detachment, later to become the Yukon Motor Machine Gun Battery.

Prospectors and others carry supplies up the Chilkoot Pass during the Klondike Gold rush of 1898.

[George G. Cantwell/Washington University Library]

All were privately financed by wealthy Canadians, none of them quite so colourful and intrepid as the larger-than-life Klondike Joe.

Not one to do things half-baked, Boyle gave his new fighting recruits badges, rumoured at the time to be made of Yukon gold: crossed machine guns with a crown, a “Canada” scroll, and a medallion with “Y.T.” and what appears to be an embossed gold nugget beneath.

The Dawson Daily News declared the new unit “the pride of the Yukon,” describing its Boyle-outfitted “natty new uniforms comprising khaki trousers and woolen shirts to match, yellow mackinaws, and stiff-brimmed sombreros”—Stetsons, in fact, like those worn by their mentors, the North-West Mounted Police.

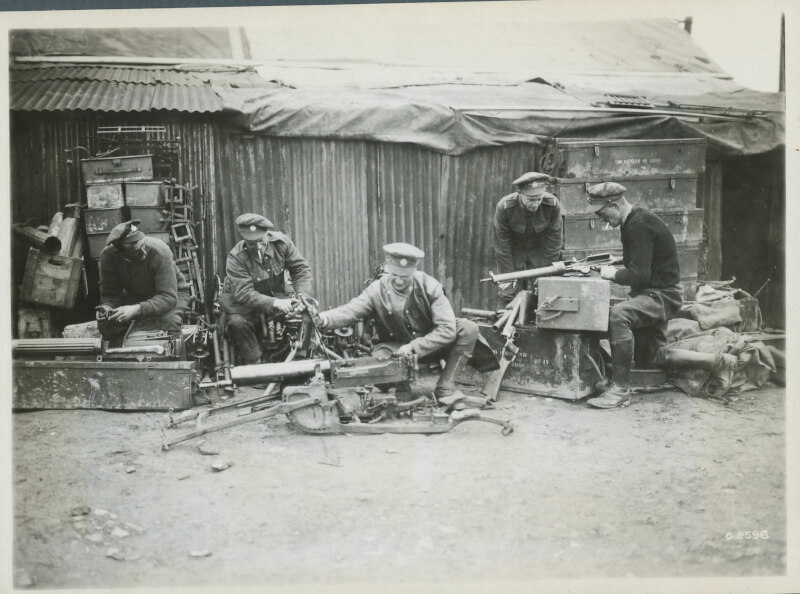

Due to production problems, the Canadian-made Colt machine gun (left) was hard to acquire while the British were reluctant to compromise their own supply of the more reliable Vickers (right).

[CWM]

Attempts by Boyle and others to acquire the industry-leading Vickers machine gun from the British, however, were rejected. Instead, units were to be issued the inferior, Canadian-made Colt, which was lighter, but more complicated and less reliable. It wasn’t a well-liked weapon and, regardless, acquiring it proved difficult.

The first of the motorized units, the Automobile Machine Gun Brigade No. 1, shipped out with the first Canadian contingent in October 1914. It was commanded by French immigrant Raymond Brutinel and financed via the well-connected Clifford Sifton, Wilfrid Laurier’s former interior minister. It was made up of eight open, lightly armoured trucks, each with two mounted weapons.

Boyle’s 46-man unit was the second one formed. It received initial training from the police detachment in Dawson City and the local rifle association before making its way by paddlewheel steamer and transport vessel to Vancouver for more traditional military training.

But morale problems set in during the winter of 1914-15. The men were gung-ho as they signed their attestation papers and were formally sworn in as members of the Canadian Expeditionary Force in the month following their arrival.

An armoured car from the Canadian Motor Machine Gun Brigade carried a crew of five and two Vickers machine guns.

[CWM/19930013-846]

They received 60 horses—52 mounts for the men and eight to be fitted with pack saddles for the machine guns. Boyle visited the unit in January 1915, and ordered them “Mexican stock saddles,” Colt revolvers, nickeled spurs and Hudson’s Bay blankets.

The cowboy-style saddle was the same used by the North-West Mounted Police of the era.

“Very likely, Boyle would have been inclined to emulate them, NWMP Superintendent J.D. Moodie having helped with the formation of the unit,” Cameron Pulsifer, former research chief at the Canadian War Museum, wrote in a paper published by The Northern Review, a journal of Yukon College in Whitehorse.

“This most likely would have been the case with the type of Colt revolvers that the unit received as well, the New Service Colt being then the standard sidearm of the NWMP. The Hudson’s Bay blankets, presumably for use as saddle blankets, would have been a unique touch.”

The badge worn by Boyle’s Yukon Machine Gun Detachment after the unit was re-designated the Yukon Motor Machine Gun Battery upon entry to France in 1916.

