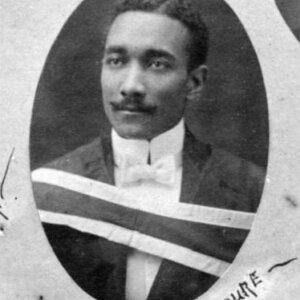

Clement Courtenay Ligoure, the first registered Black person to practice medicine in Nova Scotia. [Wikimedia]

Few, of course, would deny it’s a story that deserves to be highlighted. To unearth forgotten or largely unknown aspects, however, is a far greater challenge. Despite this, historian and Halifax disaster expert Joel Zemel has achieved precisely that.

The author’s latest publication, Dr. Clement Courtenay Ligoure, Publishing, Social Advocacy and the 1917 Halifax Disaster, explores the less discussed but equally impressive story of Nova Scotia’s first legally practising Black doctor, who faced unprecedented human destruction with unprecedented humanity. In the hours, days and weeks following the calamity, Ligoure treated hundreds of injured victims without charging a cent.

His tale is a tragic one, as Zemel explained in a Legion Magazine exclusive.

On the motivation for writing the book

I had been working as a freelancer for City News around the time a local campaign was underway to preserve Dr. Clement Ligoure’s former residence on [Halifax’s] North Street. The building was successfully registered a heritage property, which I wanted to write about. I thus started conducting research into Ligoure himself.

Unfortunately, I soon found that there weren’t many places to go for information. There was general knowledge about him originating from Trinidad and what he broadly did during the explosion. Yet there was little else until I started digging deeper; for example, unearthing his death notice and, days later, an article in a Trinidadian newspaper. That essentially opened the gates for my own research.

On Ligoure before the disaster

Ligoure came to North America because he wanted to become a doctor. He first settled in New York and ultimately attended Queen’s University in Kington, Ont., graduating in 1916 before a ban on Black medical students was implemented for decades. It was while studying that the one confirmed picture of him was taken.

Ligoure had received a commission to join a Trinidad battalion when he learned there was a problem with his medical application to practice medicine in Nova Scotia. Why, exactly, he had chosen to practice medicine there is still unknown.

The matter turned out to be a clerical error, but in the meantime, he declined the commission as he hadn’t received his [provincial] medical licence by that stage.

Months later, having fixed the issue, Ligoure tried to become the medical officer for the No. 2 Construction Battalion [a mostly Black Canadian unit]. Led by white officers, Canadian military authorities didn’t want a Black man to have that level of command, to have that particular position in the battalion—it was that simple.

Ligoure instead received a supernumerary position as a recruiter and fundraiser. He did well at raising money, probably more than anyone else, believing that it could help elevate him. It did not. He was eventually let go, which left him pretty bitter.

Another role was serving as editor and publisher of the Atlantic Advocate [Nova Scotia’s first Black Canadian newspaper]. He had also opened a private practice, having been denied hospital privileges. In 1917, Ligoure moved both his entire publishing apparatus and his 15-bed practice, which he later named the Amanda Private Hospital after his mother, to North Street. That’s where fate found him.

On Ligoure bursting into action

When the explosion tore through the city, the only people at hand to help Ligoure were his aunt Bessie Waith and Dennis Nicholas, a boarder and Pullman porter. They were inundated with patients who had been turned away from the hospital [due to limited space]. Ligoure himself worked tirelessly over several days.

The explosion happened on a Thursday, and by Monday, he asked City Hall for more help [from medical staff]. He received additional personnel to deal with the deluge. Everything Ligoure did was for free, yet he received no real recognition.

On the fading away of one of Halifax’ bright lights

Ligoure went back and forth to visit his parents in Trinidad. He fell sick following his return from one of these trips, possibly with tuberculosis, but he continued to work until 1921, when he shuttered his private practice and resettled in Trinidad.

Ligoure never came back to Nova Scotia.

It was while in he was Trinidad that the family suffered a number of tragedies. His father had already died in 1919, followed by his sister-in-law dying in childbirth in 1922. His mother then died of pneumonia. Finally, while visiting his brother in Tobago, Ligoure caught malignant malaria. He passed away on May 23, 1922, at age 34.

On the importance of Ligoure’s story

Ligoure accomplished quite a lot in his short life, even if his exploits never received the recognition they deserved over the years and decades. My biggest hope is that my book one day serves as a stepping stone for additional research. As for his legacy, I don’t use the word “hero,” but his actions were heroic.

To order a copy of Dr. Clement Courtenay Ligoure, Publishing, Social Advocacy and the 1917 Halifax Disaster, contact Carrefour Atlantic Emporium at Historic Properties, 1869 Upper Water Street, Halifax, N.S., B3J 1S9 or call (902) 423-2940.

This abridged interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Advertisement