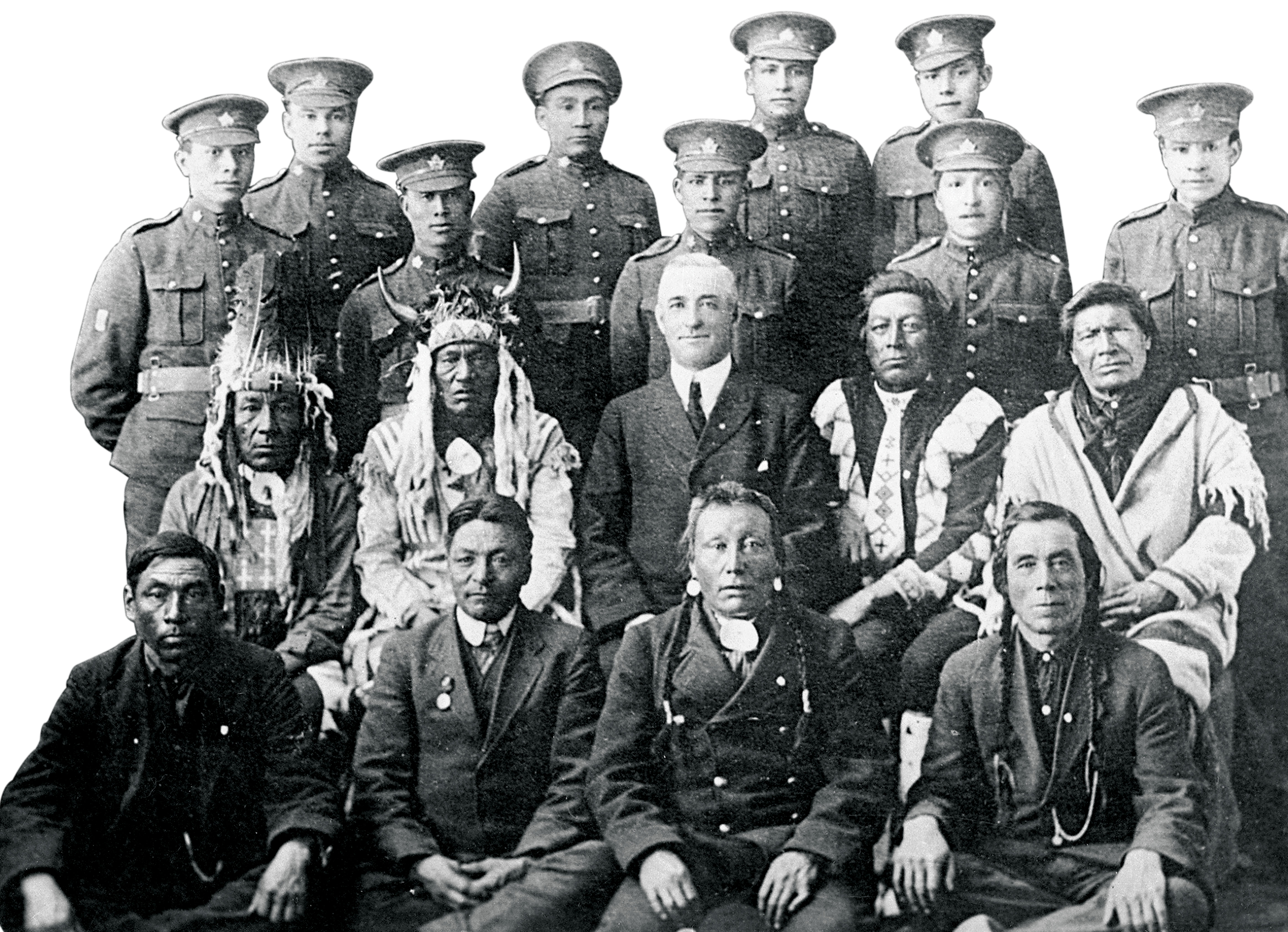

lders and soldiers (below) from the Peepeekisis (Cree), Standing Buffalo (Dakota), Okanese (Cree-Salteaux) and George Gordon (Cree) First Nations pose with W.M. Graham, inspector of Indian agencies in South Saskatchewan, circa 1916-17. [LAC/PA-041366]

Their ancestors fought beside the British in the Seven Years War and the American Revolution in the 1700s and in the War of 1812. In 1885, they navigated Africa’s Nile River on a British military rescue mission and volunteered for Canada’s first international expeditionary force at the dawn of the 20th century, fighting with the British in the Boer War in South Africa.

