Throughout World War II, the Royal Canadian Navy was called upon to participate in virtually every phase of the war at sea. The Battle of the Atlantic was the longest continuous battle of that war. It began in September 1939 and ended in May 1945. The RCN’s main role was to enable as many merchant ships as possible to reach their destinations, which was achieved by forming merchant ships into convoys protected by warships. We are pleased to present the following excerpt from the recently released book No Higher Purpose: The Official Operational History of the Royal Canadian Navy in the Second World War, 1939-1943, Volume II, Part 1.

Produced by Vanwell Publishing Limited and the Department of National Defence, the book, which is also available in French, was written by historians W.A.B. Douglas, Roger Sarty and Michael Whitby with help from Robert H. Caldwell, William Johnston and William G.P. Rawling. It is the result of more than 15 years of research in Canada, Germany and Great Britain, and its long-awaited release coincides with the 60th anniversary of the Battle of the Atlantic.

No Higher Purpose chronicles the rapid expansion and transformation of the RCN between 1939 and 1943. It sells for $60, not including tax and shipping, and is available at most bookstores or by contacting Vanwell Publishing at 1-800-661-6136. The e-mail address is: sales@vanwell.com. Part 2 of Volume II is expected to be published in 2004. It is titled A Blue Water Navy: The Official Operational History of the Royal Canadian Navy in the Second World War.

* * *

|

|

Top: Sailors on board a Canadian river-class destroyer practice depth-charge drill in October 1941. Middle: Canadian corvettes Orillia (foreground) and Cobalt arrive in St. John’s, Nfld., in May 1941. The two ships became part of the Newfoundland Escort Force. Bottom: Longshoremen load cases of TNT in the hold of an unidentified merchant ship at Halifax in November 1941 for transport to the United Kingdom. |

Disasters seldom, if ever, have a single cause. They are the product of many circumstances and events, interwoven, as it seems in retrospect, with a relentless and increasing tightness, much as one carefully stacks wood on paper and kindling, and then lights a match. The records of slow convoy SC 42, which sailed from Sydney, N.S., on the morning of Aug. 30, 1941, convey precisely that sense of impending doom, unfavourable turn succeeding unfavourable turn, always at the worst possible moments.

SC 42 was only the second of the slow convoys to sail alone, without the benefit of the double escort provided in the combined SC/HX convoys. (HX refers to the fast convoys from Halifax and later New York to the United Kingdom.) Moreover, because it sailed so early in the reorganized cycle, there had not yet been time to balance the numbers of merchant vessels among the HX convoys and the now more numerous SC ones to produce the moderately sized convoys that the new schedules were designed to achieve. As a result, SC 42 was large. Sixty-two merchant ships departed from Sydney and five more joined from Wabana, the anchorage in Conception Bay near St. John’s where ships loaded in Newfoundland assembled. These numbers created an impossibly long perimeter for the standard western-ocean escort group of only four warships to protect.

The senior ship, Skeena, was arguably as experienced and professional a destroyer as any then on the North Atlantic run. Lieutenant-Commander J.C. Hibbard, RCN, affectionately known in the fleet as “Jumpin’ Jimmy” on account of his excitability on the bridge, had assumed command in April 1940, shortly before Skeena crossed to Britain. As in all the Canadian river-class destroyers, there was still a large proportion of regulars on board, including some of the RCN’s most promising young officers. Of the three corvettes that made up the rest of the escort, Orillia and Alberni had been among the original seven vessels in Commander J.D. Prentice’s work-up program at Halifax in the early spring, before they rushed into operations as charter members of the Newfoundland Escort Force, NEF, in June. Their captains, Lieutenant W.E.S. Briggs and Lieutenant-Commander G.O. Baugh, were two of the more capable Royal Canadian Naval Reserve commanding officers. Still, their ships, although veterans in the Canadian sense of the word, had scarcely three months time on operations and were manned by Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve personnel with little previous experience. The third corvette, Kenogami (Lieutenant-Commander R. “Cowboy” Jackson, RCNVR), had spent just over six weeks at Halifax fitting-out and working-up, after commissioning on June 29.

The arrangements for SC 42 seem at first sight to have been a recipe for disaster. In fact, they were built on success. The reorganization of the convoys, essential to increase the carrying power of the merchant fleet’s best ships, also ensured that American assistance, only days away and expected to be on a considerably larger scale than proved to be the case, could immediately be deployed to the best effect. No transatlantic convoy, moreover, had come under sustained attack in over two months, the last being HX 133 in late June. That convoy, too, had been lightly escorted, but it had been possible to make a timely reinforcement with escorts from nearby convoys not under direct threat, thanks to decrypts of German radio traffic, in combination with the well-developed system of HF/DF (High Frequency Direction Finding) stations that now ringed the North Atlantic.

Despite the fact that the daily settings for Enigma machines had expired at the end of July, Bletchley Park was still in a position to provide useful information. (Enigma was the German cipher machine adopted by the German navy in 1926. The output, when deciphered, was known by the Allies as Ultra. Bletchley Park was the site of the British government’s code and cipher school. From 1942 on, it was the government’s communications headquarters.)

The decryption staff had amassed enough information about German naval signals and encryption procedures to narrow the nearly infinite possible settings to a number that could be tested within days rather than weeks or months. Electrical-mechanical “bombes,” whose wiring duplicated that of the Enigma machines, rapidly ran settings to select the one that produced a meaningful text. It took Bletchley “about three days to solve the settings for the first of a pair of days of August traffic, and under 24 hours for those of the second day,” which gave “an average delay of 50 hours.” That was normally good enough to divert convoys clear of danger….

There was, of course, risk, but there was the need to accept risk in order to assure continued success. Ironically, the threat to SC 42 developed in part because of the very effectiveness of British defence measures. The Admiralty had routed the convoy to the north, towards Greenland, to take it over the top of a large group of U-boats, Markgraf, southwest of Iceland. Not only had these boats–deployed in compact patrol lines–failed to locate any shipping, but maritime patrol aircraft based in Iceland had damaged two of them, enabling surface vessels to destroy another and capture a fourth. On Sept. 6, therefore, the commander of the German U-boat service ordered 14 boats to take up widely scattered patrol areas from midway between Iceland and Greenland down to Cape Farewell and some 400 miles further south, thus covering in a very loose fashion the central and northern routes between Newfoundland and Iceland. By a stroke of bad luck, and it was nothing more, Bletchley Park could not decrypt the orders for this movement west until Sept. 8, when it became clear, too late, that SC 42 was standing into danger.

