WAR SHAPED CANADA. Those three words do not often occur to Canadians living in our peaceable kingdom, but they are surely true. The future of British North America was decided on the Plains of Abraham in 1759 and confirmed during the War of 1812 in which the Canadas barely survived American invasion. Two great world wars demonstrated that Canada would exert itself to the maximum to defeat the expansionist aims of Kaisers and Axis dictators. And the war in Afghanistan saw Canada deploy its men and women into action to battle extremist Islamists who could—and did—threaten the democracies. Canada was no great power, but its servicemen and servicewomen over the last century have played major roles in war in concert with their allies.

Artist Hervey Smyth combines all aspects of the battle into a single painting. [Peter Winkworth Collection of Canadiana/LAC/R9266-2102]

WAS CANADA TO BE A FRENCH OR BRITISH COLONY? The Seven Years War (1756-63) decided that question, and the key battle was fought at Quebec on Sept. 13, 1759. That engagement pitted General James Wolfe and his British regulars against the Marquis de Montcalm and his larger but mixed force of regulars, First Nations warriors and militia. The preliminaries to the decisive engagement had been lengthy; the battle on the Plains was to be very brief.

James Wolfe, born in 1727, had been an army officer since 1741 with service on the Continent, in Scotland, and in the taking of Louisbourg in 1758 where, as a brigadier, he distinguished himself. To Wolfe’s surprise, he received command of the land forces for the expedition against Quebec on Jan. 12, 1759, and was promoted to major-general. His command encompassed some 10 battalions of infantry, in all some 8,500 capable regulars. The expedition had the support of 49 ships, including 22 men-of-war with 50 or more guns.

Wolfe was ill with stomach complaints and rheumatism and, although a highly capable officer, he had difficulty managing his subordinates. Almost from the time the expedition set sail from Louisbourg for Quebec on June 4, 1759, Wolfe and his three brigadiers disagreed on almost everything.

On his arrival off Quebec on June 27, Wolfe’s initial plan was to land east of Quebec on the north shore of the St. Lawrence, but Montcalm had anticipated this tactic and fortified the shore. The British commander, confident that if he could force Montcalm to stand and fight he would win, thus found himself forced to revise his planning. If he could not force the French to fight, winter would force Wolfe to retreat to Louisbourg until the late spring of 1760.

What to do? Wolfe kept changing his plan, his ill-health compounding matters. He emplaced cannon opposite Quebec and shelled the town; he launched an attack just west of the Montmorency River on July 31 and suffered heavy losses; and he ordered the burning of settlements east and west of Quebec. Finally, unable to decide on his course, he wrote to his three brigadiers and asked them to “consider the best method of attacking the Enemy.” Wolfe’s subordinates suggested that the army direct operations above the town on the north shore of the great river. Sitting astride Montcalm’s lines of communication to Montreal and the interior of New France, they said, “the French General must fight us on our own Terms….” Wolfe agreed, and on Sept. 8 or 9, he reconnoitered down river and decided to attempt a landing at Anse au Foulon where a track led up the cliffs. The rest is history.

At 4 a.m. on Sept. 13, several companies of light infantry scaled the cliff and drove off the small French force at the site. By morning, Wolfe’s regulars were drawn up in line on the Plains of Abraham, and Montcalm, who might have awaited reinforcements coming from the west, instead decided to fight. He came out from Quebec, formed his columns, and launched his men at the British lines at 10 a.m. Wolfe let the French come to within 40 yards, and two heavy volleys destroyed them. In the 15-minute battle, Montcalm was severely wounded and carried back to Quebec where he died. Wolfe, hit three times, died on the Plains. The remainder of the French force soon headed west, moving around the British. The town of Quebec surrendered on Sept. 18.

The conquest of New France was not yet complete. The Royal Navy had to leave the St. Lawrence soon after the victory, and the British garrison, ravaged by scurvy, struggled to survive. In late April 1760, the French attacked and won a substantial battle at Sainte-Foy, just west of Quebec, but the British withdrew within the walls of the town. Overall success now depended on the arrival of supply vessels—if French, New France might well survive; if British, the colony was doomed. In mid-May, the Royal Navy arrived, and the conquest was effectively complete. Montreal capitulated in September, and the Treaty of Paris in 1763 gave New France to Great Britain.

The French fact remained in Canada, but the colony’s future now was in London’s hands. Wolfe had not been a great commander, but he had won the decisive battle, his outnumbered regular soldiers defeating the mixed French force. The fate of empires, the destiny of Canada, had depended on a track up the cliffs at what is now known as Wolfe’s Cove.