But when Great Britain called for aid during the First World War, the support of Indigenous Peoples—First Nations, Inuit and Métis—initially caught the Canadian government off guard.

Status Indians were “wards of the government and did not have the rights or responsibilities of citizenship,” wrote historian James Dempsey, who is of Kainai (formerly Blood) First Nation ancestry, in Aboriginal Soldiers in the First World War. “As such, they were not expected to take up arms.”

Unexpectedly, hundreds of status Indians did immediately enlist; by war’s end, thousands of Indigenous men had served. Just how many may never be known. About 4,000 status Indians, a third of all of enlistment age, signed up, but there is no official count of Métis, Inuit or non-status First Nations volunteers.

Not all First Nations people supported the war. Some cited treaty assurances that they would not have to go to war for Great Britain. Others first wanted recognition of their status as independent nations. Only 29 status Indians from Alberta are known to have served, 17 of them from the Kainai First Nation, according to A Commemorative History of Aboriginal People in the Canadian Military. When conscription was instituted in 1917, status Indians successfully fought for exemption.

But many First Nations people were enthusiastic supporters. Some volunteers travelled hundreds of kilometres, much of it by canoe, to enlist.

“Some reserves were nearly depleted of young men,” wrote Janice Summerby in Native Soldiers, Foreign Battlefields.

Every man between 20 and 35 from British Columbia’s Head of the Lake Okanagan Indian Band, now known as Nk’maplqs, volunteered. In New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, about half of eligible Mi’kmaq and Maliseet men enlisted. Hundreds from the Six Nations of the Grand River in Ontario volunteered.

What drew them to serve?

For some, it was a logical next step from militia service. Alexander G.E. Smith of the Six Nations near Brantford, Ont., a former captain of the Haldimand Rifles militia regiment, was commissioned as a lieutenant when he enlisted in 1914, aged 34, and rose to captain less than two years later. He earned a Military Cross in the Battle of the Somme. He helped capture an enemy trench and take 50 prisoners, despite being buried twice by shellfire. He was wounded three times before he was sent home, where he served out the war at a training camp.

Some saw it as their duty, offering “help toward the Mother Country in its present struggle in Europe,” as Chief F.M. Jacobs of the Chippewas of Sarnia Reserve, now the Aamjiwnaang First Nation, wrote in a letter.

“The Indian Race as a rule are loyal to England,” said Jacobs. “This loyalty was created by the noblest Queen that ever lived, Queen Victoria,” under whose name treaties were signed.

Others were drawn by the warrior ethic, which had been squelched by residential schools, reservation life and restrictive policies.

“When we were called forth to fight for the cause of civilization, our people showed all the bravery of our warriors of old,” said Mike Mountain Horse of the Kainai First Nation in Alberta. He fought near Vimy Ridge and in the Battle of Cambrai. After the war, he drew images of his experiences that were put on a cowhide warrior robe.

The Belanger brothers, Ojibwa of the Fort William First Nation in Thunder Bay, Ont., signed up together. They joined the 52nd Battalion and both became dispatch runners. Peter was wounded in action, Gus killed in May 1917. Gus had earned a Military Medal in June 1916 for carrying dispatches back and forth for 11 days across open country, under heavy shellfire, buried once by debris and twice coming under machine-gun fire.

Volunteers included those whose relatives fought in the 1885 Métis resistance against the Canadian government. Alexander Decoteau, a Cree of the Red Pheasant Reserve in Alberta, joined the Canadian Expeditionary Force in April 1916. His Métis father was a warrior of the Cree leader Poundmaker at the Battle of Cut Knife in 1885. Louis Philippe Riel, nephew of Métis leader Louis Riel, enlisted the day after war was declared. He was such a good sniper that he was assigned to eliminate enemy snipers. He is credited with 30 kill shots. Decoteau and Riel were both killed in battle.

Others traced the military footsteps of their brothers or forefathers. Charles Denton Smith, 22, followed his older brother Alexander into service in 1915, and was also immediately made a lieutenant due to his militia experience. He, too, became a captain and earned a Military Cross for leading a platoon in November 1918 that stopped enemy sappers just as they were igniting the fuse on a road mine.

