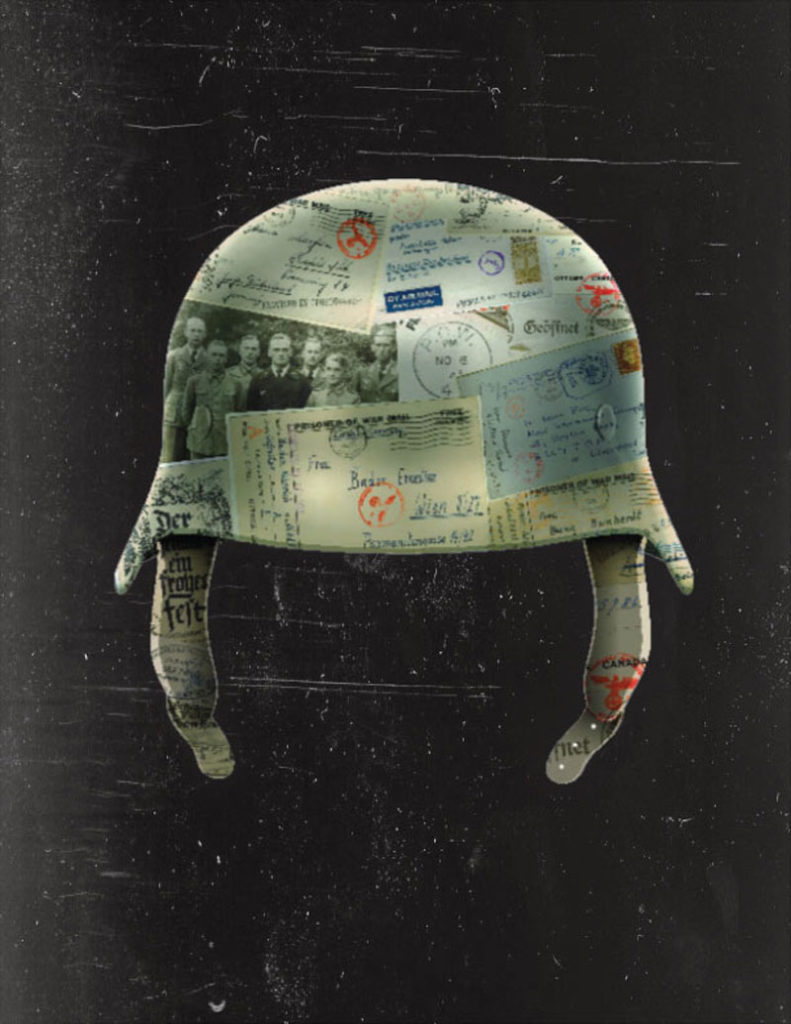

A montage includes postcards and letters from German prisoners of war in Canada on a Second World War helmet. [Postal History Corner Blogspot- Modified by Mauricio Dimate].

Fanatical members of the Harikari Club plotted to escape, slaughter civilians, and wreak as much havoc as possible.

About 34,000 German prisoners of war were housed in more than two dozen internment camps across Canada during the Second World War. Most were enlisted or conscripted soldiers serving their country in time of war. Most were peaceful prisoners.Thousands even emigrated here after the war. But among them were dedicated and fanatical Nazis determined to uphold their fascist philosophy while imprisoned—and not go gently at war’s end. Nazis established their own regime behind the barbed wire.

Under terms of the Geneva Conventions, prisoners of war were allowed to choose their own internal leaders; in camps with plenty of fascists, Nazis soon assumed the roles. They were arrogant, defiant, aggressive, well-organized and well-armed—with clubs, knives and other weapons made from scrounged material.

“Because they believed Canada would someday be invaded by German armed forces and become a colony of Nazi Germany, many German officers worked to keep the Nazi spirit alive inside the camp,” wrote Martin Auger in an article in Canadian Military History entitled “The HARIKARI Club.” ‘Hara-kiri’ is the historic Japanese samurai warrior suicide ritual.

