German admiral Karl Dönitz (in dark coat), followed by Colonel-General Alfred Jodl (at left) and Minister of Armaments and War Production Albert Speer, under arrest by British officers in 1945. [Capt. E.G. Malindine/No. 5 Army Film and Photographic Unit/IWM]

Given his obsessive, hands-on leadership, intolerance of failure, and penchant for brutal punishment, it had to be more than a little disconcerting when an infuriated Adolf Hitler learned details of a major sea battle from a British news agency hours before his own admirals told him about it.

Der Führer was so angry that he scrapped the German high-seas fleet in the midst of the Second World War. Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, who had commanded the Kriegsmarine for 14 years, would surrender his post to Admiral Karl Dönitz, head of Germany’s vaunted U-boat fleet.

Caught in the middle of this uncomfortable circumstance was Vice-Admiral Theodore Krancke, naval liaison officer at Hitler’s command headquarters in 1942-43. Krancke’s account of the debacle is stored in Allied archives.

Hitler was already fed up with his surface navy by the time Allied convoy JW-51B left Loch Ewe in Scotland on Dec. 22, 1942. The 15 merchant ships were headed for Murmansk, USSR, with a close-escort group consisting of a minesweeper, two corvettes and two armed trawlers, supported by six patrolling Royal Navy destroyers.

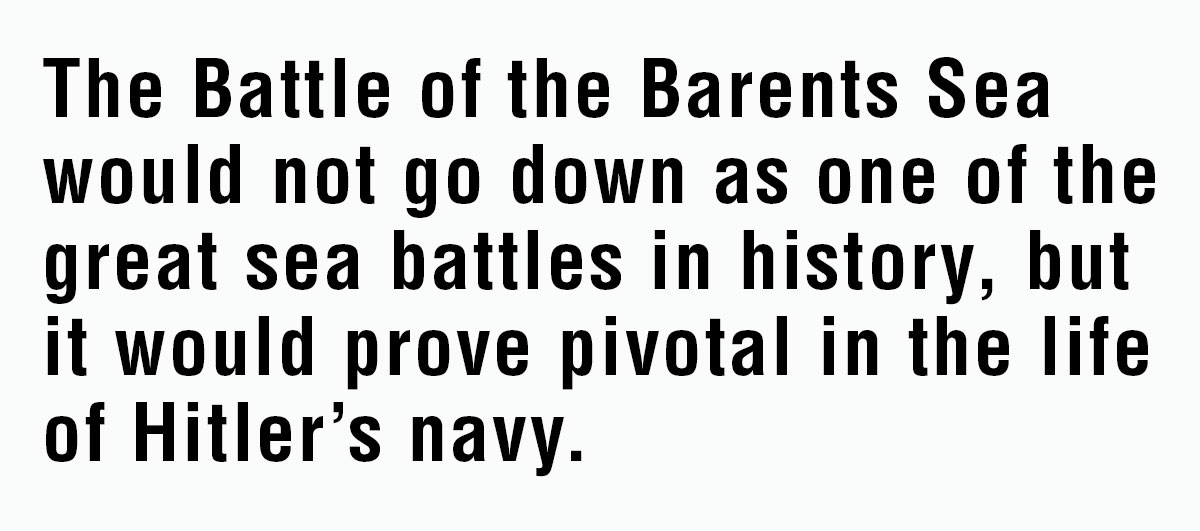

The Battle of the Barents Sea would not go down as one of the great sea battles in history, but it would prove pivotal in the life of Hitler’s navy.

Things had not been going well for Raeder’s Kriegsmarine. While the U-boats had enjoyed early successes against Allied convoys, the advent of sonar technology, stronger escorts and evolving tactics had begun to turn the tide in the Battle of the Atlantic.

Upon leaving his post as commander of the Kriegsmarine in 1943, Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, pictured in 1940, told senior staff that “without the success of the navy there can be no final victory.” Raeder would be proven right. [Bundesarchiv, Bild/146-1980-128-63/CC-BY-SA 3.0]