Even so, the Admiralty was able to divert most convoys to the south of this large area. One, the slow ON 12, was already west of Iceland and could remain on the northern route in the high latitudes. (ON was the abbreviation for UK to North America convoys.) SC 42, however, had run into an easterly gale on Sept. 3 that raged on until the morning of Sept. 7. Stiff headwinds and heavy seas reduced its speed to as little as 2.56 knots, so that by Sept. 8 it was approaching Cape Farewell, 72 hours behind schedule instead of being, as it should have been, clear to the north of the new U-boat disposition. And the escorts, after the prolonged struggle to maintain their heading and keep contact with the merchant vessels in the teeth of the gale, were too low on fuel for the extra run of several hundred miles necessary for a diversion to the south. Thus committed to the Greenland route, they were heading straight for the northwestern end of the new U-boat deployment.

On the evening of Sept. 8 the Admiralty diverted SC 42 straight north towards Cape Farewell hoping that, by hugging the eastern coast of Greenland, it could make an end run around the most westerly of the submarines, and then cut east again over top of the German patrol areas. It so happened that the fast westbound convoy ON 13 was approaching the waters south of Iceland, roughly along the latitude of 58’30” North, with an escort of five destroyers, four corvettes, and two anti-submarine trawlers. (This in contrast to the four escorts with the much larger SC 42 was vivid evidence of the difference in scale of the defences provided in the eastern Atlantic as compared to the western ocean.) British command authorities ordered the destroyers, HMS Douglas (Senior Officer Escort), Leamington, Veteran, Skate, and Saladin to detach for Iceland and refuel so they would be available as reinforcements. To provide a further reserve, instead of sending a Newfoundland group out from Iceland, to take over the escort of ON 13 for the western part of its voyage, routing authorities in the UK diverted the convoy southward and dispersed it when the corvettes and trawlers remaining from the Western Approaches escort had to return to port.

A more modest but unconventional reinforcement was also on its way. In August, while commanding Chambly and as Senior Officer corvettes, Prentice had returned from the nearly constant convoy operations undertaken since June to take up local defence duties and to train the most recently commissioned corvettes before they started ocean escort. (The pressure of operations and unexpected breakdowns of ships had again overtaken the scheme. Chambly had to sail for a patrol to the Strait of Belle Isle until late in August, and then only one of the newly arrived corvettes, Moose Jaw, could be assigned to Prentice’s group.) Thus, on Sept. 4, while struggling to put together an exercise program with the limited facilities available at St John’s, Prentice noticed in the Admiralty’s daily signal of estimated U-boat positions the initial movement of a large number of U-boats west of Iceland. He persuaded Commodore L.W. Murray and Captain E.B.K. Stevens that instead of carrying on with their local training program, Chambly and Moose Jaw should “top up with fuel tomorrow…and then sail to work up together on a cruise on convoy routes.”

Prentice was seizing the opportunity to realize his ambition of organizing a special submarine hunting group, free of responsibility for escort, and ready to support any threatened convoy by sweeping well ahead to catch U-boats that were moving up on the surface to attacking positions. It was a bold, almost reckless initiative. Although Moose Jaw was one of the very few corvettes commanded by a regular force officer, Lieutenant F.E. Grubb, RCN, most of his inexperienced crew, missing several key specialist personnel, “was seasick for the first four days at sea, some of them being quite incapable of carrying out their duties.”

As luck would have it, after days of thick weather, when SC 42 passed Cape Farewell and proceeded up the Greenland coast, visibility was excellent, and nothing could persuade ships in the convoy to stop making smoke, which the convoy commodore later reported “was (doubtless) visible for at least 30 miles.” At about daybreak on Sept. 9, U-85, under the command of Oberleutnant-zur-See Greger and westernmost of the Markgraf group, sighted “smoke plumes” and, after positioning himself ahead of SC 42, a manoeuvre that took several hours, made a submerged daylight attack, firing four torpedoes from close range into the merchant ships at the rear. One torpedo failed to leave the tube, and the other three missed. Then, shortly after 1000 local time, Greger fired from his stern tube at the transport ship Jedmoor, which was straggling behind the convoy. “Just at this moment,” Greger recorded, “the steamer turned towards me. This shot therefore also missed. All of the shots were made using a target speed of eight knots. However, I later established that the convoy was proceeding at six knots. What a dismal start…. It must be because it is our 13th day at sea!”

A sweep by the escorts in response to Jedmoor’s report of torpedo tracks and a periscope turned up nothing, but the commander-in-chief of Western Approaches, informed by U-boat signals that emanated from the northern route between Iceland and Greenland, sailed reinforcements from Iceland for both SC 42 and ON 12, and Murray ordered Chambly and Moose Jaw to make for SC 42. It would take Prentice’s little group some 24 hours, and the ships coming from Iceland over 36 hours, to reach SC 42, and since excellent radio transmission conditions ensured that U-85’s contact report got through immediately to the other boats of Markgraf and to the commander of the German U-boat service, a full-scale attack was well under way long before the arrival of reinforcements. At least three boats, on receiving Greger’s sighting report, had already turned to intercept the convoy and thanks to the moderate seas, three of them, U-81, U-432, and U-652, had joined U-85 by the early hours of darkness that same day.

At 2130, Oberleutnant-zur-See Schultze’s U-432, remaining submerged because of the bright moonlight, fired four torpedoes and drew first blood. At least two hit Muneric, loaded with iron ore at the rear of the port wing column, and the ship sank like a stone with all hands. In the confusion of explosions, emergency rockets, and starshell, the escorts did not at first realize Muneric had disappeared. Schultze, hearing the sounds of pursuit–probably Kenogami which had already been “very much a nuisance” during his approach–laid low. Greger in U-85, closing on the surface ahead of the port wing column, was shaken to see starshell bursting in his direction, probably from Skeena crossing the van of the convoy in response to the report of the attack on Muneric. Withdrawing in the direction of the Greenland coast, he found himself under pursuit from a “destroyer.” It was actually Kenogami, which had sighted a submarine fleeing on the surface and given chase. Wanting to remain on the surface and to fire, Greger attempted weaving five degrees to each side of his course but, as he wrote in his log, “The destroyer closes rapidly, gradually turns to follow me. This is a cat and mouse game. I clear everyone off the bridge except myself.” When Kenogami opened fire at 2158, Greger took his only option, an emergency dive. Somehow, Kenogami had not been supplied with starshell and so could not indicate her position for Skeena to join. Nevertheless, U-85 did not dare to surface for nearly two more hours.

