The Spanish Civil War, which had broken out July 17-18, 1936, had drawn to a bitter end. What followed was four decades of authoritarian rule, which ended in 1975 with Franco’s death marking the restoration of democratic values.

During the war years, however, approximately 1,600 Canadians, alongside other foreign combatants of the International Brigades, fought for the Republican cause. Their stories and struggles have been highlighted in journalist and historian Michael Petrou’s Renegades: Canadians in the Spanish Civil War.

First printed in 2008, the book is one of very few publications on what remains a little-discussed topic. Petrou, who is also the Canadian War Museum’s historian of veterans’ experience, spoke to Legion Magazine about the Canadian contingent.

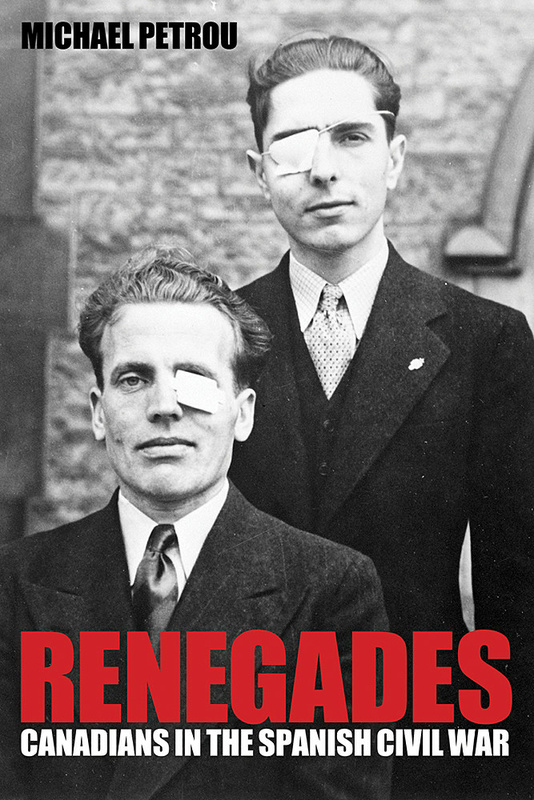

Journalist and historian Michael Petrou tells the story of the 1,681 Canadians who, between 1936 and 1939, defied Canadian law to fight fascism in the Spanish Civil war, in his 2008 book, Renegades: Canadians in the Spanish Civil War. [Michael Petrou]

Canada as a country was never officially involved in the Spanish Civil War. The federal government opposed its citizens volunteering, so those individuals who joined—and the 400 who later died—did so because they believed in the cause.

These volunteers were often poor and marginalized people, many of whom were immigrants and typically workers rather than the romanticized notion of being intellectuals. Most were also communists, although there’s nuance to that fact.

When you delve into the archives, which were held by the U.S.S.R. and Russia for many years, a theme emerges that Communist authorities grew frustrated by the supposed anarchist tendencies of Canadians. They weren’t good party members despite being communists on paper. It may be more accurate to call them anti-fascist. Certainly, there were hardcore Stalinists, but many of them were not.

Spain became a screen for people to project their dreams and ideologies. Few had a connection to Spain as a country, instead seeing it as a gathering storm of fascism being met with armed force by communists, democrats, liberals and anti-fascists.

For some Canadians, it seemed like a proxy war for their own struggles back home as relief camp workers [in the Great Depression], as downtrodden people forced to live in hobo jungles beside railway yards. For Canadian immigrants, in particular, many of whom had escaped civil wars and revolutions that had pitted left against right in their old homelands, it was a new chance to take up the fight once more.

About Canadian surgeon Norman Bethune

Bethune is a fascinating character who, like everyone, has nuances and layers. The bottom line is there aren’t a whole lot of flawless heroes. Bethune, for one, was an egoist and, by all accounts, was difficult to work with. But he was also very brave.

He came to Spain and established his innovative mobile blood transfusion unit that brought the blood closer to the front lines, later shuttling refugees in the southeast of Spain amid fascist advances. Despite this, he was eventually pressured to leave the country shortly after coming under suspicion for being a spy or fifth columnist.

I tried to untangle the precise reasons for his departure in one of my book chapters. Part of it was to do with one of the women he was romantically involved with who likewise came under suspicion. The accusations turned out to be false, and Bethune even tried [unsuccessfully] to enlist with the International Brigades in his late 40s.

Bethune is probably most famous for his work in China [during the Second Sino-Japanese War, where he died from blood poisoning on Nov. 12, 1939]. But Spain mattered deeply to him. In one letter, he dubbed the country a “scar on my heart.”

About the Canadians’ wartime experience

The majority of people joined a Communist-run organization in Canada that could arrange passage to France. The volunteers then travelled south and climbed over the Pyrenees at night. Always a treacherous journey, many Canadians were not properly equipped and struggled up, but reaching the other side as the sun rose became a special moment that took on symbolic value for the adventure ahead.

Some immigrant Canadians joined units affiliated with their homelands, while other Canadians joined the [U.S.] Abraham Lincoln and George Washington battalions, first fighting with them at the Battle of Jarama during February 1937, followed by the Battle of Brunete that summer—sustaining considerable losses.

Due to the casualty rates, the two American units merged [to maintain the Lincoln Battalion]. Subsequently, the Canadian Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion was formed.

Canadians fought and died alongside their American comrades and continued to within the Mac-Paps. Of course, there was a now-familiar culture clash between the two, especially as many Canadians were older miners and lumberjacks, while the U.S. ranks had several New York university students.

The Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion first saw action at the [October 1937] Battle of Fuentes de Ebro, which became a debacle. Some of the worst casualties, however, were incurred a little later during the [Republican] retreats [of March-April 1938].

The Canadians then participated in the last gamble, the Ebro assault in the summer of 1938, where advances were made until they were reversed. [The International Brigades were pulled from the front shortly thereafter, but the Spanish Civil War continued into the spring of 1939.]

About remembrance in Canada

The story of Canadian volunteers returning home is not necessarily consistent. You occasionally hear that none were allowed to serve in the Second World War. That’s not true—several did. But they were surveilled by the RCMP, some over decades.

It’s fair to say that they weren’t embraced by the wider public and were quick to fade into the margins. They didn’t receive the same commemorative recognition that their American and British colleagues had until relatively recently when the Spanish Civil War monument was unveiled near the Ottawa River in [October] 2001.

American volunteer George Watt once suggested that, “sometimes, lost causes are worthwhile.” Similarly, I remember one Canadian volunteer saying that although he lost his own cause, he eventually made up for it during the Second World War.

That narrative, that idea that the Spanish Civil War was almost a dress rehearsal for a larger clash with fascism over the subsequent years, has some truth in it. It’s not a very popular take, of course, because it forces us to acknowledge that democracies had chosen to appease fascism while the likes of factory workers and lumberjacks, freight train drivers, miners and more, instead had the moral clarify to confront it.

This abridged interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.Advertisement