Major-General Isaac Brock’s dying words were, “Push on York Volunteers!” [John David Kelly/Beaverbrook Collection of War Art/CWM/19970051-001]

THE WAR OF 1812 POSED AN EXISTENTIAL THREAT TO BRITISH NORTH AMERICA. Could the Canadas survive an assault from the numerically superior, richer United States? To do so would take strong leadership, and fortunately at the beginning of the war in June 1812, the British forces had such a leader in Major-General Isaac Brock.

Brock faced a formidable task in planning the defence of Upper Canada. Many of the settlers who had arrived in the last 30 years had come from the United States; outnumbering Loyalist settlers by at least four to one, their loyalty was naturally suspect. The legislature was unco-operative, unwilling to make serious plans for war. British regular troops numbered only 1,600. And the loyalty of the First Nations hinged on demonstrating that the British defenders had a credible chance of victory. Brock knew he had to strike first.

Immediately after he learned that the war had begun, and after some uncharacteristic vacillation, Brock ordered Captain Charles Roberts at Fort St. Joseph, at the head of Lake Huron, to seize Michilimackinac. Roberts moved 600 men—natives, a few soldiers, and some fur traders—the 80 kilometres to Michilimackinac, told a surprised U.S. commander that war had been declared, and quickly accepted his surrender on July 18. The small victory put the First Nations of the upper Great Lakes with the British.

More was to come. On July 12, Brigadier-General William Hull led American forces from Detroit into Canada. Militia along the frontier deserted to the Americans or fled. Brock was discouraged, worried that public morale was low, everyone fearing that Upper Canada was doomed. But British troops still held Fort Amherstburg, and Brock gathered regulars, natives, and militia and reached Amherstburg on Aug. 13. He found that Hull, a pompous, weak commander, had already returned to Detroit with his 2,000 men. Brock understood, as he said, that “the state of the Province [of Upper Canada] admitted of nothing but desperate measures.” The Provincial Marine had captured a U.S. vessel with General Hull’s correspondence to the Secretary of War in Washington. It was clear, Brock said, that “Confidence in [General Hull] was gone and evident despondency prevailed throughout.”

Brock’s cool calculation led to his decision to attack Detroit. On Aug. 16, he moved his force of 1,300, including 600 First Nations warriors led by the Shawnee chief Tecumseh and 400 militia across the Detroit River, and invited Hull to surrender. The threat of the First Nations becoming “beyond control the moment the contest commences,” as Brock wrote Hull, did the job, and the U.S. general capitulated, surrendering his men, his supplies, and his 35 cannon and other weapons.

The effect of Brock’s bluff and boldness on the Upper Canadian population was quickly evident. Brock wrote his family that “The militia have been inspired by the recent success with confidence—the disaffected were silenced.” No one any longer thought a British defeat inevitable.

The war was far from over, however, and Brock himself was killed in the first major battle on the Niagara Peninsula, the victory at Queenston Heights in October 1812. The defenders of the Canadas would not always be as well led in the future as they had been by Brock, but the overall stalemate in the two-year-long war meant that the Canadas, simply by surviving, had won a great victory. They had remained in British hands, and American expansionism had been checked. Brock was and remained the hero of the war, the able, charismatic leader who understood the impact even small victories could have on public opinion.

A HUNDRED YEARS LATER, THE DOMINION OF CANADA WAS AT WAR AGAIN. The relation-ship with the United States had been improving for decades, despite occasional war scares. Canadians had fought the Boers in South Africa at the turn of the century, but the population was completely unready for an overseas conflict.

The Great War began for Canada the day Britain declared war on the Kaiser’s Germany; Canada was a colony and was at war when Britain was at war. Men rallied to the call at once, and continued to do so until casualties outpaced volunteers in late 1916. Mainly recent British immigrants, the Canadian troops that went overseas learned on the job. They held against the first major gas attack at Ypres in April 1915. They fought on the Somme in 1916, they took the hitherto impregnable Vimy Ridge in April 1917, and they slogged through the horrors of Passchendaele in the cold of autumn, 1917. Their most crucial battles—the Hundred Days from Aug. 8, 1918, to the Armistice—were yet to come.

In Aug. 1918, the Canadians led a major attack at Amiens, advancing up to 15 kilometres on the first day. By now led and staffed by Canadians, its soldiers almost half Canadian-born, the Canadian Corps had a well-earned reputation as a corps d’élite, and Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Currie, the General Officer Commanding, was admired by the British high command. Sadly, Currie was not loved by his own troops.