They formed intelligence sections to spy on fellow prisoners and control news of the war in the camps, propaganda sections to keep prisoners in the Nazi fold, escape committees and their own Gestapo units to brutalize those judged as traitors to the cause.In 1941, a German prisoner kangaroo court in a British PoW camp tried and convicted a U-boat captain in absentia for cowardice.

“Although the sentence had been passed in a camp in Britain, it was enforced in Canadian Camp 44,” wrote prisoner Franz-Karl Stanzel in a 2018 Canadian Military History article about his experiences as a PoW. (Camp 44 in Grande-Ligne, Que., 50 kilometres southeast of Montreal, opened in 1943.) The captain was kept in solitary confinement by fellow prisoners, denied personal comforts and ostracized.Similar Nazi organizations existed at other camps and woe betide prisoners who expressed different political ideas or questioned Nazi leadership.

Prisoners of war pose with pets at the Whitewater labour camp 300 kilometres northwest of Winnipeg. [CWM/19840579-058].

“The Gestapo element…is extremely active,” wrote Captain J.A. Milne, an intelligence officer quoted by J.J. Kelly in an article for the Dalhousie Review.

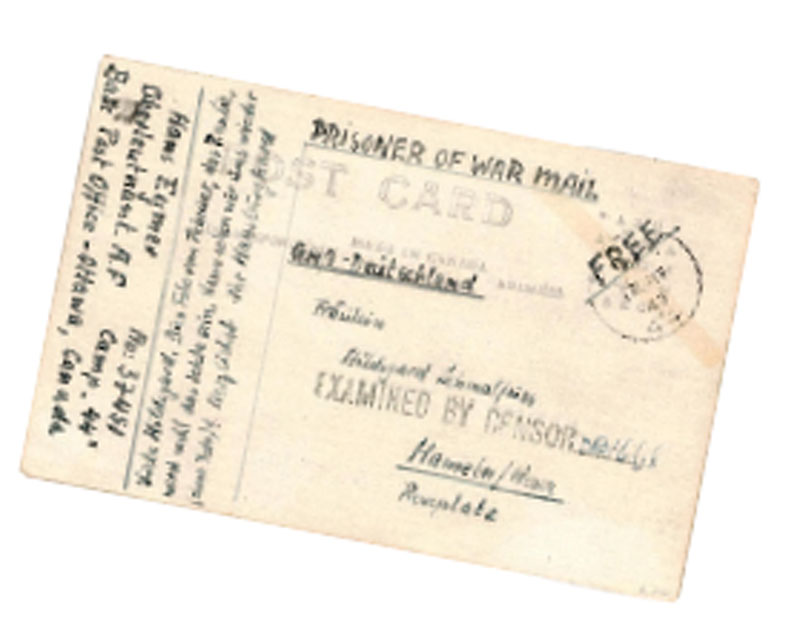

Members of the Nazi secret police threatened immediate punishment of fellow PoWs who provided information to camp staff, to be followed by a court martial with the death penalty in Germany after the war. In April 1943, for example, outgoing mail from Camp 40 in Farnham, Que., 65 kilometres southeast of Montreal, was found to include a pack of cigarette papers containing a smuggled letter destined for Germany listing names of prisoners deemed anti-Nazi.

Immediate Gestapo punishment included physical beatings and psychological torment. “Prisoners threatened by Nazis feared for their lives; finding a noose in one’s bed was extremely traumatizing,” wrote Auger in Prisoners on the Home Front.

Camp Gestapo monitored the prisoners’ mail to keep news of Nazi setbacks out of the camp, identify anti-Nazis, and keep prisoners in line by threatening to withhold it. “Holding back prisoner-of-war mail is probably even more effective than beatings as a means of making the prisoners of war a ‘loyal’ Nazi,” reported one intelligence director.

“Under the influence of the Gestapo element, everyone was watched by everyone else,” wrote a prisoner in Medicine Hat, Alta., whose diary was included in a 1944 intelligence report quoted by Kelly. “Were we not a German island in enemy land? It is clear that one [could] not have an opinion of his own.”The Gestapo was also responsible for a riot in July 1942 in the temporary camp that housed about 10,000 PoWs in Ozada, Alta., 70 kilometres west of Calgary.

