A Royal Air Force Halifax bomber flies over Germany’s Ruhr valley in a raid on oil facilities.[ Alamy/JNXR5N]

Crack teams of navigators and pilots marked targets from the air, in the dark and under fire

At the beginning of the Second World War, when Germany learned it would never persuade Britain to remain neutral or sign a peace treaty, sterner measures were adopted. The Nazis decided try to bomb and starve Britain into submission.

The Luftwaffe attacked industrial targets while the Kriegsmarine went after the island nation’s supply lines. An army invasion was planned as the next step.

But attacking Britain while fighting the war on other fronts would take all of Germany’s industrial might—coal for industrial furnaces, steel for ships and aircraft, raw materials for munitions and factories to make them, railways, highways and canals to move supplies, troops and materiel, as well as fuel processing facilities to power vehicles.

Royal Air Force Bomber Command, Britain’s only means at the time of taking the fight into Germany, was tasked with destroying as much of that as possible.

Target markers had names as colourful as their glow— Red Blob and Pink Pansy.

At first, Britain’s bombing campaign was a dismal failure.

An Avro Lancaster flies through flak tracers in a bombing raid on Hamburg.[Getty Images/90780466]

It began with daylight raids against military targets—warships and airfields. But when the Netherlands capitulated after Rotterdam was reduced to rubble in May 1940, Bomber Command was ordered to attack German targets in the Ruhr

valley, Germany’s industrial heartland.

Targets in Europe were well-defended, turning daylight raids into suicide missions, so Bomber Command moved to night attacks. But technology for night navigation was primitive.

Early in the war, navigation for bombing raids was a hit-or-miss affair, the emphasis on miss. While heading for targets on the continent, navigators would climb into a Perspex bubble on top of the aircraft, take a half-dozen timed photos of the stars, then go to the navigation charts to work out where the aircraft was.

“If you were lucky,” said navigator James McCloy in a 2003 documentary, The Men Who Lit Up Germany. It was “the sort of thing that mariners had been doing for years,” but ill-suited for precision bombing by fast-moving aircraft. “On the ground I found the best I could do was fix the position of the aerodrome within five miles [eight kilometres]. In the air, I’d have been lucky if I’d gotten 20.”

Before navigation aids, crews had to rely on dead reckoning—estimating their position by aircraft and wind speed, flying time and compass. Calculations were easily disrupted by wind.

Germany. Air Vice Marshal Don Bennett commanded the Pathfinders. [ Wikimedia]

An examination of bombing in June and July 1940 showed only one in three British bombers got within eight kilometres of their targets; over the Ruhr River, it was one in 10. With no moon, the figure dropped to one in 15. In the year ending May 1941, it was found that 49 per cent of bombs had fallen in open country.

It is one thing to navigate over foreign territory during the day and “quite different doing it in a heavy bomber, at night, under total blackout conditions, sitting above 9,000 or more pounds [4,000 kilograms] of bombs and flares, over unfamiliar and hostile territory, while being shot at from the ground or attacked by enemy fighters,” recalled navigator Donald M. Currie of North Vancouver, B.C.

Precision bombing was simply impossible given the limitations of technology and lack of experienced crew—in 1940 many navigators didn’t get much time to gain experience. Royal Air Force bomber crews, which included many Canadians, were lost faster than they could be replaced.

Success lay in the development of better technology to help aircraft fix their positions and find their targets—and better attack techniques.

One of those techniques was marking targets from the air.

Fire ravages a German aircraft plant bombed late in the war. [Wikimedia]

Bomber Command navigators and pilots with the best records for accuracy were cherry-picked for a crack unit—No. 8 (Pathfinder Force) Group—whose job was to fly ahead of a main bomber formation to drop flares to mark targets and illuminate the way for bombers. The Pathfinder Force, numbering about 20,000 men (and women, in ground jobs) was commanded by Air Vice Marshal Don Bennett, an Australian described as an outstanding pilot and superb navigator equally capable of stripping a wireless set or overhauling an engine.

Pathfinder crews led 51,053 sorties, flying Halifax, Lancaster, Stirling, Wellington and Mosquito aircraft with the best crews and up-to-the-minute technology continually upgraded throughout the war.

Over the course of the Conflict, the British pioneered external navigation systems that used precisely timed radio signals to allow navigators to fix their positions and ground-scanning radar to identify targets at night and in bad weather.

Beefed-up fireworks produced brilliant white flares for illumination and target markers with names as colourful as their glow—Red Blob and Pink Pansy. Rear-facing aerials (called Boozers) warned the pilot when aircraft were being monitored by enemy radar.

