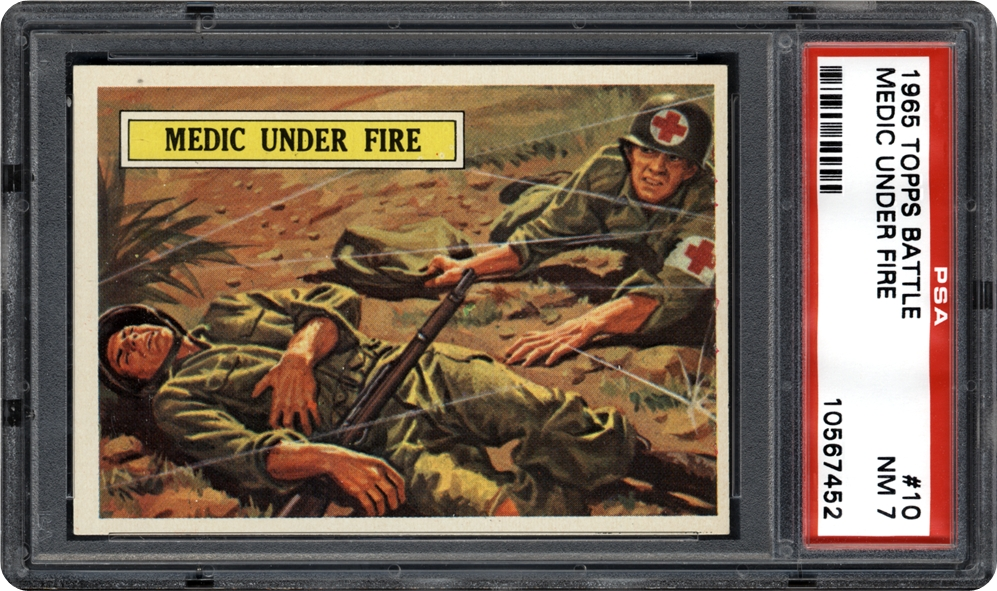

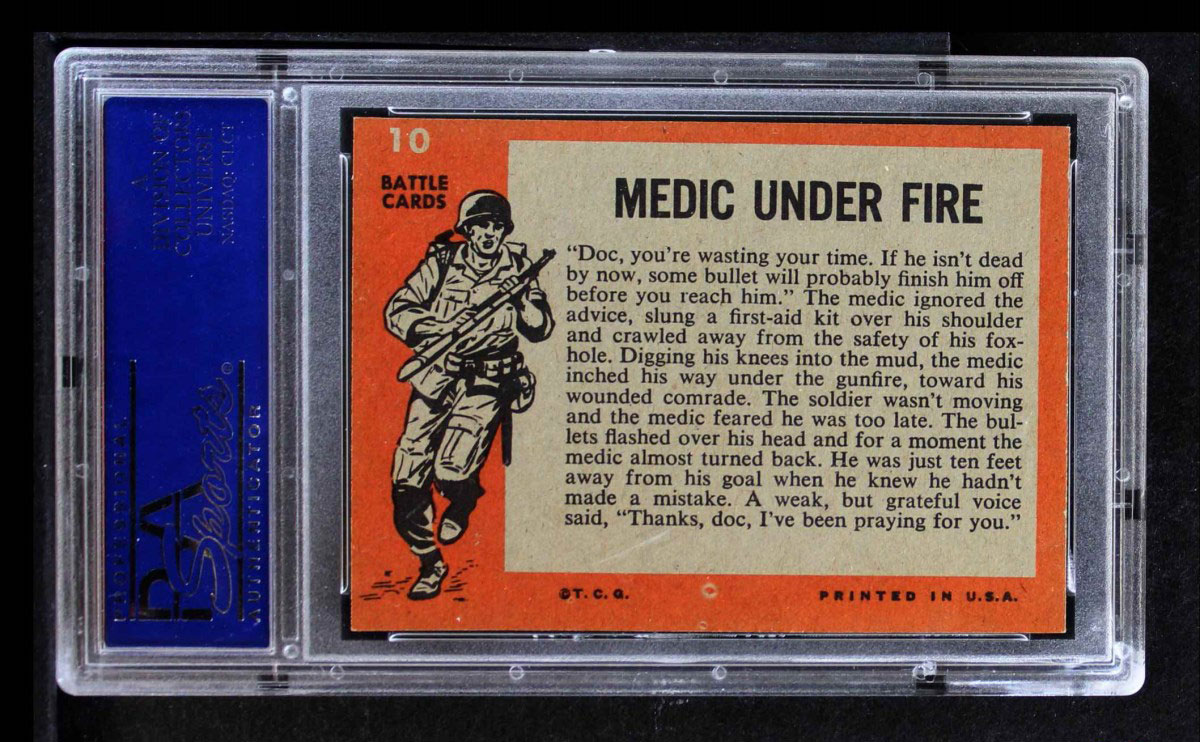

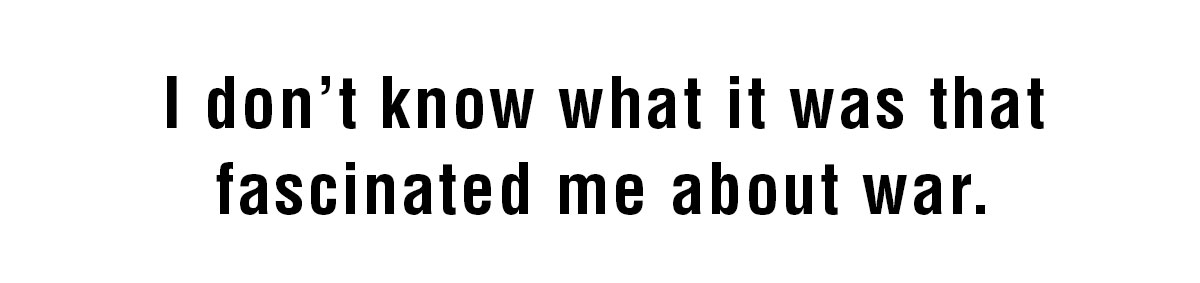

Medic Under Fire: The 1965 Topps card series was entitled “Battle: The Story of World War II.” The 66 cards were illustrated, violent and included the fictional stories behind the pictures on the back. [Topps]

It’s snowing as I write this—heavily. They tell us to expect 40 centimetres in Ottawa. It’s one of those storms that I remember as a kid, before the responsibility of shoveling—or much responsibility at all—was foisted upon me.

In those days, winter storms were somehow always big and what excited me most then, and what I remember with great fondness and no small amount of awe now, is that they meant a new round of war play—new forts, tunnels, trenches, bunkers, and epic snowball fights.

I don’t know what it was that fascinated me about war when I was a kid, but I seemed to spend an awful lot of time immersed in its history, and myth, at a very young age. We all did.

When not eating, sleeping or going to school, we baby-boomer kids spent most of the 1960s outdoors—riding bicycles, playing hockey in the street or on backyard rinks, and playing war.

Our parents didn’t seem to have a problem with this. Indeed, many of the toys we got for Christmases and birthdays were war-related—G.I. Joes, aircraft and battleship models, berets and plastic versions of the American G.I. helmet, along with toy weapons that could very well get you arrested in this day and age.

We were just 20 years out from the end of the Second World War—just about as long as they have been fighting in Afghanistan. Many of my doctor father’s patients were war veterans. He was the Ministry of Transport doctor for the Maritimes, and among his responsibilities were annual physicals for the air transport pilots who flew for Trans-Canada Air Lines (now Air Canada) and a host of others. Many of these pilots were Bomber Command veterans, with upwards of 50,000 hours apiece in their wartime and postwar logbooks. My dad loved them, for he was an air force veteran himself. His signature blue uniform was stored away in a closet. He rarely talked about the war to me until later in life, but he did wax poetic about the iconic aircraft of the 1939-45 era.