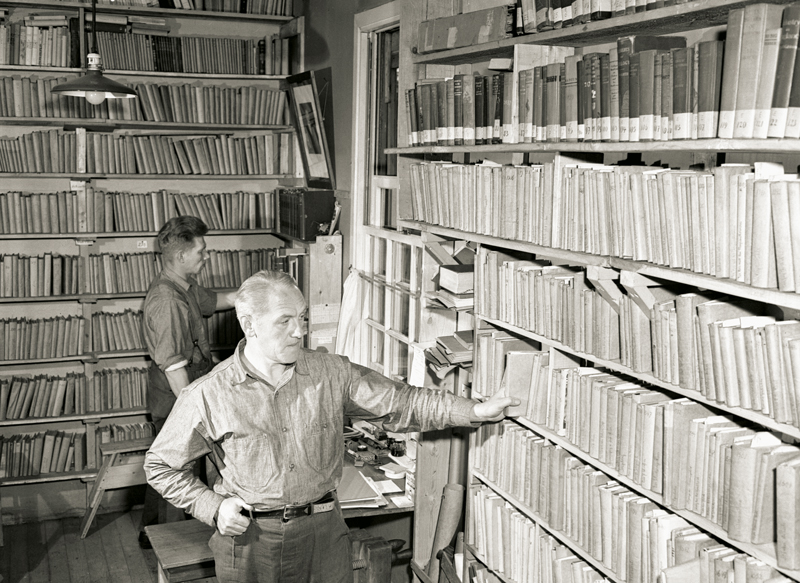

German prisoners of war use the library at Camp 42 in Sherbrooke, Que., on June 18, 1944. [E.Ehrenreich/CWM/20090083-003].

In July 1943, seven PoW officers were transferred to Medicine Hat with orders from General Artur Schmitt, Canada’s highest-ranking German prisoner of war, who decreed that suspected traitors were to be identified and killed.

“All possible affairs of the camp…were then carried through as if ordered by General Schmidt [sic],” wrote the prisoner. “Such a spy system stated that no one could say a word anymore. Beatings were daily occurrences….

“It was the privilege of the Gestapo to stroll through the camp at night and do their dirty work. Some prisoners of war were tired of being duped any more by these uniformed tramps and got together to bring about an overthrow of these elements.”

But they were betrayed. Several were brought in by camp Gestapo for questioning on July 22. Even before questioning began, prisoner August Plaszek was seized, beaten bloody, then hanged. A military court of inquiry said that while those guilty were not found, “a good many prisoners of war, strongly Nazi, who either assisted in, connived at, or approved of the hanging, were uncovered.”

There was a second murder in the Medicine Hat camp in September 1943. Teacher Karl Lehmann, who translated newspaper reports for use in his camp classroom, had the misfortune of musing aloud about the possibility of a German defeat. He was also beaten and hanged.

A code of secrecy enforced by camp Gestapo stymied the murder investigations at the time, but PoWs were not returned home until well after hostilities ceased and the military occupation of Germany ended. More fruitful investigation continued after the war, followed by murder trials. RCMP undercover agent George Krause was assigned to investigate Lehmann’s murder.

“By this time, the Nazi element had lost their control over inmates and the previous rule of fear disappeared,” he said, quoted in David J. Carter’s Behind Canadian Barbed Wire. “The prisoners we contacted did not refuse knowledge or information when we questioned them” after the war.

In 1946, four PoWs were hanged for Lehmann’s murder. Three others— Johannes Wittinger, Adolph Kratz and Werner Schwalb—were tried for the murder of Plaszek. Wittinger was acquitted and Kratz’s death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. A staunch Nazi and former panzer gunner who earned the Iron Cross in 1940, Schwalb offered to testify in the Lehmann trial in return for clemency but was turned down. He was hanged on June 26, 1946, in Lethbridge, Alta.Schwalb’s last words were, “My Führer,I follow thee.”

