U-889 sails on the Atlantic after its surrender in May 1945. [Courtesy of Jim Stewart]

It was a cloudy

afternoon on May 10, 1945, when four Canadian navy ships intercepted U-889 some 250 kilometres southeast of Cape Race, Nfld. The patrol aircraft that discovered the steaming German submarine circled overhead.

The war had been over less than a week and all German U-boats had been ordered to cease offensive operations, even before the surrender was formalized.

Almost three-quarters of the Unterseeboot crews had died during the war—an unheard of 28,000 of 40,000 men, many of whom fell victim to technologies that outpaced their own. The surrender order no doubt came as bittersweet relief to many in a service that had diminished from primarily volunteer to increasingly pressed crews.

“To all U-boats,” said naval high command on May 3. “By the acceptance of unconditional surrender, all German vessels of war are to discontinue unconditionally sinkings of ships and destruction of military and non-military installations and plants in the whole operational area of the German Navy.

“Violations mean a serious offence against the express will of the Grand Admiral and will bring serious consequences on the German people.”

There were 156 U-boats at sea when the order came down. They were initially told to repair to Norway “unseen,” under “absolute security.” The secret plan was to scuttle the lot to keep them out of Allied hands. While it failed to match the development of Allied sonar and long-range aircraft, the German undersea fleet had technology superior to virtually any in the world at the time.

As a result, many U-boats were destroyed or damaged beyond repair by their crews’ own hands in German waters during the first week of May:

- On May 1, three were wrecked at Warnemünde, on the Baltic coast.

- On May 2, another 32 were scuttled at Travemünde, near Lübeck.

- On May 3, 39 were destroyed—32 at Kiel and seven at Hamburg.

- On May 4, two were scuttled in the Kiel Canal and two at Flensburg.

That same day, May 4, the Supreme Allied Commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, allowed German forces in Northwest Europe, including naval forces, to surrender to British Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery.

Montgomery insisted that the Kriegsmarine, including the U-boat arm, surrender intact effective the following morning.