A steady wage and regular meals were an incentive for those who struggled through the pre-war economic depression, lack of jobs and wartime inflation.

“We knew about the war overseas,” said Sam Glode, a Mi’kmaq lumberjack from Nova Scotia. “And we knew the Canadian army was paying $1.10 a day, besides your clothes and grub. So, John said to me, ‘Sam, let’s go to the war. It can’t be no worse than this.’”

And, of course, service was a clarion call to adventure for young men, some of whom had never seen a town or city. “Enlisting seemed to offer freedom and an escape from the confinement of reserves,” said Dempsey.

Indigenous soldiers went over with the first Canadian troops to Europe, fought in every great battle—Ypres, the Somme, Vimy Ridge, Passchendaele, the Hundred Days—and were employed in every trade.

Racism in the air force and navy kept most Indigenous men out of those services. Until 1943, Royal Canadian Navy policy stated that recruits had to be “of pure European descent and of the white race.” Despite this, an Indian Affairs report from 1942-43 listed nine status Indians in the RCN.

The Royal Canadian Air Force had high education standards that very few Indigenous people could meet. But at least three were accepted. Two Six Nations men—James Moses, a Delaware and Oliver Martin, a Mohawk—were seconded from the 107th (Timber Wolf) Battalion to become lieutenants in the Royal Flying Corps. Moses did not return from a mission and was presumed dead. Martin survived the war and rose to the rank of brigadier in the Second World War.

They were joined by John Randolph Stacey, a Mohawk from Kahnawake, who started out in the 114th Battalion. In 1917, he wrote in a letter to the Lord Provost of Glasgow: “The Indians from Canada whom you entertained are now really doing the job for which they came over, and are prepared to see the matter to a finish.” Stacey became a pilot in the Royal Air Force and was killed in a crash in 1918.

In the infantry, many Indigenous soldiers served as scouts and snipers, using their experience in hunting and tracking. Athletes, including Olympians Tom Longboat, an Onondaga from the Six Nations of the Grand River, and Alexander Decoteau, a Cree of the Red Pheasant First Nation in Saskatchewan, were runners, sprinting between front line and headquarters delivering orders and intelligence. Indigenous troops also served in construction and mining companies and helped build and maintain trenches and railways.

There were no all-Indigenous regiments, but several battalions did have many Indigenous members.

The 114th (Haldimand) Battalion had about 350 Indigenous soldiers, most from the Six Nations and the Kahnawake and Akwesasne communities in Quebec. Two of its companies were headed by Indigenous officers. The battalion, sometimes called the Indian Unit, is also known as Brock’s Rangers, in honour of Major-General Sir Isaac Brock, with whom Indigenous soldiers fought in the War of 1812.

[CWM/19920166-1734]

In Winnipeg in 1915, Lieutenant-Colonel Glen Campbell, the son of a fur trader married to the daughter of an Ojibwa chief, raised 1,000 men, half of them Indigenous, for the 107th Battalion.

The 107th became a pioneer battalion, its fighting infantry also given some engineering jobs, including tunnelling, mining, railway work and trench maintenance. In the Battle of Hill 70, men of the 107th followed assault troops across no man’s land to dig communications trenches in captured territory, under fire and exposed to poison gas.

More than 300 Indigenous soldiers were killed and thousands wounded in the war. Many returned with lungs scarred from poison gas, and with tuberculosis and Spanish influenza, which claimed many victims in First Nations communities across Canada.

For the most part, Indigenous soldiers were accepted as brothers-in-arms and treated equally. But they returned home to find the same discrimination as before the war, and little appreciation in wider society of their wartime service and sacrifice.

“The sacrifice of killed and wounded achieved very little politically, economically or socially for them,” wrote military historian Fred Gaffen in Forgotten Soldiers.

Frederick Loft founded the League of Indians of Canada after the war. [LAC/PA-007439]

Status Indians lost their temporary right to vote once they took off their uniforms. They had to seek benefits from the Department of Indian Affairs instead of through the Department of Veterans Affairs, as other veterans did. They did not have equal access to veterans’ benefits, particularly land and grants to establish farms.

“The Canadian government’s view was that, as status Indians, they were already receiving government support not available to other Canadians, and that it would be unfair for them to receive the additional support provided to other veterans,” said the 2019 Standing Committee on Veterans Affairs report Indigenous Veterans: From Memories of Injustice to Lasting Recognition.