Finally, an exasperated group of Yukoners—the “Boyle Battery”— were temporarily incorporated into the 2nd Canadian Mounted Rifles Regiment in April 1915.

The third of Hughes’ motorized machine-gun units, a gift from a wealthy Montreal business tycoon, left Montreal for England on May 17, 1915, without vehicles or machine guns. Due to the mud and stagnant trench warfare that was developing on the Western Front, the British War Office had informed Ottawa it no longer wanted armoured car units. And Colt was having production snags.

A fourth machine-gun unit, financed by department store magnate John C. Eaton, was authorized on Dec. 31 and, like its predecessor, shipped out in early June with neither vehicles nor machine guns.

Finally, after Boyle wrote several letters of complaint to the militia and defence minister, Sam Hughes, an exasperated group of Yukoners—the “Boyle Battery”— were temporarily incorporated into the 2nd Canadian Mounted Rifles Regiment (2 CMR) in April and they all made for England on July 1, 1915.

The Boyles had to shed their distinctive uniform in favour of 2 CMR’s approved Canadian khaki tunic, khaki breeches, lace-up boots with knee-high puttees and Stetson hats. Still lacking their own, they were equipped with 2 CMR weapons.

Furthermore, military leaders were finding themselves saddled with more mounted units than suited the radically changing environment of the new industrialized war; as a result, 2 CMR and the Boyles alike were forced to give up their horses.

Members of the Canadian Motor Machine Gun Brigade clean and repair an assortment of weapons: Vickers Mk 1 (left); a captured Maxim MG-08 (centre); and a Lewis Mk 2 aircraft machine gun. Machine-gun crews were equipped with cleaning kits, tool kits, and spare parts wallets for each weapon they were issued. Crews were responsible for minor repairs to worn or broken parts and daily cleaning of the gun. The average lifespan of a water-cooled barrel in a Vickers machine-gun was between 15,000 and 20,000 rounds.

[CWM/19930013-847]

“Instead of re-donning the uniforms provided for them by Boyle, however, much to their distress, and at the insistence of the commanding officer at Shorncliffe, the Yukoners were attired in the standard uniform of the Canadian infantry,” wrote Pulsifer. “This meant surrendering their mackinaws, Mexican saddles, Colt pistols, and Stetson hats, which were put into stores, never to re-emerge.”

Boyle, meanwhile, had been made an honorary colonel by Hughes. Now able to wear a uniform, he festooned it with gold maple leaves.

Boyle’s agent in England, T.D. MacFarlane, was attending to the unit’s interests at the time. Pulsifer said MacFarlane “made a proper nuisance of himself” to authorities pushing what he perceived to be the detachment’s interests.

Now officially titled the Yukon Motor Machine Gun Battery, the unit was made up largely of men that were tough, self-reliant and determined.

In a July 26, 1915, letter to Brigadier General J.C. MacDougall, the commanding officer at Shorncliffe, Hughes’ senior representative in Britain, acting Major-General John W. Carson, wrote that “Mr. Boyle seems to have raised a small unit of sixty [sic] and thinks that they are entitled to every sort of consideration.

“I have told Mr. Macfarlane [sic] that we simply cannot and will not treat them as a separate unit.”

MacDougall subsequently attached the Yukoners to the much larger Eaton Motor Machine Gun Brigade, while allowing them to retain the title of “Boyle’s Battery.”

MacFarlane and the men of the battery seemed satisfied, wrote MacDougall. Carson replied that he “was glad you have everything running to the satisfaction of these very-hard-to-satisfy people.”

The Eaton marriage lasted seven months. Outmanned and ill-equipped, Pulsifer said “the Yukoners believed the personnel of the Eatons to be haughty and disdainful towards them, with the result that the Yukoners viewed their association with the Eatons as a period in purgatory.”

Captain Harry F.V. Meurling, eventual commander of the Yukons, brought depth of experience to the job, raising morale and expertise among his charges.

[LAC/3219317]

“Mr. Boyle would naturally like his patriotism rewarded by the Yukon battery being sent to the front,” he said. “Will you please have the Battery specially looked to with a view to their being sent to the front at the very first opportunity?”

Now officially titled the Yukon Motor Machine Gun Battery, the unit was made up largely of the kind of men that had come north in the gold rush of 1898—tough, self-reliant, determined, accustomed to a hard-scrabble life of prospecting the frontier.

While the average age of CEF recruits was 26 at enlistment, the original Yukoners averaged 33 years old. The oldest was 42, the youngest 22.

Most were Canadian-born, a departure from the CEF norm, where as many as 70 per cent in the war’s early years were British born. Eighteen, or 66 per cent, of the originals were Canadian-born. After the second group came in to replace those transferred out to other units, 13, or 54 per cent, were born in Canada. One of the foreign-born recruits was from Russia, another from India.

