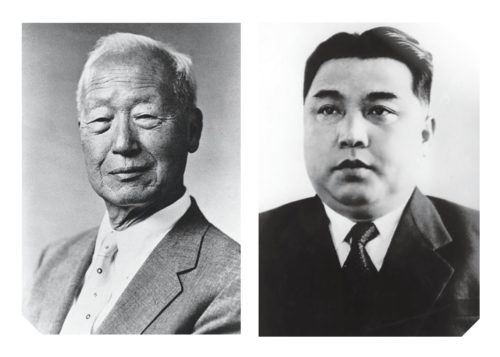

Hero: Syngman Rhee

“The new UN proposal is unacceptable to this government.…We can no longer survive a stalemate of division.”

—Syngman Rhee on June 6, 1953, stating his opposition to peace talks between the UN, the North Korea People’s Army and the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army.

Japan’s defeat in 1945 brought an end to the Second World War and its 35-year occupation of Korea. The East Asian nation, however, was immediately divided at the 38th parallel by the Soviet Union and the United States.

In 1948, the U.S. proposed a United Nations-sponsored vote for Koreans to determine the peninsula’s future. When the Soviets rejected this, South Korea formed its own government. Syngman Rhee, then 73, was elected president by 180 of 196 national assembly votes. He had been president of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea, in exile during Japan’s colonial rule of Korea from 1919 to 1945.

A devout Christian and hardline nationalist, Rhee was stylized by America’s political and military leadership as an ardent anti-communist. In truth, he was foremost committed to Korean independence and unification. A divided Korea, he believed, could never be independent. Under Rhee’s leadership, most industries and natural resources were nationalized. Extensive land-ownership reforms provided a strong base of support from the traditionally agrarian poor. Such support proved vital as his government became increasingly unpopular among urban Koreans.

In the 1950 election, 85 per cent of South Koreans voted. Rhee’s party won just 56 seats, as opposed to 128 independent candidates. Other political parties garnered only 26 seats. This outcome clearly indicated widespread dissatisfaction with both the government and all political parties.

No sooner was the election concluded than North Korea invaded.

No sooner was the election concluded than North Korea invaded on June 25, 1950. The Republic of Korea (ROK) Army was shattered—the country saved only by military support from 15 UN countries, including Canada. American General Douglas MacArthur’s bold amphibious landing at Inchon—30 kilometres west of the capital of Seoul—rescued the situation. As ROK and UN forces closed on the 38th parallel, Rhee called for an all-out drive to liberate the north. On Oct. 7, a UN resolution calling for the peninsula’s reunification was derailed by China sending thousands of troops into the war.

“Communism is cholera and you cannot compromise with cholera,” Rhee declared in opposing the U.S. and UN negotiations with North Korea, China and the Soviet Union to end the war.

Fighting to retain power, Rhee violently oppressed opposition and ultimately imposed martial law. On July 27, 1953, the war ended with Rhee reluctantly accepting the peace agreement. Rhee clung to the presidency until April 26, 1960, when he resigned following a week-long student revolution during which police killed 142 students. He died in exile in Hawaii on July 19, 1965.

Villain: Kim Il-Sung

“The peoples of Asia, Africa, and Latin America have common interest and are in the position to support each other in their anti-imperialist and anti-U.S. struggle.” — Kim Il-sung

During the Second World War, Kim Il-sung commanded a Soviet Army Korean contingent and attained the rank of major. In 1948, the Soviet Union installed Kim as North Korea’s first premier and the following year he became chairman of the communist Workers’ Party of Korea.

Quickly eliminating any rivals within the party, Kim became North Korea’s absolute ruler—transforming the country into an austere, militaristic and highly-regimented society based on his philosophy of self-reliance whereby the nation would develop its economy free of foreign influence. Simultaneously, Kim set his sights on reunification of Korea under a communist banner with himself as leader.

In 1950, confident that the war would be won in just three days and backed by the Soviet Union’s Josef Stalin and China’s Mao Zedong, Kim invaded South Korea.

North Korean divisions shattered South Korea’s army, but Kim was denied victory when an American-led UN force intervened. Vicious and costly fighting drove Kim’s army back almost to the Yalu River, which forms most of the border with China. When China entered the war, Kim led a renewed advance that captured Seoul in January 1951 before being forced back to the 38th parallel. Here the war continued until the July 27, 1953, armistice.

Never abandoning his ambition to conquer South Korea, by the early 1970s Kim had turned North Korea into one of the world’s most militarized societies, with a 400,000-strong army. An American analysis conducted in 1991 revealed that he had expanded the army’s strength to about 1 million even as North Korea’s economy dangerously deteriorated.

North Koreans were indoctrinated to believe their country was an oasis of wealth.

Such extensive militarization enabled Kim to impose a rigid communist state in which he was elevated to a godlike status. Clothes, rice, apartments—almost everything North Koreans received from government—were directly attributed to the “Great Leader.”

North Koreans were indoctrinated to believe their country was an oasis of wealth and stability amid a world impoverished by capitalism. With no outside media sources, few foreign visitors, and strict restraints on travel outside the country, this fantasy was easily perpetuated.

The end of the Cold War brought sharp curtailment of Soviet and Chinese aid. By 1989, North Korea’s gross domestic product had shrunk to two or three per cent even as Kim embarked on an aggressive nuclear program.

When Kim died on July 8, 1994, his eldest son Kim Jong-Il assumed power. Four years later, Kim Il-sung was declared in a revised constitution as the “eternal president of the republic.”

Advertisement