In response, the League of Indians of Canada formed. “We have performed dutiful service to our King, Country and Empire and we have the right to claim and demand more justice and fair play as recompense,” said founder Frederick Ogilvie Loft, a Six Nations Mohawk.

“The most significant benefit of Aboriginal peoples’ war service was interaction between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people, which was not common in general Canadian society prior to the war,” says a passage in For King and Kanata: Canadian Indians in the First World War by historian Timothy Winegard, who is of European and First Nations heritage and served in the CAF.

“By serving alongside Aboriginal soldiers, Canadian soldiers came to better understand Aboriginal people, and to overcome many negative stereotypes.”

That is still true today.

George McLean (opposite) was a descendant of chiefs and an outlaw. [av.canadiana.ca]

George McLean (opposite) was born in Kamloops, B.C., in 1875, of noble lineage through his mother to chiefs of the Douglas First Nation and Okanagan and Nicola Valley peoples. His father was Allen McLean, a descendant of one of Scotland’s oldest clans and a member of the Wild McLean Boys, an outlaw gang infamous for robbery and rustling and all of whom were hanged for murder.

George served in the Boer War with the Canadian Mounted Rifles. In 1916, at the age of 41, he volunteered again and served in the 54th (Kootenay) Infantry Battalion, which fought at

the Battle of Vimy Ridge.

On the third day of the battle, McLean carried a wounded officer off the field, then returned to the fight. He started lobbing Mills bombs (grenades also called pineapples) into a German dugout until one of the men inside asked how many soldiers were with him. McLean, lying, said 150. The Germans surrendered and McLean used their sergeant-major’s own weapon as he marched the prisoners to captivity. “Single-handed, he captured 19 prisoners,” reads the citation of his Distinguished Conduct Medal.

After the war, McLean returned to ranching, then became a firefighter. He died in 1934.

[Wikimedia]

The evening before the Battle of Messines in Belgium in June 1917, British General Sir Charles Harington said, “I don’t know whether we are going to make history tomorrow, but at any rate, we shall change geography.”

Sappers had dug a series of deep mines under Messines Ridge to the German lines, then packed them with 454 tonnes of explosives. At 3:10 a.m., June 7, they were detonated, killing an estimated 10,000 German soldiers.

Sam Glode, a Mi’kmaq from Nova Scotia, watched the fireworks, the fruit of two years of dangerous and hard labour by British and Canadian tunnelling companies.

“The ground shook to and fro like it was shivering,” Glode said in a 1983 article in Cape Breton’s Magazine. “Then we saw flames shoot up high in the dark over the ridge. Then the guns opened up, hundreds of guns. That was some noise, I tell you. Along towards daylight the infantry went over no man’s land and up the ridge. I guess they didn’t find many Germans in any shape to fight, because they took the ridge easy.”

He could very easily have missed the show due to German counter-tunnelling, said Glode, who joined the No. 1 Canadian Tunnelling Company in 1916.

Because the ground sloped downward from the Canadian front line to no man’s land, Glode and his fellow miners had to dig straight down about 35 metres before they could tunnel horizontally toward the ridge.

“All of a sudden everything went black. I felt like somebody had hit me on the head with a big club…. When I came to my senses…my ears were singing like a steam whistle was inside them…. I noticed the air was very bad and when I tried to light a candle, it wouldn’t light.” The air pipe was no longer pumping fresh air.

“I figured our only chance was to dig up to the surface.” But the others in his crew, all former coal miners, “couldn’t think of anything but that 80-foot shaft straight down.”

Glode, however, knew it was not that far. “It’s something to be an Indian, after all. You look at a piece of country and it’s like a picture in your mind. I remembered the long dip of the ground between our front-line trench and the Germans. I keep picking away, the air got worse and worse…. At last, I struck with a shovel and went through turf and there was daylight and a rush of cold air.”

But he had come up in no man’s land. The trapped tunnellers were waiting for nightfall to chance an escape when they heard a tapping sound from the collapsed air pipe—a rescue party.

After a few days’ rest, the crew started again. “The whole job took about a year,” said Glode. “We then worked for 20 days carrying explosives in metal boxes that must have weighed about 50 pounds [23 kilograms] each. We knew the tunnels were to be blown. When the time came, we were all watching from the top of a little hill.”

