![. [PHOTO: ©iStockphoto/laflor] . [PHOTO: ©iStockphoto/laflor]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/ImproveLead.jpg)

When people enter the home of Derek and Maria Lunden in North Vancouver or the home of Alison and Peter Faid in Edmonton, they are impressed by roomy kitchens and bathrooms, wide doorways and hallways, fine finishings and lots of natural light. What isn’t so obvious is that these private homes were designed to help their owners negotiate through the later stages of life, whatever life throws at them.

The Lundens and Faids are pioneers in using housing to help them age in place, a concept that will become very familiar over the next few years as baby boomers move through retirement. “Probably the most significant demographic trend of the last 50 years is that people are living alone and living longer, says Dr. Andrew Sixsmith, director of the Gerontology Research Centre at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver. Baby boomers are poised to change how we go about living alone longer, more safely and more comfortably.

Housing to support aging in place is a worldwide phenomenon spearheaded in Canada by baby boomers, says Dr. Don Shiner of Mount Saint Vincent University in Halifax. Canada’s baby boomers are preparing for retirement by converting cottages, renovating existing homes or building new homes for retirement. More and more of these houses have universal design features which allow everyone—grandparent to grandchildren—regardless of age, size or physical abilities to easily use every room. With an independent mindset, technological savvy and with more wealth than previous generations going into retirement, it’s expected that boomers will embrace not only housing built or renovated to suit their changing physical needs, but will also use the growing array of technological assistive devices to make up for diminished physical and mental capabilities as they age.

But what about those who’ve already retired? “About 94 per cent of seniors stay in their own homes—sometimes making do in terribly designed spaces,” says Shiner. While not everyone has the resources to design and build a dream home or do extensive renovations, even those on modest budgets can borrow ideas from the big spenders, says Edmonton architect Ron Wickman, who grew up with a dad in a wheelchair, and now specializes in accessible and universal design.

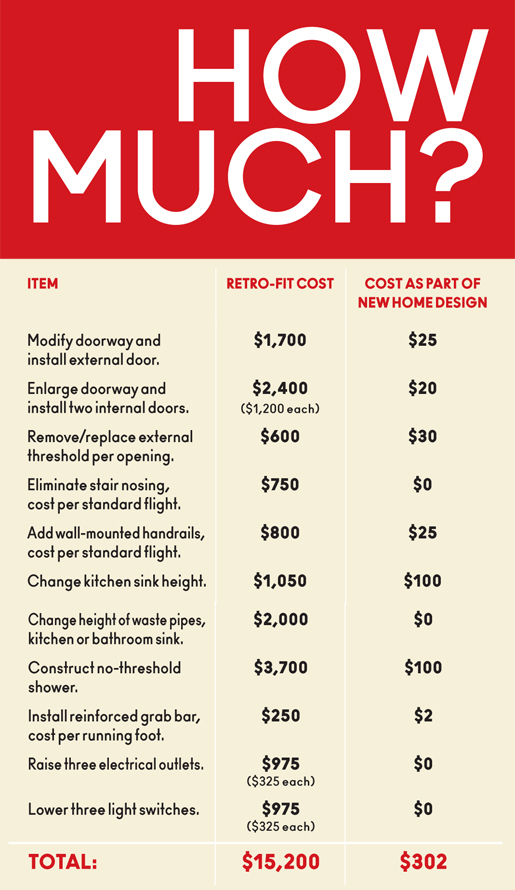

Depending on which items are chosen from the menu, universal design incorporated at the planning stage increases the cost of a new building from less than one per cent to about three per cent “and it doesn’t matter if the house is a million-dollar home or costs $250,000,” Wickman says. For instance, someone with no spending restraints may choose to make the whole house accessible to everyone in it by adding an elevator; someone on a much smaller budget may choose to design a one-level home, or widen the staircase in case they want to add a stairlift later; a third person may build a home with a main floor bedroom and accessible bath to accommodate older occupants. Similarly, allowing everyone to get in and out of the house easily may be achieved on a big renovation budget by providing an exterior lift to the entry level, while a ramp and entry-level door suits a smaller budget. The important point is to take the time to plan for or factor in future requirements.

The Faids’ $600,000 new dream home incorporates many universal design bells and whistles; the Lundens bought an older home on a flat lot and spent $120,000 in three renovation projects spread over a decade. Their ideas are indicated in this story in red ink and correspond to photos demonstrating how various homeowners have adapted similar universal design elements into their houses.