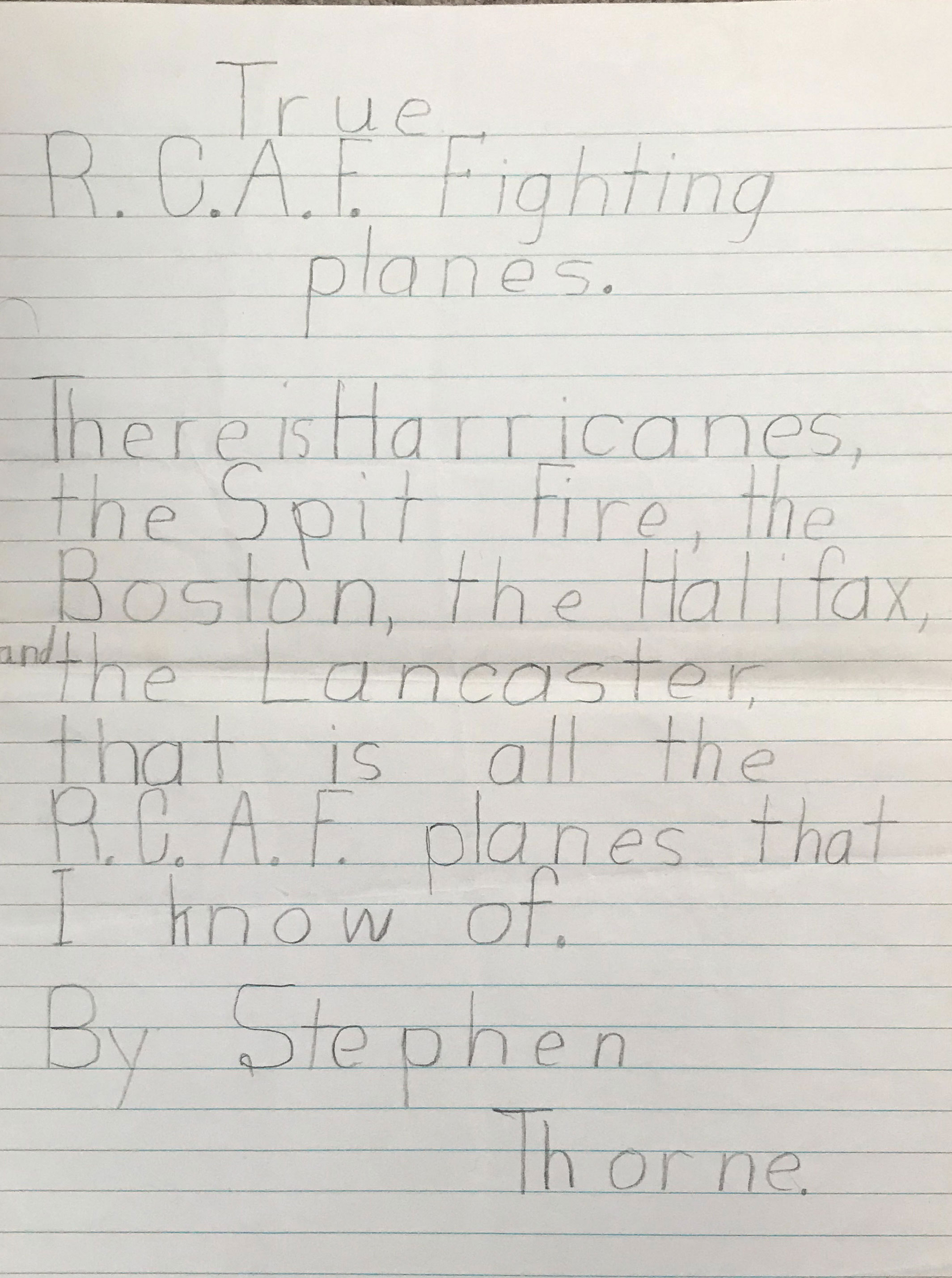

Indeed, the first kit models I ever built, at my father’s behest, were a Hawker Hurricane and a Supermarine Spitfire—in that order, because that’s the order in which they were actually produced.