Photographs of prisoners, including these in Grande-Ligne, Que., were reproduced on postcards sent to family and friends in Germany. Even when passed by censors, some contained secret messages in invisible ink.[Postal History Corner Blogspot]

Even when passed by censors, some contained secret messages in invisible ink. [Postal History Corner Blogspot]

They believed Canada would someday be invaded by German armed forces

The propaganda section organized Nazi celebrations, complete with regalia, wrote Auger. It also held secret lectures on Nazism and provided a forum for honing officers’ military skills. A highlight of Hitler’s birthday celebration at the camp in April 1944 was a speech by General Johann von Ravenstein, who was backed by two enormous swastika flags, wrote Grande-Ligne prisoner Stanzel. “The Canadians turned a blind eye to this as if it were none of their concern.”

The intelligence section kept abreast of war developments using a jury-rigged radio made from scrounged wire, tin cans, aluminum foil and an amplifier from a record player. Stanzel believed the radio tubes were smuggled in with a food delivery by Nazi supporters outside the wire. The intelligence section also passed messages among the camps and to Germany. Ordinary correspondence contained separate ‘invisible’ messages written in ink from milk, oranges, potatoes or urine that could be decoded by recipients.

The escape committees were like those of Allied prisoners in Europe, who employed much the same tactics, and for much the same reason: Allied and Axis PoWs believed escape to be a duty (see “Prisoners of War,” March/April and May/June 2018).

Thousands of Allied PoWs attempted escapes and many downed air crews eluded escape to rejoin their comrades and continue the fight. “From the moment of capture, your first thought is to try to escape,” wrote Canadian Staff Sergeant R.E. Crumb, taken prisoner in the raid on Dieppe, France, in August 1942. “The thought possesses you day and night. You examine every possibility.” It took him six attempts until he finally made it in April 1945, reuniting with Allied troops just as the war in Europe was ending.

There were only about 600 escape attempts reported in Canada. This was partly because capture was almost certain (what with needing to go undetected across a continent and an ocean to get back home) and partly because many PoWs enjoyed better living conditions in Canada than the privations of wartime Europe.

“I can…state positively that 70 per cent of prisoners of war had not fared so well at home as they did here,” said a Medicine Hat prisoner quoted by Kelly. Canada lived up to its Geneva Convention obligations, providing good-quality food and lodgings, recreation opportunities such as sports, drama clubs and orchestras, and academic courses and training in trades.

Only one German prisoner is known to have made it back to Europe. Fighter pilot Franz von Werra, who had already been recaptured twice in Britain, was sent to Canada where he leapt from a train on the way to an Ontario PoW camp. He made his way to the southern border and crossed over to the United States before it joined the war. Diplomacy found him a route back to Germany.

Many PoWs turned to simple pursuits to pass the time: mending clothing in Grande-Ligne, and playing chess in Farnham in Sherbrooke. [DND/LAC/PA-163785;].

Most escapees headed for the U.S., where they could get help from German sympathizers. After escaping from Gravenhurst camp in August 1944, Luftwaffe Lieutenant Walter Manhard managed to live undercover in the U.S., even marrying an American navy officer. In 1952, he turned himself in.

Several mass escapes were plotted. In 1941, a 45-metre tunnel in Camp X in Ontario was meant to facilitate a mass escape of 80 prisoners on April 20, Hitler’s birthday. But plans were moved up due to heavy rains: on April 18, 28 PoWs escaped and spread out across the country. Two were killed in the ensuing week-long, nationwide manhunt in which prisoners were recaptured in Montreal, Ottawa, near the Ontario-U.S. border and near Medicine Hat.

The first escapes from the Grande-Ligne camp were spy expeditions. Escapees were tasked with reconnoitering bridges, factories and airfields and the data was shared with the camp intelligence section (and likely passed on to Germany).

“The Nazi government is conducting a systematic campaign amongst PoWs in Canada,” noted a Canadian intelligence memo in 1944, “to preserve them as a physically fit, well trained and thoroughly indoctrinated body of soldiers to continue the struggle for power even after a German military defeat.”

“Finding a noose in one’s bed was extremely traumatizing.”