After Derek was diagnosed with progressive multiple sclerosis, the Lundens bought a modest bungalow for $275,000 in 1998 to renovate in stages, as budget permitted and Derek’s needs grew. Entry thresholds were removed and interiordoorways widened, hardwood flooring added, and showers with no thresholds created. In the kitchen, meal preparation, cooking and clean-up from a wheelchair is made easier by a pantry with roll-out drawers and a lower working surface, including a simple pull-out chopping board. Small cut-outs in lower cabinetry allows Derek to get his knees underneath the sink to do dishes; when he’s done, he closes the cabinet doors and the kitchen looks like any other. Costs were kept down in the kitchen renovation by adapting standard cabinetry.

A 400-square-foot addition provides a roomy master suite where supportive equipment can be tucked out of sight. Although Derek, 54, is now in a wheelchair, he wanted a home that didn’t look as though it had been designed for someone in a wheelchair. Many of the universal design concepts that support aging in place can be found in accessible housing for those with disabilities. The difference is that the aging-in-place concept recognizes the benefit to anyone living in any type of housing, not just in accessible housing or in long-term care facilities. “My house is designed in such a way that all the features I need are there, but they’re features anyone would enjoy.”

The Lundens intend this to be their last home. Some retiring seniors move into condos to live in a place they love, have a more accessible home, to downsize, have less home maintenance or enjoy luxury upgrades. The Lundens have all that now. “People ask me ‘are you going to move to a condo?’ and I say ‘I live in a 1,700-square-foot ‘condo’ with a great yard and garden and no condo fees.”

While the Lundens renovated to suit developing needs, the Faids built a luxury dream home with features to support what they think they might need in the future, but which come in handy today.

A consultant helping develop Edmonton’s aging-in-place strategy, Peter Faid found when he held committee meetings in the family’s previous home, which had six levels and 62 steps, “the only way some people in wheelchairs or walking with sticks could come into the house was to be carried in.” Recognizing that they too might have mobility issues in the future, the Faids decided to build a new dream home to last the rest of their lives.

Windows stretch to 18 inches from the floor, providing plenty of natural light—a boon to those with failing eyesight or who want a view from a wheelchair. Cushy cork floors were installed and area rugs removed to lessen tripping hazards and provide a hard surface for walkers or wheelchairs. Lever-type door handles are easier on arthritic hands; people with mobility issues find the higher toilets easier to use; people with balance problems can use the fashionable teak bench to sit while showering. “We were determined to have a fully accessible house,” explains Faid. But the $225,000 lot they bought would not accommodate a large bungalow, so they built a multi-level home with flush exterior thresholds. They installed a $22,000 elevator in case someone developed mobility problems, but find they use it every day for such chores as bringing groceries up to the kitchen, hauling laundry to the basement or moving furniture around.

Faid believes universal design will eventually become standard. “It’s like the old-fashioned potato peeler. It was narrow and metal and as you got older and arthritic, you couldn’t hold it. So someone came up with the larger handle and everybody found it easier to use. Now it’s the standard.”

In the past five years demand has picked up across the country for new housing and renovations incorporating universal design, says Peter Briand, chairman of the renovators council of the Nova Scotia Homebuilders’ Association and president of Econo Renovations Ltd. in Dartmouth. The upscale Fairwinds development in Nanoose Bay, just north of Nanaimo, B.C., on Vancouver Island, offered such age-in-place options as stacked closets ideal for later conversion to an elevator shaft. In Winnipeg, the province is working with developers of the Bridgewater Lakes development in the Waverly West neighbourhood to make at least half the 1,100 homes ‘visitable’ with flush entryways, wider hallways and accessible bathrooms. A 19-home development in Lawrencetown in Dartmouth, N.S., offers “tech-ready” housing that accommodates a range of entertainment, assistive and medical monitoring devices. Homes here will cost from about $275,000 up to $350,000, depending on upgrades.

Across the country more and more architects, developers, builders, renovators and health-care professionals are training in universal design principles. Many have trained in the United States and become certified aging-in-place specialists. The Nova Scotia Homebuilders Association hopes to offer certified aging-in-place specialist courses within the next year, says Paul Pettipas, executive director of the Nova Scotia Home Builders’ Association.

Vancouver, considered Canada’s retirement mecca, has a critical mass of architects, developers, renovators and researchers involved in promoting universal design and assistive technology for aging in place. In 2004, the SAFERhome Society was founded to develop certified building standards for universal, accessible housing. “Aside from the aging and accessibility issues,” says Patrick Simpson, society executive director, “these homes are safer for everyone.” Up to 80 per cent of admissions to the B.C. Children’s Hospital are due to preventable accidents in the home, he says. Fall-related injuries among the 65-plus population cost $2.8 billion a year, and the Public Health Agency of Canada estimates cutting the number of falls by one-fifth would result in 7,500 fewer hospitalizations, 1,800 fewer permanently disabled seniors and savings of $138 million a year.