As Greger dove for cover, several merchant ships in the centre of the van reported a U-boat on the surface, probably U-81, and opened fire, causing a fourth submarine, U-652 under Oberleutnant-zur-See Fraatz, to abort its approach. A little less than two hours later, Fraatz pushed right into the convoy from the starboard quarter, selecting a tanker as his target “beyond which there are sufficient other targets for the remaining available bow tubes.” For his pains, U-652 “was fired on with 8.8-cm shells by the rear-most ship in the right-hand column, range 300 metres. Red tracer fire from a 2-cm machine-gun is being directed above the conning tower and the net cutter from my port quarter.”

The merchant ships providing this hot reception broke radio silence to report the situation. From Skeena’s bridge, Hibbard could see rockets on the starboard quarter of the convoy, and as he received the report he increased to 18 knots and steamed between columns seven and eight, right down the centre of the convoy, as it executed an emergency turn of 45 degrees to port. “Ships in columns 7 and 8 were steering various courses,” stated Hibbard, “and full speed ahead and astern had to be used on the engines to avoid collision.” Unable to fire starshell because of its blinding effect, Hibbard switched on his navigation and fighting lights and manoeuvred precariously as captains shouted sighting reports to him by megaphone. Skeena “was between columns 6 and 7 …when the U-boat was sighted. #74 (SS Southgate) called by megaphone that a submarine was on her starboard beam. At about (2354 SS Tahchee and SS Baron Pentland were hit by torpedoes; these ships were)…within about 200 yards of HMCS ‘Skeena’ on the starboard quarter.” Unable to ram with merchant ships so close, Hibbard fired starshell and dropped a pattern of depth charges on the position of the sighting. U-652 did not see Skeena, but was now coming under accurate fire from the merchant ships, and therefore crash-dived the instant it had fired two torpedoes. That Fraatz did not suspect the presence of the destroyer made Skeena’s counter attacks all the more unnerving. He counted seven charges and thought they must have been dropped by the merchant ship that had fired on him:

“There were no escorts in the close vicinity. Opened out on courses between 220 and 150. Screw noises are heard in the listening device from two vessels, rapidly turning screws, which station themselves on the port and starboard quarters and the vessel on the port quarter appears to be equipped with an asdic device….

“When I turn around course 180 the screw noises reappear. I suspect the presence of a piece of search gear, in any case I do not understand the small number of well-aimed depth charges.”

The aggressiveness of Hibbard and the merchant ship captains may have appeared chaotic and ineffective, but it kept Fraatz under for the next nine hours. Although he then pursued the convoy, he did so cautiously, eventually making two attacks that missed their targets, which in both cases appear to have been stragglers behind the main body.

At 0029 on Sept. 10, Skeena ordered Orillia to drop astern and rescue the survivors of U-652’s successful thrust into the centre of the convoy. U-432 saw the corvette falling back, and Schultze got through the resulting gap in the screen to work his way up the dark port side. Beginning at 0207, he fired four torpedoes that sank SS Stargard in the port wing column and SS Winterswijk in the second column. “Powerful explosion,” he recorded, “white-coloured explosive cloud, sinking not observed as the sky is now brightly illuminated by starshells, depth charges are being dropped and two corvettes (in fact, almost certainly Skeena and Kenogami) are closing the boat”–the large cloud probably came from Winterswijk, which was carrying a cargo of phosphates and lost 20 people from a crew of 33. While U-432 was making its escape from Skeena and Kenogami, U-81 was closing the opposite, starboard, side of the convoy. Between 0228 and 0253, Oberleutnant-zur-See Guggenberger fired five torpedoes, the last of which sank MV Sally Maersk, leading the starboard column. Accurate fire from the surrounding merchant ships drove the submarine off and Skeena, in response to their radio reports, ordered Alberni, the only escort available on the starboard side of the convoy, to make a search.

Kenogami and Alberni, under orders from Hibbard not to linger in their searches for the most recent attackers, refused to ignore survivors in the water. Not until about 0500 did they rejoin, Kenogami carrying the entire 34-man crew of Sally Maersk. SS Regin had courageously stopped, and then dropped back during U-652’s attack, to rescue Stargard’s crew. Orillia, astern of the convoy since about 0047, was fairly overwhelmed with more than 100 survivors from Tahchee, Baron Pentland, and Winterswijk. At 0425, Orillia located the still-floating hulks of Tahchee and Baron Pentland. Briggs, an experienced merchant mariner, saw possibilities for saving one or both of the vessels, and obtained permission from Hibbard to delay his return to the convoy.

The escorts had driven off all four submarines originally in contact, but a fifth, U-82 under Oberleutnant-zur-See Rollmann, had reached the scene during the night. At first deterred by the escorts’ sweeps and an emergency turn by the convoy, Rollmann was able, with the departure for rescue work of all of the warships save Skeena, to make a submerged attack on the port wing. At 0457 he loosed a salvo of two torpedoes that hit SS Empire Hudson, a brand-new freighter at the head of the second column equipped with fighter aircraft and catapult launching gear. Skeena rushed to the position, and had just “dropped depth charges on a good echo,” when the convoy commodore, at the centre of the van, signalled a periscope sighting report. Hibbard had to abandon the hunt to head off what appeared to be a new attack.

In the meantime, Briggs in Orillia remained with the hulks of Baron Pentland and Tahchee. U-82 watched these efforts from periscope depth. Rollmann did not attack because he suspected a “U-boat trap.” A plume of smoke from the hulk’s funnel as volunteers from the tanker’s and Orillia’s crews began to raise steam convinced him that the hulk was not what it seemed and might be a heavily armed vessel disguised as an easy target. At about 0940 therefore, with “ice-covered mountains of Greenland” in the “brilliant sunshine” astern, Rollmann set off in pursuit of the “few pale smoke plumes” of the main convoy. Orillia and Tahchee trailed, ever more distant from the convoy, which was now more vulnerable than ever with only three escorts. Clearly, five or six would have left the convoy in better shape when the U-boats reacted so definitely to the mere suspicion that a warship was nearby.

At 1000, Greger in U-85 was already diving ahead of the van, dodging Skeena. Like Rollmann, Greger somehow took the destroyer to be an American ship, “flying the American ensign…and banners with stars on the bridge and hull.” Through his periscope, Greger also saw an aircraft circling overhead, the first of the Iceland-based long-range Catalina flying boats to reach the convoy. The lead merchant ships, meanwhile, sighted U-85’s periscope, opened fire, and called Skeena, which swept through the area, but could not get an asdic contact. Hibbard dropped depth charges anyway, but they were so wide of the mark that Greger believed the detonations were torpedoes being fired against other parts of the convoy. Nearly two hours later, at 1142, he fired two torpedoes that hit SS Thistleglen, at the head of the ninth column, near the starboard wing of the convoy. Skeena quickly closed the stopped, stricken ship now drifting astern of the convoy, ordering Kenogami and Alberni to take up positions abreast of the destroyer for a coordinated sweep astern of the convoy.