In August 1944, Canada’s Psychological Warfare Committee began identifying Nazis, anti-Nazis and those with no political convictions and separating them in different camps. The staunchest Nazis were in Camp 44, where nefarious plans were already afoot.

Depressed by the D-Day landings in June 1944, senior Nazi officers in the Grande-Ligne camp created the Harikari Club, named after the samurai ritual. The club made plans to carry on the war in Canada if Germany capitulated, plotting to murder anti-Nazi prisoners and as many camp staff as they could, storm the guard towers and break out, go to industrial areas and airports, kill as many people and do as much damage as possible before being killed. Capture was not an option.

“Their only thought is to go to their deaths in a final blaze of glory, taking as many of the enemy and as much of his property as possible with them to destruction,” reported Colonel W.W. Murray, director of military intelligence.But Roman Catholic priest Georg Felber, a German civilian internee, spilled the beans to camp intelligence officers on Oct. 3, 1944, in a letter outlining the club’s plans and identifying the ringleaders and a list of about 100 supporters.

The information was confirmed nine days later in the interrogation of anti-Nazi prisoner Alois Frank, who went to Montreal for medical treatment. He identified some of the targets, including munitions dumps at nearby airports. His list of names was nearly identical to Felber’s.

Canada inadvertently created think tanks for Nazi terrorism.

Canadian intelligence services and camp officials girded for the worst, having learned how much damage was done in a mass escape in Cowra, Australia, just weeks earlier. More than 900 Japanese PoWs set the compound on fire, charged and overcame armed guards in six towers and two machine-gun crews and scrambled over the fences. Nearly 400 prisoners made it out and spread across the countryside. Four guards and more than 200 PoWs were killed, some committed suicide, and more than 100 were injured in the nine days it took to round them all up.

Grande-Ligne was within striking distance of Montreal and industrial plants, shipyards, military installations, airports. Essential war facilities and irreplaceable war workers could be lost in such an attack. First, security was beefed up at Grande-Ligne with the addition of an armoured fighting vehicle and a universal carrier, six Vickers heavy machine guns, portable radio sets (in case communication lines were cut), tear-gas generators, grenades and parachute flares. Guard towers were reinforced and six machine-gun posts were installed, extra barbed wire was put up and more guards were brought in. Veterans Guard reserve platoons were stationed nearby if backup was needed.

Steps were taken to increase security at electric power plants, war factories, shipyards, ammunition dumps, airports, bridges and railway stations. Freight and passenger trains were monitored. Two Veterans Guard platoons were tasked with protecting civilians if a breakout occurred. The military aircraft of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan at Saint-Jean could be tapped for aerial reconnaissance. RCMP, border patrols, provincial and state police and the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation were all alerted.

Troublesome Nazi prisoners in Quebec were rounded up and sent to Kananaskis Camp in Alberta, where escape was more difficult. [W.J. Oliver/LAC/PA-188743].

In December, Canada turned down a British request to take on 50,000 more German PoWs from overcrowded European camps.“Cabinet decided not to increase the number…because those we have are a real menace,” Prime Minister Mackenzie King wrote in his diary. “We have not sufficient adequate protection for them and there is reason to believe they are forming suicide squads which may cause great trouble later on.”The wisdom of that decision was borne out on Dec. 30, when a routine inspection in Grande-Ligne turned up an anonymous letter warning of upcoming violence and urging the transfer of Nazi officers involved.

Transfers had already been discussed. “The danger of continuing to allow the present rabid clique of Nazi officers to remain at Grande-Ligne becomes increasingly more apparent,” said Eric Acland of the directorate of military intelligence, quoted by Auger. But others feared transferring Nazi leaders to new camps would result in spreading the idea of mass escapes across the country.It was decided to transfer troublesome Nazis to a camp far from urban centres, airports and industrial facilities. Camp 130 in the Rocky Mountains near Seebe, Alta., was considered ideal.

Built in 1939 and locally called Kananaskis Camp, it was about 80 kilometres west of Calgary. It had seven main and two secondary watchtowers and was surrounded by an electric chain-link fence. An eighth tower, which survives to this day, was added after an escape tunnel was uncovered.