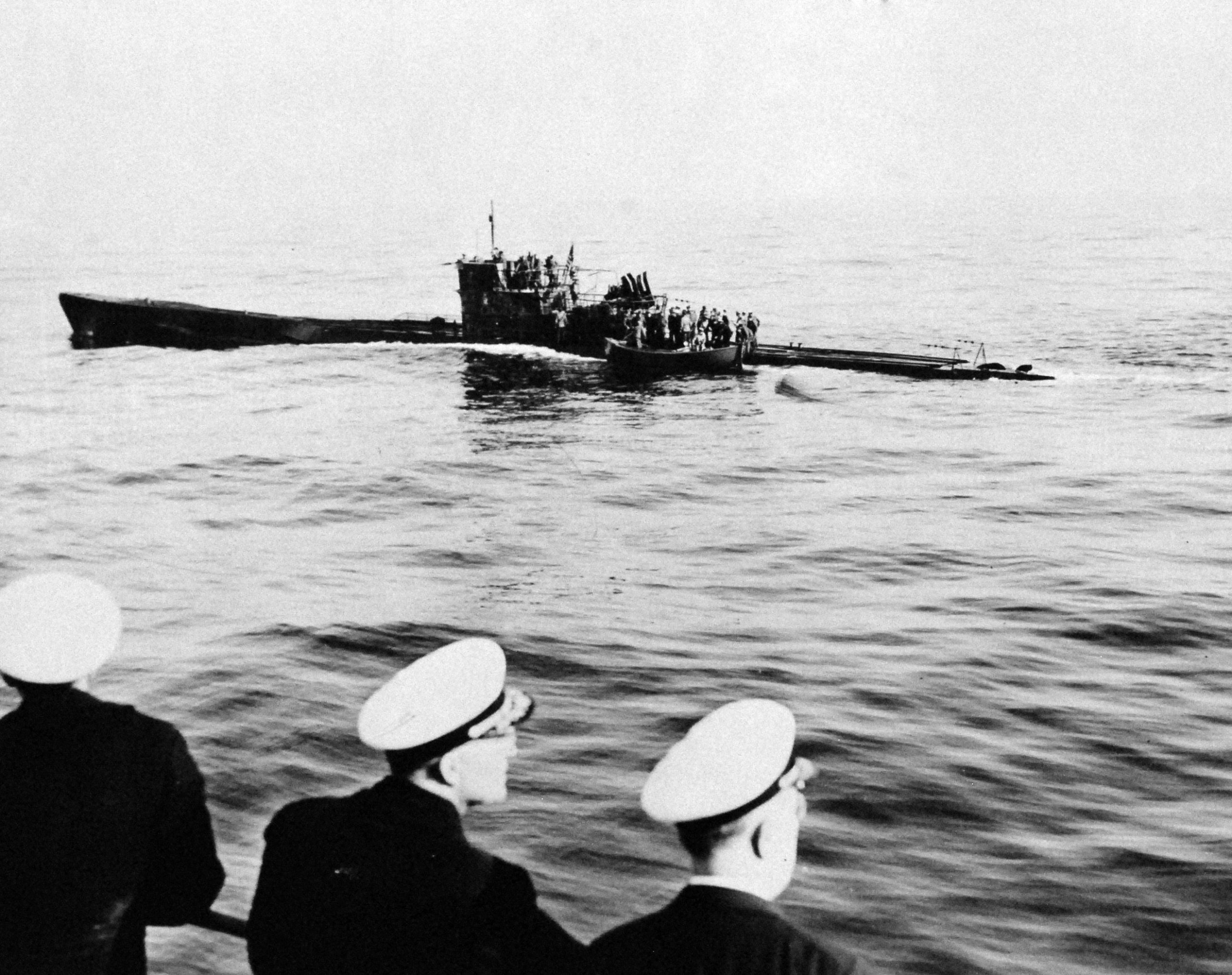

U.S. Marines search crew members of German submarine U-858, off Cape May, N.J., in May 1945. [U.S. Navy Archives 80-G-700486]

Nevertheless, dozens of boats were destroyed on May 5—64 on the Baltic, 23 along the North Sea coast. By May 7, at least 195 U-boats had been scuttled.

The German naval high command subsequently relented.

“Neither sink nor destroy U-boats,” it said on May 8, the day of the unconditional surrender. “Only through them can hundreds of thousands of German lives be saved.”

At least 150 U-boats were surrendered to the Allied navies, either at sea or at their operational bases.

The last message from Admiral Karl Dönitz, their long-time commander and now Hitler’s replacement as führer, was simple and direct. “After an incomparably heroic struggle, you have laid down your arms,” he signalled on May 10. “You have accomplished unheard-of deeds.

“You still have to offer to your Fatherland the greatest sacrifice of all by executing unconditionally the following instructions. Thereby you will not be staining your honour, but by so doing, you will dispel very serious penalties for your homeland.”