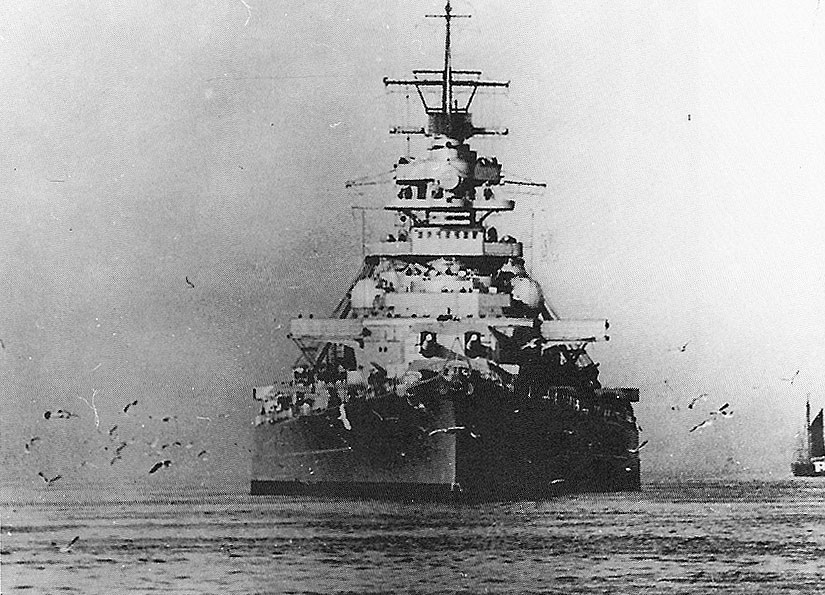

The surface fleet was in particular crisis. Under-equipped and without an assertive mandate, it had lost key battles and taken heavy losses early in the war, including the sinking of the battleship Bismarck, and it now found itself in ill-repair and at odds with other services.

At a Dec. 30, 1942, meeting, an exasperated Hitler lauded “the superiority of the British navy which was able to sail through the Mediterranean without paying any attention to the Italian Navy and Axis Air Forces,” Krancke reported.

He described “our own navy as but a copy of the British and a very poor one at that. The ships are not in operational readiness; they are lying idle in the fjords, utterly useless like so much old iron.”

Krancke did not challenge his boss but instead informed him that JW-51B had been discovered by a German reconnaissance aircraft and was being shadowed by U-354. The Northern Cruiser Task Force had set out to intercept it. The operation—called Rainbow or Unternehmen Regenbogen—was expected to encounter the convoy by early morning, Dec. 31. Hitler’s interest was piqued.

“The Führer emphasized that he wished to have all reports immediately, since, as I well know, he cannot sleep a wink when ships are operating,” Krancke wrote. “I passed this message subsequently to Operations Division, Naval Staff, requesting that any information be telephoned immediately.”

On New Year’s Eve morning, Krancke reported that the task force was in contact with the enemy in Arctic waters. By 11:59 a.m., the action had ended and the German ships had withdrawn to the west.

“I also gave a submarine report of 11:45 according to which the action apparently had reached a climax, since only a red glow could be seen in the arctic twilight. The Führer and I believed that in the main the attack on the convoy had come off according to plan.”

There were no details of the battle’s outcome, however, and, calculating their speed by the time of their projected rendezvous (at least 20 knots), Krancke optimistically concluded his ships, operating under radio silence, were undamaged.

“During the evening situation conference I received a Reuters report of a naval engagement (one destroyer sunk, one cruiser damaged),” he wrote. “We thought it possible that this report was correct. The Führer was uneasy and wanted to know why our own force had not yet reported.

“I explained that radio silence was maintained at sea and that no message could be expected until our own ships returned to port.”

Vice-Admiral Theodore Krancke, naval liaison officer at Hitler’s command headquarters in 1942-43, was caught in the middle of an uncomfortable situation when a British news agency reported details of a sea battle hours before Hitler’s admirals reported them. [Wikimedia]

Nevertheless, Krancke asked operations staff to request the result of the action by a short radio signal—a “J” if the task had turned out successfully. He was later informed that the Commander in Chief, Navy Yard, had refused to request ships at sea to emit radio signals.

For reasons unknown, the rendezvous had been delayed by three hours. It may have been the result of damage to a cruiser, a breakdown on a destroyer, by heavy seas or by weather.

“In any case, the Führer demanded that any report be passed on to him the moment it came in. He still hoped it might be possible to issue an announcement of the destruction of an enemy convoy this evening or on the morning of Jan. 1. Since so far there had been no reports that enemy cruisers or similar vessels had taken part in the action, the Führer and I remained very optimistic.”

Krancke called the Naval Staff and Group North every half hour during New Year’s Eve and into the early morning of New Year’s Day 1943, asking for news. There was none.

“The Führer too sent several times to inquire whether I had any news. At 04:15, shortly before the Führer went to bed, I visited him and informed him that I would submit incoming messages immediately, so that he would have them the moment he woke.

