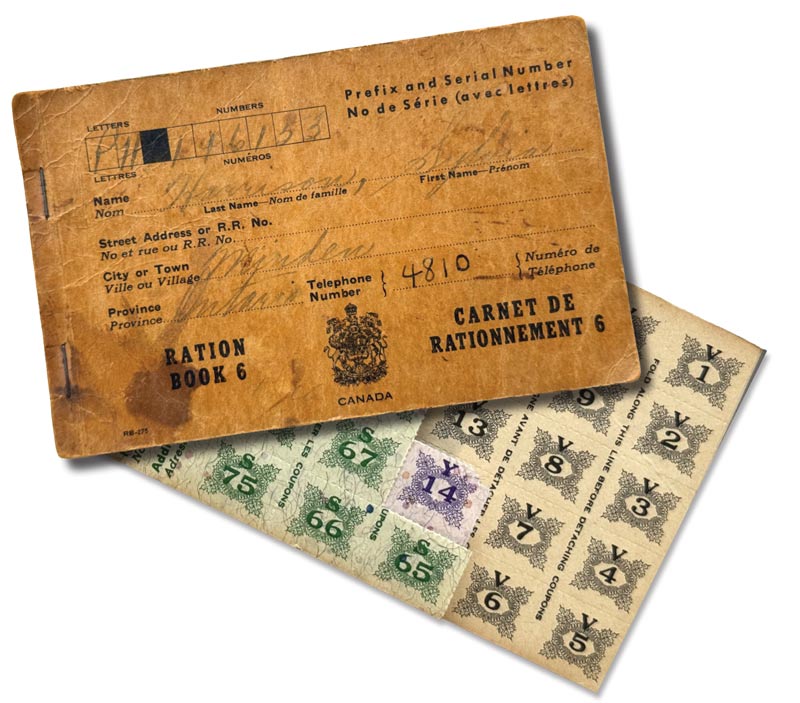

Ration Book 6 circa 1946. Like the entire series, it included coupons for limited resources such as butter. Meat tokens were introduced in 1945. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

After Britain was cut off from European supplies in 1940, her people and her fighting men were saved from starvation by Canadian food,” declared Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King in a September 1942 radio address.

Certainly, Britain’s plight had galvanized citizens across the agricultural Dominion. Food production had thus accelerated to support the Empire and Canada’s own armed forces, heeding the age-old axiom that an army marches on its stomach.

By war’s end, Canadian exports to the U.K. accounted for some 57 per cent of British wheat and flour—having peaked at 77 per cent in 1941—39 per cent of bacon rashers, 24 per cent of cheese, 15 per cent of eggs and 11 per cent of evaporated milk. It did, however, come at a cost for Canadians at home.

“The war effort made people hungry,” explained the Canadian War Museum’s military historian and wartime agricultural expert Stacey Barker. “We needed more food—and we needed that food to be distributed as equitably as possible.”

The federal government began with requests for citizens to voluntarily limit their consumption of scarce items, including sugar. “That’s the first commodity Canada rationed in January 1942,” said Barker, “as about 80 per cent of sugar was imported—a significant amount of which came from Japanese-controlled areas in the Pacific.”

When the honour system failed to produce the desired results, the Wartime Prices and Trade Board implemented coupon rationing. During the ensuing months and years, not only sugar but tea, coffee, butter, preserves and certain meats were restricted. Gasoline was also conserved, creating issues in transporting non-rationed goods.

When the honour system failed to produce the desired results, the Wartime Prices and Trade Board resorted to coupon rationing.

Despite this, noted Barker, “Canada got off lightly compared to Britain.”

After a brief period of using temporary ration cards, authorities distributed an estimated 11 million ration books—the first of six series—in August 1942.

[CWM/19740096-012; CWM/19920196-138]

“Ration Book No. 1 was a pocket-sized booklet with your name on the cover and coupons inside for various commodities,” continued Barker. “The different colours depended on the commodity, so red for sugar, green for tea and coffee, and there were blue, brown and black coupons that officials assigned to goods as needed.

“Canadians would visit a store to purchase sugar, for instance, and the retailer would detach the requisite number of coupons when they made the purchase, which couldn’t exceed more than one pound or a two-week supply of sugar.”

Successive ration books, all broadly similar in appearance, were printed to reflect the fluctuating availability of foodstuffs as the war progressed.

Of course, abundance didn’t miraculously return on VJ-Day, with some measures persisting into the postwar period. When Ration Book No. 6 was introduced in 1946, Canadians had grown weary of the shortages, even if items such as eggs, flour and chicken were never restricted. Rationing officially ended in 1947.

“Canada didn’t suffer the same fate as many parts of the world,” said Barker. “Our cities, for one, weren’t flattened by bombs. Rationing in the country, along with all the rules and regulations—and there were tons of them—amounted more to a mild inconvenience than that which befell other nations. Canadians, though not always in lockstep, generally perceived rationing as a common cause for the war effort.”

Advertisement