Shortly after noon they could see merchant vessels ahead of them firing at an object in the water, soon identified as a periscope, that disappeared within 60 seconds. Skeena rushed in at 24 knots–too fast for asdic to function–and made a snap visual attack near the position of the periscope. Greger had, in fact, just fired two torpedoes into the convoy; both missed, but no one noticed them amidst the gun fire and the depth-charge explosions, and Skeena’s attack was far off target. She subsequently made asdic contact, obscured when Alberni attacked another, less certain one, but Skeena and Kenogami then regained the contact with a more deliberate approach. Kenogami helped to guide the destroyer on her attack run, and at 1305 Skeena dropped a pattern of 10 charges that brought a large air bubble, followed by smaller air bubbles and a small oil patch to the surface. None of the warships could now get an echo, and Hibbard concluded after 15 minutes that the submarine had been destroyed. U-85 had, in fact, survived, but only just:

“Six depth charges explode at close range. All manometers except for the main one are knocked out, as are the depth rudder, gyro compass repeats,

the magnetic compass, the side rudder, the engine room telegraph and all lighting. The port engine stops. The boat descends, but the dive is arrested at depth 85 (a drop of 25 metres from its previous cruising depth of 60) by trimming using the crew (to gather aft) and running one engine at 3/4 speed.”

The escorts, unable to regain contact, perhaps because of this fast plunge, resumed their stations around the convoy.

With the destruction of Thistleglen, Hibbard realized he could no longer spare Orillia, even in daylight hours. He did not want to reveal to listening U-boats the diminished state of the escort and give away Orillia’s position, so rather than making a signal by radio he flashed the recall instructions to one of the Catalinas, asking the aircraft to search out the corvette and pass the message. These instructions never reached Orillia, and in a superb feat of seamanship Briggs subsequently jury-rigged a tow to the huge, balky Tahchee, bringing the valuable tanker safely to Iceland. This was a wonderful achievement, but because it reduced the already meagre screen by 25 per cent it imperilled scores of ships for the sake of one. Briggs should have delayed his return no longer than it took to save lives, something an experienced naval officer would have known instinctively. Briggs, not surprisingly after only a few months in command, was still thinking like the merchant mariner and fine seaman that he was.

An hour and three quarters after near destruction, U-85 surfaced, but was almost immediately forced to crash-dive by a Catalina. When Greger came to the surface half an hour later the aircraft, which had lingered in the vicinity, attacked with depth charges that forced Greger to take his boat down again until after dark, when he crept away on the surface to make such repairs as were possible and head for home. Meanwhile, Guggenberger in U-81 thought the determined action against U-85 had been meant for him, even if it seemed to be poorly directed, so he aborted his submerged approach and lay low for nine hours. When he surfaced at 1500, he soon had to crash-dive as a Catalina neared, and with only one torpedo remaining he too decided to turn for home.

The Catalinas held the U-boats at bay through the afternoon and evening of Sept. 10, but more submarines were gathering for the kill. U-84, U-202, U-207, U-433, and U-501 in addition to U-82,

U-432, and U-652, were endeavouring, with fast surface runs, to gain favourable attack positions ahead of SC 42. They had to abandon the effort repeatedly as the appearance of aircraft forced them down, but Rollmann in U-82, after three crash-dives to avoid aircraft, realized that he would shortly lose any hope of contact, and therefore boldly stayed on the surface. At first on tenterhooks–there were two Catalinas on patrol in the late afternoon and early evening–his confidence grew when he realized the aircrew could not see him in the dimming light. As he closed from ahead, cloud cover frequently blacked out the moon in the vicinity of the convoy, enabling him to approach the starboard side, where he would otherwise have been silhouetted by the moonlight shining from that direction. He fired three torpedoes, and at about 2056 hit MV Bulysses, leading one of the starboard-most columns:

“the large tanker explodes, a red tongue of flame shoots vertically upwards roughly 300-400 metres, changes colour to bright yellow and lights the convoy as if it were daylight. There is the stench of fuel and I can see a tall black smoke cloud in the sky for a long time. The remains of the tanker, a section of ship roughly 30 metres in length, continues burning.”

Incredibly, 50 of the 54-man crew got away, thanks largely to the Polish freighter Wisla which, in the midst of the danger and chaos, immediately stopped to pick up the survivors. It may have been this scene that a boat newly in contact, Kapitänleutnant Ey’s U-433, witnessed. He prepared to attack the rescuers, but pulled away when a Catalina showing lights swooped close by. Skeena searched well ahead of the convoy, assuming that the submarine had retreated into the darker conditions there. But U-82 had kept close, and at 2112 fired a torpedo that hit SS Gypsum Queen at the head of the eighth column, almost precisely at the moment the ship broadcast a submarine sighting report. The countermeasures were not without effect, however, for yet a third submarine, U-84 under Kapitänleutnant Uphoff, had been closing to attack. After being “driven back by escorts several times” the U-boat fired four torpedoes at 2130–without result–and then quickly withdrew in the face of an apparent pursuit by “a destroyer.”

It was at this moment that Chambly and Moose Jaw, Prentice’s reinforcements from Newfoundland, sighted the signal rockets shooting up from the merchant vessels. They were a few miles to the northwest of the convoy, a notable navigational achievement after a six-day run in which the correction on the corvettes’ magnetic compasses had proven to be inaccurate and had had to be adjusted in mid-passage. Prentice had hoped he might catch a submarine closing from ahead of the convoy–the U-boats’ preferred tactics–and lauded the “exceptionally good navigating of my Navigating Officer, Mate A.F. Pickard, RCNR.” Chambly got a firm asdic contact, “port beam, range 700 yards,” and Prentice decided “in view of the handiness and small turning circle of a corvette” to attack at once. The target, which turned out to be U-501, and the corvette were closing rapidly “head-on, on opposite courses,” so at 2138 Prentice ordered an “early drop” of a five charge pattern.

The Port Thrower misfired and the OD (ordinary seaman) at the Port Rails, a relief for a man in hospital who had only been in the ship for a few days, failed to pull his lever when the firing gong went. This omission was instantly corrected by Sub-Lieutenant Chenoweth, RCNVR, an officer who has also just joined the ship and has never been to sea before. The result was that the first and second charges were dropped close together.

The first and second charges were heard to explode almost together and several observers counted a further three explosions, the last appearing to be of a different nature and more violent than the remainder.