“The Führer was very uneasy.”

At 9:15 a.m. on Jan. 1, Kranke was told the heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper had passed the outer point at their base in Kåfjord, Norway, at 2:40 a.m. He passed the news along to Hitler when he awoke at 10:30. A teletype report was expected soon.

By noon there was still no report, so Krancke again pointed out to naval staff the urgency of the situation. He was told the telephone connection was damaged.

“I informed the Führer accordingly,” he wrote. “He said it was an impudence that he as Supreme Commander had not received any news 24 hours after the action, and that the British had already given a report on the previous evening.

“In a very excited state he ordered me to send a radio message demanding a report from the naval forces. I conveyed this order to Wangenheim (Commander Hubert von Wangenheim, liaison officer at Führer headquarters).

“Then followed further remarks from the Führer, who was very excited. He spoke of the uselessness of the big ships, of lack naval officers and so on. I had to give up any attempt to explain or protest. He even stated that we dare to attack merchant vessels only if they do not answer our fire.”

Through the afternoon, Krancke’s attempts to gather further information were futile. By 5 p.m., Hitler had summoned Krancke and was asking for more news.

“He then walked up and down the room in great excitement. He stated that it was an unheard-of impudence not to inform him, that such behavior and the entire action showed that the ships were utterly useless, that they were nothing but a breeding ground for revolution, idly lying about and lacking any desire to get into action.

“This meant the passing of the high seas fleet, he stated, adding that it was now his irrevocable decision to do away with these useless ships. He would put the good personnel, the good weapons and the armour-plating to better user. ‘Inform the Grand Admiral of this immediately.’

“I tried to point out quietly that after all we must wait for the report, but he would not let me get a word in and dismissed me. I then informed the Grand Admiral.”

At 7:25 p.m., Krancke got the report he was looking for, though it did not contain the news he had hoped it would. Allied intelligence described the document as “not a cheerful text.”

