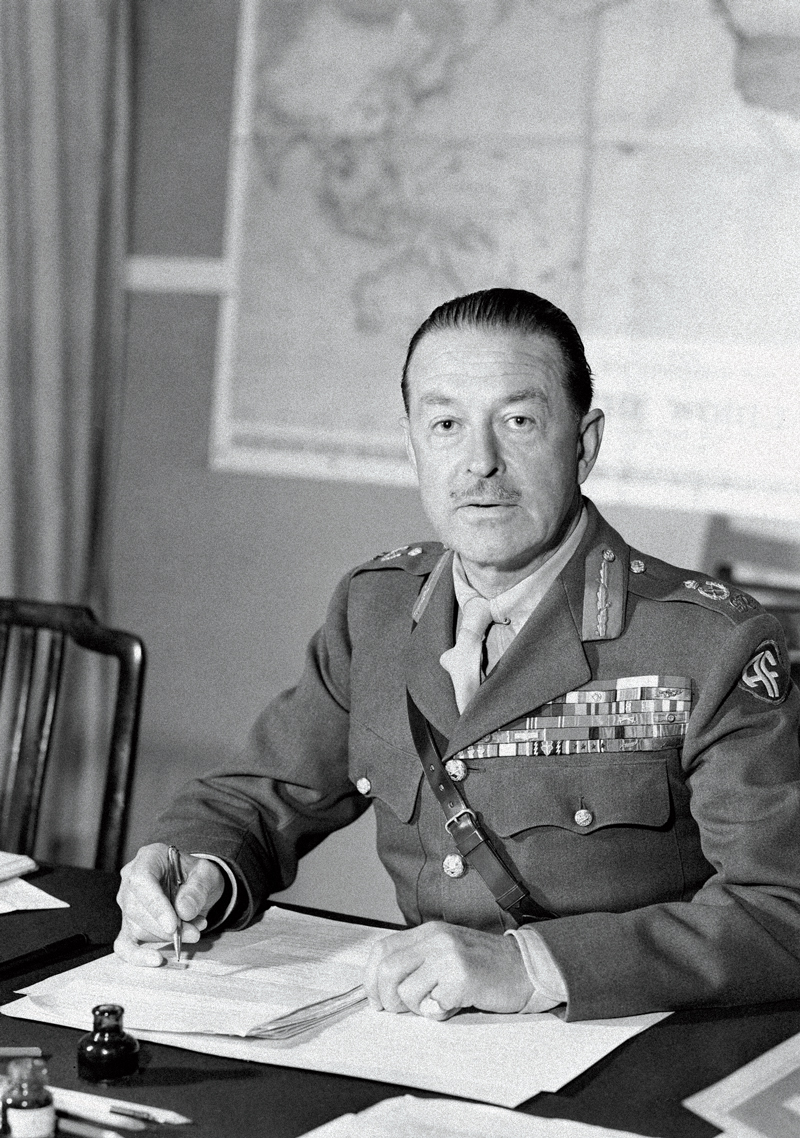

Harold Alexander

Two supreme commanders sparred for victory in Italy

“No other troops in the world but German paratroops could have stood up to such an ordeal and then gone on fighting with such ferocity.”—Harold Alexander

In September 1943, British General Harold Alexander’s 18th Army Group—having conquered Sicily—invaded mainland Italy. The stated intention was to defeat Italy but, more importantly, Alexander was to prevent German forces from reinforcing the Russian front or strengthening defences on the French coast.

Alexander had dedicated his life to being a professional soldier, entering Royal Military Academy Sandhurst when he was 19. By 1943, the 52-year-old had earned a Military Cross and Distinguished Service Cross in the First World War, defended British Empire interests in the interwar years, fought at Dunkirk, served in Burma against the Japanese, and played a pivotal role in defeating German and Italian forces in North Africa through to their surrender in Tunisia.

Alexander hoped to take Rome in a rapid pincer advance.

