CURRIE

ARTHUR CURRIE

On Aug. 7, 1918, Lieutenant-General Arthur Currie briefed journalists on the offensive his Canadian Corps would launch at Amiens, France, in the coming early morning hours. “One was struck [by Currie’s] simplicity and his quiet confidence and certainty,” wrote one reporter. “He…knew the Canadian Corps and what it could do. It was a finely tempered weapon.”

Since being promoted to corps command 14 months earlier, Currie had honed the Canadians into a fighting unit considered by ally and enemy alike as the British army’s best shock troops. Whenever the Canadians appeared on the front, the Germans expected an attack was imminent.

Whenever the Canadians appeared on the front, the Germans expected an attack was imminent.

For this reason, the 100,000 troops, with all their equipment and supplies, had secretly moved to an area west of Amiens just days before the assault. In concert with the Australian Corps, the Canadians would spearhead a push that initiated a 100-day campaign that ultimately brought about Germany’s surrender.

Currie’s preparations for the offensive typified his thorough and innovative approach. Previously, he had identified a shortage of engineers, which required diverting infantry from fighting to tasks such as road and trench construction. In July, he had increased each division’s engineer battalion to a brigade size of more than 3,000 men.

“The surprise had been complete

and overwhelming.”—Arthur Currie

The success of the corps in the coming 100 days, wrote Currie later, “was due to the fact that they had sufficient engineers…in those closing battles [that] we did not employ the infantry in that kind of work. We trained the infantry for fighting and used them only for fighting.”

On Aug. 8, the infantry—accompanied by a large number of tanks—struck at 4:20 a.m. Rather than a long bombardment beforehand, the artillery opened fire just as the troops advanced. By the afternoon, with only one exception, “the Canadian Corps had gained all its objectives,” Currie later reported. “The surprise had been complete and overwhelming. The prisoners stated that they had no idea that an attack was impending.”

For 14 days the advance continued with the Canadians moving almost 23 kilometres and clearing 174 square kilometres of ground at a cost of nearly 12,000 casualties. “Considering the number of German Divisions [more than two dozen] engaged, and the results achieved, the casualties were very light,” noted Currie. He added that the “moral effect of the most bitter and relentless fighting…was tremendous. The Germans had at last learned and understood that they were beaten.”

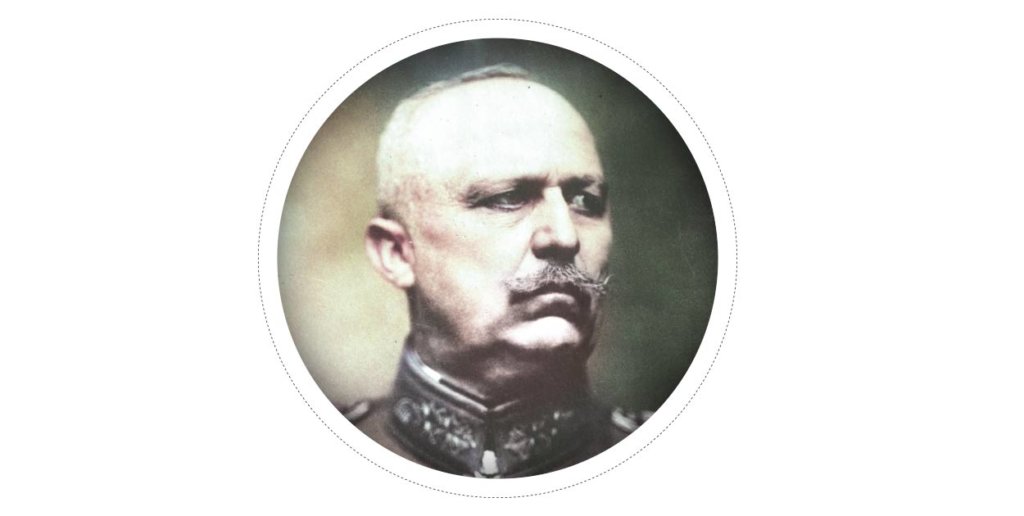

LUDENDORFF

ERICH LUDENDORFF

In the last days of July 1918, Germany’s chief strategist Erich Ludendorff watched warily for the Canadians. “The Canadian Corps, magnificently equipped and highly trained in storm tactics, may be expected to appear shortly in offensive operations,” a staff report warned.

By Aug. 2, Ludendorff was undecided on strategy. “The situation demands that on one hand we should place ourselves on the defensive, on the other that we should…go into the attack again…In our attacks…it will not be so much a question of conquering further territory as of defeating the enemy and gaining more favourable positions.”

Beginning to realize that winning the war was perhaps beyond Germany’s ability, Ludendorff sought to gain a position of decisive strength from which a suitable peace could be negotiated. While touting offensives, Ludendorff more realistically prepared to meet an Allied attack led by the Canadians. “We should wish for nothing better than to see the enemy launch an offensive, which can but hasten the disintegration of his forces,” he blustered.

Ludendorff’s general staff had no viable defensive tactic for the tanks.

Ludendorff’s problem, however, was that he had no idea where the offensive would occur. The Amiens sector was part of German Second Army’s front and Ludendorff was confident that his strength there was sufficient to meet any threat. But he only expected local attacks there, and to defeat them shifted additional artillery to this sector.

Ludendorff had also reorganized the German defensive systems along most of the Western Front so that an initial area of outposts was supported from behind by the main firepower. A major concern, though, was how German troops had been overwhelmed by Allied tanks in recent fighting. Ludendorff’s general staff had no viable defensive tactic for the tanks. Their primary instruction to infantry was “to keep their heads,” let the tanks pass and focus on “the repulse of the enemy infantry.”

“‘Everything is

lost’ was the cry.”—German officer

On Aug. 8, the Canadian Corps attacked and the Germans reeled back. “A true tank panic had seized on everything,” one German officer wrote. “Where any dark shapes moved, men saw the black monster. ‘Everything is lost’ was the cry.”

Shaken, Ludendorff noted that “whole bodies of men had surrendered to single troopers.” Aug. 8, he admitted, “was the black day of…the German Army in the…war.” Later, he added, “We have reached the limits of our capacity. The war must be terminated.”

Advertisement