Glode’s work won him promotion to sergeant. After the war, he returned to guiding hunting and fishing parties. He died Oct. 25, 1957, at Camp Hill Hospital in Halifax, aged 79.

[CWM/19920166-1734; 19710261-0440]

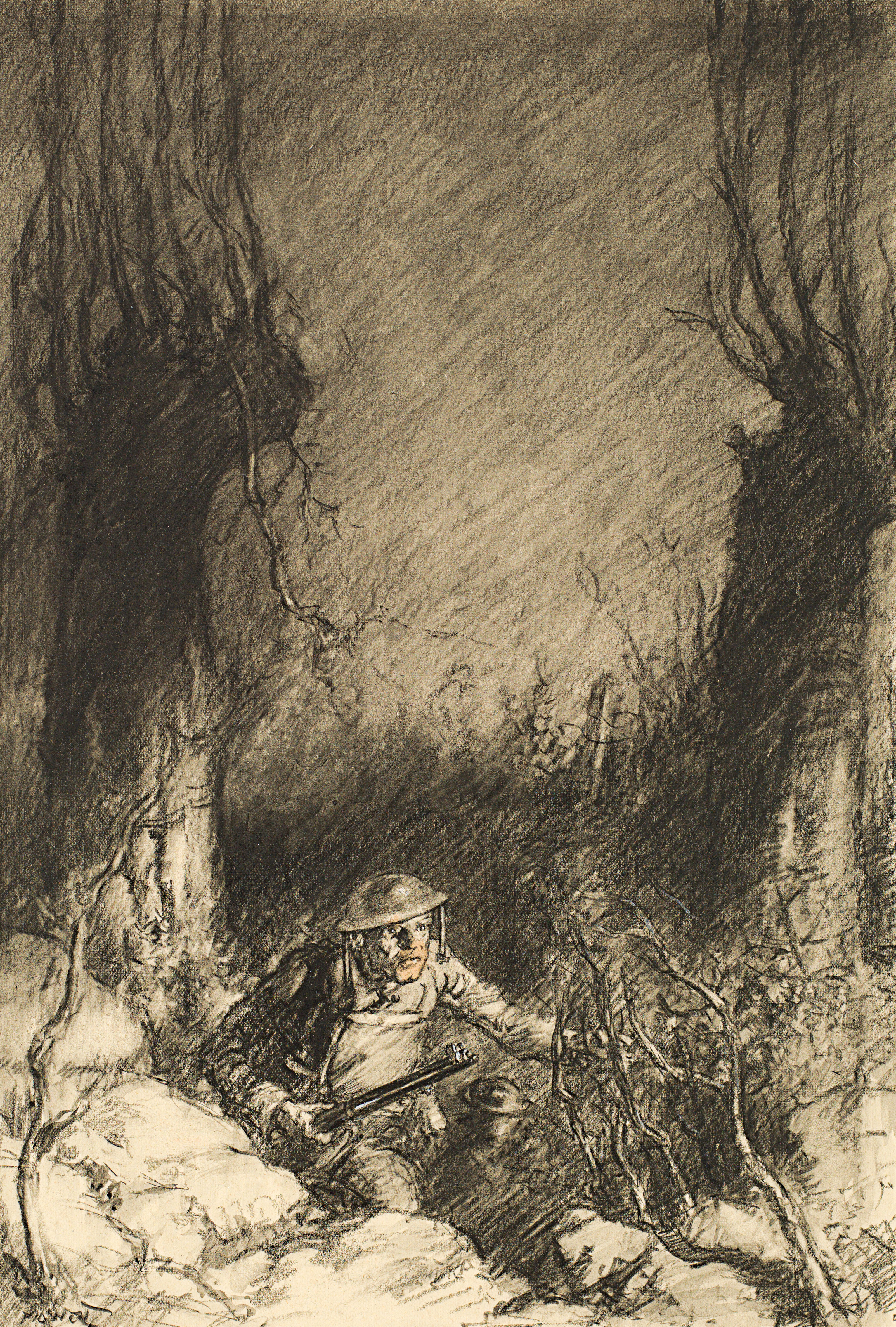

The scars covering Joseph Roussin’s body attested to the dangerous work of reconnaissance scouts. Scouts left the safety of the trench to get information about the enemy: where they were, in what strength, and with what weapons.