Truth be told, it was my father who built them, with his typical perfectionism and attention to detail. I watched and handed him the parts. Soon enough, I would learn that I lacked the patience and craftsmanship to assemble a good model—glue would inevitably end up smeared everywhere, decals would get folded and torn and, in the days before airbrushes, the paint was never right.

Stories of Hurricanes and Spitfires were among the first I ever wrote in school, though.

It was TV shows, such as The Rat Patrol, 12 O’Clock High, Combat! and Hogan’s Heroes that fed my passion, along with Sunday documentaries like The World at War and Saturday-morning TV movies on our 1954 21-inch black-and-white Admiral—mainly Hollywood fare from the 1940s and 1950s, such as The Sands of Iwo Jima, Flying Leathernecks, The Cruel Sea and many, many others.

These, of course, were almost exclusively American. Access to anything Canadian, outside of my father’s copy of The RCAF Overseas, seemed woefully difficult.

To me, winter and heavy snow, meant the Battle of the Bulge, the last major German offensive in the west, where bad weather and heavy snowfalls left American troops freezing, undersupplied and surrounded for weeks in the besieged town of Bastogne and the Ardennes Forest of Belgium.

Bundled up in a one-piece snowsuit, boots, scarf, mittens, itchy woolen toque, plastic reproduction M1 helmet and hood, not to mention two pairs of socks, I would waddle my way into the front or back yard to confront Hitler’s 7th Army and 6th Panzer Army.

My parents had bushes around the foundation of the brick house that was the only home I knew growing up. They acted as windbreaks in winter. The snow would accumulate in front of but not behind them, creating a kind of bunker between the bushes and the wall.

I would nestle in there and wait, weapon in hand (as often as not a stick), watching cars pass by, people come and go, conversations happen, or my father shovel the driveway. I would lie still, peering through the bushes, over the snowbanks, a U.S. 101st Airborne soldier scouting German positions in the Ardennes.

Totally absorbed in the fantasy, there was an indescribable excitement around being undetected. My parents, for one, had no idea where I was or what I was doing. It was a different time.

These games were not limited to WW II. Verboten now by a more-informed history and evolved sensitivities, cowboys and Indians was a staple then. The Sioux, the Apache, the Cheyenne, the Iroquois and the Mohawk fascinated me more than the U.S. 7th Cavalry or its equivalents.

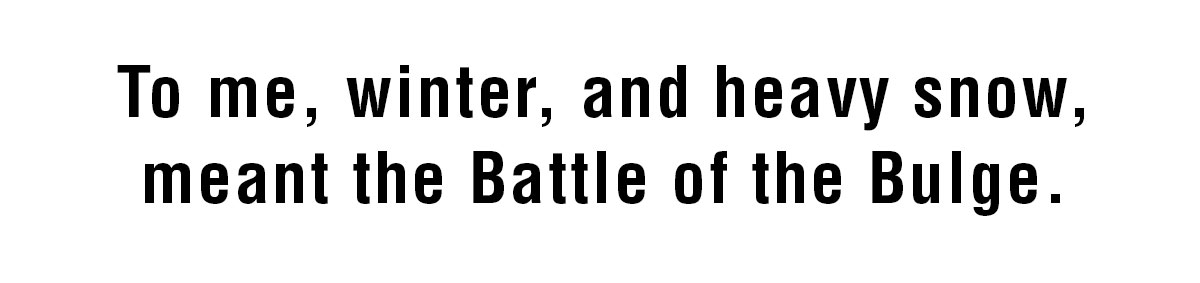

The Philadelphia Chewing Gum Company produced 88 bubble-gum cards featuring WW II photographs, including iconic black-and-white images from the war with informative factual descriptions and backgrounders on the reverse. [Philadelphia Chewing Gum Company]

There is a picture among my father’s slide trays of a very blond me in a navy-blue shirt, the collar pinned up to look like 1860s Union battle dress, a Boston Red Sox cap on my head with the back pushed up and the front crushed down like a kepi of the time. My rifle, as I recall, was a stick. My expression, earnest: War is hell, after all.

