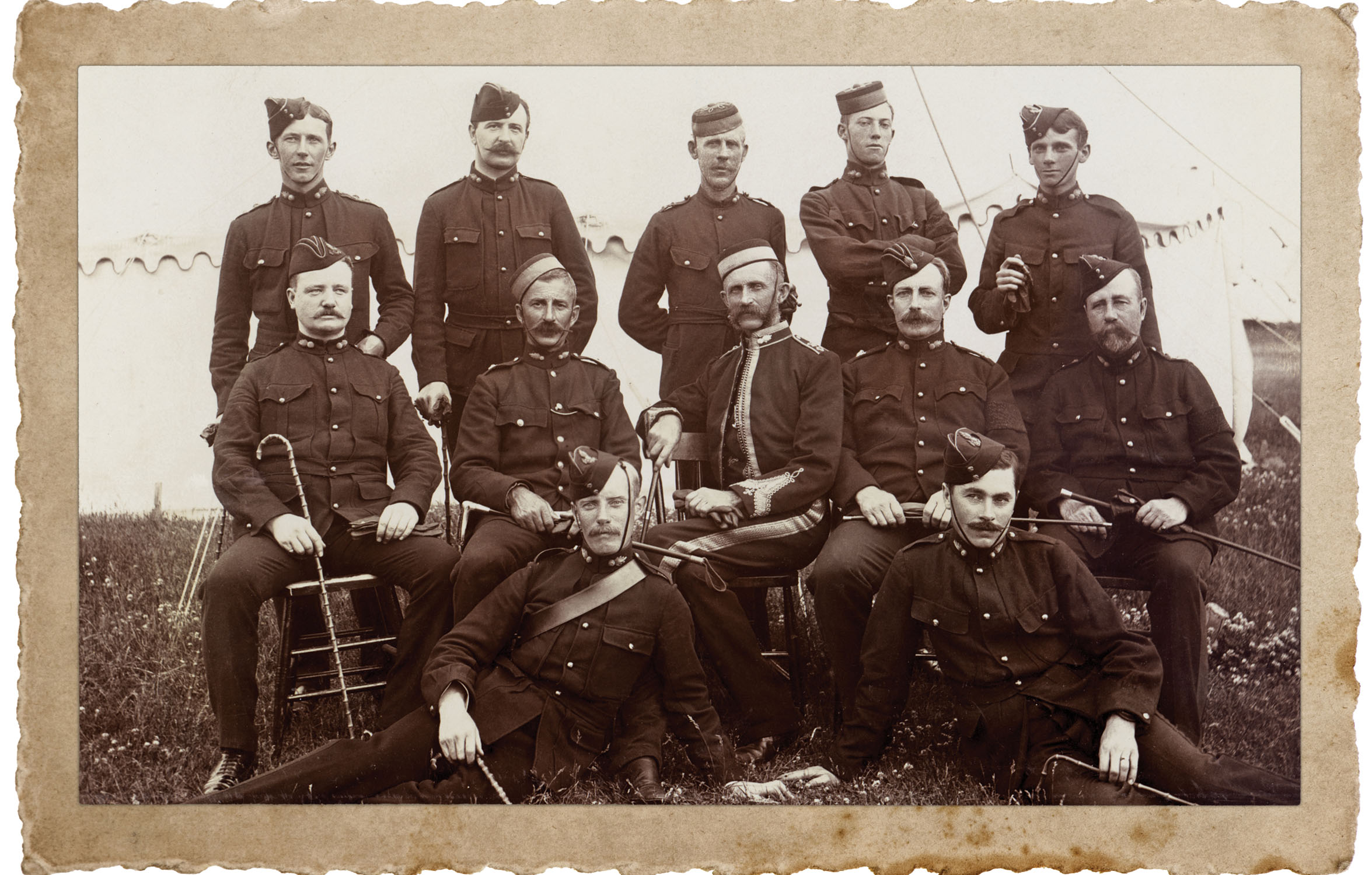

John McCrae (back row, at left) served in the Boer War as a lieutenant with the Canadian Field Artillery. [Guelph Museums/M1968X.353.1.1]

The Boer War started the year John McCrae graduated from the University of Toronto’s medical school. He had served as an officer in the military reserves and had a romantic view of war, partly gleaned from Rudyard Kipling’s vivid accounts of war as British adventure. He had pasted Kipling’s poem “The White Man’s Burden” into a scrapbook.

After graduating, McCrae was determined to go to South Africa. “Ever since this business began,” he wrote his mother, “I am certain there has been not 15 minutes of my waking hours that it has not been in my mind.… I shall not pray for peace in our time. One campaign might cure me—but nothing else ever will, unless it be old age.”

McCrae joined the Canadian volunteers as a lieutenant, and was assigned to lead D Battery. During his first week in Cape Town, he met Rudyard Kipling.

“Met the high priest of it all,” McCrae wrote. “He is little, fat like his pictures, & very affable. He says ‘Up country is just Hell.’ He told me I spoke like a Winnipegger.”

In mid-July, McCrae got his first taste of battle. “21 July 1900, Our baptism of fire,” he wrote in his diary. “They opened on us from the left flank.… One shrapnel burst over us & scattered on all sides of us. I felt as if a hailstorm was coming down & wanted to turn my back, but it was over in an instant.”

McCrae’s romantic ideas of war were stripped away by the realities in South Africa. More men died of disease than in combat. The field hospitals were a disaster.

“For absolute neglect and rotten administration, it is a model,” McCrae wrote. “I am ashamed of some members of my profession.… The soldier’s game is not what it’s cracked up to be.”

Britain was mired in South Africa, surprised by a stubborn enemy and its guerrilla tactics. McCrae was disillusioned by the battle there, and returned home before the British began burning Boer farms and putting civilians in concentration camps, where 25,000 died of disease or famine.

McCrae returned to his hometown of Guelph, Ont., to cheering crowds and a proud speech from the mayor, but his enthusiasm for war had withered. However, it wouldn’t be the last war for McCrae.

And 15 years later, he would go on to write a poem of his own, a more sombre reflection on war: “In Flanders Fields.”

Advertisement