After Amiens, the Canadians’ four divisions moved north to Arras. The troops were at full strength and, thanks to Currie, had more engineers, more trucks, more guns and more infantry than any British corps. In a series of costly struggles, the Canadian Corps cracked the Drocourt-Quéant Line, forced a German retreat, and moved west toward the unfinished Canal du Nord. To get across was their task, the most critical of the war.

But how? The banks were high, the canal wide, with the German side well-fortified. Enemy machine- gun posts dotted the bank, there were successive trench lines to the rear, as well as guns and gas. Currie did his own reconnaissance, as he always did, and decided that the best place to attack was a 3,600-metre unfinished stretch of the canal. To succeed, he needed the element of surprise, and to send 50,000 men through a narrow gap and fan them out to a 15-20 kilometre frontage. He would require quickly constructed bridges able to handle tanks and trucks, good communications, and enough ammunition, wire and food to sustain his troops against enemy counterattacks. The plan, produced by Currie’s almost wholly Canadian staff officers, was complex, but well-prepared.

His British superiors were dubious that Currie could carry out his bold plan. “Old man,” his friend General Sir Julian Byng asked, “do you think you can do it? “Yes,” Currie replied. “If anybody can do it, the Canadians can.” Byng rejoined, “but if you fail it means home for you.”

The Canadian guns opened up in the early hours of Sept. 27, and the infantry of the 1st and 4th divisions moved out. The Canadian Engineers quickly provided bridges for the infantry and ramps for the guns and vehicles, getting all over the far bank. The 4th Division got caught in enfilade fire but nonetheless cleared Bourlon Wood, its objective. The First Division, swinging left, cleared villages alongside the canal. The front now approximated 15 kilometres, and the 3rd Division and a British division crossed the canal. The enemy rushed up reinforcements, and the fighting continued until Currie called off the advance on Oct. 1. The road to Cambrai, the major road, rail and supply point for the Germans in northern France, now beckoned.

Currie’s Canadians were now in the midst of what later became known as The Hundred Days. The Canadians would smash the German positions on the western front and crush one-quarter of the enemy divisions in the field. Between Aug. 8 and the capture of Mons, Belgium, on Nov. 11, Currie’s four divisions played the most important battlefield role ever by Canadian soldiers. The cost was terrible—45,000 killed, wounded and captured, or 20 per cent of the total Canadian casualties in the 1914-18 war—but the territorial gains and the blows dealt the enemy were real and hugely important. The German aim of controlling Europe had been checked by the Allies, and the Canadian Corps had played a disproportionate role.

The Canadian Corps had demonstrated that the untrained civilians of 1914, now turned into proud Canadians by battlefield success, could become the skilled, technically competent and fierce soldiery of The Hundred Days. They had shown that they could learn to fight well on the job, build a great reputation and achieve renown. And Sir Arthur Currie had become Canada’s greatest soldier, a commander who was fertile in imagination, cared for his men and ranked among the very best of The Great War.

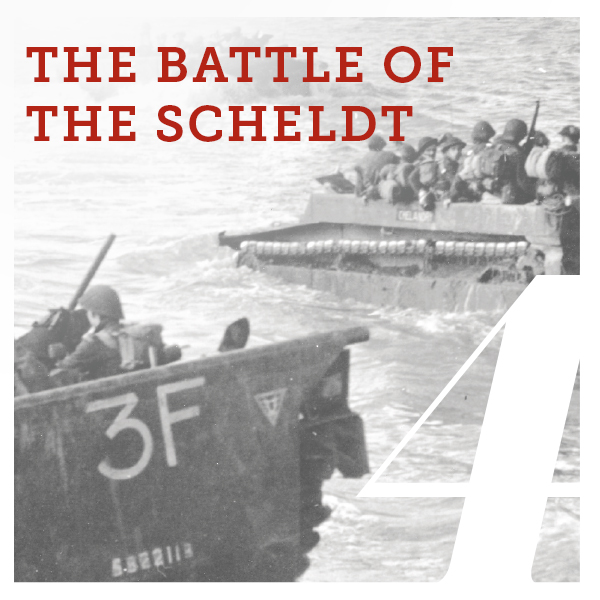

Buffalo amphibious vehicles carry Canadian troops across the Scheldt River, Oct. 13, 1944. [Donald I. Grant/DND/LAC/PA-136754]

SADLY, THE LESSONS OF THE GREAT WAR WERE QUICKLY FORGOTTEN IN CANADA. Governments allowed the armed forces to dwindle to almost nothing, the weapons soon became obsolete and once again Canada would fight a war from a standing start.