Bombs pour from an Avro Lancaster on a thousand-bomber raid over Duisburg, Germany, in October 1944.[Wikimedia ]

The Pathfinders’ first operation on Aug. 18-19, 1942, was not a success, as winds caused the aircraft to drift north and targets were incorrectly marked. The second foray was little better.

But at the end of the month, Pathfinders came into their own in a raid on Kassel, Germany, marking targets for 306 bombers that destroyed 144 buildings and damaged more than 300, including three aircraft factories. Their record improved from there.

Led by Pathfinders, bombers came within five kilometres of targets 73 per cent of the time during the Ruhr campaign in 1943 and by the end of the war that record had improved to 95 per cent, said Will Iredale, author of The Pathfinders: The Elite RAF Force that Turned the Tide of WW II.

“Pathfinders would drop flares and identify the target, then others would drop coloured flares on each side and we would fly between the flares,” recalled Joseph (Jo) Forman in his memoir on the Canadian Letters and Images Project website. “We had three minutes leeway at each turning point and over the target,” said Forman. “Naturally we did a lot of pastoral bombing.”

Currie volunteered for Pathfinder training, attracted by the challenge of navigation. “They used two navigators rather than one and the attrition rate was much higher than the main force, so we might be called earlier.”

Currie was assigned as navigator/observer to No. 635 Squadron, RAF. Five of eight crew on his first operation were Canadians, including the wireless operator, two gunners and the pilot, Len Moore of Niagara Falls, Ont., who had already completed one operational tour with Bomber Command.

Currie was teamed with a British navigator/plotter. “We operated in a completely blacked-out compartment,” working by weak lamplight and the glow of equipment. “We sat side by side on a narrow bench and unless we made an effort to pull the blackout curtain…we saw nothing but our instruments for hours on end.”

New Pathfinder crews were broken in slowly, starting out in a support role carrying the same bomb load as the main force.

“Exceptional standards had to be met before a crew could qualify for the next step,” Currie recalled. Once they had proved themselves, crews undertook more and more demanding marking duties.

In June 1943, Bomber Command tested very-high-frequency radio equipment that allowed communication among aircraft in attack formations. This allowed a lead Pathfinder, which became known as the master bomber, to alert other Pathfinders to re-mark targets when the first flares drifted off course, and to radio corrections to bombers.

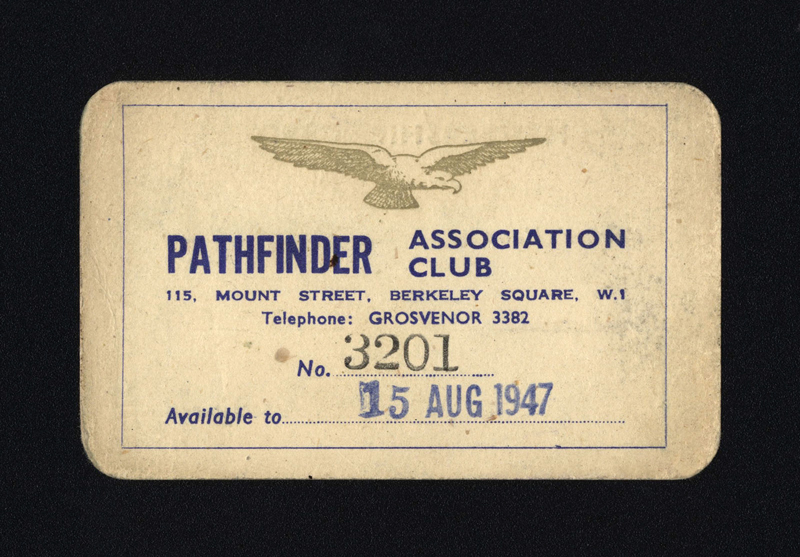

Charles Godfrey was issued this membership card when he joined the Pathfinder Association Club after the war; master bomber Ian Willoughby Bazalgette died trying to save fellow crew members. [ M. Godfrey/International Bomber Command Centre]

It was one of many tweaks to attack techniques. Enemy airfields were attacked prior to raids to dilute the available fighter force. Enemy radar was jammed. False intelligence about raids was leaked to the enemy and feint raids on nearby towns drew fighters away from main targets. Bits of aluminum and other material (called window or chaff) were dropped in clouds to swamp readings on enemy radar.