Prentice believed the first two charges, dropped almost simultaneously because of Chenoweth’s quick thinking, were closest to the mark. The submariners below later agreed. While Chambly turned to make another depth-charge attack, the damaged U-boat surfaced near Moose Jaw. The boat attempted a hasty withdrawal and Moose Jaw opened fire, but an overexcited sailor in the four-inch gun’s crew jammed its mechanism. What then took place was not untypical of the close-range combat that could occur in submarine warfare. In the words of Moose Jaw’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Grubb:

“14. The next few minutes was spent in chase…. At one time four of the submarine’s crew made a determined move to the after gun. As our own gun was still jammed, no action could be taken except to increase speed and try to ram before they could fire. This I did, although the chance was small, but, fortunately, someone on the conning tower ordered them back. The .5-inch machine-guns were bearing at the time, but when the trigger was pressed, they failed to fire. A subsequent check showed no defects, so I assume that in the excitement the crew failed to cock them.

“15. I managed to go alongside the submarine, starboard side to, and called on her to surrender. To my surprise, I saw a man make a magnificent leap from the submarine’s deck into our waist (the mid-part of the corvette), and the remainder of her crew move to do likewise. Not being prepared to repel boarders at that moment, I sheered off. The submarine altered across my bows and I rammed her (a glancing blow that, fortunately, did not seriously damage the corvette)….

“16. After the impact she moved across my bows at reduced speed. The gun being cleared by that time I opened fire again. The crew jumped into the sea as soon as the first round went, and I ordered fire to be stopped. I subsequently learned that the shell had passed low enough over the conning tower to knock down the men who were standing thereon….

“18. The man who I had seen jump on board turned out to be the submarine’s commanding officer. He was badly shaken and when he was brought to me on the bridge appeared to be worried at the amount of light we were showing in order to pick up survivors.”

Chambly put an armed boarding party on the submarine in an attempt to capture it, but the Germans refused even at gunpoint to re-enter U-501, now sinking by the stern. Lieutenant E.T. Simmons, RCNVR, Chambly’s first lieutenant, courageously struggled through the hatch into the conning tower, but only in time to see a wall of water surging through the compartments below. The party and the survivors from the German crew had to jump clear for rescue by the corvettes’ boats as the U-boat quickly settled. One of the Canadians did not survive. Stoker W.I. Brown, RCNVR, Prentice later reported, “was known to be a strong swimmer and his life-belt was blown up. He had only a short distance to swim to the boat and was seen to push off from the submarine as she sank. It is thought that in some way he must have been caught up and drawn down with her as a thorough search was made by the boat and later by Chambly herself.”

U-501 was the RCN’s first confirmed

U-boat sinking. As fate would have it, the inexperienced Canadians had come up against an inexperienced submarine, in commission for only four and a half months, on its first operational mission, and making its first attack on a convoy. The commanding officer, 37-year-old Kapitänleutnant Hugo Forster, had joined the navy in 1923 but, as the British intelligence officers who interrogated him reported, “had only recently transferred to the U-boat branch. He had taken a shortened U-boat course and… his first and last cruise in command was in

‘U-501’… in the heat of the action, (Forster’s) resolution failed him, perhaps because he was rather older than the general run of U-boat captains.” The Admiralty staff judgment that although “Providence certainly took a hand and put the U-boat in the corvettes’ path… the destruction of a U-boat can never be a matter of luck alone; it can only be achieved by a well-handled ship with a well-trained crew, who know how to seize their opportunity” closely paraphrased Prentice’s own report. Prentice gave full credit to his crew: “Pickard’s superb navigation had put the corvettes in a tactically sound position, so that the asdic team could quickly and correctly track the submarine’s movements during a snap attack from a short approach, when the data was changing rapidly and difficult to interpret.” Prentice could have added that it was on the basis of his own astute analysis that he had insisted on the approach from ahead of the convoy, and the snap attack.

Hibbard thought that Chambly and Moose Jaw had caught U-82, but Rollmann was on the other side of the convoy, trying to push in between the columns. Fire from the merchant ships forced him into an emergency dive at 2155. Skeena swept the area, firing starshell, but contacted nothing and concluded the submarine was not an immediate threat. By this time escorts and merchant ships had destroyed, damaged, or forced under all the U-boats in close contact during the afternoon and early evening of Sept. 10. Nonetheless, U-433 was still at hand. U-432, which had made the initial sinking earlier the previous night, was again closing, as was U-202 and probably U-207 as well. At 2246,

U-433 fired a single torpedo that missed, and appears not to have exploded or been noticed by anyone in the convoy.

Twenty minutes later, Schultze in

U-432 fired two torpedoes and after more than three minutes saw an explosion on a distant steamer, probably the hit that sank the ship Garm, which was towards the rear of the second column. Kenogami, responding to an order from Skeena to rescue survivors, headed towards the stricken ship, but received a signal from one of the lead merchant ships on the port wing that a surfaced submarine was nearby. Within two minutes, at 2313, the corvette “sighted a submarine on the surface … the gun could not be brought to bear, however, and three minutes later it dived and we attacked with a 10-depth-charge pattern, which fell immediately in its wake. An excellent contact was maintained and at (2337) we carried out a deliberate attack. Three minutes afterwards the contact disappeared entirely.” Kenogami had found U-432, but the pattern was too shallow. Schultze believed there was more science to the convoy’s defence than in fact there was. He had noticed the Catalina with its navigation lights on, as had U-433 two hours earlier, and was convinced the aircraft had somehow located the submarine then homed the corvette on to it.

Meanwhile, U-433 had fired two torpedoes at 2308, just two minutes after Schultze’s salvo. Ey was not aware of the presence of U-432 and did not see the hit on Garm, but heard depth-charge attacks, presumably by Kenogami. He saw at least one escort put on a burst of speed and steer search courses, assumed he was the target of the hunt and broke off, not attempting another attack run until over an hour later.

The numerous explosions and counter-attacks brought the darkness to life,

and the battle scape gave pause to Kapitänleutnant Linder in U-202. “Observed explosion,” he recorded in his log at 2310: “To port there is a burning ship beyond the horizon. The convoy can be seen clearly. Both aircraft are overhead of it with their lights switched on. The escorts are almost continually firing illuminates, some merchant ships are firing machine-guns. These appear to be 2-cm. (bullets making a white line) and 3.7-cm. twin anti-aircraft guns, occasionally two red lines of light can be seen. In addition, the escorts are passing course or speed instructions using flashing lights, all in all the entire northern horizon is full of activity!” A close approach by an aircraft disrupted Linder’s observation and forced him under.