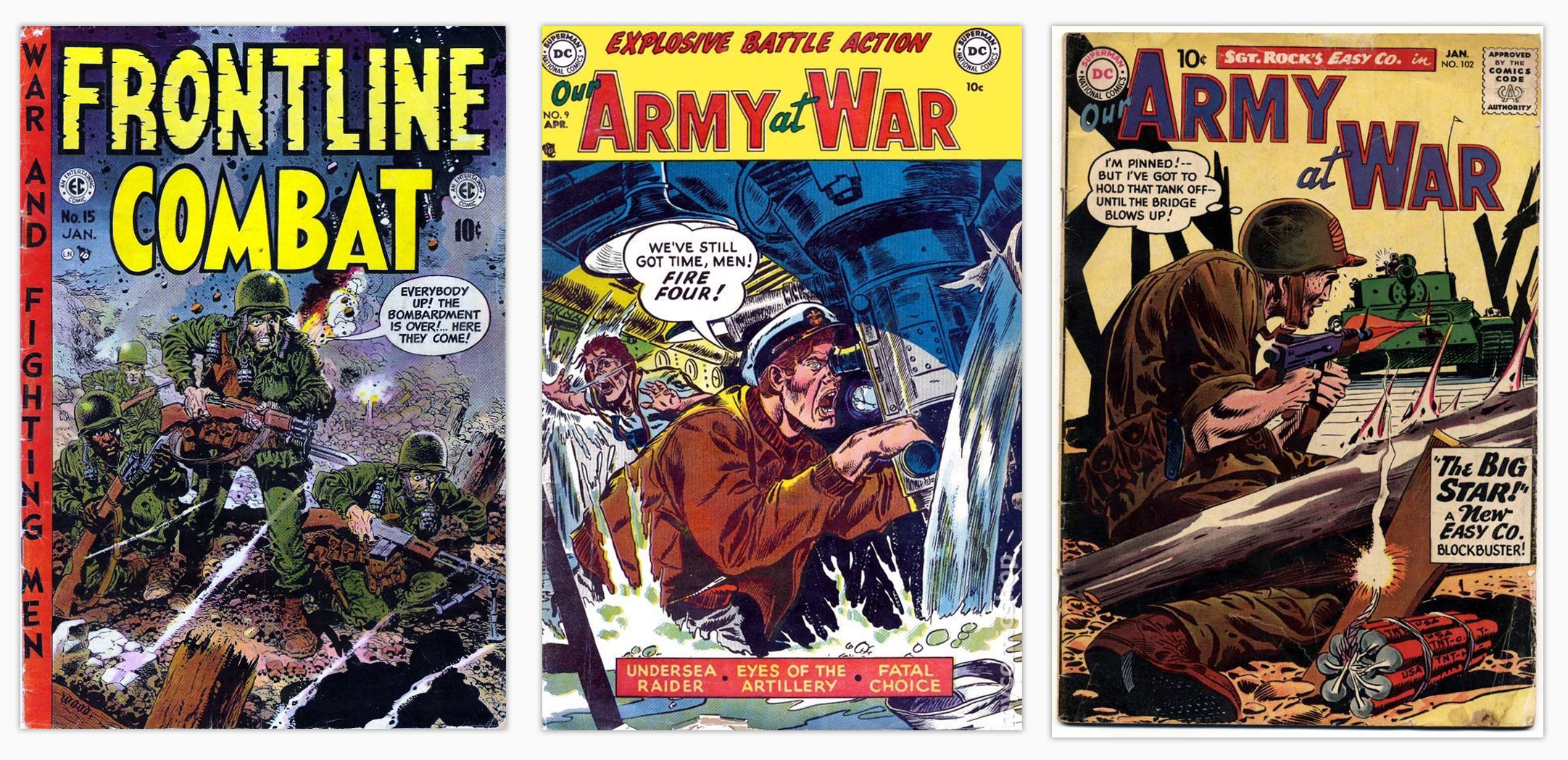

In my room, there were stacks upon stacks of comic books, and trading cards, too.

