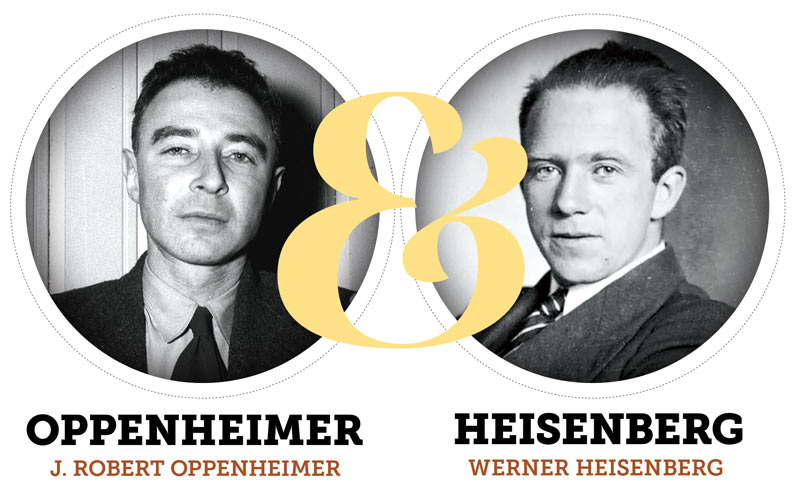

J. ROBERT OPPENHEIMER

At 5:30 a.m. on July 16, 1945, J. Robert Oppenheimer and other leading figures involved in the Manhattan Project witnessed the first nuclear detonation of a plutonium bomb in a remote corner of the Alamogordo Bombing Range, 338 kilometres south of Los Alamos, N.M.

Oppenheimer, director of the Manhattan Project’s Los Alamos Laboratory, had been appointed in the fall of 1942 to lead America’s effort to design and construct

the world’s first atomic bomb. Now, the time had come to see whether theory

could become reality.

The tower vaporized. A huge orange and yellow fireball stretched skyward and spread.

Oppenheimer wasn’t confident, betting $10 that the bomb wouldn’t work. Others present feared the explosion might ignite the atmosphere, potentially destroying New Mexico or even the entire world.

The device was mounted at the top of a 30-metre-high tower for the test—named Trinity by Oppenheimer. Precisely on time, the bomb exploded. The tower vaporized. A huge orange and yellow fireball stretched skyward and spread. Then a second, narrower column rose to form the distinctive mushroom cloud that was to be thereafter imprinted on human consciousness as the ultimate symbol of power and awesome destruction.

“We knew the world would not be the same,” Oppenheimer wrote later. “A few people laughed, a few people cried. Most people were silent. I remembered the line from Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad-Gita…‘Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.’ I suppose we all thought that, one way or another.”

‘Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.’ I suppose we all thought that, one way or another.”

—J. Robert Oppenheimer

In less than three years, Oppenheimer had led the American drive to develop an atomic weapon through to fruition. It was a stunning achievement and likely wouldn’t have been possible if he hadn’t been in charge. Oppenheimer was an exceptional theoretical physicist who had already been deeply involved in research the previous year to determine how much fissionable material—such as uranium-235 or plutonium-239—would be necessary to yield a viable weapon. This was the puzzle the Los Alamos team solved.

Originally, the Manhattan Project was intended to develop two bombs for use against Germany. The war in Europe, however, was won before the weapons were ready. Japan was then targeted. On Aug. 6, 1945, the only Manhattan Project bomb built from rare weapons-grade uranium, Little Boy, struck Hiroshima. Nagasaki was then destroyed by a plutonium bomb—Fat Boy—on August 9. The nuclear age had begun.

WERNER HEISENBERG

“I don’t believe a word of the whole thing,” Werner Heisenberg said upon hearing that the U.S. had dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Having been awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1932, Heisenberg was considered one of Germany’s leading physicists.

In 1942, Albert Speer, Reich minister of armaments and war production, had made Heisenberg the scientific head of Germany’s nuclear program. Heisenberg warned Speer that developing a functional bomb wouldn’t be possible until at least 1945 and would require a massive investment of money and other resources. Speer’s enthusiasm for the project was lukewarm. To avoid being blamed should the project fail to deliver, he never fully briefed Hitler on it.

Heisenberg was no administrator, so the German project lacked the efficient leadership and co-ordination that J. Robert Oppenheimer managed to bring to the Manhattan Project. In another 1942 meeting chaired by Speer, Heisenberg created a stir when he cited the amount of uranium-235 required to create a bomb. Various scientists and officials countered that no such weapon was possible.

Heisenberg later wrote that the “government decided that work on the reactor project must be continued, but only on a modest scale. No orders were given to build atomic bombs.”

Heisenberg’s team never produced a successful chain reaction, nor a process for enriching uranium. They failed to consider substituting plutonium for the rare uranium-235 and they based their entire project on utilizing heavy water to slow and control the fission process rather than—as Oppenheimer did—using graphite as the moderator. This last factor proved a fatal flaw.

Germany’s only heavy water source was from a plant in Vemork, Norway. On Feb. 28, 1943, a Norwegian commando raid damaged the facility’s heavy water section. Although the plant was repaired, the Allies knew what the Germans were doing there and subjected it to repeated aerial bombardment that prevented its return to full capacity.

“The whole structure of the relationship between the scientist and the state in Germany was such that although we were not 100% anxious to do it, on the other hand we were so little trusted by the state that even if we had wanted to do it, it would not have been easy to get it through,” Heisenberg wrote in 1946 while detained by the Allies.

The Germans slogged along, while the Americans—believing they were in a race—sprinted to the finish line and carried the day.

Advertisement