Moose Jaw and Chambly, having completed the rescue of U-501’s survivors, joined the convoy at 2315. Skeena’s starshell in search of Garm’s attacker illuminated the corvettes, and they were greeted by streams of tracer from some of the merchant ships before they could identify themselves. They were still taking up station, at 0032, Sept. 11, Chambly on the port bow of the convoy and Moose Jaw on the starboard beam, when Alberni, also to starboard, signalled that Stonepool at the head of the starboard column had been hit. A few minutes later, the ship following in the same column, Berury, was also torpedoed. Skeena headed towards the starboard flank, firing starshell, and a Catalina dropped parachute flares in the same area. At 0115, Skeena ordered Moose Jaw to search for survivors but, at that very moment the corvette came across Berury, still afloat. There were boats nearby and many men in the water, a large number of them dead. Alberni, the other corvette on the starboard side of the convoy, joined to assist in the rescue and to provide cover for Moose Jaw, as did Kenogami, which had evidently been pulling up from astern of the convoy after its hunt for U-432. Searching the water with the corvette’s small boats, pulling in the exhausted survivors, and then hoisting them up the side of the warship was slow work.

While the escorts were making the initial response to U-207’s attack, U-82 and U-202 were heading towards the van. At 0145 and 0148, U-202 fired two spreads of two torpedoes each at what appeared to be the two lead ships of a column, but they all missed. Then, between 0205 and 0208, Rollmann in U-82 fired three torpedoes that hit Scania and Empire Crossbill, the second and third ships in the fourth column, towards the port side of the convoy’s centre. Empire Crossbill, loaded with steel, plunged to the bottom with 49 people on board; the Swedish Scania, loaded with Canadian timber for Britain, remained afloat.

Hibbard, knowing that with the large number of submarines in contact, an attack on one side of the convoy would likely be quickly followed by a blow on the other, swept the starboard flank, while the corvette Chambly patrolled ahead and to port. These tactics were correct, for Linder in U-202 appears to have been on the starboard side: “Suddenly, starshells are fired over me from the horizon on exactly the same bearing as the merchant ship (that he had just attacked). These are bursting quite far from me but are sufficiently close to make me visible on the bright horizon.” Unknown to Hibbard, Skeena and Chambly were searching without support; he had assigned Moose Jaw alone for rescue duties after U-207’s attack, and his latest information had been that Alberni and Kenogami were returning to their stations. When Hibbard later discovered that they had been delayed picking up the survivors of Stonepool and Berury, he was sympathetic to the dilemma faced by the corvette captains, but was dismayed that the defences had been left so thin.

Rollmann, running low on fuel, made no attempt to remain in contact after his attack. The hits on the ships had created a large amount of smoke that he used to cover his retreat as he shaped course for home. Still in close pursuit of the convoy were U-84, U-202, U-207, U-432, U-433, and U-652. Between 0246 and 0705, U-202, U-432, and U-652 made four attacks, while U-84 and U-433’s attempts were thwarted by aircraft and, as the submarines reported, pursuits by the escorts. All of these attacks appear to have been made against the rear of the convoy, or against ships that had fallen astern, and none seem even to have been noticed by the intended victims, let alone to have triggered countermeasures by the escorts. Indeed, the three corvettes engaged in rescue work, Hibbard’s disapproval notwithstanding, had forced the U-boats to keep their distance. The submarine crews, after nearly 48 hours of intense operations, were reaching their limit. German Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz knew this, and broadcast admonitions during the morning of Sept. 11, refusing permission for U-652 to depart for port because it had expended all its torpedoes, and urging all boats “to do everything that the situation permits to make it easier for other U-boats to get at the enemy. No boat can break off pursuit of a convoy merely because of absence of torpedoes. It must push on and keep contact.”

Other submarines were coming up to help, but between 0730 and 0815 on the morning of Sept. 11, the Iceland reinforcement–five British destroyers of which HMS Douglas was the senior ship, the corvettes HMS Gladiolus, Wetaskiwin, and FNFL Mimosa, and the antisubmarine trawlers HMS Buttermere and Windermere–finally arrived. Commander W.E. Banks, RN, in Douglas took over as senior officer from Skeena. It was now possible to send ships out on sweeps for suspected shadowing U-boats. On the afternoon of Sept. 11, HMS Leamington and Veteran responded to an aircraft report, sighted what was almost certainly U-207 in the distance and made asdic contact after the submarine had dived. A four-hour hunt, joined in by two of the other British destroyers, produced no definite result, but U-207 was never heard from again. Declared missing by the commander of the German U-boat service from this date, postwar analysis confirmed it was sunk by the two destroyers first in contact.

During the early hours of Sept. 12, Skeena detached for Iceland and had only 20 tons of fuel oil, less than five per cent of capacity, left on arrival. Late that day the destroyers St. Croix and Columbia joined the screen. As SC 42 neared Iceland on Sept. 13-14, three United States Navy destroyers, Hughes, Russell, and Simms, carried out distant sweeps around the convoy, and responded to aircraft U-boat reports, but as one of the first combat patrols by American warships in direct support of a convoy, they were under instructions not to join the close escort. The U-boats, hampered by fog, had to stay down even when conditions cleared in the face of aggressive sweeps by the strengthened surface escort, and air cover that increased in scale as the convoy approached Iceland.

During the morning of Sept. 14, U-boat Command called off the six submarines still in pursuit. But the ordeal was not quite finished. On the morning of Sept. 16, when SC 42 was approaching northern Scotland, it was found that Grubb in Moose Jaw required hospitalization. Eleven days at sea in gruelling weather and combat conditions had taken a severe toll on the young corvette captain, who bore an especially heavy burden as virtually the only experienced member of the crew. Suffering from acute pain in his chest and stomach and unable to keep down food, he underwent examination by a medical officer from one of the British destroyers, who recommended that he be hospitalized immediately. Douglas directed St. Croix to escort the crowded, undermanned, and battered little warship into port.

That afternoon, as the two escorts emerged from a rain squall, they sighted Korvettenkapitän Gysae’s U-98. The boat crash-dived. St. Croix made asdic contact and delivered four depth-charge attacks, and British destroyers subsequently scoured the area, but U-98 escaped further detection. After nightfall Gysae attacked and sank MV Jedmoor, which had survived U-85’s failed initial salvoes on Sept. 9. Another iron ore carrier, she went down quickly; just six of 37 on board survived.