Lumberjack Roussin, a Mohawk from Kanesatake in Quebec, enlisted in 1915 and served in the 22nd (French Canadian) Battalion, affectionately nicknamed the Van Doos. He carried out a single-handed attack against eight enemy soldiers in the Battle of Hill 70 near Lens, France, on Aug. 15, 1917, killing five, taking three prisoners, and earning the Military Medal.

“One of the scouts from the Van Doos has been wounded,” says a translation of Joseph Chaballe’s Histoire du 22e Bataillon. “Roussin, an Indian, is

the most wounded man in the regiment, perhaps the entire British Army. This one will earn him a ninth wound stripe…he’s patched up and heads back to his post!”

[Veterans Affairs Canada archive]

Isolation prevented many Inuit from enlisting, but it is estimated that at least 15, mostly from Labrador, served in the 1st Newfoundland Regiment, mainly as snipers and scouts.

John Shiwak, a hunter and trapper from Rigolet, Labrador, enlisted in the Newfoundland Regiment in 1915, trained in Scotland and arrived in France in July 1916. He served as a scout and sniper for 15 hellish months, his expertise as a marksman earning him promotion to lance-corporal in April 1917. But the experience took its toll. He confided to a friend that he was depressed and sickened by the killing.

“He was shy and lonely,” recalled comrade Howard Morry. “Often he’d say ‘Will it ever be over?’ He sure was a great shot and had a lot of notches on his rifle. He said sniping was like swatching seals”—scanning open water or ice for surfacing seals.

In the Battle of Cambrai in November 1917, a shell fell among a company walking along a canal bank, wounding 10 and killing seven, including Shiwak.

[Wikimedia; Courtesy of Marilyn Buffalo]