Along with the British Eighth Army under General Bernard Montgomery crossing the Strait of Messina and the U.S. Fifth Army under General Mark Clark landing at Salerno, Alexander hoped to take Rome in a rapid pincer advance up both Italian coasts.

Instead, the Allies slammed head-on into German Field Marshal Albert Kesselring’s 10th Army. The ensuing campaign was a gruelling, protracted and bloody slog across rugged terrain. Rivers crisscrossing the line of advance provided ideal defensive positions that had to each be taken in turn. Asone obstacle fell, Kesselring masterfully pulled his troops back to the next feature—denying the Allies a decisive victory.

Alexander was dogged by a perpetual shortage of manpower and resources. Bogged down before Monte Cassino in early 1944, he scrapped the pincer effort and concentrated both armies on the western coast in order to mount a breakthrough to Rome in May.

For Operation Diadem, Alexander believed the Allies required a three-to-one infantry superiority, only to learn the ratio could be no more than one-and-a-quarter times in his favour.

Still, by early June the Allies had shattered German defences and were poised to take Rome. Alexander, however, no longer coveted the Eternal City. He sought instead to cut off Kesselring’s retreating force and destroy it. Such a victory could decide the Italian campaign. The plan was for Clark’s army to trap the Germans by blocking Highway 6 between Valmontone and the Alban Hills. Instead, taking advantage of Alexander’s conciliatory nature—often considered his major failing—Clark turned prematurely north for the distinction of liberating Rome. The Germans escaped to fight on. No decisive victories followed until the German surrender in Italy on April 29, 1945. War over, Alexander served as Canada’s governor general from April 12, 1946, to Feb. 28, 1952.

Albert Kesselring

Albert Kesselring [wikimedia]

“I was always a soldier heart and soul.”—Albert Kesselring

When the Allies invaded Italy in early September 1943, the German response remained undecided with two field marshals—Albert Kesselring in the south and Erwin Rommel in the north—charged with its defence. After Italy’s Sept. 8 surrender, Rommel advocated withdrawing to protect Milan’s industrial heartland while Kesselring—having freshly evacuated his troops from Sicily—argued the Allies could be halted in the south or drawn into an attritional war by standing on successive defensive lines. Kesselring’s strategy gained sway after the U.S. Fifth Army suffered heavy losses during the Salerno landings.

“I wanted to be a soldier. I was set on it and…I can say that I was always a soldier heart and soul,” Kesselring later wrote.

He joined the army at 18 in 1904. He served on the Western Front for two years before his appointment to the general staff. In the 1930s, under Hermann Göring’s

patronage, Kesselring became the Luftwaffe’s chief of air staff. Promoted to field marshal in 1940, he commanded air units during the Battle of Britain and the Siege of Malta before being tasked with defending Sicily and then commanding the 10th Army in Italy.

Nicknamed “Smiling Albert,” Kesselring exuded a cheerful, seemingly endless confidence that exacerbated a frequent inability to accept unpleasant realities.

In May 1944, Kesselring almost fatally refused to accept that Monte Cassino and the Hitler Line—soon shattered by I Canadian Corps—could fall. Retreating to the Melfa River, he imagined holding that precarious line until winter precluded further operations. This delusion was quickly shattered by the unceasing Canadian advance that put his entire army at risk of being cut off—a fate only averted when U.S. General Mark Clark allowed its escape while he liberated Rome instead.

Ever agile, Kesselring pulled his forces north in a rapid withdrawal to the Gothic Line—anchored on the Apennine dogleg across the breadth of Italy. Here he frustrated one Allied offensive after another—save for the Canadian-led Eighth Army breakthrough on the Adriatic coast.

Kesselring exuded a cheerful, seemingly endless confidence.

Seriously injured on Oct. 25, Kesselring briefly returned to Italy command in January 1945 before he was appointed Commander-in-Chief West on March 10. No miracles on the Western Front were possible. War lost, Kesselring was tried and sentenced to death for war crimes against Italian civilians murdered in retaliation for partisan operations. In October 1952, soon after his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, Kesselring was released for health reasons. He died on July 16, 1960.

Advertisement