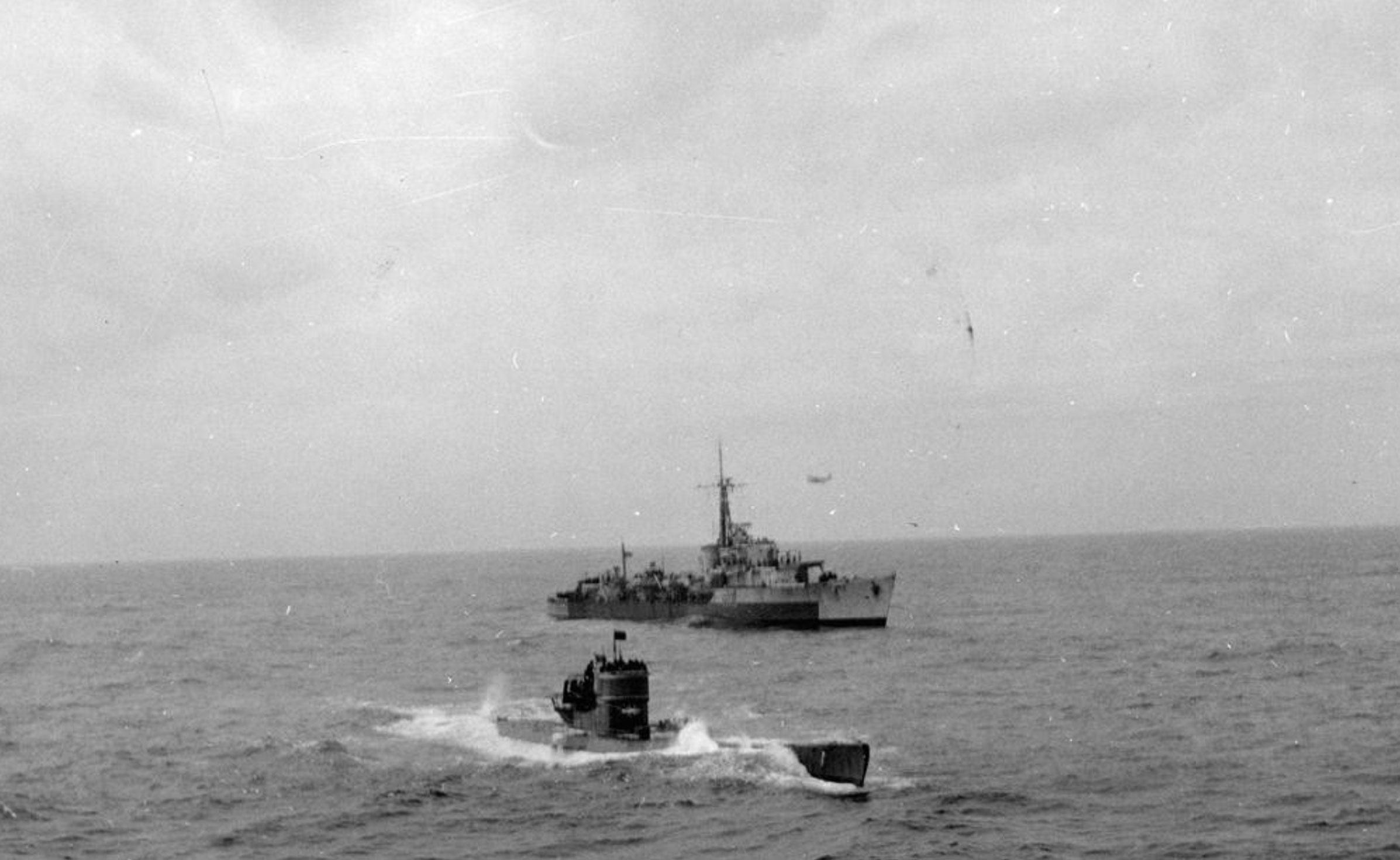

Flying a black flag, U-516 surrenders and is escorted by HMS Cavendish. [IWM/A-28554]

Commanded by Kapitänleutnant Friedrich Braeucker and crewed by four officers and 44 enlisted, the vessel was to be taken to Bay Bulls, Nfld.

But the orders changed and the Type IXC/40 U-boat—slightly larger than its predecessor, the IXC—was ordered into Shelburne, N.S., where its crew could be taken for interrogation and higher-ups could inspect the sub’s new-generation hydrophone gear and acoustic torpedoes. Commissioned at Bremen, Germany, just nine months earlier, the boat itself was so new it had never fired a shot in anger.

Braeucker officially surrendered May 13 off the Shelburne Whistle Buoy, 10 kilometres from the anti-submarine boom gate.

He and his crew were taken off the sub and transferred to Halifax, where they were interned in the naval dockyard. The submarine was commissioned into the Royal Canadian Navy the following day.

U-889 would become one of 10 U-boats allocated to the United States as part of the Tripartite Naval Commission in Berlin in November 1945.

U-190 arrives in St. John’s in June 1945 after surrendering to Royal Canadian Navy sailors off the coast of Newfoundland on May 12, 1945. [LAC/PA-145584]

Among others taken off the East Coast was U-190, which met the Canadian frigate HMCS Victoriaville 800 kilometres off Cape Race on May 11. The sub’s crew was taken prisoner and it was escorted into Bay Bulls under Canadian command.

With two sinkings on its record, including HMCS Esquimalt at a cost of 44 Canadian lives, U-190 was formally commissioned into the Royal Canadian Navy on May 19, 1945. Its first assignment was a summer 1945 tour of communities along the St. Lawrence River and Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Based in Halifax, the boat became an anti-submarine training vessel for the next year and a half. U-190 was paid off on July 24, 1947. It was painted in red-and-yellow stripes, then towed to the spot where it had sunk Esquimalt off Halifax Harbour. At precisely 11 a.m. on Oct. 21, 1947—Trafalgar Day—a spectacular lightshow began as the then-mighty Canadian navy unleashed an impressive firepower display, both airborne and seaborne, sinking its former adversary in 20 minutes.

U-190’s periscope now resides in the Crow’s Nest, a wartime officers’ club that still exists in St. John’s, N.L.

Advertisement