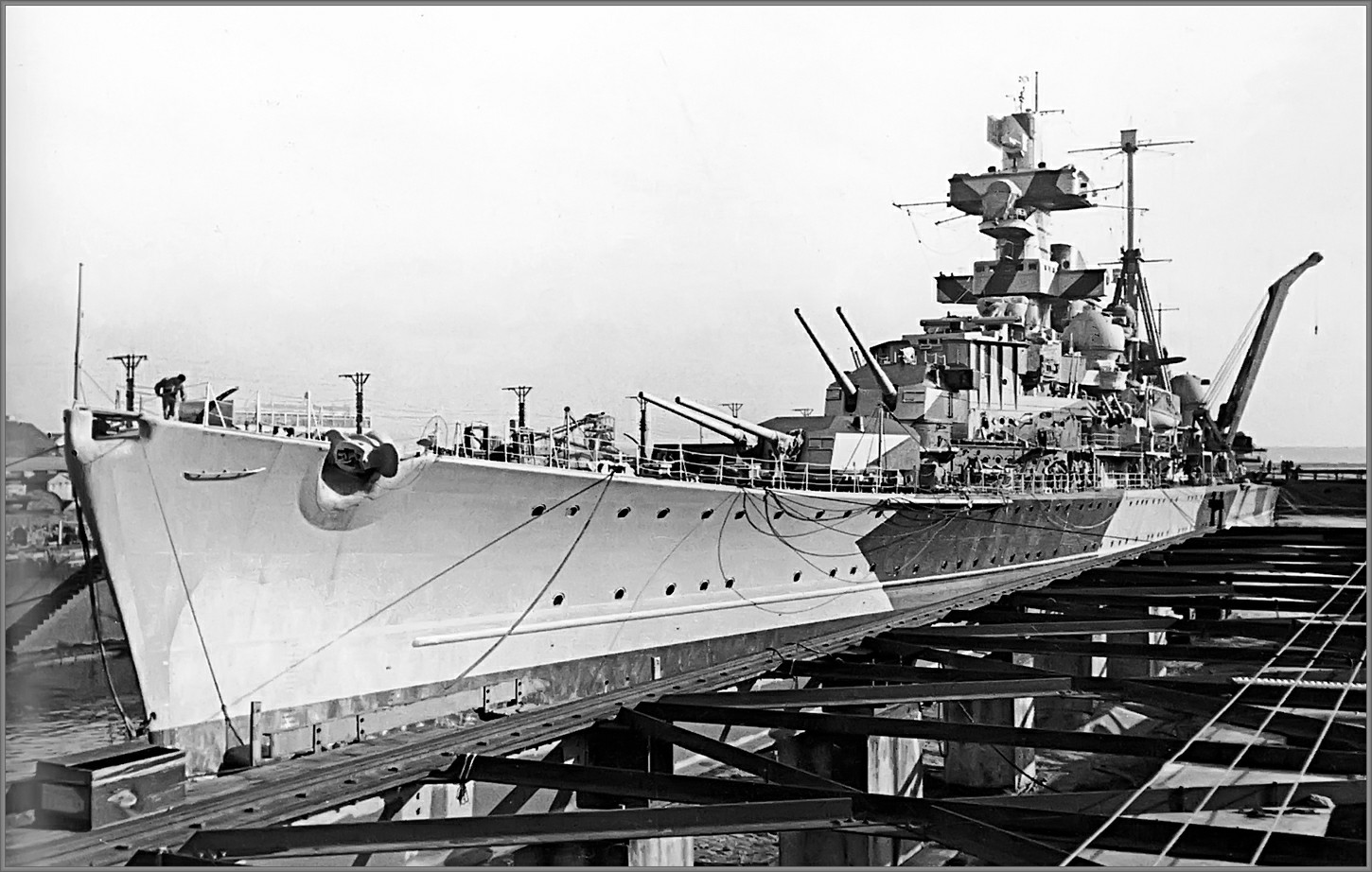

“It became known in the course of the day that our forces had been unable to penetrate the defensive screen of the enemy,” it said. “While attacking the convoy from the northwest, Hipper had been engaged by the enemy’s defence forces for a protracted period. She had been able to damage three to four destroyers.

“However, she ran from a low visibility sector into the gun range of an enemy cruiser. She was surprised and received action. Boiler from ‘4’ was…out of action for some time due to flooding. Her speed was thereby cut.”

The German heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper in Brest in 1941. The ship was scuttled at its moorings in Kiel, Germany, in 1945 after a Royal Air Force bombing raid. [Wikimedia]

In his book Arctic Convoys: 1941-1945, Richard Woodman said the encounter took place in the middle of the Arctic night. Both sides were scattered and unsure of the positions of the rest of their own ships, much less their opponent’s.

“The battle became a rather confused affair and sometimes it was not clear who was firing on whom or how many ships were engaged,” wrote Woodman.

After sinking the crippled British minesweeper Bramble, the German destroyers Friedrich Eckholdt and Richard Beitzen mistook HMS Sheffield, a Barents Sea-based cruiser called in for the action, for Admiral Hipper.

The two German ships attempted to form up with the British ships, thinking they were their own. Sheffield opened fire and Friedrich Eckholdt broke in two, sinking with all hands.

“Commanding Admiral, Cruisers gave order to break off the action and retire,” the German report said. “Enemy units which tried to maintain contact were fought off by gunfire.”

All the convoy’s merchant ships reached the USSR undamaged.

Hitler was incensed and called an evening conference.

“There was another outburst of anger with special reference to the fact that the action had not been fought out to the finish,” Kranke wrote. “This, the Führer said, was typical of German Ships, just the opposite of the British who, true to their tradition, fought to the bitter end. He would like to see an army unit behave like that. Such army commanders would be snuffed out.

“The whole thing spelt the end of the German high seas fleet, he declared. I was to inform the Grand Admiral immediately that he was to come to the Führer at once, so that he could be informed personally of this irrevocable decision.”

Raeder arrived at Hitler’s headquarters on Jan. 4, listened to his boss rant, and was then dispatched to write a report defending the navy’s performance. Raeder did so, to no avail, and subsequently tendered his resignation.

“Of the three branches of the armed forces, the navy has had the hardest struggle during this war,” he told his staff in a parting speech, blaming a shortage of ships, lack of a naval air force and disparate, self-serving leadership for the navy’s woes.

The German battleship Bismarck and its sister ship Tirpitz were the largest battleships ever built by any European power. The warship’s crew scuttled Bismarck in May 1941 after the vessel suffered catastrophic damage during a bloody battle with British torpedo bombers and Royal Navy ships. The wreck was located by explorer Robert Ballard in June 1989. [Wikimedia]

“I am certain that the navy must and will contribute largely to the successful outcome of the war, for without the success of the navy there can be no final victory.”

Raeder would be proven at least partially right. The high-seas fleet was never fully restored. Dönitz would go on to succeed Hitler as head of state and order the surrender of Nazi Germany in May 1945.

Advertisement