The first Pathfinders arrived over targets two to six minutes before the main force, dropping illuminating flares and releasing barometric markers that would go off at different altitudes and drift downwind. But there were other Pathfinders within the mass of aircraft to continue marking the target, as flares and target indicators had short lifespans and could be blown off course.

Precision bombing was simply impossible

“It’s a dangerous job,” William Douglas Watson wrote home to his family in May 1944, “but you have all the tops in equipment and crew. Advancement is really fast too.”

The letter did not tell them why—the survival rate was grim.

Only 16 per cent of Bomber Command crews survived their tour of 30 operations. To make the most of their extra training, Pathfinder crews, many of whom had already completed one Bomber Command tour, signed on for 45 operations (which had been reduced from 60 to encourage volunteers).

“Each man got an immediate promotion in rank and a pay rise—danger money,” wrote Iredale. “And they earned every penny of it. Over the next three years, 3,600 were killed in action. An individual Pathfinder would be lucky to still be alive after 12 sorties. The loss rate was so great that 50 new crews had to be recruited every month.”

Flak and enemy fighters were a constant danger, but so was equipment failure.

“One thing that airmen can never overlook in weighing the scales of survival is Lady Luck,” said Flight Lieutenant Bill Davies, a navigator who settled in Toronto after the war, quoted in Jean Portugal’s We Were There.

On a clear night in February 1945, his crew was off the coast of Sweden, returning from marking a mission to bomb an oil installation.

“The mid-upper gunner shouted there was a Ju 88 sitting out on the starboard beam with his cockpit light on. It was so plain to see and so easily recognized.” It was also a ruse readily recognized by gunner Michael McCrory of Hamilton, Ont.

McCrory started advising the pilot to corkscrew and “warned us to watch out for a Ju 88 friend who would sneak up behind, completely blacked out, and open fire. And that’s what happened.”

They were hit, “but the discipline of the crew was excellent.” Skill got them to the safety of cloud cover, despite the loss of two engines. Then a third engine failed.

“We had to get back to base on one engine.” They slowly descended to an altitude of 150 metres—and heading down—when they were still 650 kilometres from England. The pilot prepared to ditch the plane in the North Sea, at its most unforgiving in winter. Davies shook hands with his friend, navigator George Blick.

“All we had on was ordinary shoes in the Nav section and a simple sweater and battledress, Mae West [life preserver] and parachute, and a helmet and oxygen gear and two pair of gloves. So we weren’t going to last very long.”

Suddenly the dead engine started on its own and was nursed back to life by the

captain and engineer. “We managed to get home on two engines.”

Getting hit by bombs from their own group was another danger.

“We were all supposed to fly at specific height, but many crews decided they would fly higher” to avoid mid-air collisions, recalled Davies, whose crew was horrified to see a Halifax barrelling toward them in January 1945.

“We screamed…and managed to dive, missing this aircraft by a few feet. A huge bomb, possibly a 4,000-pound [1,800-kilogram] cookie, just missed us in front. The skipper pushed the stick forward and the Halifax skimmed over the top of us. We could only suppose [this pilot] was very, very late and had cut a corner.”

And that wasn’t the only time they saw bombs cascading past them, he said.

It wasn’t unusual for strong winds to blow bombers off course, as happened to Ed Moore’s crew on a raid on Berlin.

“It became obvious when Pathfinder flares went off behind us that the actual winds were very much stronger,” the veteran of 26 missions said in an Edmonton Journal interview in November on his 100th birthday.

“We turned around and dropped our bombs on target about 25 minutes late. Common sense should have dictated the bomb be jettisoned and a course set for home. Nevertheless, we all agreed with our skipper-pilot who said, ‘We have come this far, we will drop the bombs in the right place.’”

Pathfinders were first to arrive at targets, where they were the focus of searchlights of ground defence crews. Master bombers faced the most danger. Their job was to circle the target, co-ordinate the attack, and broadcast instructions to other aircraft. They remained over the target longer and their radio transmissions could be tracked by defences and night fighters.

“It was when the master searchlight got you that you knew you were in trouble,” recalled Wing Commander A.J.L. Craig, who flew 73 operations, 41 as master bomber. “All the other searchlights would point at you, and then every gun in the area would take aim.” It was known as being ‘coned’ and pilots had a devilish time escaping.

“The good side to it was that most of the other bombers nearby would get a free run and thank you later, if you made it back to base. The reality was that most people who were coned were shot down.”

“Each man got an immediate promotion in rank and a pay rise—danger money.”