Canada went to war on Sept. 10, 1939, not as a colony as in 1914, but as a dominion in control of its domestic and foreign policy. Still, Canada went to war against Hitler’s Germany because Britain did. And as the war went on, as Britain suffered defeat after defeat, Canada’s primary effort was to build a First Canadian Army of five divisions and two armoured brigades in Britain. In 1943, first one, then two divisions went to fight in Italy. The remaining three divisions crossed the Channel to France in June and July 1944, participating in the fierce fighting in Normandy and the breakout in August. The First Canadian Army formed a substantial part of the Allied effort against the Nazis.

By the end of September, the Army’s II Canadian Corps was in Belgium preparing for its major struggle of the war. Lieutenant-General Guy Simonds, the corps commander, had temporarily replaced General Harry Crerar, ill with serious stomach problems, as Army commander. His task was to clear the Scheldt estuary—somehow forgotten by 21st Army Group’s Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery—so that desperately needed supplies could reach the great port of Antwerp, captured intact by the Allies but 80 kilometres inland.

The Germans had been beaten badly in Normandy, but they had recovered with amazing speed and were fortifying the South Beveland Peninsula and Walcheren Island. Getting them out would be the hardest task of the Second World War for the Canadians. The weather was miserable, cold and wet. The battlefield was largely below sea level, with only dikes for easy movement; these, naturally, were covered by enemy fire.

Simonds retired to his caravan, thought through the problem and produced his plan. The 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, assisted by the 4th Canadian Armoured and the 52nd British Division, would clear the Scheldt’s south bank—the Breskens Pocket, as it was called. Meanwhile the 2nd Canadian Division would free South Beveland Finally, Walcheren, controlling the Scheldt estuary’s entrance, would be attacked over the causeway joining it to South Beveland and by assault from the sea. Simple, in concept, Simonds had to persuade RAF Bomber Command to attack the dikes that kept the sea away from Walcheren’s fertile soil. Making his case brilliantly against the skeptical air marshals, he won the argument.

The battles were fierce. The Germans in the Breskens Pocket were first-class and well supplied, and it took flamethrowers, relentless artillery fire and much courage to dislodge them from their trenches defending the many canals. The Canadians used their armour, their Buffalo tracked, water-going troop carriers and their mortars to prevail. It took all of October and into November, but First Canadian Army controlled the Scheldt’s south bank.

The going was no easier at South Beveland as the 2nd Division struggled through flooded polders and fought fanatical German paratroops. The Black Watch were cut to pieces on Oct. 13, the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry three days later. Not until Oct. 24 was the isthmus cut, and Beveland was finally liberated. Now it was Walcheren’s turn.

The RAF’s bombing of the dikes began on Oct. 3 and the island quickly flooded, isolating the enemy. British commandos and soldiers, serving under Simonds, attacked from the sea and resistance ceased by Nov. 8. Meanwhile, to divert attention from the seaborne attack, the Canadians had been forced to continue their attack on the heavily defended causeway linking Beveland to Walcheren. Repeated assaults decimated one battalion after another, and the fighting finally ended on Nov. 8. In all, to clear the Scheldt cost 6,367 Canadian killed, wounded and captured, and an equal number of British casualties. But supplies could reach Antwerp, and Nazi Germany’s defeat was now inevitable.

The Scheldt battles mattered. The II Canadian Corps that fought there was entirely made up of volunteers—one million men and women volunteered for service to fight the Axis in the Second World War—demonstrating that Canadians understood what was at stake for their democracy in a war against Hitler’s monstrous regime. The army, untrained, ill-equipped and ill-led in September 1939, had become the best little army in the world, one able to fight and beat the SS and the Wehrmacht. And General Simonds, the sole senior Canadian commander in whom the British and Americans had complete confidence, had demonstrated that he could plan, direct and lead a vital and huge military operation and see his Canadians emerge victorious. Just as in the Great War, the Canadians now knew they could handle the toughest jobs.

Members of The Royal Canadian Regiment head into battle near Chalghowr, Panjwaii, in 2010. [Adam Day]

CANADIAN FORCES HAD NOT FOUGHT IN WAR SINCE THE END OF THE KOREAN WAR IN 1953. They had been under fire on several “peacekeeping” missions, and they had suffered casualties, but war? Combat against a formed enemy force? That did not happen until 2006 in Afghanistan.