SAFERhomes standards “work within existing provincial and national building codes,” adds Simpson. Planning universal design elements into a new home is very inexpensive—about “the cost of a carpet upgrade,” he believes. At the planning stage many changes, like raising or lowering electrical switches and outlets and plumbing and grouping the electrical, telephone, cable and security services together, cost nothing or very little. Others are relatively inexpensive, like adding wider doors (although the doors cost more, the cost is offset by the lower cost for studding and wallboard).

The society gives consumers peace of mind, he says, because if they stipulate SAFERhomes standards in their building contracts, the society can inspect the work to ensure standards are met and certify the house.

Interestingly, universal design is a component of many Legion seniors and veterans housing, says Dave MacDonald, consultant with the Legion Housing Centre for Excellence. The Legion has advocated that components be incorporated in private construction, too, recommending governments increase funding for home adaptation for seniors independence.It has also advocated for more supportive, affordable housing.

People wishing to build or renovate homes incorporating elements of universal design can find useful information in publications produced by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. The CMHC website has downloadable publications, including a series on FlexHousing, homes that adapt to the changing needs of families, and Accessible Housing by Design, with articles on planning renovations, universal design features room by room, and home automation features.

Canadians already have the renovation habit. The 2010 CMHC Renovation and Home Purchase Report states over 2.1 million households spent $25.8 billion on renovations in 2009, and 30 per cent of households headed by those 65 or older intended to renovate in 2010. Homeowners can cut costs by incorporating universal design features during home update renovations planned over time, and choosing options that fit their particular needs and budgets. But first they have to know what’s on the menu, says John H. Friswell, president of CCI Renovations in North Vancouver and a certified aging-in-place professional who believes it is best for people contemplating a renovation to seek out professionals familiar with aging-in-place concepts. Very few of his clients ask for universal design, but incorporate it when informed it can make aging in place easier, and increase the value and marketability of their home.

“Boomers have the mindset and the resources,” to incorporate universal design and assistive technology into renovations, says Nancy Paris of Peak Interiors in Vancouver, a biomedical engineer with 20 years of experience developing assistive technology. “I have clients who say ‘instead of going to Hawaii this year, I’ll do a reno so I can live in my house for the next 20, 30, 40 years.’” Planning ahead can cut costs, she says. Putting plywood behind drywall in kitchens and bathrooms during renovations saves thousands down the road if the need arises for bathroom grab bars or upper kitchen cabinets that can be raised and lowered mechanically. It doesn’t cost much to plan for base cabinets of several different heights, and adjustable-height sinks and countertops can be had for the same price as a kitchen island, Paris says. Inexpensive additions include raising the dishwasher and laundry appliances, lowering the microwave oven and replacing appliances with universal design options: refrigerators with freezers on the bottom, ovens with doors that swing to the side, front-loading laundry appliances. Adapting standard cabinets and buying pantry units or base cabinets with drawers instead of shelves also shaves costs. (The CMHC offers programs, such as the Residential Rehabilitation Assistance Programs for low-income earners and those with disabilities, to defray the cost of some renovations).

These experts also caution that not everybody needs every gizmo in every room in the house. Shiner says all many people will need is a level entryway, an accessible main floor bathroom and a main floor room that can be converted into a bedroom. Wickman advises anyone considering building or renovating a home to first consult the CMHC website to determine which features suit budget and need, then search out architects and contractors familiar with universal design and aging in place.

Aging in place isn’t just about personal preference—it’s also a public health issue. Aside from eliminating many hazards that cause accidents, universal design standards could save our social support network millions of dollars in long-term care. By 2031, a quarter of Canada’s population—about nine million people—will be 65 or older, according to Statistics Canada projections. Approximately seven per cent of older adults now live in long-term care facilities. There are about 280,000 spaces in these facilities. It is expected that by 2038 we’ll need 690,000 spaces, but the Alzheimer Society of Canada believes there could still be a serious shortfall of 157,000. That shortfall could be alleviated by helping more people stay safely in their homes as they age. “People suffering from cognitive impairment or problems with mobility and eyesight manage in familiar surroundings much longer,” says professor emeritus Gloria Gutman, head of Simon Fraser University’s gerontology department in Vancouver from 1982 to 2005. “I tell people to stay at home as long as you possibly can; that’s how you maintain control of your assets and your lifestyle. But if you’re telling people to stay at home, you have to tell them it’s OK if they have a few dollars saved up to spend on features to help them do the things they like to do and maintain independence.”

Wickman believes the federal government should offer tax incentives for universal design renovations. “We have incentives for people to make their houses more energy efficient. The government understands that if our homes are more energy efficient, our society as a whole will benefit, and it’s the same with aging in place.”

Email the writer at: writer@legionmagazine.com

Email a letter to the editor at: letters@legionmagazine.com

Advertisement