In 1965, when I was six, Topps produced a series of 66 cards called “Battle: The Story of World War II.” Painted by illustrators Norman Saunders, Maurice Blumenfeld, Ed Valigurski and Bob Powell, the series was notorious for its extremely violent depictions of war, with card titles such as Fight to the Death, Execution at Dawn and Confession By Force, the details of which I will leave to your imagination.

A mint condition Confession By Force currently goes for more than US$200 on eBay. According to the story on the back of the card, incidentally, the French resistance prisoner did not confess, and was freed. So it’s got that going for it.

My personal favourite was a card series produced by the Philadelphia Chewing Gum Company called War Bulletin. The 88 bubble-gum cards were also produced in 1965 and featured WW II photographs—iconic black-and-white images from the war in Europe, North Africa, the Pacific and elsewhere, with informative factual descriptions and backgrounders on the reverse. They were an outstanding chronicle of the war for a young boy.

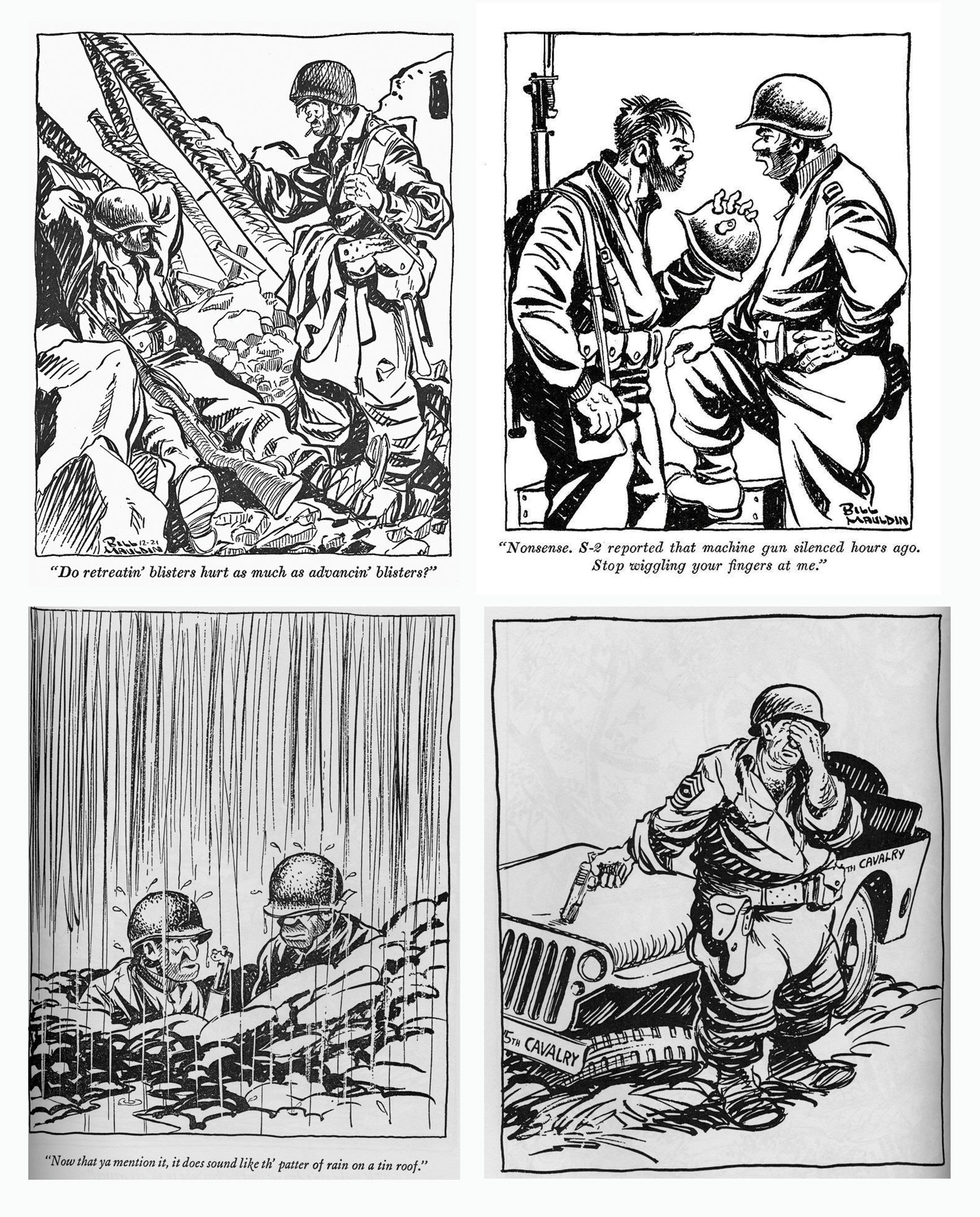

Bill Mauldin’s “Willie and Joe” were icons of the Second World War. Mauldin himself was as a G.I., wounded during the Italian Campaign. His book Up Front is a classic. [Bill Mauldin]

My other favourite was my father’s dog-eared copy of Bill Mauldin’s book Up Front, with its tales of G.I.s Willie and Joe. I would pull it off the shelf and spend hours studying Mauldin’s drawings and absorbing his depictions of wartime life.

All of this took place with the Vietnam War playing in the background like the music of my life. Each week, we’d get Life Magazine, with its graphic photo essays by photographers such as Larry Burrows, Henri Huet and David Douglas Duncan.