The Afghan War that began after al-Qaida’s 9/11, 2001, attack on New York and Washington saw Canada participate in varying ways from 2001 until the withdrawal from combat in 2012. What was certain was that more Canadians served in Afghanistan than in Korea; the number killed in action fortunately fewer in a very different kind of war.

Canada responded quickly to 9/11, dispatching ships, aircraft, Special Forces soldiers and in early 2002, an infantry battalion to Afghanistan and nearby sites. American and allied forces quickly routed al-Qaida, but local Islamist militants, the Taliban, soon re-formed. Canada continued its role, playing a major part in NATO’s International Security Assistance Force in Kabul. By 2006, the focus had shifted to Kandahar, the birthplace of the Taliban, and to the creation of a Provincial Reconstruction Team (PRT) that was to advance reform, to build institutions while the soldiers fought against the Islamists. To protect the PRT, Canada dispatched a battle group from the 1st Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry. The expectation was that the most the estimated 200 Taliban militants in the area could do would be to plant roadside bombs.

This turned out to be completely incorrect. By July 2006, there were thousands of Taliban in the Kandahar region eager to test the Canadians, and the PPCLI found itself facing a well-led, well-equipped force that could move fast. Equipped with effective LAVIII vehicles, the Canadians soon set up Forward Operating Bases, “living among the locals, in the face of the enemy, out of the back of the LAVs.” This meant quicker reaction time, but difficulties in keeping the troops supplied to fight repeated sub-unit actions. The PPCLI’s first major action came in May at the village of Pashmul where Captain Nichola Goddard, an artillery forward observer, was killed. She was the first female Canadian soldier ever to be killed in action.

Two months later, PPCLI fought a major battle in the Panjwaii area where a large Taliban force stood and fought. That was a mistake for the enemy as the Canadians inflicted heavy losses. But in August as the PPCLI prepared to rotate out of theatre and the 1st Battalion of the Royal Canadian Regiment took over, the Taliban repeated their mistake. The Islamists suffered hundreds of casualties, but they killed four Canadians and wounded eleven. The Canadians were astonished to discover that the vacated enemy positions were sophisticated and well-planned. The assault on Pashmul that had threatened Kandahar itself had been defeated at very heavy cost to the enemy.

The fighting went on. The RCR battle group soon faced a major attack on Panjwaii that was shredded by aircraft and artillery and “desperate and unplanned hard-fought actions,” or so one officer described them. Similar smaller attacks continued until the last Canadian combat units returned home at the end of 2011. A training mission remained in Afghanistan until 2014.

If protecting Kandahar was the goal, the Canadian role in Afghanistan might be called a success. But if the aim was to hold the countryside and allow Afghan villagers to lead their lives free of the Taliban, the war has to be judged at best as a partial failure. The Taliban had not disappeared, the Provincial Reconstruction Team’s efforts were limited, and peace and security remained a dream.

But there was another goal for General Rick Hillier, the Chief of the Defence Staff in most of this critical period. Hillier had served in the former Yugoslavia and had been dismayed by the rules and regulations that bound the Canadians there, rules stringent enough that other national troops amended the term “Canbat” for Canadian battalion to “Can’tbat.” That stung, and Hillier vowed to make his soldiers combat capable once more. The Liberal Paul Martin government and the Conservative Stephen Harper government put up the money and equipment, the troops trained hard and adapted to battle quickly, and the Canadian regulars, their ranks bolstered by hitherto-scorned reservists, proved themselves in the field.

The Canadian public was not very supportive of the Afghan war, but they proved to be extremely supportive of the troops. There were “red Fridays” when civilians wore red clothing to show support, bumper stickers and lapel pins. Most striking, every time one of the 158 Canadian soldiers killed in Afghanistan arrived at the air base at Trenton, the cortege en route to Toronto was met by thousands lining the bridges on Highway 401, renamed the Highway of Heroes. Hillier had changed the image of the Canadian Forces from peacekeepers to fighting soldiers, at least temporarily.

In its own way, Afghanistan, much like the Plains of Abraham, the War of 1812, and the two world wars, shaped Canada. The Canadian population was never military minded, but its soldiers in action were skilled and fierce, once they became well-trained and well-equipped. That always took time and money, but fortunately, Canada had allies and, most often, had time to prepare. That might not always be the case, however, and fortunate Canadians should at the very least consider the worst-case scenarios they have often evaded. Time might not always be on Canada’s side.

Advertisement