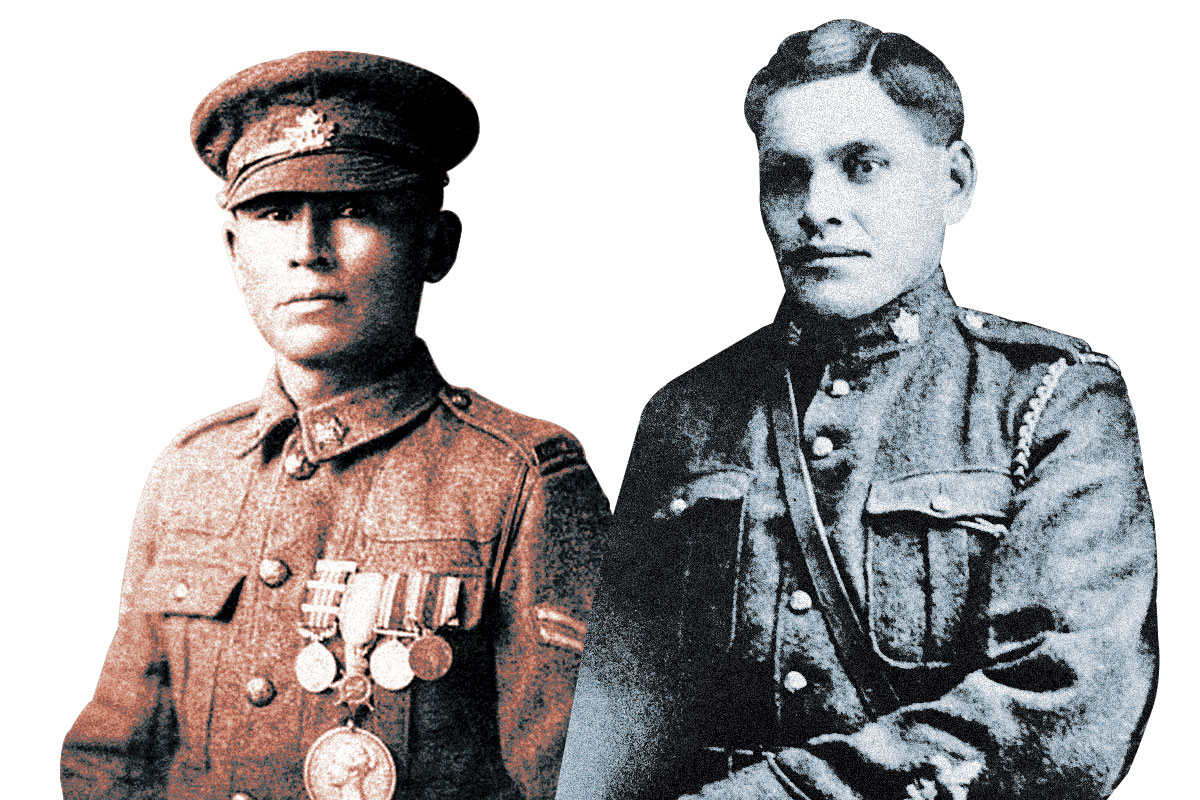

An Ojibwa from Wasauksing (formerly Parry Island) First Nation in Ontario, Francis Pegahmagabow (right, at left) was in rare company indeed at the end of the First World War, one of only 39 men in the entire Canadian Expeditionary Force to receive the Military Medal with two bars. He was a deadly sniper.

Pegahmagabow earned his first Military Medal in 1916 at the Battle of Mount Sorrel for capturing a large number of prisoners. His first bar was earned at Passchendaele, his second after the Battle of the Scarpe in August 1918 when he went over the top under machine-gun fire to bring back ammunition for his company.

He was, perhaps, the deadliest sniper on either side. He is credited with 378 kills and the capture of more than 300 prisoners.

Pegahmagabow is often remembered for his achievements, but few know of his suffering. He had a long war. A member of the first contingent to go overseas in 1914, he was discharged in 1919, after spending time invalided. He was gassed in Ypres in April 1915 and had lifelong lung problems. He was wounded on the Somme in 1916, suffered bleeding from the ears, was buried three times and thrown by an explosion once, developed pneumonia, had a hernia and was diagnosed with melancholia and exhaustion psychosis, what we now call depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. On top of it all, he complained of persecution by his company sergeant major.

“He claimed to his comrades, who nicknamed him Peg or Peggy, that a medicine bag presented to him by an elder would give him a charmed life overseas. He was right,” wrote historian Fred Gaffen in Forgotten Soldiers.

Pegahmagabow’s battles did not end with the war. His fight for the rights of his people and Indigenous veterans carried on for the rest of his life. He died of a heart attack in 1952.

Henry Norwest (above, at right), a Cree homesteader and rodeo performer in Alberta, was also a deadly sniper, with 115 confirmed kills, and likely many more.

Norwest earned the Military Medal at the Battle of Vimy Ridge, where he “showed great bravery, skill and initiative in sniping the enemy” and saving a great number of lives, reads the citation.

Norwest and Pegahmagabow both courted constant danger as snipers. While many other snipers fired from the trenches or from the rear of the front, these two crept out into no man’s land and waited for opportunities.

Norwest once waited two days to pick off two enemy snipers terrorizing his company. His reputation was great, even among the enemy: captured Germans spoke of the fear he provoked in their trenches.

“Norwest was quite naturally one of us,” said a comrade. He was nicknamed Ducky because he told comrades he ducked (avoided) all the women he met in England. He is described as quiet, reserved and fatalistic.

During the Battle of Amiens in August 1918, Norwest told a comrade he believed he would soon die. He fell on Aug. 18 while trying to find a German sniper’s nest: the enemy sniper found him first.

“It must have been a damned good sniper that got Norwest,” his comrades inscribed on his grave marker.

Norwest was posthumously awarded a bar to his Military Medal “for gallantry in the field,” says the citation.

[The Canadian Encyclopedia]

Charlotte Edith Anderson Monture wanted to be a nurse, but as a Mohawk woman from the Six Nations of the Grand River in Ontario, her options were limited by prejudicial policies of the day. Turned down by nursing programs in Canada, she trained in the United States.

Anderson graduated first in her class in 1914, and began her career at a private school in New York. When the U.S. entered the war in 1917, she volunteered to serve overseas, one of 14 Indigenous nurses in the U.S. Army Medical Department.

Before she deployed, her family gave her ceremonial Mohawk clothing in which she could be buried should she die overseas. She served at Buffalo Base Hospital 23 in Vittel, France, where, her diary notes, her unit performed 50 operations in one day, on July 6, 1918.

Her memories of the war remained vivid all her life. “It was an awful sight—buildings in rubble, trees burnt, spent shells all over the place, whole towns blown up,” she recalled in an interview in 1983. She still mourned the deaths of her patients.

After the war, Anderson returned to the Six Nations community, married, raised children and nursed part-time. She died in 1996, aged 105.

Advertisement