By the time the division’s first assault ended with a sizable portion of the trench in Allied hands, the Yukons had fired 300,000 rounds.

By July, they were in the Ypres Salient in western Belgium manning their newly issued Vickers machine guns as “E” Battery of the 1st Canadian Motor Machine Gun Brigade.

They were commanded by a decisive, innovative leader in Captain Harry F.V. Meurling, a Swedish-born civil engineer who had been a machine-gun specialist in the Swedish navy and served with Belgian forces in Congo. He immigrated to Canada around 1909 and had been seconded from 5 CMR to instruct machine-gunnery at the Canadian Military School in Shorncliffe before coming to the Yukons.

On Sept. 16, 1916, the unit covered a raiding party that penetrated enemy lines in a night mission. On Sept. 22, they opened fire on an enemy working party. “Enemy machine guns tried to locate our positions but failed,” reported the unit war diary.

In October, they were dispatched 50 kilometres southeast to Courcelette as part of the 4th Canadian Division during the Battle of the Somme.

With Courcelette already taken by the Canadians, they joined the Oct. 21 assault on one of the last major objectives of the whole bloody campaign, Regina Trench, a meandering German works on Thiepval Ridge behind the town.

They were ordered to open up at zero hour “with rapid intense fire, which is applied for 20 minutes,” said the war diary. “For the next 40 minutes fire is applied at the rate of two belts [250 rounds each] every five minutes.

“At 1:06 p.m. fire is slackened to one belt per five minutes. For two periods of ten minutes fire is increased to two belts in order to break up an enemy counter attack…. Fire is applied during the night to hollows from which attacks are expected all night.”

Soldiers test a Vickers heavy machine-gun. The water-cooled Vickers fired the standard .303-inch bullet (as did the Lee-Enfield rifle) from 250-round cloth ammunition belts. The Vickers could fire between 450 to 500 rounds per minute to a maximum range of 4,500 metres. It was an effective, reliable weapon but heavy and difficult to transport forward during a battle.

[CWM/19920044-674]

The fire had been so intense that one of them, Frank McAlpine, was hospitalized after he was overcome by the guns’ noxious gasses.

“The [Bosche] made a couple of futile counter attacks yesterday, but all easily repulsed,” the 4th Division’s commander, Major-General David Watson, wrote in his diary. “Capt. Meurling with his M.G. Battery did splendid work.”

A week later, Watson put Meurling in command of all 4th Division machine guns.

A second assault, on Oct. 25, failed. On Nov. 11, the artillery unloaded in force, pulverizing German-held positions along the trench. The attackers secured their objectives by mid-afternoon.

Meurling had 18 machine guns under his command. They fired 72,000 rounds between 1:30 and 2:30 p.m. on Nov. 10 and 130,000 rounds between 4:30 and 8 p.m. They maintained a “light” rate of fire from 11 p.m. until midnight, then resumed heavy fire at dawn. In all, they expended 530,000 rounds during the successful third assault.

While comprehensive casualty figures are hard to come by, just three of Boyle’s 46 originals returned to the Klondike in August 1919.

A week later, Meurling was commanding 40 guns and some 250 men as the 4th Division took Desire Trench, about 640 metres north of Regina, and more. It would be the last of the Canadian victories at the Somme.

They moved on to the relatively quiet Arras sector, by now skilled practitioners of “scientific machine gunnery.”

“This required the precise calculations of distances, heights, and angles, and also the use of carefully worked-out range charts,” wrote Pulsifer. “Such instruments of the surveyor as protractors, clinometers, and prismatic compasses became essential.”

The evolving techniques were used by Canadian machine gunners in 1917 at Vimy Ridge in April, Hill 70 in August and Passchendaele in October-November.

The Yukons fought at Vimy Ridge, Passchendaele, the Somme again in March 1918, Amiens and Canal du Nord on through the Hundred Days Campaign that ended the war. Thirteen of Boyle’s men were awarded Military Medals.

Medics tend to wounded in a trench during the Battle of Courcelette in mid-September 1916.

[ CWM/19920044-639]

Joe Boyle didn’t return either.

He had spent the last year of the war on clandestine operations against German and Bolshevik forces in Eastern Europe and southwestern Russia on behalf of Romania.

Working with a Russian-speaking member of the British secret service, the pair secreted the Romanian crown jewels and treasury out of the Kremlin and back to Romania. In March-April 1918, they rescued some 50 high-ranking Romanians held in Odessa by revolutionaries.

A confidant of Romania’s Queen Marie and a national hero to her people, Klondike Joe spent his last days in England, where he died in 1923. He was just 55 years old.

Advertisement