SC 42 was one of the worst convoy disasters of the war. Fifteen ships sunk and one severely damaged comprised nearly a quarter of those that had sailed. All but one loss took place between U-85’s initial contact on the morning of Sept. 9 and the arrival of large-scale reinforcements on the morning of Sept. 11, a span of 44 hours during which the tiny RCN escort held the ring alone. Of the approximately 625 people aboard the 15 ships lost, at least 203–approximately a third–lost their lives in fire, explosions, or drowning in the paralysing Arctic waters. Over 70,000 tons of cargo–a number that would have been considerably larger had not most vessels in the SC series been so pitifully small and old–went down with the ships. The material lost included 21,286 tons of high-grade iron ore, pig iron, and finished steel, 21,617 tons of wheat and other grains, 9,778 tons of chemicals, 9,300 tons of fuel oil, and over 10,000 tons of lumber–enough material to house and feed thousands of people, fill thousands of bombs and shells, and build several ships.

Circumstances had favoured the U-boats. Moderate seas in the opening stages of the battle helped them close the convoy once it had been sighted at long range in excellent visibility. Clear skies also enabled the U-boats to determine their positions accurately using celestial navigation, so that once the convoy was located the pack closed relentlessly without having to overcome plotting problems. Finally, excellent radio conditions facilitated the receipt of locating and shadowing reports. The commander of the German U-boat service had alerted the rest of the pack within 60 minutes of the initial sighting report, an impressive time for command and control systems of the time. SC 42 became a perfect target for the many U-boats, amply supplied with fuel and torpedoes, close at hand.

The reaction of Captain Stevens in Newfoundland was typical of comments on both sides of the Atlantic: This was “an appalling tale of disaster,” in which it was “impossible to criticize any single action of the Senior Officer, Lieutenant-Commander J.C. Hibbard, RCN…. On the contrary,” he continued, “I consider that he handled what must have appeared to be a hopeless situation with energy and initiative throughout, probably thereby averting worse disaster.”

Commodore Murray praised Hibbard for remaining alert and active during 66 hours of unremitting battle, and never losing hope, “which, with the meagre force at his disposal, a lesser man might have done.” He had “acquitted himself in a manner

of which the Royal Canadian Navy may well be proud.” The Admiralty’s Anti-Submarine Warfare Division classed the defence of SC 42 as “valiant” and praised the destruction of U-501 by Chambly and Moose Jaw as well as the “several promising attacks” by Skeena and Kenogami, and HMS Veteran and Leamington. As it later proved, they had severely damaged U-85 and destroyed U-207, besides driving back and possibly demoralizing several other boats at critical points in the battle. Strikingly, in view of the heavy losses, the people who most appreciated the escorts’ efforts were the masters of the ships in the convoy, experienced mariners not easily given to praise.

When SC 42 reached Loch Ewe on Sept. 17, they “unanimously and spontaneously” asked the naval control service officer to pass word directly to Admiral Sir Percy Noble, Commander-in-Chief, Western Approaches, of their “appreciation of the work of the escort vessels in endeavouring to protect Convoy SC 42 against the heavy and concentrated attacks made on the convoy by the enemy.” That said, the merchant ship crews themselves and the DEMS personnel who operated the armament of the cargo vessels deserved great credit for aggressiveness and skill. Quick, accurate radio reports of U-boat sightings enabled the escorts to carry out effective countermeasures, and the readiness with which the DEMS crews opened fire on surfaced submarines drove them off on at least two occasions.

The praise might well have been more fully shared with the aircrews of Coastal Command. The appearance of the Catalinas on Sept. 10 largely kept the pack at bay during daylight, and the aircrews’ persistence through that night deterred several of the German captains, convincing them that the RAF had developed much more effective means for aerial detection in darkness than actually existed. Even one of the U-boat commanders noted how exhausting the extended air patrols from Iceland must have been, and the close cover the Catalinas provided at night required skill at a time when equipment and techniques for over-water flying in darkness were not well developed.

One of Captain Stevens’s comments, when he read Hibbard’s report, was that although Hibbard had written it “during the only night in a month which HMCS Skeena spent in harbour,” it was exceptionally lucid. The historian is able to add, after comparing it with German war diaries, that Hibbard had a firm grasp of virtually every tactical twist and turn, over scores of square miles of ocean, from the beginning of the battle to the end. At most of the critical points, the Admiralty staff, after sifting a great deal of additional evidence, was able simply to reproduce Hibbard’s account in their detailed analysis. The clear, complete picture of events that Hibbard was able to maintain, together with the well-directed pursuit Skeena was therefore able to make in response to every significant contact, was the key to the defence. Here, in a nutshell, was why the river-class destroyers, and the seasoned, professional seamen who formed a large portion of their crews, had an importance far beyond their limited numbers in the RCN’s escort fleet.

As for the corvettes, it must be borne in mind that Alberni, Orillia, and Chambly had been on full-time operations for barely three months, while Moose Jaw and Kenogami had no operational experience whatsoever. Chambly and Moose Jaw’s destruction of U-501 was testament to Prentice’s tactical skill. And as already noted, the despatch of a raw ship like Moose Jaw to make her first cruise on the open ocean amidst a known large concentration of U-boats showed boldness, if not desperation, on the part of Prentice, who suggested it, and Murray and Stevens, who authorized it. Certainly, the mission and its outcome showed how great was the influence within the RCN of its small cadre of experienced professionals like Prentice. It also sheds light on the spirit within the NEF during its early days when the senior officers were willing to allow individuals like Prentice to take extraordinary risks in view of the gravity of the situation at sea. In this case, the gamble paid off with the destruction of

U-501. Despite a litany of errors on the part of Moose Jaw’s green complement, the ships struck at the right place at the right time. No less remarkable was the performance of Kenogami throughout the battle. Although this was the corvette’s first transatlantic mission, she chased down two U-boats in tricky night actions, and helped guide Skeena during the attack that damaged U-85.

Commander J.D. Prentice’s confidential report on the action not only serves as a moving tribute to the men under his command, it also helps explain why some of the corvettes, against all odds, succeeded from the time they entered service:

“The ship’s company carried out their duties efficiently and well although six months ago they were completely untrained and in the majority of cases had never been to sea in their lives before. This I attribute to the hard work and efficiency of my First Lieutenant (Lieutenant E.T. Simmons, RCNVR). This officer has been responsible almost entirely for the working up of the ship since during the training period at Halifax, the whole of my time was taken up with training programmes, etc., of the group of corvettes under my command. I had little or no time to give to my own ship. He has carried out his duties with a zeal and energy and an efficiency which has surprised me in one who has not before been to sea. I could not ask for a better First Lieutenant.”