In the middle of the night on Feb. 6, 1945, more than 100 fanatical Nazis in Grande-Ligne camp were rounded up. The camp was thoroughly searched and the radio receiver and various aids for escape and evasion were seized.The prisoners were uneventfully transferred to Camp 130. Young officers wanted to carry on the Harikari Club plans there, but they fizzled for lack of support.

At Grande-Ligne, Nazi fervour faded and programs to familiarize prisoners with democratic institutions—called de-Nazification—were put in place. By the time Germany surrendered in May 1945, Nazism was no longer a threat in Canadian prisoner of war camps, mostly for fear that bad behaviour might delay the repatriation process. At the end of the war, everybody just wanted to go home. Everybody, that is, except the 6,000 or so German PoWs who applied to stay.

Great, and not so great, escapes

Military prisoners consider escape a duty—but some obviously felt more duty-bound than others. Perhaps Karl Rabe, a physician and Kriegsmarine U-boat sailor, was the most dutiful of all, even though he was foiled five times.Rabe was captured when U-35 was scuttled in November 1939. He escaped from a hospital in Toronto, stole a boat, and tried to row across Lake Ontario to the United States, but he became disoriented in fog and came ashore on the Canadian side.

He made four more attempts from a prison camp in Lethbridge, Alta., in 1943, each more elaborate than the one before. He hid in a wooden box used for bread delivery and tried to saw his way out. The noise of the saw attracted a crowd of guards who cheerfully escorted him to a cell back inside the camp.He was given a two-week detention, a punishment repeated for the next attempt, when he escaped through storm drains, got hung up on the exit grating and had to call for help.

Next, he rigged a zip-line device on electric wires to get over the fence, but the wires drooped, stranding him in the dark too far above ground to jump. Fellow prisoners answered the call for help this time, so no punishment ensued.In his most elaborate attempt, Rabe tore apart sleeping bags, dipped them in a glue solution, and sewed them together to make a hot air balloon. He filled it with heating gas until it resembled a monstrous pumpkin, but it was heavier than air and did not lift off. Rabe and Wile E. Coyote, soul mates.

Rabe was promoted during the war, from matrose, the German navy’s lowest rank, to oberleutnant, perhaps due to his many escape attempts. After the war, he returned to Germany and practised medicine.There were other great escapes, and escape attempts, in Canada.After being recaptured twice in Britain—once while trying to steal an aircraft—Franz von Werra escaped a third time en route to a PoW camp in Ontario on Jan. 21, 1941. He went to the U.S., neutral at the time, then made his way back to Europe.

Only one German prisoner is known to have made it back to Europe.

On April 18, 1941, guards at the Angler Camp on Lake Superior discovered a mass breakout in progress: 28 of 80 PoWs made it to freedom through a 45-metre tunnel. Two were killed and the remainder recaptured.Ulrich Steinhilper, disguised as a painter, used a ladder to escape over barbed-wire fences on Feb. 18, 1942, making it to Watertown, N.Y., where he was recaptured. It was his third, but not final, escape attempt—he tried twice more.

Peter Krug escaped from the Bowmanville, Ont., camp on April 17, 1942, and was recaptured in San Antonio, Texas, having been slipped the addresses of sympathizers in the U.S. He escaped again, and was caught again in October 1943.Nineteen prisoners escaped through a drainage pipe in Kingston, Ont., in August 1943, but were soon recaptured.

An escape from Bowmanville camp was orchestrated from Germany in 1943. Canadian officials allowed the plan, hoping to capture a U-boat. Four prisoners were to escape through a tunnel in September and rendezvous with a U-boat. But the tunnel collapsed and, in the confusion, a different PoW, Wolfgang Heyda, sneaked over the barbed wire and made his way to the meeting point 1,400 kilometres away. He was recaptured, and the U-boat got away. Who can blame Max Weidauer for escaping in August 1944 from murderous Nazis in Medicine Hat camp who killed a fellow prisoner? He was temporarily sheltered by a local farmer and for his own protection was sent to a different camp.

Advertisement