In April 1943, No. 405 (City of Vancouver) Squadron joined the group—the only Royal Canadian Air Force unit in the Pathfinder Force (although Canadians served in every squadron).

Bennett was opposed to differentiation within the force and had already refused a request for the formation of an Australian squadron.

“I insisted that the crews of this so-called Canadian squadron must not be more than 50 per cent Canadian, [but] I did agree that the CO would always be a Canadian, and it started off under the command of Wing Commander [John] Fauquier, a thoroughly ‘press-on’ type if ever there was one,” wrote Bennett.

John Fauquier of Ottawa had been a bush pilot before the war and had already completed 35 bombing operations before taking command of 405 Squadron in February 1942. He was a hard taskmaster, but many considered him Canada’s greatest bomber pilot.

On Aug. 17, 1943, Fauquier was deputy master bomber during a raid on a German rocket base on the Baltic coast, passing over the target 17 times, guiding bombers. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for that operation, which delayed the use of the rockets by a year.

When he retired in 1944, after flying 38 sorties as a Pathfinder, he was awarded a Bar to the medal and a promotion to commodore.

Retirement didn’t suit Fauquier. He requested his rank be lowered so he could fly a third tour of operations. He went on to No. 617 Squadron, RAF—known as the Dambusters—where he earned a second Bar to his DSO.

Fauquier was one of many notable Canadian Pathfinders.

Reg Lane of Victoria received a Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) following 30 sorties on his first Bomber Command tour, during which he attacked the German battleship Tirpitz at mast height. He remained with No. 35 Squadron, RAF, when it was selected to join the Pathfinders.

On the final run of his second tour in April 1943, Lane was coned over Frankfurt, escaping the searchlights and anti-aircraft fire with a steep dive of more than 300 metres. He was awarded the DSO.

John Fauquier commanded 405 Squadron[LAC/PL-10408]

After a four-month break from operations, Lane returned to the sky, taking over command of 405 Squadron from Fauquier. He often served as master bomber, notably circling the city while under fighter attack for 40 minutes during the Battle of Berlin.

In May 1944, Lane was awarded a Bar to his DFC on a raid to Caen, France, as master bomber on his 65th mission just prior to D-Day. After his third tour, Lane went on to operational tactics, rising to lieutenant-general after the war and serving as deputy commander-in-chief at Norad before retiring in 1976.

Squadron Leader Ian Bazalgette of Calgary was one of three Pathfinders to earn the Victoria Cross. On Aug. 4, 1944, on his 58th mission, he was master bomber in a daylight raid on a V-1 storage cave near Saint-Maximin, France. His Lancaster was hit by flak before arriving at the target.

The aircraft ablaze, two other master bombers out of commission, Bazalgette continued on to mark the target, then ordered the crew to bail out. He fought to land the burning aircraft in order to save two wounded crew and avoid crashing in the village of Senantes.

Wireless operator Chuck Godfrey bailed out and watched the bomber go down.

“I could see it all,” said Godfrey, quoted on the Bomber Command Museum of Canada website. “He did get it down in a field…but it was well ablaze and with all the petrol on board it just exploded.” The three still on board were killed.

Bazalgette was one of 10,000 Canadians killed serving with Bomber Command. Fifty-five thousand Allied men and women lost their lives serving in the bomber forces. Pathfinder crews were well aware of the risks.

“On the walks out to the trucks that used to take us to the pads where the Lancs were sitting, you’d see one or two vomiting like mad,” recalled Davies. “They were the bravest of the lot. They really were so frightened they had almost no control. But they went.

“There was a widespread feeling of pride…morale could not have been higher. The mere thought of going back to the main force was seen as almost the end of the world.”

The Pathfinders’ contribution to the end of the war is incalculable. They improved bombing precision and allowed Bomber Command to increase the intensity of raids and to destroy many targets in a single raid on one city. Raids on the Ruhr valley alone resulted in declines of metal processing by 46.5 per cent in 1943 and 39 per cent in 1944.

More importantly, the bombing campaign opened a second front long before D-Day, said Albert Speer, German minister of armaments and war production.

“Defence against air attacks required the production of thousands of anti-aircraft guns, the stockpiling of tremendous quantities of ammunition all over the country, and holding in readiness hundreds of thousands of soldiers, who in addition had to stay in position by their guns, often totally inactive, for months at a time.”

Not only did the Axis lose factories and war materiel, but huge numbers of troops and labourers were tied up defending against bomber raids and rebuilding afterward. Speer called the air war “the greatest lost battle on the German side.”

Advertisement