The beleaguered Lieutenant Grubb, with his untried crew, also provided comments on personnel that give an insight into the unsuspected strengths–and weaknesses–among the people hurriedly thrown together to get Canada’s corvettes to sea in 1941. In relating the rescue of survivors from Berury and Stonepool in the early hours of Sept. 11, Grubb wrote:

“33. The energy and initiative of Mr Herbert W. Ruddle-Browne, Mate, RCNR (Temporary) was outstanding. It became evident to me in the early stages of the action, that the Executive Officer …was unequal to the task confronting him, and I therefore sent Mr Browne from the bridge to assist him. It is chiefly due to (Browne’s) efforts that so many men were saved and accommodated with a minimum of confusion….

“34. Sub-Lieutenant Harold E.T. Lawrence, RCNVR, went away in the boats in general charge, and many of the survivors, in my opinion, owe their lives to his initiative and ability….

“37. At 1015 the chief engine room artificer reported that he had run out of water feed for the boilers, and that it would be necessary to stop for about half an hour. I informed Skeena of this and Wetaskiwin was sent to screen. At 1035 the ship was again under weigh (sic). Enquiry into the matter showed that the Chief E.R.A. had forgotten to distill (sea water to make fresh water for the boilers) during the excitements of the night. It is considered that he should have done so during the previous day at the latest. This rating has shown himself inefficient throughout the entire cruise, with some signs of improvement lately.

“38. Two ratings were found to be drunk on board during the night. (A regular force) Leading Stoker…was seen to be drunk whilst the ship stopped to rescue the submarine survivors…. (an RCNR) Stoker Petty Officer…was seen to be drunk whilst the ship was shelling SS “Berury.” Neither of these ratings would state where they had obtained the liquor. They were both punished with 90 days detention.”

If the corvettes had performed surprisingly well under extremely adverse conditions, their routine operations revealed just how raw they were. Commander Banks, who took over as senior officer of the reinforced escort on Sept. 11, was scathing in his comments about the lack of communications discipline and the poor station-keeping by the NEF ships, both in his force and Hibbard’s original group:

“(1) R/T (radio telephone) and P/L (plain language, i.e., unencoded messages) was used without reason, i.e., not in the presence of enemy. (2) R/T and P/L was used indiscreetly, i.e., ships trying to join convoy in fog used P/L “where is convoy,” “I think it is about 3′ 140_,” “join me at port side of convoy,” “we are returning to Iceland,” etc. (3) Station keeping appalling, i.e, Corvette Moose Jaw actually crossed my bow when supposed to be on A/S screen in daylight in a position 2 miles from Douglas and at night they were all over the place. (4) When the convoy altered course escorts either proceeded on same course or took up new positions slowly.”

These problems reflected lack of training and the impossibility, given the pressure of operational schedules that continually became more demanding, to form the NEF ships into stable groups. As Hibbard commented, “The 24th group, having only recently been formed, a far greater volume of signals was necessary than would ordinarily be the case where ships of an escort group know and understand the Senior Officer of the Escort’s intentions.” Lieutenant Briggs of Orillia, in his commentary on the battle, suggested that over reliance on insecure radio telephone, and the failure of ships to manoeuvre quickly and accurately in response to orders flashed by signal light, lay in difficulties in bringing newly recruited signalmen up to speed in this challenging art:

“Signalman (sic) drafted to corvettes in some cases have never seen a signal projector. Practically none have ever used one. We find that no doubt a signal man can read a lamp if comfortably installed in a classroom. He can also send–on a (radio) key. Suggest that signalmen in training be given opportunity to use projector and learn how to “train” light. The story is very different when they have to contend with violent motion in a corvette. Have to keep light trained, read and send in blinding rain, hail, snow, spray and also pick it out in a fog. We realize that a signalman is being asked to acquire a great deal of knowledge in a very short time and we think they do very well all things considered, but if possible, would further suggest that signalmen be trained for hot work…. In other words concentrate on certain phases and become proficient, rather than have a smattering of knowledge of all aspects of the work. Would submit it is not too far fetched to suggest that a platform be built in such a manner that it can be mechanically manipulated to represent a heaving, pitching or rolling ship. Signalmen could even be dressed in oilskins and a shower device played on them to represent the misery of rain etc, when pads get wet and eyes are blinded.”

Interestingly, Briggs’s suggestion about the use of simulation equipment in training establishments, an idea he got from the air force’s mechanical simulators, prefigured in some respects the revolutionary Night Attack Teacher Hibbard himself would develop at Halifax in 1942. As it was, Briggs’s comments lent convincing weight to Banks’s devastating criticisms.

Because this convoy was up against great odds, and so small a “band of brothers” faced those odds with such slender resources, it had the flavour of a heroic saga. When the distinguished Canadian poet E.J. Pratt accepted an invitation to write an epic poem about the navy’s wartime achievements, and found that his original subject, the tribal-class destroyer HMCS Haida, was already to be the subject of a book, he turned without hesitation to the exploits of Skeena and SC 42. The result was Behind the Log, perhaps the only narrative poem ever to chronicle a North Atlantic convoy battle. “Apart from a few minor transpositions and enlargements for dramatic effect for which official indulgence is requested,” wrote Pratt, “the record follows the incident”:

When ships announced their wounds by rockets, wrote

Their own obituaries in flame that soared

Like some neurotic and untimely sunrise

Exploding tankers turned the sky

to canvas,

Soaked it in orange fire, kindled the sea,

Then carpeted their graves with wreaths of soot …

Only the names remained uncharred …

Merely heroic memories by morning.

Pratt could hardly have chosen better.

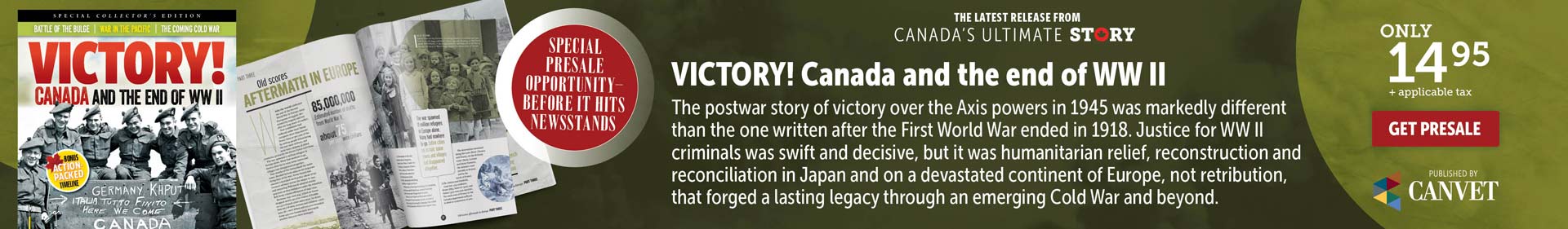

Advertisement