Eventually, I found my way into journalism. Now some journalists consider the pinnacle of their trade writing about major league sports; for others it is federal politics; still others aspire to be critics or columnists. For me, covering the dying days of South African Apartheid and Canadian troops at war, which I did in Kosovo and Afghanistan, was destiny.With so much immersion behind me, and 10 years of front-line disaster coverage under my belt, little about the violence and destruction of real-life war surprised me.

Nearly 40 years after those childhood escapades and fascinations, however, the sharp crack of firearms, the rumbling booms of B-52 strikes, the stinging smell of cordite and sickly aroma of death, underscored by the fortitude and resilience of the populace, brought war home and made it very real and sobering.

I went into the experience with curiosity and anticipation, hoping to come to understand the nature of war, what enables people to kill other people, how they function when confronted with those stark realities, and how the innocents live under the stresses of lives in war.

I definitely wanted to tell a good story. I suppose, too, a part of me wanted to show myself that that young kid who played at war so devotedly and so innocently could, to the degree that my trade demanded, walk the walk.

Watching a Canadian soldier crawl into a suspected Taliban cave with nothing but a sidearm and a penlight and emerge minutes later in one piece, and following Canadian and American troops as they swarmed an enemy cave and bunker complex with abandon, were among the most inspiring things I have witnessed.

But I was just as impressed by the everyday people I met, who lived whole lives—in many cases, short ones—with these stresses surrounding them, and by the fact that many wars now and in the past are not clearly matters of right and wrong, that the “good guys” aren’t always the good guys, and that they don’t always win.

I walked the walk, all right. I faced down fear, absorbed the pain, and did my job, which wasn’t to fight but to tell the stories of those who fought. I look out the window now and it’s a sea of white. It’s peaceful. And I am very, very grateful.

There are more stories to write, and miles to go before I sleep.

Advertisement